Business

Column: The FTC is right about Amazon’s monopolistic practices, but struggles with what to do about them

Few Amazon customers or sellers could be surprised by most of the allegations in the massive lawsuit filed against the company Tuesday by the Federal Trade Commission and 17 states.

The lawsuit accuses Amazon of a host of anti-competitive practices, all aimed at exploiting its enormous footprint in the online retail market.

These include price manipulation and punitive and coercive behavior against sellers with the temerity to use competing retail platforms or to set their own prices or engage in non-Amazon methods to serve their own customers.

The harms here…have basically created a really distorted and competitive landscape….That may require significant relief.

— FTC Chair Lina Khan, contemplating an Amazon breakup

Then there’s the degradation of the Amazon shopping experience by the infusion of “sponsored” — that is, favored — products that may be inferior or more expensive than those a buyer may be seeking.

The company’s public response to the lawsuit is that it would result in “fewer products to choose from, higher prices, slower deliveries for consumers, and reduced options for small businesses,” its general counsel, David Zapolsky, said in a prepared statement, adding that the agency is “wrong on the facts and the law.”

But most of the FTC’s allegations are familiar enough. Consumers know how hard it is to determine whether Amazon’s prices are the lowest available. They know that when they’re searching for an item on Amazon.com, the varieties pushed at them most assiduously are those from Amazon’s commercial partners or marketed by Amazon itself.

They feel the pressure to sign up for Amazon’s Prime service, now $139 a year, necessary to receive one- or two-day, or even overnight, delivery, in addition to the company’s video and music streaming services.

Sellers who have marketed their merchandise on Amazon are certainly aware of the cost — a share of as much as 50% taken by the company.

They know the consequences of flouting its rules or trying to discount its products from Amazon’s price, which include banishment from the website’s one-click “buy box” or the burying of discounting sellers “so far down in Amazon’s search results that they become effectively invisible,” to quote the lawsuit.

The question is what to do about it.

That’s the question implicit in every one of the FTC complaint’s 174 pages. It’s the same question raised any time the government tries to rein in a big, powerful corporation, but it’s especially important in this case, because there are so very few corporations that dominate their markets so powerfully.

The FTC points to Amazon’s ability to leverage its various businesses, which include its “fulfillment” services — the warehousing, packing and shipping of sellers’ merchandise — and Prime eligibility, which gives sellers’ products preferential placement on the website and by eliminating shipping charges lowers the cost of their products for buyers.

That suggests that one answer would be to break up Amazon, say by forcing it to divest its fulfillment operation. FTC Chair Lina Khan dodged that issue in her statements about the lawsuit, possibly because she knows that the remedy to Amazon’s misdeeds, assuming it’s found guilty, would be in the hands of a federal judge.

“At this stage, the focus is more on liability,” she told reporters in a briefing session Tuesday. On Wednesday, during an appearance at a Washington, D.C., conference sponsored by Politico, she noted that in the lawsuit “we don’t specify any one type of remedy.”

She also observed, however, that “the harms here are really mutually reinforcing, and have basically created a really distorted and competitive landscape … that may require significant relief.”

The lawsuit isn’t entirely silent on possible remedies, mentioning, among other options, “structural relief.” That could only mean a breakup.

Some disclosures are proper here. I am, like many other customers, a willing prisoner of the Amazon ecosystem, or perhaps more accurately, an addict. The books I read for pleasure are almost invariably ebooks, which means they’re Amazon ebooks; I blindly buy the latest version of the company’s Kindle e-reader (up to and including its new large-format Kindle Scribe).

If I’m interested in a book that doesn’t come in a Kindle version, I’ll wait until it does. I can’t remember the last time I bought an ebook not on Amazon. All but two of the books I’ve written come in Kindle versions, for which I’m thankful.

Outside of food and gasoline, I probably do 70% to 80% of my shopping online, and the vast majority of purchases are on Amazon. I’ll make a purchase on Amazon even if the product is available at a store less than a mile away, and especially if it will be delivered the next day or even (increasingly) overnight.

That doesn’t mean that I’m an uncritical fan. I’ve had to train myself to look past the “sponsored” products Amazon thrusts at me when I’m searching for a product. I’ve avoided its Echo/Alexa devices, because I know they exist to push favored products my way, and who wants a device in the home with the capability of listening in to private conversations?

I’m not happy that I can’t own an ebook purchased on Amazon, but only purchase a license giving me the right to read it (but not give it away, like a physical book). Nor that this arrangement gives Amazon rights over my ebook library that I may not even know about, as when it stealthily deleted from customers’ Kindles versions of George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and “1984” after copyright issues arose with those versions.

An Amazon ebook generally can be read only on an Amazon Kindle or an Amazon app — another pair of mutually reinforcing near-monopolies.

Quite obviously, Amazon could never get away with such restrictive rules if it had genuine competition in the ebook or e-reader markets.

Amazon and its mouthpieces in Congress have made much of the fact that Khan has had Amazon’s number for years. Exhibit A is her 2017 article in the Yale Law Review titled “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.” Amazon and Meta (then Facebook) tried to use it to force Khan to recuse herself from FTC proceedings against them. Wisely and properly, she turned them down.

The article delved deeply into Amazon’s anti-competitive strategies, which consisted chiefly in undercutting competitors’ prices and consequently taking losses; the company’s expectation that this would drive rivals out of its markets and leave the field clear for it to turn to extracting profits from consumers by exploiting its near-monopoly bore fruit in the long term.

Khan homed in on, among other tools, Amazon’s fulfillment services. But she noticed how Amazon leveraged its Prime membership by bundling “other deals and perks” into it, turning Prime into its “biggest driver of growth.”

The discussions in the FTC lawsuit of Prime and fulfillment as anti-competitive tools replicate Khan’s 2017 analysis with astonishing fidelity, showing that Khan understood Amazon’s business strategy very well indeed.

The remedies Khan offered in 2017 wouldn’t be adequate to rein in the Amazon of today. She recommended applying especially close scrutiny to merger deals reached by companies that already dominated their markets — but that might not work with a company such as Amazon, which has the ability to expand its market dominance without having to acquire other companies.

What most people overlook is that the 2017 article was a critique not so much of Amazon, but of the failure of antitrust regulators to recognize that the new online retail market was fundamentally different from bricks-and-mortar retailing, and that Amazon had been able to exploit that failure.

The best example, Khan pointed out, involved the efforts by major book publishers to counteract Amazon’s policy, rolled out in 2007, of pricing bestseller ebooks at $9.99, undercutting the publishers’ hardcover and ebook prices. Within two years, Amazon’s share of the ebook market was 90%.

The publishers struck a deal with Apple allowing them to set their own ebook prices for sale on Apple’s iBooks app. Amazingly, the Justice Department sued Apple and the publishers for colluding to fix prices. As Khan noted, the DOJ found “persuasive evidence lacking” that Amazon had engaged in predatory pricing.

Apple eventually settled the lawsuit for $450 million, the three largest publishers — Hachette Book Group, Simon & Schuster, and HarperCollins — settled for a combined $69 million, and the last two, Macmillan and Penguin, settled by agreeing not to set ebook prices. Apple never became a significant player in the ebook market.

As Khan perceived, old-school antitrust regulators failed to understand how the retail market had evolved and Amazon was poised to take advantage: “How steep discounting on a platform … creates a higher risk that the firm will generate monopoly power” than discounting in physical stores, and how Amazon’s business had become so big and varied that it could undercut rivals’ prices, take a temporary loss, and recoup its red ink in multiple ways.

The lawsuit that her FTC filed against Amazon sends a clear signal: She doesn’t intend to make the same mistake.

Business

South Korea struggles with uncertainty over U.S. trade negotiations

SEOUL — As the Trump administration has been churning out trade threats this week, South Korea, a crucial trading partner and military ally, has been struggling — like many — to navigate the uncertainty that looms over trade negotiations with Washington.

On Monday, Trump sent a letter dictating new tariff rates to 14 countries including South Korea, which was hit with a 25% tax. The levies were set to kick in Tuesday, but were postponed to Aug. 1. Trump left the door open for another extension, telling reporters the new deadline was “firm but not 100% firm,” depending on what trade partners could offer.

But it’s unclear whether the additional three weeks will be enough to resolve the longstanding disagreements between Washington and Seoul. One of the biggest points of contention is South Korea’s auto industry, which was the third biggest exporter of automobiles to the U.S. last year.

Although White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said Monday that Trump’s phone was ringing “off the hook from world leaders all the time who are begging him to come to a deal,” the tone in Seoul has been reserved.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, left, walks across the tarmac on Sunday as President Trump boards Air Force One. On Monday, Trump dictated new tariff rates to 14 countries, including a 25% tax on South Korea.

(Jacquelyn Martin / Associated Press)

Last week, ahead of the initial July 8 deadline, South Korean President Lee Jae Myung, who took office last month, said “it’s difficult to say for certain that we can finish [the trade talks] by July 8.”

“Both sides are doing their best and we need to come up with an outcome that can be mutually beneficial to both parties, but we still have not yet been able to clearly establish what each party wants,” he added.

Since then, senior South Korean trade officials have been dispatched to Washington with the hopes of bringing a deal within striking distance.

“It’s time to speed up the negotiations and find a landing zone,” Trade Minister Yeo Han-koo said after meeting with U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick on Monday.

So far, the only two countries that have struck new trade deals with the Trump administration are the U.K. and Vietnam.

But the Lee administration has maintained a note of caution. At a high-level meeting held Tuesday to discuss the current state of the negotiations, Lee’s presidential chief of staff for policy, Kim Yong-beom, reportedly emphasized the “national interest” over speedy dealmaking, instructing officials to support tariff-affected industries and “diversify” South Korea’s export markets.

Under a decades-long free trade agreement, South Korean tariffs on most U.S. goods are already zero, meaning there are fewer concessions Seoul can offer, analysts say. And on the key points of contention such as automobiles, there is little daylight to be found.

“This announcement will send a chilling message to others,” Wendy Cutler, vice president of the Washington-based Asia Society Policy Institute and former deputy U.S. trade negotiator, said in a post on X.

Trump’s letter also suggested that the U.S. will “not be open to reprieves” from sectoral tariffs, including those on automobiles, Cutler added.

South Korean trade officials have stressed that removing or significantly reducing the 25% tariffs on cars is a top priority.

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt holds a trade letter sent by the White House to South Korea during a news conference on Monday.

(Al Drago / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

But South Korean cars from Hyundai and Kia factor significantly into the $66-billion trade deficit that Trump has decried as unfair. Last year, South Korea was the third biggest exporter of automobiles to the United States, to the tune of $34.7 billion. It bought $2.1 billion worth of cars from the U.S.

Until now, the country’s flagship automakers Hyundai and Kia have been able to sidestep any major tariff shocks, achieving instead record sales in the first half of the year by selling existing inventory in the U.S.

But many believe it is only a matter of time until they will have to raise vehicle sticker prices, as some competitors have done. Both companies’ operating profits are now forecasted to hit double-digit declines compared with the previous year.

The U.S. has also reportedly demanded concessions that touch on sensitive issues of food or national security in South Korea — a far harder sell to the public than the expanded manufacturing cooperation that South Korea has sought to center in the trade talks.

Among these are opening up South Korea’s rice market to U.S. imports and allowing Google to export high-precision geographic data to its servers outside of South Korea.

As an essential crop that represents a significant portion of farmers’ incomes, rice is one of the few heavily protected goods in South Korea’s trade relationships. Under its free trade agreement with the United States, Seoul imposes a 5% tariff on U.S. rice up to 132,304 tons, and 513% for anything after that.

U.S. Army soldiers attend a ceremony last month in Dongducheon, South Korea. A 2021 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that it cost $19.2 billion to maintain American troops in South Korea from 2016 through 2019.

(Kim Jae-Hwan / SOPA Images via Getty Images)

The South Korean government has long denied Google’s requests to export high-precision geographic data — which is used for the company’s map services — on the grounds that it could reveal sensitive military sites that are essential for defense against North Korea. Last year, Ukraine accused Google of exposing the locations of some of its military systems to Russia.

Equally vexing are Trump’s long-running demands that Seoul should pay more to host the some 28,500 U.S. troops stationed in South Korea.

“South Korea is making a lot of money, and they’re very good. They’re very good, but, you know, they should be paying for their own military,” Trump said at a White House Cabinet meeting on Tuesday, adding that he told South Korea it should pay $10 billion a year.

Over a four-year period from 2016 through 2019, the total cost of maintaining U.S. troops in South Korea was $19.2 billion, or around $4.8 billion a year, according to a 2021 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. Over that period, South Korea footed about 30% of the total annual costs, in addition to providing indirect financial support such as waived taxes or foregone rents.

Under the Special Measures Agreement, the joint framework that governs this arrangement, Seoul’s payments have grown over time. Under the latest version, which covers 2026 to 2030, Seoul’s annual contribution beginning next year will be $1.19 billion, an 8.3% increase from 2025, and will increase yearly thereafter.

Trump’s demand for nearly 10 times that — along with the threats that the U.S. might pull its troops from the country — has previously drawn widespread outrage in the country, spurring calls by some for the development of South Korea’s own nuclear arsenal.

“The Special Measures Agreement (SMA) guarantees stable conditions for U.S. troops stationed in Korea and strengthens the joint South Korea – U.S. defense posture,” a spokesperson for South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in response to Trump’s comments.

“Our stance is that the South Korean government will adhere to the 12th SMA, which was agreed upon and implemented in a legitimate manner.”

Business

Commentary: Does America need billionaires? Billionaires say 'Yes!'

What’s the most downtrodden and persecuted minority in America?

If you said it’s transgender youths, immigrant workers or women trying to access their reproductive health rights, you’re on the wrong track.

The correct answer, judging from a surge in news reporting over the last couple of weeks, is the American billionaire.

I don’t think that we should have billionaires because, frankly, it is so much money in a moment of so much inequality, and ultimately, what we need more of is equality across our city and across our state and across our country.

— Zohran Mamdani, candidate for NYC mayor

Concern about the welfare of this beleaguered minority (there are about 2,000 billionaires in the U.S.) has been triggered — or re-triggered — by the victory of Zohran Mamdani in New York City’s June 24 Democratic primary.

A self-described “democratic socialist,” Mamdani has had to weather bizarrely focused questions from cable news anchors and others about comments he has made about extreme wealth inequality in the U.S., and specifically in New York.

“I don’t think that we should have billionaires,” he told Kristen Welker of NBC’s “Meet the Press” on June 29.

Welker had asked Mamdani, “Do you think that billionaires have a right to exist?” This was a weirdly tendentious way of putting the question. She made it sound as though he advocated lining billionaires up against a wall and shooting them. In fact, what he has said is that the proliferation of billionaires in America, and the unrelenting growth in their fortunes over the last decades, signified a broken economic system.

Nevertheless, the billionaire class and their advocates in the media and on cable news expressed shock and dismay at the very idea. “It takes people who are wealthy in New York to maintain the museums, maintain the hospitals,” John Catsimatidis, a billionaire real estate and supermarket tycoon, fulminated on Fox News. “Do you know how much money we put up to contribute toward museums and hospitals and everything?”

Catsimatidis may not have realized that he had proved Mamdani’s case: In New York and around the country, a tax structure that indulges the 1% with tax breaks has forced austerity on museums and hospitals and services that should be publicly supported. They’re public goods, and they shouldn’t be dependent on the kindness of random plutocrats.

The sheer scale of billionaire wealth in the U.S. prevents most people from understanding how historically outsized it is. “To own $1 billion is to possess more dollars than you’ll ever count,” observed Timothy Noah of the New Republic in a must-read takedown of the American oligarchy published last month. “It’s to possess more dollars than any human being will ever count. And that’s just one billion. Forbes counts 15 Americans who possess hundreds of billions.”

The most comprehensive defense of billionaires appeared July 1 in the Financial Times. It was written by Michael Strain, director of economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a pro-business think tank that has advocated against increasing the minimum wage (in a article by Strain), against the Dodd-Frank post-Great Recession banking reforms, against environmental legislation and against tobacco regulations, among other bete noires of the right.

“We should want more billionaires, not fewer,” Strain writes. “While amassing their fortunes, billionaires make the rest of us richer, not poorer.”

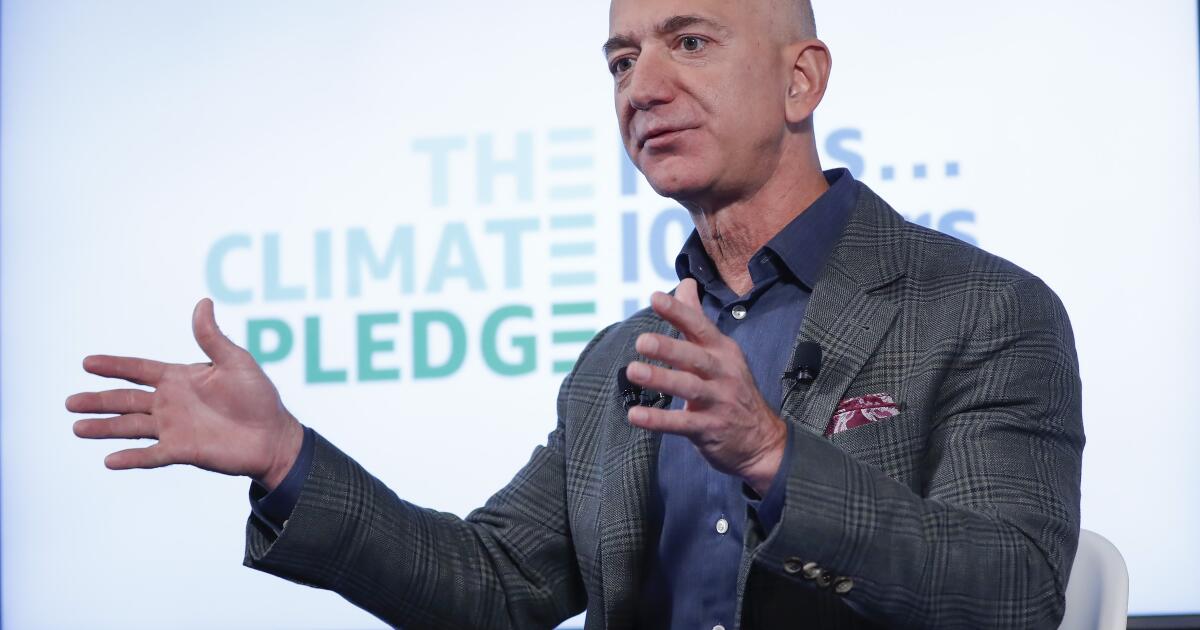

Exhibit A on Strain’s docket is Jeff Bezos, the Amazon.com magnate whose recent wedding in Venice is estimated to have cost as much as $25 million, tasteful and unassuming as we all know it to have been.

Strain cites the common estimate of Bezos’ personal fortune at about $240 billion. He then applies a calculation developed by Nobel economics laureate William D. Nordhaus in 2004, that only 2.2% of the social value of innovations is captured by the original innovators. If Bezos’ $240 billion is 2.2% of the social value of Amazon’s revolution in retailing, then Bezos must have created $11 trillion in wealth for the rest of us.

“Not a bad deal,” Strain writes.

Strain’s interpretation of Nordhaus is hopelessly half-baked. First, Nordhaus was talking about the gains captured by corporations, not individual entrepreneurs. Also, his estimate arose from abstruse economic formulas and lots of magic asterisks.

Nordhaus didn’t present his findings as a defense of any particular economic policies — the 2.2%, he wrote, was excess or “Schumpeterian” profits, those exceeding what would be expected from the normal return from invested capital, which implies that they’re somewhat illegitimate.

Further, it makes no sense to start with an individual entrepreneur’s wealth and extrapolate it to the social value of his or her innovation. It would be more appropriate to try to estimate the social value of the innovation, and then ask whether the innovator’s profits are too much, not enough, or just right.

I asked Strain to justify his treatment, but didn’t hear back.

Another issue with Strain’s advocacy is that he depicted every innovation as the product of a single person’s efforts. Elsewhere in his op-ed, he wrote that Bill Gates and Michael Dell “have made hundreds of millions of workers more productive by creating better software and computers, driving up their wages.”

He also cited Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who “revolutionized email, internet search and mapping technology”; he added that “many of us would eagerly shell out money every month for these services, if they weren’t provided by Google free of charge.”

(Is that so? If Google thought that consumers would eagerly pay for its services, you can be sure the company would find a way to charge for them, instead of making its money from advertising and sponsorship deals.)

This isn’t the first time that billionaires have felt abused by the zeitgeist. Back in 2021, I wrote that America plainly leads the world in its production of whining billionaires. My example then was Leon Cooperman, a former hedge fund operator who appeared on Bloomberg to grouse about proposals for a wealth tax. He called them “all baloney,” though a viewing of the broadcast suggested he was about to use another label beginning with “B” and caught himself just in time.

A few years earlier, in a ghastly letter published in the Wall Street Journal, Silicon Valley venture investor Thomas Perkins compared the suffering he and his colleagues in the plutocracy had experienced due to public criticism to that of Jews facing Nazi pogroms. “I would call attention to the parallels of fascist Nazi Germany to its war on its ‘one percent,’ namely its Jews, to the progressive war on the American one percent, namely the ‘rich,’” Perkins wrote.

The truth, of course, is that while rich entrepreneurs love to pose as one-man bands, every one of them acquired their wealth with the help and labor of thousands of others. Many of the rank-and-file workers without whom Bezos, Dell and their fellow plutocrats could have reached their pinnacles of fortune have struggled in the oligarchic economy, relying on public assistance to make ends meet.

Bill Gates didn’t originally create “better software” — Microsoft’s original product was a computer operating system he sold to IBM, but which was developed by someone else, Gary Kildall. As of last year, Microsoft employed more than 220,000 people. Dell’s original innovation wasn’t a better PC, but a system of selling clones of IBM PCs by mail order.

It’s proper to question whether any of these innovations have been unalloyed social boons. Amazon may have revolutionized retail, but at the cost of driving untold mom-and-pop stores, and even some big chains, out of business, and paying its frontline workers less than they’re worth.

As for its benefits for consumers, in a lawsuit filed in 2022, California accused Amazon of hobbling retail market competition by having “coerced and induced its third-party sellers and wholesale suppliers to enter into anticompetitive agreements on price.”

The state said that “Amazon makes consumers think they are getting the lowest prices possible, when in fact, they cannot get the low prices that would prevail in a freely competitive market.” (Emphasis in the original.)

Amazon says the state’s claims are “entirely false and misguided,” and denies the state’s assertion that its agreements with vendors and suppliers are designed to “prevent competition” or “harm consumers.” The case is scheduled to go to trial in San Francisco state court in October 2026.

That brings us back to Mamdani. In questioning whether billionaires should exist in the U.S., he was implicitly repeating an observation favored by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.): “Every billionaire is a policy failure,” a phrase generally attributed to AOC adviser Dan Riffle.

Riffle’s point is that the accumulation of such wealth reflects policies that exacerbate economic inequality such as tax breaks steered toward the richest of the rich, leading to the impoverishment of public services and programs. That trend has been turbocharged by the budget bill President Trump signed on July 4, which slashes government programs to preserve tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy enacted in 2017 by a Republican Congress and signed by Trump.

Mamdani adeptly underscored that point during his appearance on “Meet the Press.” “I don’t think that we should have billionaires,” he told Welker, “because, frankly, it is so much money in a moment of so much inequality, and ultimately, what we need more of is equality across our city and across our state and across our country.”

His prescription is to raise the state corporation tax by several percentage points to match that in neighboring New Jersey, and to add a 2-percentage-point city surcharge on incomes over $1 million, and use the revenue to finance free bus service, free child care and other public services.

The focus by cable news and other media organizations on the idea that Mamdani would erode New York’s economic base by driving the ultra-rich out of the city was as dubious as it was sadly predictable. Some of them have been feeding on spoon-fed pap by the rich and powerful for so long that — as A.J. Liebling once put it — they need to relearn how to chew. Then Mamdani would get a fair shake, and so would the rest of us.

Business

Companies keep slashing jobs. How worried should workers be about AI replacing them?

Tech companies that are cutting jobs and leaning more on artificial intelligence are also disrupting themselves.

Amazon’s Chief Executive Andy Jassy said last month that he expects the e-commerce giant will shrink its workforce as employees “get efficiency gains from using AI extensively.”

At Salesforce, a software company that helps businesses manage customer relationships, Chief Executive Marc Benioff said last week that AI is already doing 30% to 50% of the company’s work.

Other tech leaders have chimed in. Earlier this year, Anthropic, an AI startup, flashed a big warning: AI could wipe out more than half of all entry-level white-collar jobs in the next one to five years.

Ready or not, AI is reshaping, displacing and creating new roles as technology’s impact on the job market ripples across multiple sectors. The AI frenzy has fueled anxiety from workers who fear their jobs could be automated. Roughly half of U.S. workers are worried about how AI may be used in the workplace in the future, and few think AI will lead to more job opportunities in the long run, according to a Pew Research Center report.

The heightened fear comes as major tech companies, such as Microsoft, Intel, Amazon and Meta cut workers, push for more efficiency and promote their AI tools. Tech companies have rolled out AI-powered features that can generate code, analyze data, develop apps and help complete other tedious tasks.

“AI isn’t just taking jobs. It’s really rewriting the rule book on what work even looks like right now,” said Robert Lucido, senior director of strategic advisory at Magnit, a company based in Folsom, Calif., that helps tech giants and other businesses manage contractors, freelancers and other contingent workers.

Disruption debated

Exactly how big of a disruption AI will have on the job market is still being debated. Executives for OpenAI, the maker of popular chatbot ChatGPT, have pushed back against the prediction that a massive white-collar job bloodbath is coming.

“I do totally get not just the anxiety, but that there is going to be real pain here, in many cases,” said Sam Altman, chief executive of OpenAI, at an interview with “Hard Fork,” the tech podcast from the New York Times. ”In many more cases, though, I think we will find that the world is significantly underemployed. The world wants way more code than can get written right now.”

As new economic policies, including those around tariffs, create more unease among businesses, companies are reining in costs while also being pickier about whom they hire.

“They’re trying to find what we call the purple unicorns rather than someone that they can ramp up and train,” Lucido said.

Before the 2022 launch of ChatGPT — a chatbot that can generate text, images, code and more —tech companies were already using AI to curate posts, flag offensive content and power virtual assistants. But the popularity and apparent superpowers of ChatGPT set off a fierce competition among tech companies to release even more powerful generative AI tools. They’re racing ahead, spending hundreds of billions of dollars on data centers, facilities that house computing equipment such as servers used to process the trove of information needed to train and maintain AI systems.

Economists and consultants have been trying to figure out how AI will affect engineers, lawyers, analysts and other professions. Some say the change won’t happen as soon as some tech executives expect.

“There have been many claims about new technologies displacing jobs, and although such displacement has occurred in the past, it tends to take longer than technologists typically expect,” economists for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics said in a February report.

AI can help develop, test and write code, provide financial advice and sift through legal documents. The bureau, though, still projects that employment of software developers, financial advisors, aerospace engineers and lawyers will grow faster than the average for all occupations from 2023 to 2033. Companies will still need software developers to build AI tools for businesses or maintain AI systems.

Worker bots

Tech executives have touted AI’s ability to write code. Meta Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg has said that he thinks AI will be able to write code like a mid-level engineer in 2025. And Microsoft Chief Executive Satya Nadella has said that as much as 30% of the company’s code is written by AI.

Other roles could grow more slowly or shrink because of AI. The Bureau of Labor Statistics expects employment of paralegals and legal assistants to grow slower than the average for all occupations while roles for credit analysts, claims adjusters and insurance appraisers to decrease.

McKinsey Global Institute, the business and economics research arm of the global management consulting firm McKinsey & Co., predicts that by 2030 “activities that account for up to 30 percent of hours currently worked across the US economy could be automated.”

The institute expects that demand for science, technology, engineering and mathematics roles will grow in the United States and Europe but shrink for customer service and office support.

“A large part of that work involves skills, which are routine, predictable and can be easily done by machines,” said Anu Madgavkar, a partner with the McKinsey Global Institute.

Although generative AI fuels the potential for automation to eliminate jobs, AI can also enhance technical, creative, legal and business roles, the report said. There will be a lot of “noise and volatility” in hiring data, Madgavkar said, but what will separate the “winners and losers” is how people rethink their work flows and jobs themselves.

Tech companies have announced 74,716 cuts from January to May, up 35% from the same period last year, according to a report from Challenger, Gray & Christmas, a firm that offers job search and career transition coaching.

Tech companies say they’re reducing jobs for various reasons.

Autodesk, which makes software used by architects, designers and engineers, slashed 9% of its workforce, or 1,350 positions, this year. The San Francisco company cited geopolitical and macroeconomic factors along with its efforts to invest more heavily in AI as reasons for the cuts, according to a regulatory filing.

Other companies such as Oakland fintech company Block, which trimmed 8% of its workforce in March, told employees that the cuts were strategic not because they’re “replacing folks with AI.”

Diana Colella, executive vice president, entertainment and media solutions at Autodesk, said that it’s scary when people don’t know what their job will look like in a year. Still, she doesn’t think AI will replace humans or creativity but rather act as an assistant.

Companies are looking for more AI expertise. Autodesk found that mentions of AI in U.S. job listings surged in 2025 and some of the fastest-growing roles include AI engineer, AI content creator and AI solutions architect. The company partnered with analytics firm GlobalData to examine nearly 3 million job postings over two years across industries such as architecture, engineering and entertainment.

Workers have adapted to technology before. When the job of a door-to-door encyclopedia salesman was disrupted because of the rise of online search, those workers pivoted to selling other products, Colella said.

“The skills are still key and important,” she said. “They just might be used for a different product or a different service.”

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoSee How Trump’s Big Bill Could Affect Your Taxes, Health Care and Other Finances

-

Culture7 days ago

Culture7 days ago16 Mayors on What It’s Like to Run a U.S. City Now Under Trump

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoVideo: Trump Signs the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Into Law

-

Science7 days ago

Science7 days agoFederal contractors improperly dumped wildfire-related asbestos waste at L.A. area landfills

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoVideo: Who Loses in the Republican Policy Bill?

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoCongressman's last day in office revealed after vote on Trump's 'Big, Beautiful Bill'

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoMeet Soham Parekh, the engineer burning through tech by working at three to four startups simultaneously

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,227