Business

Jeanette Wagner, Who Globalized the Estée Lauder Brand, Dies at 92

Jeanette Sarkisian Wagner, each a service provider and a diplomat for Estée Lauder, who popularized the model’s high-end lipsticks and perfumes among the many ladies of the Soviet Union and China in the course of the rising globalization and free commerce of the Nineteen Eighties and ’90s, died on Feb. 26 in Manhattan. She was 92.

The loss of life was confirmed by her niece, Nicole Vartanian.

Mrs. Wagner was president of Estée Lauder’s worldwide operations from 1986 to 1998, a interval when the division was remodeled from a small and comparatively unprofitable arm of the New York-based firm to 1 that accounted for roughly half of its multibillion greenback enterprise.

“We had been companions within the creation of Estée Lauder Worldwide,” Leonard Lauder, the corporate’s chief govt in these years, stated in a telephone interview. “We labored collectively hand in glove and we understood one another completely.”

With the Soviet Union’s economic system partly opening beneath its chief Mikhail S. Gorbachev, Estée Lauder launched its first Russian location roughly every week after the autumn of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, beating out McDonald’s by two months. The Moscow department was steps away from the Kremlin and the Purple Sq..

“We’ve what could be the equal of a Fifth Avenue or Madison Avenue handle,” Mrs. Wagner instructed the commerce journal Administration Evaluate in 1990.

On opening day, the police erected barricades and shut down a subway entrance to accommodate a line of a whole bunch of Soviet ladies, a few of them the wives of main figures within the Communist Celebration. They purchased merchandise like Tuscany, a cologne that value 120 rubles — greater than half the common Soviet employee’s month-to-month wage.

Throughout a single day shortly after opening, the shop rang up 210,000 rubles in gross sales.

Ms. Wagner ensured that each girl who stood in line on opening day had the possibility to purchase one thing. She dissuaded Soviet politicians from taking armloads of merchandise for themselves. She helped strike a sophisticated possession cope with the Soviet authorities, and he or she helped oversee the coaching of the shop’s Russian employees, for whom personalised customer support was unfamiliar.

“The entire idea of with the ability to advise and provides individuals experience is totally completely different,” Mrs. Wagner instructed Administration Evaluate. “They haven’t been in a demand-supply state of affairs.”

She was creating a technique for how one can enter a brand new market: set up free-standing shops to manage how the model is launched; nurture private relationships to grasp a brand new market; and overcome limitations to commerce.

She and Mr. Lauder collaborated on one other vital growth within the early Nineteen Nineties — to China. Over the course of her profession, Mrs. Wagner launched advertising campaigns in additional than 100 international locations.

In an sudden reversal, the place the place Mrs. Wagner made one in all her chief worldwide breakthroughs for the corporate is now the location of a significant retreat. Earlier this month, Estée Lauder introduced that it was ceasing all industrial exercise in Russia, together with closing all shops that it owns and operates, in response to the struggle in Ukraine.

“We had been fortunate within the period we had been in,” Mr. Lauder stated, including of Mrs. Wagner, “She was having extra enjoyable that you can ever think about.”

Jeannette Sarkisian was born on July 2, 1929, in Chicago to Souren and Nazely (Norsigian) Sarkisian, refugees from the Armenian genocide. Her household ran two small grocery shops, one in Chicago and the opposite in suburban Evanston.

Jeanette helped out on the shops via her teenage years, and he or she recalled later with pleasure how immaculate they had been saved, with all of the cans rigorously aligned to face in the identical path, and the way her father had instructed her to say no suggestions when she made deliveries that had been marketed as freed from cost.

She graduated with a bachelor’s diploma from Northwestern College, the place she studied English, and within the Nineteen Eighties she went again to highschool, graduating from Harvard Enterprise College’s Superior Administration Program.

Earlier than Estée Lauder, Mrs. Wagner labored in journalism, together with as the primary feminine senior editor of The Saturday Night Publish and because the editor in chief of the Hearst Company’s worldwide magazines.

After stepping down from working Estée Lauder’s worldwide division in 1998, she served as the corporate’s vice chairwoman and on the boards of many nonprofits, together with the Library of America.

Her husband, Paul Wagner, whom she married in 1965, died in 2015. Along with Ms. Vartanian, she is survived by two stepchildren, Paul and Paula Wagner.

Sally Susman, Estée Lauder’s chief of communications throughout Mrs. Wagner’s time as vice chairwoman, recalled in a telephone interview Mrs. Wagner’s extravagant gestures of respect to overseas enterprise companions.

When a delegation of Chinese language authorities officers, a few of whom Mrs. Wagner knew as acquaintances, visited New York on different enterprise and reached out to her as a courtesy, she despatched to every of their resort rooms a bundle with a dinner invitation, Estée Lauder merchandise and vacationer suggestions.

“She was the queen of delivered by hand,” Ms. Susman stated.

Business

Fred Segal failed to compete in the 'very hard beast' of L.A. fashion retail. Here's what went wrong

It was peak 1990s when Cher Horowitz, the fashionable teen queen in the hit film “Clueless,” needed her “most capable-looking outfit” to take her driving test at the DMV.

“Lucy!” she bellowed from her Beverly Hills bedroom, a mound of discarded designer clothes at her feet. “Where’s my white collarless shirt from Fred Segal?”

The beloved Los Angeles boutique retailer got another shoutout in the 2001 rom-com “Legally Blonde”: “Two weeks ago, I saw Cameron Diaz at Fred Segal,” Reese Witherspoon’s Elle Woods said, “and I talked her out of buying this truly heinous angora sweater.”

For more than six decades, Fred Segal was a fixture of L.A.’s retail landscape and a pop culture touchstone. Locals and tourists alike flocked to its ivy-covered walls for upscale but laid-back looks that epitomized effortless Southern California style. It was also one of the city’s most reliable hot spots for A-list celebrity sightings, from the Beatles in the 1960s to, more recently, stars including Britney Spears, Kendall Jenner, David Beckham and Jennifer Aniston.

That all but came to an end Tuesday, when Fred Segal shut its two remaining L.A.-area clothing stores: its West Hollywood flagship on Sunset Boulevard and its Malibu location. (A Fred Segal Home showroom in Culver City remains open.) The retailer — which once had nine locations in California and outposts in Switzerland and Taiwan — blamed the lingering financial effects of the pandemic and the challenges of running a multi-brand company that carried nearly 200 labels.

“Things were really going great until COVID hit,” owner Jeff Lotman, who bought Fred Segal in 2019, told The Times in an interview announcing the closures.

Industry watchers and rivals said the brand’s downfall was the result of several missteps. Once at the forefront of cutting-edge L.A. style, Fred Segal had become stagnant and lacked newness, they said. A lack of product differentiation, stiff competition and the shift to e-commerce also contributed to the chain’s demise.

“One of the challenges for us was that 90% of the brands that we carried were available elsewhere online,” Lotman said in a follow-up conversation Thursday. “Margins became very thin.”

In a city where retail stores flame out quickly, Fred Segal for years was able to stay on top of the latest trends — and set many of them, thanks to its visionary founder.

In 1961, the Chicago-born, Los Angeles-raised Fred Segal opened his first store, a 300-square-foot space on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. Segal had already been embellishing denim with rhinestones, elevating them from everyday closet staples into something one-off and bespoke, and pioneered an in-store “jeans bar,” a concept that would be copied by rivals around the world.

“When Fred Segal the man opened Fred Segal, it was a truly unique place,” Lotman said. “He invented the fashion jean, pop-up shops and experiential shopping. Also he had brands that were not sold anywhere. It was truly one of a kind. He was the original curator of cool.”

In 1965, having outgrown the original space, Segal relocated to the corner of Melrose Avenue and Crescent Heights Boulevard. By buying up other properties in the area, he cobbled together what would eventually be a 29,000-square-foot complex that kick-started the transformation of that stretch of Melrose into the designer-filled destination it is today.

Segal began to experiment with the then-novel shop-in-shop concept, first tapping employees to take charge of different areas within the store, and later recruiting other retail innovators to fill the warren of disparate spaces, making sure each complemented the others.

“They were influencers before there were influencers, before there was social media,” said Nicole Craig, a professor at the Arizona State University Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising. “One of the reasons why they were successful is that they curated a lot of really cool, up-and-coming brands.”

Among them: Kate Spade, Juicy Couture, J Brand and Hard Candy, all fledgling businesses when Fred Segal granted them coveted floor and shelf space.

But in recent years, amid the 2019 ownership change, the pandemic and a challenging retail environment that has led to a rash of store closures for brands big and small, Fred Segal struggled.

“It’s much harder to stand out than it used to be,” Craig said. “That’s where Fred Segal lost its way a little bit. They didn’t have enough of that fresh product that you couldn’t get elsewhere.”

Shelda Hartwell, a vice president at the retail and fashion consultancy Doneger Group, said that although consumers value heritage brands with history and name recognition, Fred Segal needed to do more to keep the excitement going.

“They stayed too much in the sameness for too long,” she said. “You had other retailers that were coming in and opening up their first brick-and-mortar stores that were just offering much more of an experience.”

The experiential aspect is even more important nowadays because so much shopping can be done online, said Mac Hadar, buyer and director of operations for H.Lorenzo, a competing boutique retailer with a store a couple of blocks away from the now-shuttered Fred Segal flagship.

“The retail stores that have continued to do well are the ones that are continuing to push the boundaries and push the limits,” Hadar said. “With the rise of online, you can find almost anything, so you have to have a very original point of view and be pretty daring with what you choose to bring into the store.”

Fraser Ross, owner of Kitson, one of Fred Segal’s biggest rivals, called retail “a very hard beast right now.” Successful brands need to figure out how to evolve quickly, he said.

The Fred Segal store in Santa Monica.

(Fred Segal)

“People aren’t shopping the way they did,” he said. “In the days when you didn’t have Instagram and the web, you could open lots of stores in every neighborhood in L.A. But now, you’ve got to be specific in trying to get the traffic through your door.”

One change that Kitson made is that “we’re not really chasing the hottest brands anymore,” Ross said, because those brands can easily be found online.

Instead, Kitson, which was founded in 2000 and now has four L.A.-area stores, has leaned more heavily into exclusive merchandise and SoCal-inspired products and brands that appeal to tourists, such as Aviator Nation, FreeCity and Sol Angeles. Fred Segal, he said, didn’t embrace that lifestyle aesthetic as much.

Fred Segal also failed to amplify its online presence, which hurt the brand’s relevance, said Ilse Metchek, an industry analyst and former president of the California Fashion Assn. She said the company did a poor job of advertising on social media and through fashion influencers, who now play an outsize role in the industry.

“The idea of legacy brands doesn’t appeal as much anymore,” Metchek said. “You’d rather look at something new that Instagram or TikTok is showing you.”

Lotman, who is chief executive of licensing company Global Icons, bought Fred Segal with ambitious plans to open roughly 20 new shops in major cities around the world and oversee a move into home decor and accessories. Before the pandemic, he had pending deals to open stores in Dubai, Canada and Japan.

Now, the future of the storied brand is unclear.

The Segal family owns the Fred Segal trademark, Lotman said, and any decision about whether to open new stores or begin selling online again would be up to them. Two Fred Segal shops at Resorts World in Las Vegas, which Lotman is not involved with, are still operating.

Larry Russ, the family’s attorney, said this is not the end of the road for the brand but could not share more details.

“We are going to be looking for a new operator to open up more stores in the future,” he said.

Business

The last days of California's oldest Chinese restaurant: From anonymity to history

The conundrum facing the Fong family of Woodland arose earlier this year, shortly after a UC Davis law professor grew interested in a sign posted above the counter that read: “The Chicago Cafe since 1903.”

The Fongs had never given that sign much thought, beyond taking pride in running a family business with a cherished history in the community.

Not Paul Fong, 76, who has worked at the restaurant with his wife, Nancy, 67, since emigrating from Hong Kong in 1973.

Amy Fong has spent plenty of time at the Chicago Cafe in Woodland, Calif. Growing up, she headed to her parents’ restaurant every day after school to do homework and help with chores.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

And not his children, Amy Fong, 47, a physical therapist, and Andy Fong, 45, a software quality engineer at Apple. They grew up sweeping floors and doing homework in the restaurant after school, but had gone off to college (UC Berkeley for Amy; San Jose State for Andy) under strict orders from their parents to find good careers, far from the grind of restaurant work. Now, with children of their own, they were looking forward to their parents’ retirement; they wanted their parents to be able to relax and spend time with their grandchildren.

Then, one day in 2022, Gabriel “Jack” Chin, a law professor at UC Davis, stopped in for lunch. Chin is an expert in immigration law, specifically the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that made it incredibly difficult for Chinese people to immigrate to the U.S. And he knew something the Fongs didn’t, something that would complicate the family’s efforts to wind the business down: If the sign behind the counter was accurate, if the Chicago Cafe truly had been operating since 1903, that would make it a treasure of historic significance.

In January, UC Davis announced the results of Chin’s research: Of the tens of thousands of Chinese restaurants serving food in America, the Fongs’ unsung little diner is the oldest one continuously operating in California, and probably in the U.S. The Fongs suddenly found themselves in possession of an important piece of American history, which had been sitting in plain sight in a farm town 20 miles northwest of Sacramento.

The media rushed to cover the story, and hordes of new customers followed. The Woodland City Council issued a proclamation, which included testimonials from council members about their favorite dishes. And instead of retiring, Paul and Nancy were working twice as hard.

On a recent Friday, their daughter, Amy, came by the restaurant with her two children and took in the scene, in its usual state of friendly chaos. Customers occupied almost every table and banquette, many chowing down the restaurant’s signature chop suey — which, like a lot of food served at the Chicago Cafe, is a Chinese American dish unfamiliar in China itself.

Amy Fong’s daughter, Kira Kranz, entertains herself during a visit to her grandparents’ restaurant.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

The lone waitress, Dianna Oldstad, has worked with the Fongs for decades. She bustled to and fro, greeting regulars with gruff warmth. In the kitchen, Paul and Nancy raced from cutting board to grill with plates of meat and vegetables, and handed the finished dishes off with dizzying speed. Watching over it all were mounted deer and elk and a giant stuffed peacock with its tail unfurled in blue-green glory — gifts from customers over the years.

Paul’s pride in serving his diners, many of whom have become friends and fishing buddies, was evident. Still, his daughter noted with dismay: “They’re getting too old to do this every day.”

The family’s dilemma was so apparent that longtime customers chatted about it as they waited for their food: Would the Chicago Cafe simply end when Paul and Nancy retired? And how could its historic import have emerged just as the Fongs were finally ready to step back?

It is more complicated than one might guess to unearth the history of a Chinese restaurant that has been a fixture in a town for more than 100 years.

In part, that is because of the racism of the early 20th century: Local directories excluded Asian people and businesses until the 1930s, according to Chin. So records of the business had to be found elsewhere.

The Chinese Exclusion Act added another wrinkle. The law sought to prohibit immigration, but didn’t completely stop it. Instead, many Chinese people purchased the identity of Chinese Americans born in the U.S., and then posed as their relatives. The immigrants who came using fake identities were known as “paper sons.”

For a time, restaurants had their own exception to the Chinese Exclusion Act — which some coined “the lo mein loophole” — that allowed business owners to go to China on merchant visas to bring back employees. In the years after 1915, when a federal court added restaurants to the list of businesses allowed such visas, the number of Chinese restaurants in America exploded.

Dianna Olstad, the sole waitress at the Chicago Cafe, has worked with the Fongs for decades.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

Paul Fong’s grandfather almost certainly came before the “lo mein loophole” went into effect. He came as a paper son, steaming into San Francisco Bay under the name Harry Young. The exact year is lost to history: The 1906 earthquake in San Francisco set off a fire that burned up reams of naturalization records — and also allowed many people to add extra “relatives” to the rolls when the records were reconstructed.

“Harry Young” made his way to Woodland, which had developed a busy Chinatown populated by immigrants who had come to work on the transcontinental railroad. At the time, many of Woodland’s neighborhoods were graced by stately Victorians, laid out on large lots shaded by towering oaks. Its Chinatown was a lot less grand: a collection of wood and brick structures built along Dead Cat Alley behind Main Street.

Paul Fong chops food in the solitude of his kitchen at the Chicago Cafe.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

Paul Fong doesn’t know much about how his family came to have a restaurant, and why on earth they called it the Chicago Cafe. He was born in the Taishan area of Guangdong province long after his grandfather had left, and they never met. When Paul was still young, his own father left Taishan to join his grandfather in Woodland; he, too, came as a paper son, under the name Yee Chong Pang.

In 1973, Paul and his mother joined his father at the restaurant, along with Nancy. They would have come earlier, but because his father and grandfather had come as paper sons, there was bureaucracy to cut through even after passage of the Immigration Act of 1965, which finally opened the doors to immigration from Asia.

Paul came to Woodland from Hong Kong, a mega-city that even in 1973 had a population that topped 4 million. Woodland was home to just 20,000. It was a shock.

“In Hong Kong, so many people,” he recalled. The streets were bustling, the nightlife vibrant. The liveliest thing about nightlife in Woodland were the stars: The lack of city lights meant the stars sparkled more brightly.

But Paul grew to love it. Though he spoke limited English, he made friends. Amy recalled that bags of freshly shot duck and truckloads of zucchini would be dropped off periodically at the restaurant door. When a family friend accidentally ran over a peacock, it also wound up at the restaurant — mounted on the wall, not on a plate.

Jerry Shaw has been a regular at the Chicago Cafe for more than four decades.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

Andy said his parents shared little over the years about how the family wound up in Woodland. He recalled going to visit the Woodland cemetery as a child to pay respects to his grandfather and being startled that the etching on the gravestone said “Young” instead of “Fong.” It was the first he’d heard of paper sons.

The Fong children went to the restaurant every afternoon after school. Looking back on their childhood, they could appreciate it was a local institution. Generations of families from all walks of Woodland life came for lunch and special events. At a recent City Council meeting, almost every council member had a personal story, some dating back decades.

“My family grew up eating at the Chicago Cafe,” said Mayor Tania Garcia-Cadena. Councilwoman Vicky Fernandez recalled that her family did too. “Your doors have always been open to all of us,” she said, adding that because her family was Mexican American, that had not always been true of all the restaurants in town.

Nancy Fong gathers ingredients during a crowded lunch service at the Chicago Cafe.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

Still, as proud as they were of their legacy, Paul and Nancy were always clear on one point: Their kids would not be joining the family business. “My dad explicitly told us that he wanted us to go to college. Not do what he was doing, working so hard,” Andy recalled.

When the time came for the couple to retire, the Fong family planned to get out of the restaurant business.

Ten miles down the road, in his office at King Hall on the UC Davis campus, Chin kept thinking about that sign above the counter that said “since 1903.”

Chin grew up in Connecticut and does not speak Chinese. But he was interested in old Chinese restaurants for what they revealed about the history of people of Chinese descent and the legal discrimination they faced for so long.

There are more Chinese restaurants in the United States than there are McDonald’s, and the food they serve is remarkably consistent given much of it would never be served in China.

“A lot of the foods that we think of as Chinese are actually more American and all but unknown in China: General Tso’s chicken, beef with broccoli (broccoli is originally an Italian vegetable), chop suey, egg rolls, fortune cookies. Especially fortune cookies,” journalist Jennifer 8. Lee explained in a 2008 essay about her book, “The Fortune Cookie Chronicles.”

Torin Kranz bides his time in an aged walk-in cooler while his grandparents work the kitchen at the Chicago Cafe.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

This is especially true at the Chicago Cafe, which serves sausage and eggs, pork chops and apple sauce and, on Fridays, clam chowder, along with traditional Chinese American fare such as chop suey and chow mein.

But if these old restaurants don’t reveal much about Chinese food, Chin said, they do reveal a lot about America.

As a law professor, Chin was interested in how elected officials and labor leaders had crafted laws to advance a larger anti-immigration agenda.

In 2018, he and a colleague published a paper called “The War Against Chinese Restaurants,” which laid out the innovative legal efforts — including zoning, licensing and trying to regulate women’s activities — employed in the early 20th century to drive Chinese restaurants out of business.

Researching that paper made him keenly aware of how many Chinese restaurants had operated in America — and how fleeting many of them were. He knew most authorities believed the oldest continuously operating Chinese restaurant was the Pekin Noodle Parlor in Butte, Mont., which dated to 1909 or 1911.

If the Chicago Cafe started in 1903, that made it older.

Chin asked the Fong family whether he could bring in archivists to try to get to the bottom of the mystery? Sure, the family said.

Paul Fong handles business calls during a busy lunch service at the Chicago Cafe.

(Carl Costas / For The Times)

A group descended on the restaurant, digging into dusty cabinets, the attic and the old storage room that included a bed where laborers used to grab naps. They pored over menus, tax receipts and letters. They dove into the archives of the Woodland Daily Democrat and old yearbooks from Woodland High School.

By last spring, Chin and his co-researchers had produced another scholarly paper. “We believe that this is the oldest continually operating Chinese restaurant in the United States,” Chin said of his finding.

The modest storefront on Main Street — with its cash-only policy — suddenly had a new cachet. Tourists came from Sacramento and San Francisco. Locals came flooding back.

“You can’t even get in now,” said Michelle Paschke, a longtime friend whose family used to run a neighboring store. Paschke sat at the packed lunch counter on a recent afternoon, waiting to pay. All around her, other patrons were in the same situation, holding cash out like supplicants while Olstad gestured that she would be there as quickly as she could.

“It’s been a blessing,” Andy said of the overwhelming interest. “At the same time,” he said, “I do want my parents to relax. And somewhat selfishly, I want them to spend time with their grandchildren.”

Back in the kitchen, Paul and Nancy turned out plates with a lightning rhythm, honed over years of practice. “It’s good I guess. It makes me pretty busy,” Paul said of the lunch crowd.

Still, he added, he couldn’t do this forever. “I’m old,” he said, smiling.

But on this day, he was still working, and the orders were piling up. Nancy gestured to a plate of pork ready to be fried. Paul stepped back to the grill.

Business

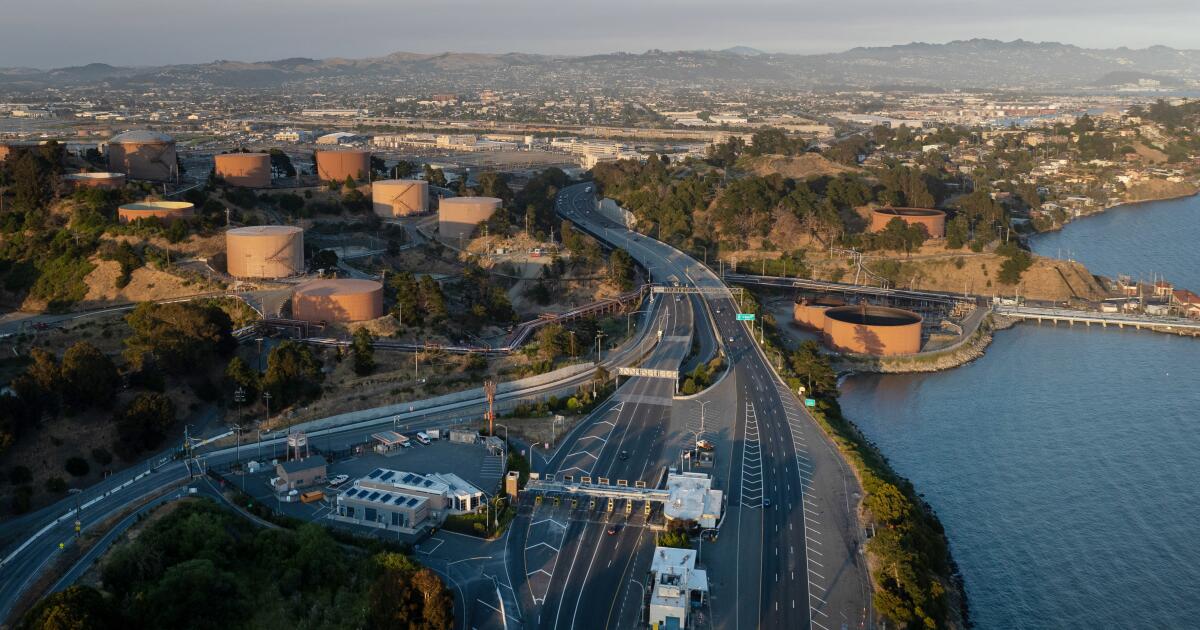

Chevron, after 145 years in California, is relocating to Texas, a milestone in oil's long decline in the state

With the announcement Friday that it was moving its headquarters from California to Texas, Chevron Corp. became perhaps one of the last dinosaurs to slip into the tar pit, a symbol of California’s monumental transition from a manufacturing and production state to the brave new world of services.

In the popular imagination, California has long been seen as Hollywood, sunshine and beaches that attracted millions of new residents and built its sprawling cities. But in reality the great magnet of growth for decades was the production of things: think the aerospace industry, petroleum and agriculture.

The transition away from manufacturing has been going on for decades, exemplified by Silicon Valley, which churns out the ideas for high-tech devices but leaves the actual production to others, overseas, and the sprawling ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which offload the vast flow of manufactured goods from abroad.

Now, it’s Chevron’s turn.

The oil giant was founded in California 145 years ago at the beginning of an era when the state became one of the world’s leading suppliers of oil and its byproducts.

But in recent years, the company has been butting heads with Sacramento over energy and climate policies, which now loom larger than manufacturing in many people’s minds. On Friday, the company said it is moving its headquarters from the Bay Area to Houston.

The move is part of a long, steady exodus of not only Chevron’s operations, but also the larger petroleum industry from California, which in its heyday early last century produced more than one-fifth of the world’s total oil.

While California remains the seventh-largest producer of oil among the 50 states, its production of crude has been sliding since the mid-1980s and is now down to only about 2% of the U.S. total, according to the latest U.S. Energy Information Administration data.

The downshift reflects just how far the state has staked its fortunes away from fossil fuels to renewable forms of energy and, in particular, away from gas-powered cars to become the center of the electric vehicle industry

“Oil and gas has shaped California into what it became, but it has been in a tremendous decline,” said Andreas Michael, an assistant professor of petroleum engineering at the University of North Dakota. Chevron’s move out of the state, he said, “is a milestone in that decline, and it’s very sad to see.”

Sarah Elkind, a San Diego State University history professor who has chronicled the profound impact of oil production on people’s health and industry overall in Los Angeles, wondered out loud whether Chevron was leaving California to get away from regulatory scrutiny.

“It’s unfortunate corporations will relocate their workforces in places that have fewer environmental regulations rather than working in ways that lead to healthy and vibrant communities,” she said.

Chevron, the second-largest U.S. oil company, based in San Ramon, didn’t respond to interview requests Friday. In a statement, the company said that the move to Texas would allow the company to “co-locate with other senior leaders and enable better collaboration and engagement with executives, employees, and business partners.”

Chevron has been steadily shrinking its footprint in the Bay Area. It moved Chevron Energy Technology, a subsidiary, to Texas last decade, and two years ago the company sold its San Ramon campus as it began shifting jobs to Houston. The company already has about 7,000 employees in the Houston area.

Chevron has some 2,000 employees in San Ramon. It is the latest high-profile departure of a California company to another state.

Recently Elon Musk said he is moving his companies SpaceX and X from California to Texas, and over the last decade there have been scores of other California companies in tech and other industries that have fled the state, with many attributing it to the state’s high operating costs and other policies that they see as not supportive of business.

Last fall, California’s attorney general sued Chevron and several other big oil companies, alleging that their production and refining operations have caused billions of dollars in damage and that they deceived the public about the risks of fossil fuels in global warming.

Chevron’s chief executive, Mike Wirth, has pushed back against the suit and California’s approach to climate change, saying that planet warming is a global issue and that piecemeal legal actions aren’t helpful.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office downplayed the significance of Chevron’s relocation news Friday and highlighted the growth and opportunities in clean energy for California, which it said already has six times more jobs than fossil fuels employment.

“This announcement is the logical culmination of a long process that has repeatedly been foreshadowed by Chevron,” said Alex Stack, a spokesman for the governor’s office. “We’re proud of California’s place as the leading creator of clean energy jobs — a critical part of our diverse, innovative and vibrant economy.”

Wirth and Chevron’s vice chairman, Mark Nelson, will move to Houston before year’s end. “There will be minimal immediate relocation impacts to other employees currently based in San Ramon,” Chevron said in its statement.

Some operations will remain in San Ramon — along with “hundreds of employees,” Wirth told CNBC on Friday — but the company said it expects all corporate functions to move to Houston over the next five years.

“We’ve got a proud history in California,” Wirth said, noting that the company began in 1879 in the Pico Canyon oil field just west of Newhall, the site of the state’s first huge flow of oil three years earlier. But he said Houston is the industry’s epicenter and where Chevron’s suppliers, vendors and other key partners are located.

Chevron started out as Pacific Coast Oil Co., incorporated in 1879 in San Francisco, and later was long known as Standard Oil of California. With other companies, it rode the drilling boom in Los Angeles in the early 1900s when big oil fields were discovered in places like Long Beach and Santa Fe Springs, spurring the region’s industrial development but also creating increasing concerns about its impact on especially working-class neighborhoods, with uncontrolled gushers, fires, oil spreads and loud diesel pumps, said Elkind. In the 1920s, a full 20% of the oil produced in the U.S. came from Los Angeles County.

California’s relationship with the oil and gas business survived well into the 1960s. But at the end of that decade the Santa Barbara oil spill helped spur a huge environmental movement, said Michael, the University of North Dakota petroleum expert. With the state’s aggressive pursuit of zero-carbon policies, production of crude has fallen to less than 300,000 barrels a day, about one-fourth of what it was in mid-1980s.

“And I don’t think we’ve hit bottom yet,” said Uduak-Joe Ntuk, an industry expert who until this year oversaw oil fields for the California Department of Conservation’s energy management division. Los Angeles County alone still has thousands of oil wells. “We have billions of barrels of recoverable oil in California, but they’re just in the ground.”

-

Mississippi4 days ago

Mississippi4 days agoMSU, Mississippi Academy of Sciences host summer symposium, USDA’s Tucker honored with Presidential Award

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTyphoon Gaemi barrels towards China’s Fujian after sinking ship off Taiwan

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Biden Says It’s Time to ‘Pass the Torch’ to a New Generation

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoRepublicans say Schumer must act on voter proof of citizenship bill if Democrat 'really cares about democracy'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Kamala Harris May Bring Out Trump’s Harshest Instincts

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWho Can Achieve the American Dream? Race Matters Less Than It Used To.

-

World6 days ago

More right wing with fewer women – a new Parliament compendium

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse unanimously votes to create Trump assassination attempt commission