Education

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson Calls on Nation to Remember Ugly Past Truths

Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson on Friday called on the nation to accept some of the ugliest truths in its history as she confronted the debates roiling the country about racism and violence against Black Americans.

In a speech from the pulpit of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Justice Jackson, the first Black woman to serve on the nation’s highest court, said that she made her first trip to Alabama “to commemorate and mourn, celebrate — and warn.” She was the keynote speaker to mark the 60th anniversary of a bombing by the Ku Klux Klan that killed four young girls at the church as they arrived for Sunday morning service.

“If we’re going to continue to move forward as a nation we cannot allow concerns about discomfort to displace knowledge, truth or history,” Justice Jackson told a crowd of hundreds. “It is certainly the case that parts of this country’s story can be hard to think about. I know that atrocities like the one we’re memorializing today are difficult to remember and relive. But I also know that it is dangerous to forget them.”

“We cannot forget because the uncomfortable lessons are often the ones that teach us the most about ourselves,” she added. “We cannot forget because we cannot learn from past mistakes we do not know exist.”

Justice Jackson’s speech was a rare occasion. The current justices on the court do not often make public appearances, and when they do, it is typically to lecture at law schools or in other academic settings. Although many of the justices have appeared at judicial conferences and spoken at college commencements, only two — Justice Jackson’s predecessor, Justice Stephen Breyer, and Justice Thurgood Marshall, the first Black man to serve on the court — have made notable appearances at civil-rights-related events.

Justice Jackson’s speech at the church was an explicit nod to her own role in history as well as the country’s ongoing battle for racial justice. During her confirmation hearings last year, Republicans who oppose the teaching of slavery and racism as part of the nation’s history frequently questioned her about her support of civil rights.

In her speech, Ms. Jackson acknowledged her “exhausting” journey to the high court, which she said was part of the reason she accepted the invitation to deliver the keynote address at the event.

“I come with the understanding that I did not reach these professional heights on my own, that people of all races, people of courage and conviction cleared the path for me in the wake of the horrible tragedy that snuffed out the brief lives of those four little girls inside this sacred space,” she said. “I’ve come to Alabama with a heart filled with gratitude, for unlike those four little girls, I have lived, entrusted with the sole responsibility of serving our great nation.”

In many respects, Ms. Jackson’s speech was an example of something that always underscored her appointment: Her voice as the first Black female Supreme Court Justice could be as influential as her votes.

The speech comes less than three months after the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action, overturning decades of precedent by declaring race-conscious college admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina unlawful.

Ms. Jackson’s appointment was never expected to change the outcomes of the majority-conservative court, and she recused herself from the Harvard case because of a conflict of interest in serving on governing boards at her alma mater.

But in searing dissents, Ms. Jackson issued a forceful rebuke of the court’s position that America was effectively in a post-racial era. “With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the rip cord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat,” she wrote in her dissent in the University of North Carolina case. “But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.”

In her opposition to the decision, she also took on the court’s only other Black member, Justice Clarence Thomas, a longtime skeptic of affirmative action.

Justice Thomas, speaking from the bench when the decision was announced, said the country had moved past the struggles of the 1950s and ’60s for equal access to education for Black Americans. “This is not 1958 or 1968,” he said. “Today’s youth do not shoulder moral debts of their ancestors.”

In her speech in Birmingham, Justice Jackson spoke of how her parents taught her about the racial violence that occurred in the quest for civil rights, including how Martin Luther King Jr. had sat in a Birmingham jail just months before he eulogized the four little girls at a funeral attended by what the police estimated were 4,000 people, many of them overflowing into the street outside the church’s front door.

“There was a reason that my parents felt it was important to introduce me to those uncomfortable topics and it was not to make me feel like a victim or crush my spirits,” Justice Jackson said. “To the contrary, my parents understood that I had to know those hard truths in order to expand my horizons. They understood that we can only know where we are and where we’re going, if we realize where we’ve been.”

Before Ms. Jackson took the stage, the church bells tolled four times at around 10:22 a.m., marking the minute that the bomb exploded, killing the four girls — Denise McNair, 11, and Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins and Cynthia Wesley, all 14.

“They could have broken barriers. They could have shattered ceilings, they could have grown up to be doctors or lawyers or judges appointed to serve on the highest court in our land,” Justice Jackson said.

In the audience sat Sarah Collins Rudolph, who lost her sister, Addie Mae, her friends and her eye in the bombing. The church also rang two more bells for Johnny Robinson and Virgil Ware, who were killed in an uprising following the bombings.

Just days before the bombing, Gov. George Wallace of Alabama famously said that “white people nowhere in the South wanted integration,” and that what was needed instead were “a few first-class funerals.”

“So yes, learning about our country’s history can be painful, but history is also our best teacher,” Justice Jackson said. “Yes, our past is filled with too much violence, too much hatred, too much prejudice. But can we really say that we are not confronting those same evils now?”

Kitty Bennett contributed research.

Education

Video: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University

new video loaded: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University

transcript

transcript

Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University

House Speaker Mike Johnson delivered brief remarks at Columbia University on Wednesday, demanding White House action and invoking the possibility of bringing in the National Guard to quell the pro-Palestinian protests. Students interrupted his speech with jeers.

-

“A growing number of students have chanted in support of terrorists. They have chased down Jewish students. They have mocked them and reviled them. They have shouted racial epithets. They have screamed at those who bear the Star of David.” [Crowd chanting] “We can’t hear you.” [clapping] We can’t hear you.” “Enjoy your free speech. My message to the students inside the encampment is get — go back to class and stop the nonsense. My intention is to call President Biden after we leave here and share with him what we have seen with our own two eyes and demand that he take action. There is executive authority that would be appropriate. If this is not contained quickly, and if these threats and intimidation are not stopped, there is an appropriate time for the National Guard. We have to bring order to these campuses. We cannot allow this to happen around the country.”

Recent episodes in U.S. & Politics

Education

Video: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

new video loaded: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

transcript

transcript

Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

The police arrested students at a pro-Palestinian protest encampment at Yale University, days after more than 100 student demonstrators were arrested on the campus of Columbia University.

-

Crowd: “Free, free Palestine.” [chanting] “We will not stop, we will not rest. Disclose, divest.” “We will not stop, we will not rest. Disclose, divest.”

Recent episodes in Israel-Hamas War

Education

Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere

In Anchorage, affluent families set off on ski trips and other lengthy vacations, with the assumption that their children can keep up with schoolwork online.

In a working-class pocket of Michigan, school administrators have tried almost everything, including pajama day, to boost student attendance.

And across the country, students with heightened anxiety are opting to stay home rather than face the classroom.

In the four years since the pandemic closed schools, U.S. education has struggled to recover on a number of fronts, from learning loss, to enrollment, to student behavior.

But perhaps no issue has been as stubborn and pervasive as a sharp increase in student absenteeism, a problem that cuts across demographics and has continued long after schools reopened.

Nationally, an estimated 26 percent of public school students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15 percent before the pandemic, according to the most recent data, from 40 states and Washington, D.C., compiled by the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute. Chronic absence is typically defined as missing at least 10 percent of the school year, or about 18 days, for any reason.

Increase in chronic absenteeism, 2019–23

By local child poverty rates

By length of school closures By district racial makeup

Source: Upshot analysis of data from Nat Malkus, American Enterprise Institute. Districts are grouped into highest, middle and lowest third.

The increases have occurred in districts big and small, and across income and race. For districts in wealthier areas, chronic absenteeism rates have about doubled, to 19 percent in the 2022-23 school year from 10 percent before the pandemic, a New York Times analysis of the data found.

Poor communities, which started with elevated rates of student absenteeism, are facing an even bigger crisis: Around 32 percent of students in the poorest districts were chronically absent in the 2022-23 school year, up from 19 percent before the pandemic.

Even districts that reopened quickly during the pandemic, in fall 2020, have seen vast increases.

“The problem got worse for everybody in the same proportional way,” said Nat Malkus, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, who collected and studied the data.

Victoria, Texas reopened schools in August 2020, earlier than many other districts. Even so, student absenteeism in the district has doubled.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

The trends suggest that something fundamental has shifted in American childhood and the culture of school, in ways that may be long lasting. What was once a deeply ingrained habit — wake up, catch the bus, report to class — is now something far more tenuous.

“Our relationship with school became optional,” said Katie Rosanbalm, a psychologist and associate research professor with the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University.

The habit of daily attendance — and many families’ trust — was severed when schools shuttered in spring 2020. Even after schools reopened, things hardly snapped back to normal. Districts offered remote options, required Covid-19 quarantines and relaxed policies around attendance and grading.

Today, student absenteeism is a leading factor hindering the nation’s recovery from pandemic learning losses, educational experts say. Students can’t learn if they aren’t in school. And a rotating cast of absent classmates can negatively affect the achievement of even students who do show up, because teachers must slow down and adjust their approach to keep everyone on track.

“If we don’t address the absenteeism, then all is naught,” said Adam Clark, the superintendent of Mt. Diablo Unified, a socioeconomically and racially diverse district of 29,000 students in Northern California, where he said absenteeism has “exploded” to about 25 percent of students. That’s up from 12 percent before the pandemic.

U.S. students, overall, are not caught up from their pandemic losses. Absenteeism is one key reason.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

Why Students Are Missing School

Schools everywhere are scrambling to improve attendance, but the new calculus among families is complex and multifaceted.

At South Anchorage High School in Anchorage, where students are largely white and middle-to-upper income, some families now go on ski trips during the school year, or take advantage of off-peak travel deals to vacation for two weeks in Hawaii, said Sara Miller, a counselor at the school.

For a smaller number of students at the school who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, the reasons are different, and more intractable. They often have to stay home to care for younger siblings, Ms. Miller said. On days they miss the bus, their parents are busy working or do not have a car to take them to school.

And because teachers are still expected to post class work online, often nothing more than a skeleton version of an assignment, families incorrectly think students are keeping up, Ms. Miller said.

Sara Miller, a counselor at South Anchorage High School for 20 years, now sees more absences from students across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Ash Adams for The New York Times

Across the country, students are staying home when sick, not only with Covid-19, but also with more routine colds and viruses.

And more students are struggling with their mental health, one reason for increased absenteeism in Mason, Ohio, an affluent suburb of Cincinnati, said Tracey Carson, a district spokeswoman. Because many parents can work remotely, their children can also stay home.

For Ashley Cooper, 31, of San Marcos, Texas, the pandemic fractured her trust in an education system that she said left her daughter to learn online, with little support, and then expected her to perform on grade level upon her return. Her daughter, who fell behind in math, has struggled with anxiety ever since, she said.

“There have been days where she’s been absolutely in tears — ‘Can’t do it. Mom, I don’t want to go,’” said Ms. Cooper, who has worked with the nonprofit Communities in Schools to improve her children’s school attendance. But she added, “as a mom, I feel like it’s OK to have a mental health day, to say, ‘I hear you and I listen. You are important.’”

Experts say missing school is both a symptom of pandemic-related challenges, and also a cause. Students who are behind academically may not want to attend, but being absent sets them further back. Anxious students may avoid school, but hiding out can fuel their anxiety.

And schools have also seen a rise in discipline problems since the pandemic, an issue intertwined with absenteeism.

Dr. Rosanbalm, the Duke psychologist, said both absenteeism and behavioral outbursts are examples of the human stress response, now playing out en masse in schools: fight (verbal or physical aggression) or flight (absenteeism).

“If kids are not here, they are not forming relationships,” said Quintin Shepherd, the superintendent in Victoria, Texas.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

Quintin Shepherd, the superintendent in Victoria, Texas, first put his focus on student behavior, which he described as a “fire in the kitchen” after schools reopened in August 2020.

The district, which serves a mostly low-income and Hispanic student body of around 13,000, found success with a one-on-one coaching program that teaches coping strategies to the most disruptive students. In some cases, students went from having 20 classroom outbursts per year to fewer than five, Dr. Shepherd said.

But chronic absenteeism is yet to be conquered. About 30 percent of students are chronically absent this year, roughly double the rate before the pandemic.

Dr. Shepherd, who originally hoped student absenteeism would improve naturally with time, has begun to think that it is, in fact, at the root of many issues.

“If kids are not here, they are not forming relationships,” he said. “If they are not forming relationships, we should expect there will be behavior and discipline issues. If they are not here, they will not be academically learning and they will struggle. If they struggle with their coursework, you can expect violent behaviors.”

Teacher absences have also increased since the pandemic, and student absences mean less certainty about which friends and classmates will be there. That can lead to more absenteeism, said Michael A. Gottfried, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. His research has found that when 10 percent of a student’s classmates are absent on a given day, that student is more likely to be absent the following day.

Absent classmates can have a negative impact on the achievement and attendance of even the students who do show up. Ash Adams for The New York Times

Is This the New Normal?

In many ways, the challenge facing schools is one felt more broadly in American society: Have the cultural shifts from the pandemic become permanent?

In the work force, U.S. employees are still working from home at a rate that has remained largely unchanged since late 2022. Companies have managed to “put the genie back in the bottle” to some extent by requiring a return to office a few days a week, said Nicholas Bloom, an economist at Stanford University who studies remote work. But hybrid office culture, he said, appears here to stay.

Some wonder whether it is time for schools to be more pragmatic.

Lakisha Young, the chief executive of the Oakland REACH, a parent advocacy group that works with low-income families in California, suggested a rigorous online option that students could use in emergencies, such as when a student misses the bus or has to care for a family member. “The goal should be, how do I ensure this kid is educated?” she said.

Relationships with adults at school and other classmates are crucial for attendance.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

In the corporate world, companies have found some success appealing to a sense of social responsibility, where colleagues rely on each other to show up on the agreed-upon days.

A similar dynamic may be at play in schools, where experts say strong relationships are critical for attendance.

There is a sense of: “If I don’t show up, would people even miss the fact that I’m not there?” said Charlene M. Russell-Tucker, the commissioner of education in Connecticut.

In her state, a home visit program has yielded positive results, in part by working with families to address the specific reasons a student is missing school, but also by establishing a relationship with a caring adult. Other efforts — such as sending text messages or postcards to parents informing them of the number of accumulated absences — can also be effective.

Regina Murff has worked to re-establish the daily habit of school attendance for her sons, who are 6 and 12.

Sylvia Jarrus for The New York Times

In Ypsilanti, Mich., outside of Ann Arbor, a home visit helped Regina Murff, 44, feel less alone when she was struggling to get her children to school each morning.

After working at a nursing home during the pandemic, and later losing her sister to Covid-19, she said, there were days she found it difficult to get out of bed. Ms. Murff was also more willing to keep her children home when they were sick, for fear of accidentally spreading the virus.

But after a visit from her school district, and starting therapy herself, she has settled into a new routine. She helps her sons, 6 and 12, set out their outfits at night and she wakes up at 6 a.m. to ensure they get on the bus. If they are sick, she said, she knows to call the absence into school. “I’ve done a huge turnaround in my life,” she said.

But bringing about meaningful change for large numbers of students remains slow, difficult work.

Nationally, about 26 percent of students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15 percent before the pandemic.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

The Ypsilanti school district has tried a bit of everything, said the superintendent, Alena Zachery-Ross. In addition to door knocks, officials are looking for ways to make school more appealing for the district’s 3,800 students, including more than 80 percent who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. They held themed dress-up days — ’70s day, pajama day — and gave away warm clothes after noticing a dip in attendance during winter months.

“We wondered, is it because you don’t have a coat, you don’t have boots?” said Dr. Zachery-Ross.

Still, absenteeism overall remains higher than it was before the pandemic. “We haven’t seen an answer,” she said.

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLarry Webb’s deathbed confession solves 2000 cold case murder of Susan and Natasha Carter, 10, whose remains were found hours after he died

-

Politics1 week ago

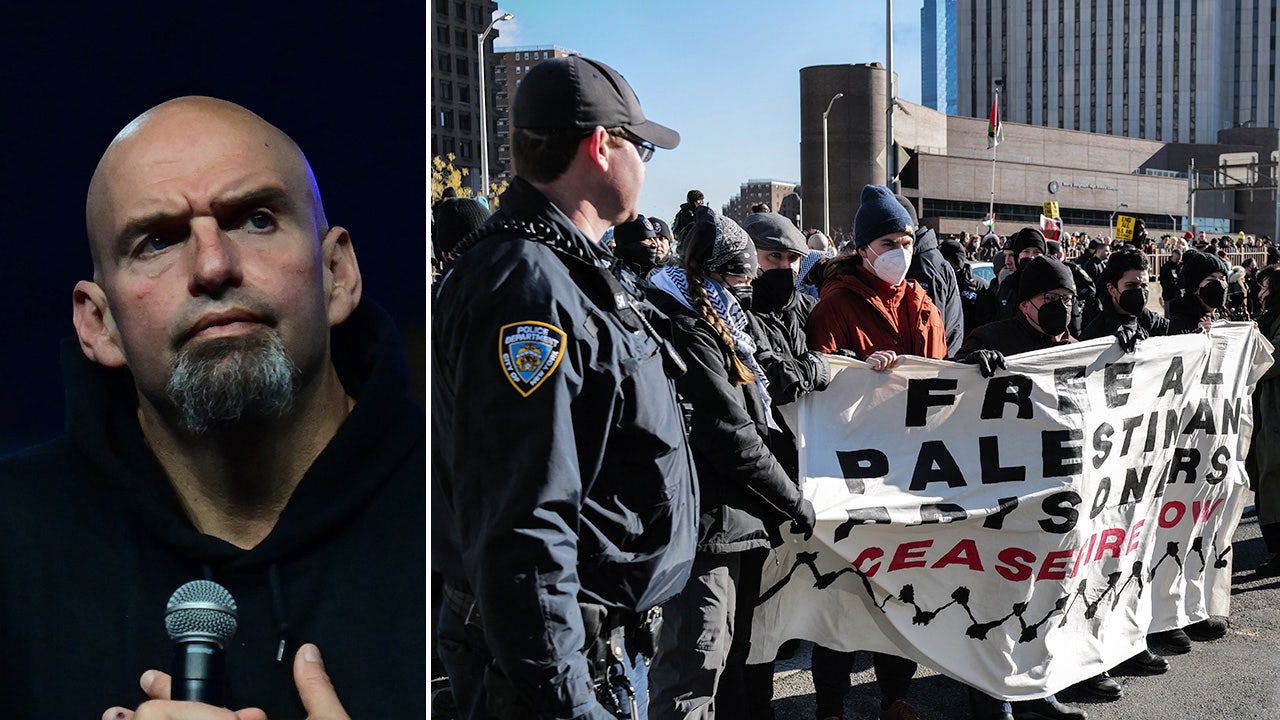

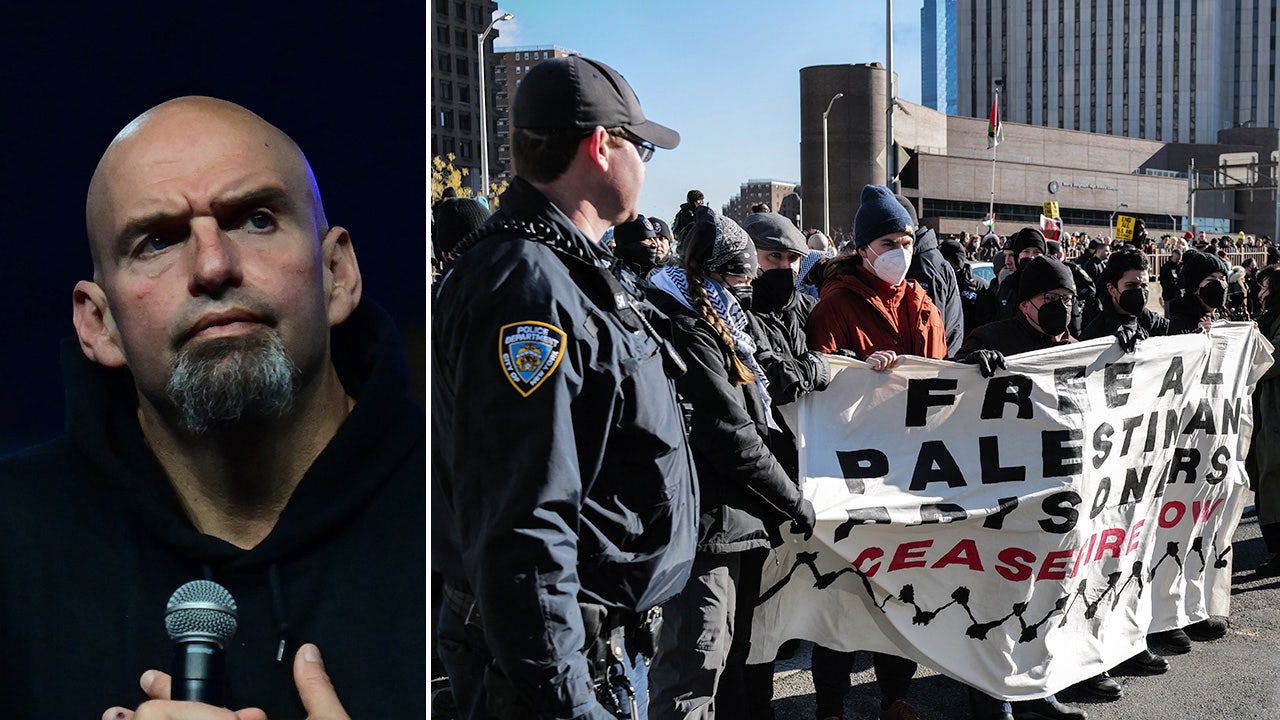

Politics1 week agoFetterman hammers 'a–hole' anti-Israel protesters, slams own party for response to Iranian attack: 'Crazy'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPeriod poverty still a problem within the EU despite tax breaks

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTurkey’s Erdogan meets Iraq PM for talks on water, security and trade