Culture

Challenging Denial With Enduring Images

IT WAS VULGAR AND IT WAS BEAUTIFUL: How AIDS Activists Used Artwork to Battle a Pandemic

By Jack Lowery

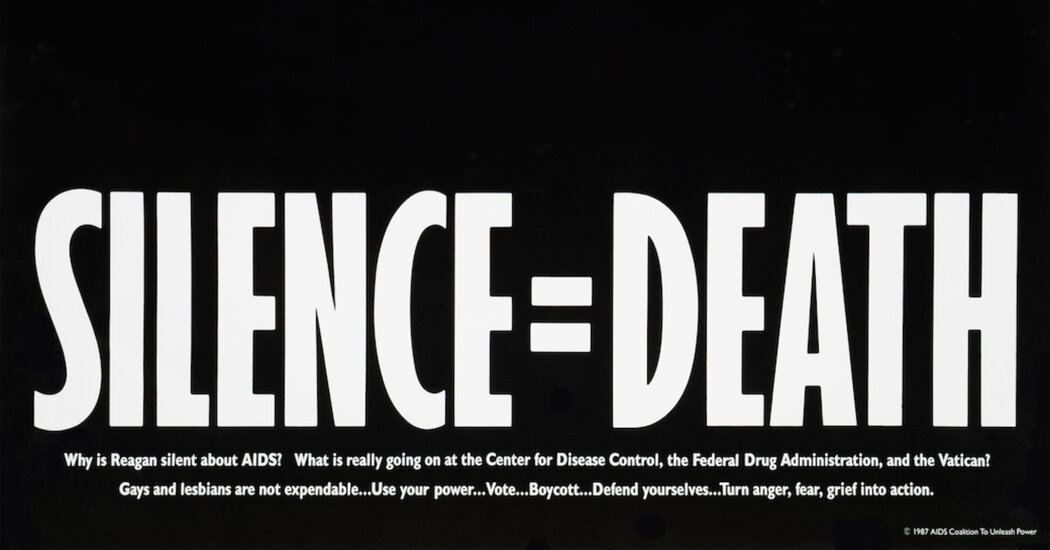

When the AIDS activist motion ACT UP was on the peak of its powers, between 1987 and 1992, daring posters communicated its messages and formed its public picture. In probably the most well-known, a pink triangle swims in a sea of black. The textual content: Silence=Dying.

As Jack Lowery recounts in a considerate, cogent new historical past of their creation, this was the work of six homosexual males who had misplaced individuals to AIDS and began holding potluck dinners to speak about emotions of loneliness and heightened consciousness of mortality. In 1985, AIDS was related within the public thoughts with homosexual males and individuals who injected medicine, and killed just about everybody recognized. America shrugged — or worse. President Reagan’s press secretary shut down questions on AIDS with a joke; William F. Buckley proposed that individuals with AIDS be tattooed on the arms or buttocks.

The creators of Silence=Dying have been impressed by the simplicity of a Vietnam-era antiwar poster. Buckley’s proposal evoked the Holocaust, and one member of the group steered they use the pink triangle that Nazis had compelled homosexuals to put on. He misremembered it as pointing up — a mistake later spun as an intentional sign of empowerment. For the motto, the group compressed a line that one other member, Avram Finkelstein, had written in his journal: “Homosexual silence is deafening.” The poster had two goals: to name on fellow gays to talk out, and to place the remainder of society on discover {that a} new motion had begun.

In February 1987, the poster was wheat-pasted on building websites throughout Manhattan. Shortly after the information reported that an AIDS vaccine was unlikely, the author and activist Larry Kramer known as for a brand new, extra combative political group, which finally turned ACT UP. The creators of Silence=Dying donated the picture to the brand new group, whose members have been quickly carrying it to protests and carrying it in interviews.

The New Museum commissioned a window set up from ACT UP, which precipitated a second artwork collective. On the heart was a charismatic, mercurial man named Mark Simpson, a Texas preacher’s son who had develop into a painter and building employee in New York. He was joined by Finkelstein, a few graphic designers (together with the group’s solely straight girl), an artist, a Rockefeller scion, the supervisor of an AIDS medicine purchaser’s membership (the group’s solely particular person of coloration), the filmmaker Tom Kalin and a cabdriver who turned an AIDS nurse. The group took the title Gran Fury after the artist walked previous patrol automobiles of that mannequin parked exterior a police station.

In Gran Fury’s most iconic poster, from 1988, two clean-cut males in sailors’ uniforms embrace and kiss. Mark Harrington, later one among ACT UP’s leaders in researching medicine, had discovered the black-and-white picture in a movie archive. Within the authentic, the lads’s trousers are unbuttoned, their full glory lolling provocatively within the foreground. Even the cropped picture startled. It evoked Victor Jorgensen’s August 1945 Instances Sq. kiss, but additionally, Lowery explains, “kissing was an integral a part of ACT UP’s tradition,” a means of bridging the moat of concern with which society remoted individuals with AIDS. A sexual cost ran by ACT UP; in response to Kramer, conferences turned “one of the best cruising floor in New York.” The poster’s caption, “Learn My Lips,” was echoed a couple of months later by a campaigning George H.W. Bush, and the irony appeared all of the sharper.

Gran Fury went on to design pretend foreign money that was handed out on Wall Road to protest a pharmaceutical firm’s profiteering; bloody handprints meant to represent the New York Metropolis mayor’s culpable reluctance to behave; and posters for the Venice Biennale that juxtaposed the pope and an erect phallus. The group additionally coined the slogan “Girls don’t get AIDS, they simply die from it” to strain the C.D.C. to replace AIDS’s official definition, permitting girls entry to authorities help.

Some Gran Fury artworks have been duds. Certainly, members of the collective themselves dismissed one practically illegible piece as “the attention chart,” and in Lowery’s telling such put-downs have been widespread. One member in contrast the sniping to that of “The Boys within the Band”; of the group’s eventual demise, one other quipped that “it died as a result of no person wished to be in the identical room anymore.”

The splintering paralleled tensions inside ACT UP, which held collectively for so long as potential two opposite impulses: outrage in opposition to an institution keen to let social outcasts die, and a want to perceive and restore, which required collaboration with the identical institution. In 1991, Harrington led an exodus from ACT UP of members who had develop into consultants within the science and forms of drug analysis and had grown impatient with being informed to not work too intently with authorities — a narrative informed in additional element by each David France and by Sarah Schulman, books with markedly totally different views that recommend that the rift might be recapitulated within the historiography.

Gran Fury’s final nice work grew, in 1993, out of a sequence of political funerals (together with one through which a good friend of mine, David Robinson, threw his companion’s ashes onto the White Home garden) and out of Simpson’s consciousness of his personal imminent loss of life. Modeled on the liturgy of the Passover Seder, the understated graphic work is echo of and reply to the command printed on the backside of the unique Silence=Dying poster: “Flip anger, concern, grief into motion.” As Simpson informed a good friend, earlier than his loss of life, “There’s solely a lot the artwork can do.”

IT WAS VULGAR AND IT WAS BEAUTIFUL: How AIDS Activists Used Artwork to Battle a Pandemic

By Jack Lowery

423 pp. Daring Kind Books. $35.

Caleb Crain is the creator of “Crucial Errors” and “Overthrow.”

Culture

Book Review: ‘How to Be Well,’ by Amy Larocca

HOW TO BE WELL: Navigating Our Self-Care Epidemic, One Dubious Cure at a Time, by Amy Larocca

Oh, the irony of cracking open “How to Be Well” while on vacation in Italy. There, on an island off the coast of Naples, a breakfast buffet included three varieties of tiramisu. Wine was poured not to a stingy fingertip’s depth but from a bottomless carafe — at lunchtime, no less. And when stores closed in observance of an afternoon siesta, the only people on the streets were American tourists, jogging. (I was on the prowl for a postage stamp because, yes, I still send postcards.)

It was from this place of abundance and balance that I followed Amy Larocca, a veteran journalist, into the hellscape of stringent food plans, cultish exercise routines and medical quackery that have, over the past decade or so, constituted healthy living in some of the wealthiest enclaves of the United States. Blame social media, political turmoil or the pandemic — no matter how you slice it, the view is dispiriting. But Larocca’s tour is a lively one, full of information and humor.

The book begins with a colonic, “the flossing of the wellness world,” Larocca writes. We find the author herself on an exam table, “white-knuckled and curled up like a baby shrimp, naked from the waist down.” She recalls her doctor’s disapproval of the procedure — a sort of power washing of the colon — and its risks, including rectal perforation, juxtaposed with one woman’s claim that a colonic made her feel like she could fly, like it was “rinsing out the corners of her psyche.”

Where did we get the idea that the body — specifically a woman’s body — is unclean inside? A problem to be solved? And how did the concept of wellness bloom “like a rash,” Larocca writes, into a $5.6 trillion global industry?

These are the questions she seeks to answer, using data, history, medicine, pop culture and her own experience. She parses fads and trends, clean beauty and athleisure wear, the gospel of SoulCycle and the world according to Goop. She weighs the advantages and disadvantages of micro-dosing and biohacking. She too goes to Italy, where she attends a Global Wellness Summit featuring a spandex and sneaker fashion show and a presentation on ending preventable chronic disease the world over.

At times, Larocca seems to approach her own subject with the same sweep. The second half of “How to Be Well” reads like a survey course, cramming the industry’s relationship to politics, men and the environment into single chapters when each could fill a whole semester. As for why meditation merits more real estate than vaccines, I can only assume that the book was already at the printer when Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was confirmed as health secretary.

But when Larocca goes deep, as she does on self-care, body confidence and sex positivity, she’s at her best — authoritative and witty, personal without being chummy.

She debunks the cockamamie but persistent notion that “feeling old is not an inevitable byproduct of aging but something easily avoided by paying attention.” (And by forking over gobs of cash; more on this shortly.) After attending an Oprah-sponsored conference on menopause, a subject Larocca has covered for The New York Times, she realizes that “aging is different from disease” and “isn’t necessarily something to be cured,” let alone through “neat, tidy, attainable solutions.”

Then there’s the sneaky rebranding of old-school dieting for “detoxification,” another wolf in sheep’s clothing. Think fasting, juicing, abstaining from all manner of verboten foods. Even if the professed endgame is “glow,” Larocca makes clear, “part of the promise is still, always, to rid us of a bit of ourselves.”

And finally, refreshingly, she’s honest about the money at stake for the wellness-industrial complex — not just for stylists turned wellness coaches or models turned nutritionists, but for massive corporations cashing in on an age of worry.

“None of these institutions is nonprofit; none of these institutions is altruistic at its core,” Larocca writes, in a passage reminiscent of Carol Channing’s monologue from “Free to Be You and Me,” in which she reminded us that happy people doing housework on TV tend to be paid actors.

“It is their job to persuade me to come back,” Larocca continues, “to spend more money on what they’ve got to give, to serve their investors, to serve themselves.”

And that, as “How to Be Well” wisely shows us, is the bottom line.

HOW TO BE WELL: Navigating Our Self-Care Epidemic, One Dubious Cure at a Time | By Amy Larocca | Knopf | 291 pp. | $28

Culture

New Crime Novels With Unexpected Twists

By Jeffery Deaver

Colter Shaw is a professional “rewards seeker,” a skilled tracker who specializes in finding missing people — usually for the reward money, though sometimes out of the goodness of his heart. It’s a simple enough vocation and yet, as the suspense veteran Deaver has demonstrated in four prior Shaw novels (and the TV adaptation “Tracker”), the ways in which Shaw finds peril — or peril finds him — keep multiplying. In SOUTH OF NOWHERE (Putnam, 403 pp., $30), his sister Dorion implores him to help to locate potential survivors after a levee collapses in a small Northern California town.

From here, Deaver is off to the proverbial races. Does every chapter have a twist? Pretty much. Is Colter just likable enough to brush off needless conflict and still find time for romance? Definitely. Is the writing a little too reminiscent of detailed outlines like the ones Deaver is known to fashion before writing a first draft? You bet. Could I put the book down? Not a chance.

The Colter Shaw series prioritizes action and the constant possibility of calamity, leaving only the barest amount of room for character development, like Colter’s continued grappling with the effects of his survivalist upbringing. The books don’t measure up to the best of Deaver’s Lincoln Rhyme novels, but they all accomplish their mission: thrilling engagement.

by Uzma Jalaluddin

Kausar Khan, introduced in DETECTIVE AUNTY (Harper Perennial, 326 pp., paperback, $17.99), has spent the past 20 years relishing the stability of placid North Bay, where she and her husband moved after fleeing busy, bustling Toronto in the wake of a family tragedy.

But then her husband dies shortly after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and her daughter, Sana, calls with upsetting news: “I’m in trouble. There’s been a murder, and I’m the prime suspect.” It seems Sana’s landlord has been found inside her clothing store with a dagger in his chest. Kausar returns to Toronto’s Golden Crescent neighborhood as both a concerned mother and a tenacious amateur sleuth.

The case against Sana is strong, but as Kausar discovers, the murder victim had many enemies. If only the ghosts of Kausar’s past would stop haunting her present-day investigation!

Jalaluddin, who has crossed into crime fiction from the romantic comedy genre, doesn’t skimp on plotting — the whodunit twist caught me pleasingly flat-footed — but shines most with character and community, showing the complexities of mother-daughter relationships and the variability of longtime friendships. “Detective Aunty” is the first in a new series and I certainly welcome more installments.

by Michael McGarrity

Reading Michael McGarrity’s noir novel NIGHT IN THE CITY (Norton, 263 pp., $28.99), about the midcentury death of a Manhattan socialite named Laura Neilson, I found it difficult to avoid thinking about Vera Caspary’s 1943 classic suspense novel “Laura” (and the equally classic film adaptation featuring Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews). While I wished for more structural innovation along the lines of what Caspary accomplished, I did enjoy McGarrity’s more conventional narrative here: A man finds his ex-lover murdered and must clear his name, rooting out widespread corruption as the atmosphere thickens.

The man is the assistant district attorney Sam Monroe, who dated Laura for a time and never really got over the way she broke up with him by bringing a new flame to the local bar that was “their private haunt and rendezvous.” So when she summons him to her Manhattan penthouse, off Sam goes, waved in by an expectant doorman — only to find her body, his Army dog tags wrapped around her neck. One thing is clear: He’s been set up. With the help of an intrepid private eye and his former lover’s diary, Sam sets out to find her killer.

McGarrity paints a seedy portrait of a bygone New York that pulses with life, lust and larceny.

by Leonie Swann; translated by Amy Bojang

Finally, it gives me great pleasure that Swann’s exceedingly delightful Sheep Detective books are once again available for American audiences. “Three Bags Full,” first published in 2005 and reissued in February, introduced an intrepid flock on the case of who had killed their beloved shepherd. In BIG BAD WOOL (Soho Crime, 384 pp., $28.95), the sheep — including Zora, “a Blackface sheep with a weakness for the abyss,” Ramesses, a “nervous young ram full of good ideas,” and Miss Maple, “the cleverest sheep in the flock and maybe even the world” — return with a new minder, Rebecca.

They’re wintering next to a French château, which sounds idyllic, but the disappearance of other sheep, the mounting deaths of deer and, eventually, a human, strike fear in the hearts of the flock, who are worried they or their shepherd may be next. Is it a werewolf, the shape-shifting creature called Garou, as the local goats seem to believe? Or a more prosaic yet sinister culprit? How the sheep discover the truth will enchant readers who pay close attention.

Culture

Book Review: ‘Warhol’s Muses,’ by Laurence Leamer

Leamer is undeniably excellent at setting a scene, especially a louche one. He knows just when to have someone wonder if he’s caught crabs from a couch or a crotch. And Leamer is very good on rich people playing at being disheveled, tuned to the comic possibilities of that particular brand of tourism. (Holzer, of Florida real estate wealth, announces after seeing the Stones for the first time that “they’re all from the lower classes. … There is no class anymore. Everyone is equal.” Leamer adds that Holzer’s “maid and butler might have disagreed.”) Nearly every page has at least one great sleazy anecdote or pinch of gossip.

The problem is that so many of these scenes, however expertly set, are variations on the same stale theme of boomers getting up to wild stuff because the times they were a-changin’. Does anyone still need reminding that “the ’60s was a decade of radical political and cultural dissent”? Or that it was once considered shocking that a high-culture figure such as Rudolf Nureyev could go straight from a performance of “Swan Lake” to dancing “to rock ’n’ roll in a nightclub wearing dungarees. Dungarees! Not a suit and tie like some uptight New York businessman”? Reading this book felt akin to being trapped in an endless Time-Life loop of jingle jangle mornings, lazy Sunday afternoons and warm San Franciscan nights, the author providing the stentorian voice-over as the usual footage rolls by: Bob Dylan “would soon emerge as the poetic troubadour of the ’60s”; Brian Jones, “addicted to drugs and sex … was on a short road to an early death”; Jim Morrison, “a troubadour of the counterculture … wrote poetic lyrics that chronicled the lives of his generation.”

Such minor sins might have been forgiven had I ultimately gleaned some deep or unforeseen insight into the lives of the book’s subjects — a group that includes Ultra Violet, Ingrid Superstar, Brigid Berlin and other Factory figures — or, failing that, into Andy Warhol’s work. But I got neither. Nor was I convinced by the whopping claim that “without his Superstars, Warhol might never have become a world-celebrated artist.”

Meeting these 10 historical actors in roughly chronological order as they enter Warhol’s life, one has a view of the artist and his milieu that actually narrows rather than widens. Warhol, a shape-shifter so manic and intense that he could slide into several personas in the span of a single season, is here reduced to a necessarily static figure so that the women can bounce off him. Which is fine as a narrative strategy, but then not much happens to the women, either. As each one flickers into view, her upbringing (often troubled) is dutifully covered before she provides some service to Warhol — as entertainment, as emotional consort, as visual material, as key holder to Park Avenue penthouses — and then fades out to make room for the next one. (Sedgwick is the exception, a frequent and always beguiling presence; Solanas, the would-be assassin, and not one of the 10 Superstars, stands out as foil rather than helpmeet, but appears only briefly.)

Rarely is there any sense of genuine collaboration or exchange. The book’s subtitle gives away the game: In the end, these women of varied backgrounds, with their respective dreams and desires, are all here to play the same passive role — to be inevitably and unsurprisingly “destroyed by the Factory fame machine.”

-

Cleveland, OH1 week ago

Cleveland, OH1 week agoWho is Gregory Moore? Former divorce attorney charged for murder of Aliza Sherman in downtown Cleveland

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoU.S. and China Dig In on Trade War, With No Plans for Formal Talks

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRep. Mikie Sherrill suggests third Trump impeachment as she campaigns to be next New Jersey governor

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump posts AI image of himself as Pope amid Vatican's search for new pontiff

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFamily statement: Rodney Hinton Jr. walked out of body camera footage meeting with CPD prior to officer death

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAre Politicians Too Old? California Democrats Want to Debate an Age Cap.

-

News1 week ago

Stock market today: Dow, S&P 500, Nasdaq futures jump amid jobs report beat, hopes for US-China talks

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘Don’t see a major war with India, but have to be ready’: Pakistan ex-NSA