Business

Column: Silicon Valley elites are afraid. History says they should be

It’s develop into a typical chorus amongst a sure set of Silicon Valley elite: They’ve been handled so unfairly. Working example: Even after tinheritor financial institution of selection collapsed spectacularly — in no small a part of their very own doing — and the federal authorities moved with dispatch to ensure all its deposits, tech execs and buyers nonetheless spent the following days loudly taking part in the sufferer.

The distinguished enterprise capitalist David Sacks, who had lobbied significantly laborious for presidency intervention, bemoaned a “hateful media that can make me be no matter they want me to be with the intention to preserve their assault machine going.” Michael Solana, a vice chairman at Peter Thiel’s Founder Fund, wrote on his weblog that “tech is now universally hated,” warned of an incoming “political warfare,” and claimed “lots of people … genuinely appear to need a good quaint mass homicide,” presumably of tech execs.

It was a very galling show; a brand new excessive for a development that’s been on the rise for a while. Amid congressional hearings and dipping inventory valuations, the tech elite have bemoaned the so-called techlash towards their trade by those that fear it’s grown too massive and unaccountable. Waving away legit questions concerning the trade’s labor inequities, local weather impacts and civil rights abuses, they declare that the press is biased towards them and that they’re besieged on all sides by woke critics.

If solely they realized simply how good they’ve it, traditionally talking.

It was mere many years in the past, in spite of everything, that the Silicon Valley elite confronted the energetic menace of precise, non-metaphorical violence. Probably the most adamant critics of Huge Tech of the Nineteen Seventies didn’t write strongly worded columns chastising them in newspapers or blast their politics on social media — they bodily occupied their pc labs, destroyed their capital tools, and even bombed their houses.

“Techlash is what Silicon Valley’s possession class calls it when folks don’t purchase their inventory,” creator Malcolm Harris tells me. “At present’s tech billionaires are fortunate individuals are making enjoyable of them on the web as an alternative of firebombing their homes — that’s what occurred to Invoice Hewlett again within the day.”

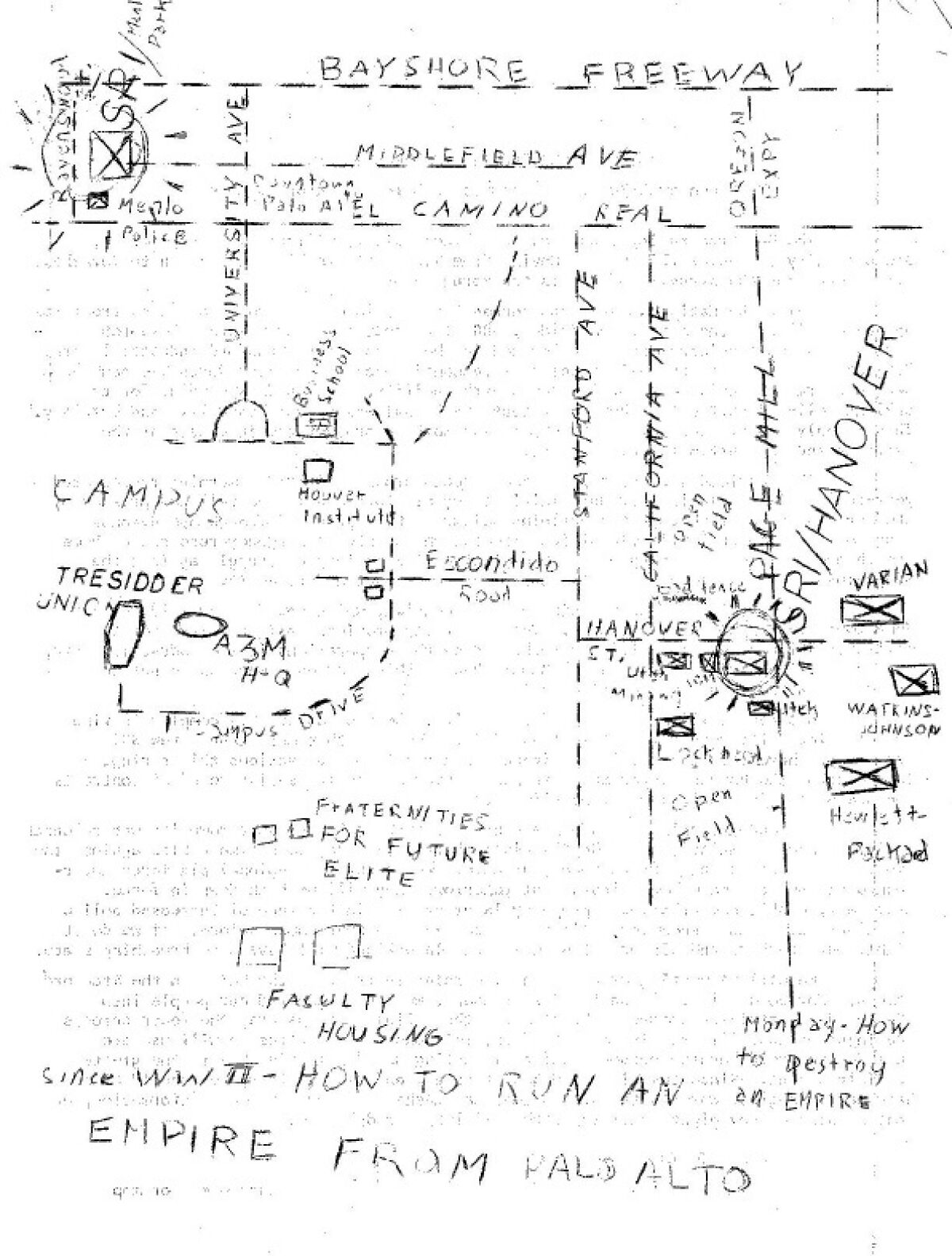

“ Destroy an Empire.” A manifesto and map drawn by pupil radicals to advertise their occupation of the Stanford Analysis Institute.

(The April Third Motion historic archive)

A 1987 article on this newspaper makes his level. When William Hewlett retired from the corporate he based, Hewlett-Packard, or HP, because it’s recognized right now, The Instances devoted a full paragraph to the assorted threats of violence that the billionaire confronted within the Nineteen Seventies:

“In 1971, radical animosities directed on the upscale Palo Alto neighborhood and Stanford College campus introduced terror into the Hewletts’ lives: The modest Hewlett household house was fire-bombed. In 1976, son James, then 28, fought off would-be kidnapers. The identical 12 months, a radical group known as the Crimson Guerrilla Household claimed accountability when a bomb exploded in an HP constructing.”

“ Destroy an Empire.” A map drawn by pupil radicals to advertise their occupation of the Stanford Analysis Institute.

(The April Third Motion historic archive)

Harris is the creator of “Palo Alto: A Historical past of California, Capitalism, and the World,” the guide that’s at the moment the discuss of the city — it simply hit the L.A. Instances bestseller listing — although not for the explanations that the valley’s elites may favor. It’s a sturdy, sprawling historical past that’s intensely essential of the Nice Males of tech historical past, and much more so of the techniques they served. It’s been acquired enthusiastically, as an overdue corrective to the trade’s potent penchant for self-mythology.

And a few of the most potent mythologies, in fact, depend on omission. Take, for example, the favored narrative that whizz youngsters equivalent to Hewlett and Steve Jobs began the pc revolutions from their garages in Palo Alto, the place their starkest opposition got here within the type of sq. outdated companies equivalent to IBM and Xerox — and never precise, bomb-throwing revolutionaries.

Harris’ work reminds us that this was removed from the case. There was a motion much more organized, much more militant, and much more sharply against the Huge Tech firms of the day than something we’ve seen within the final 10 years, and it’s not even shut.

Malcolm Harris is the creator of “Palo Alto: A Historical past of California, Capitalism, and the World.”

(Julia Burke)

After we consider the Sixties in California, we consider disparate, panoramic happenings in an explosive decade; the warfare in Vietnam, the rise of the pc, the scholar protest motion, and so forth. However Harris argues that the pc revolution didn’t merely coexist with the warfare — it fueled it.

“These developments weren’t simply linked,” Harris writes, “they have been the identical factor.”

Intel and Hewlett-Packard revolutionized microchips, alright, however they bought them to the U.S. army, which used them to information the weapons of warfare it was deploying in Southeast Asia. To the scholars, activists, and organizers of the so-called New Left, Silicon Valley was hard-wiring the warfare effort. It was an instrument of oppression, and it had blood on its arms.

David Packard, left, and William R. Hewlett pose in entrance of the Palo Alto storage the place the 2 based their pc firm, Hewlett-Packard.

(Related Press)

All this set the stage for a revolt towards Silicon Valley’s core operators. Palo Alto radicals “singled out Stanford’s industrial neighborhood and its function within the Vietnam Conflict particularly and capitalist imperialism usually,” Harris writes. “And as soon as they received their collective finger pointed in the best place, they attacked.”

That’s not a euphemism both. They actually, fairly bodily, attacked the folks and infrastructure of Silicon Valley that have been linked to the warfare effort.

“The New Left tried to explode roughly each pc they might get their arms on,” Harris says. “And since each have been prone to be discovered on faculty campuses, they received their arms on a bunch of them.” (On the time, keep in mind, there was no PC — computer systems have been nonetheless room-sized machines.)

The reasoning was easy: These computer systems have been making the warfare attainable, each by offering the bodily {hardware} for missile concentrating on techniques and such, and by processing knowledge used to plan fight missions. The warfare precipitated untold struggling and dying; dismantle the warfare machine, hamper the warfare effort. In order that’s precisely what members of Stanford’s left organizers, affiliated with teams equivalent to College students for a Democratic Society (SDS), tried to do.

First, they tried peaceable techniques, equivalent to a strain marketing campaign to halt the manufacture of napalm. It didn’t work. So, taking their cues from the Black Panther Social gathering, which was on the time maybe probably the most highly effective and influential radical left group within the nation, Stanford college students — and even school — adopted direct and militant techniques. They revealed maps of the high-profile tech firms and analysis workplaces in Palo Alto that had gained protection contracts or have been in any other case concerned within the warfare effort.

After the U.S. army bombed Cambodia, the scholar left escalated its techniques by concentrating on the very knowledge processing infrastructure that was aiding the warfare effort.

They occupied the Utilized Electronics Laboratory in Stanford itself. The AEL was an on-campus lab that was finishing up labeled analysis for the warfare effort for the Pentagon, and college students moved to close it down. The occupation ended with a serious concession: that labeled army analysis not can be carried out on campus, and that its sources can be used as an alternative for neighborhood functions.

The victory helped encourage copycat actions throughout the nation — and much more militant ones. College students and activists bombed or destroyed with acid pc labs at Boston College, Loyola College, Fresno State, the College of Kansas, the College of Wisconsin, amongst others, inflicting tens of millions of {dollars} in harm. The explosion on the College of Wisconsin-Madison killed Robert Fassnacht, a postdoctoral researcher who, unbeknownst to the saboteurs, had been working late at evening. IBM workplaces in San Jose and New York have been bombed too.

With momentum at their backs, Stanford radicals determined to up the stakes, and to occupy a fair bigger goal: The Stanford Analysis Institute, or SRI, an off-campus analysis middle that was overseen by the college’s board of trustees, and that had gained monumental army contracts.

“Stanford is the nerve middle of this complicated, which now does over 10% of the Pentagon’s analysis and improvement,” activists wrote in a flier selling the motion. It lambasted the “socialized earnings for the wealthy” generated by the SRI, and the way it was used to “produce weapons to place down insurgents at house and within the Third World.”

This flier had a map too, with the pertinent Huge Tech buildings circled; Hewlett-Packard, Varian, SRI. It was labeled “ Destroy an Empire.”

It was a militant motion, and it was efficient. It deterred funding within the warfare effort, made universities rethink their involvement with the Division of Protection, and it contributed to the eventual withdrawal and coverage reforms gained by the broader antiwar motion.

So why don’t we keep in mind it a lot? Why will we keep in mind the summer time of affection and communitarian counterculture and the Complete Earth Catalog — however not a violent battle over the deployment of know-how and those that profited from it?

Or as Harris places it: “Why are we extra prone to hear concerning the Yippies making an attempt to levitate the Pentagon than SDS efficiently bombing the Pentagon?”

One motive is fairly easy: It’s a feel-bad story that complicates the narrative that has grown more and more central to how we perceive the historical past of how our know-how was invented and produced.

“In Silicon Valley particularly, the clear anti-tech technique of the anti-war motion is inconvenient for the predominant ‘hippies invented the Web’ narrative,” Harris says, “so most of the area’s historians have shunted that half apart.”

However the worry stays. Even when there’s been nothing resembling organized threats on their well-being — guillotine memes on Twitter don’t depend — right now’s tech elites can definitely really feel the resentment brewing.

Perhaps that’s why they’re so delicate to the suggestion that the federal government rescue of SVB was a “enterprise capitalist bailout” — that it was extra particular remedy for a constituency that drives Mannequin Xs to their Tahoe ski chalets, that desires to reap the rewards of investing in world-changing applied sciences whereas bearing so little of the particular danger. A lot of right now’s most seen tech set is aware of that plenty of folks don’t just like the inequality they signify, the preferential remedy they appear to get pleasure from, and the forces their firms and investments have set in movement.

They certainly see Amazon staff and Uber drivers changing into more and more agitated and organized, and brazenly pushing for change towards gross inequalities. They see actions for gender equality and local weather justice at Google and Microsoft.

They see the outrage over the truth that, like its forebears in Hewlett-Packard and earlier Silicon Valley firms, the most recent iteration of Huge Tech has develop into a serious protection contractor too — Google, Amazon, and Microsoft have vied to offer cloud, AI, and robotics to the army — and so they see actions opposing it, as within the #TechWontBuildIt effort, the place tech staff campaigned to reject such tasks. (And hey, HP is nonetheless a protection contractor.) They see backlash towards social media firms giving authoritarian regimes the instruments to commit atrocities. In the event that they knew to look, right now’s tech elites may see numerous the identical kindling that was laid on the bottom within the flamable ‘60s.

“They consider these things always, but it surely’s within the build-a-killer-robot-army manner, not the Patagonia manner,” Harris says, referring to the previous Patagonia billionaire Yvon Chouinard, who gave away his whole firm as a way of combating the ills of maximum wealth.

In different phrases, they’d reasonably sustain the flame wars on social media and construct survival bunkers in Montana than deal with the social ills their critics cost them with exacerbating.

“I believe they’re very, very nervous,” Harris says. If historical past is any precedent — maybe they need to be.

Business

Eight arrested in multimillion-dollar retail theft operation, Los Angeles County sheriff officials say

Eight people were arrested on suspicion of organized retail theft after authorities discovered several million dollars’ worth of stolen medicines, cosmetics and other merchandise at multiple Los Angeles locations, sheriff officials said.

The retail goods were stolen by crews of organized shoplifters at stores in California, Arizona and Nevada, according to detectives. The stolen items were then taken to various locations in L.A. County where they were sold to various “fence” operations, officials said.

Authorities investigating retail theft refer to people who buy stolen goods and then resell them for a profit as “fences.”

The Sheriff’s Department said they had also recovered a stolen firearm and a large sum of cash, according to a release sent late Friday.

The suspects, who were not named, are being held on $60,000 bail each.

Early Thursday morning, sheriff‘s detectives performed raids at a dozen locations in Los Angeles thought to be involved in the crime ring, according to KCAL CBS.

At a small South L.A. market, they found boxes of stolen Motrin, Theraflu and other goods stacked floor to ceiling, the report said. Store tags were still affixed to much of the merchandise. The location appeared to be where the goods were relabeled for sale, officials said.

Detectives said they worked with the help of stores, including CVS and Walmart, to track the illegal operation.

The stolen merchandise is often sold online, officials said, including on Amazon.

The investigation is ongoing. Anyone with information should contact the Organized Retail Crimes Task Force at (562) 946-7270.

Business

Bob Bakish is ousted as CEO of Paramount Global as internal struggles explode into public view

Paramount Global’s months-long internal struggles spilled into full view Monday as Chief Executive Bob Bakish was ousted and pressure mounted for the company’s directors to accept — or reject — a takeover bid by David Ellison’s Skydance Media.

Moments before the company announced its first-quarter earnings, Paramount issued a statement announcing Bakish’s departure. The company said three of its top entertainment executives would run the firm: Paramount Pictures CEO Brian Robbins; CBS CEO George Cheeks; and Showtime/MTV Entertainment Studios chief Chris McCarthy.

Bakish’s firing comes during a tumultuous period for the company as its traditional TV and movie studio businesses decline amid head winds for the media industry. Bakish also was at odds with controlling shareholder Shari Redstone, who is seeking an exit.

Redstone, who has presided over the steep decline of her family’s media heirloom, is in a bind. She doesn’t want the company built by her father, the late, ferocious mogul Sumner Redstone, carved up and sold for parts at auctions. Paramount includes the CBS television network, MTV, Nickelodeon, BET and the Paramount Pictures movie studio on Melrose Avenue.

But Paramount’s common shareholders are wary of the two-phased deal with Skydance because Redstone will get a premium for her family’s shares.

Paramount is in the midst of a 30-day exclusive negotiating period with Ellison, a tech scion whose Skydance Media has teamed up with investment firms RedBird Capital and KKR to acquire Redstone’s National Amusements holding company. On Sunday, Skydance sweetened its offer by $1 billion, with money earmarked for Paramount’s B-class, or nonvoting, shareholders, according to three people familiar with the deal but not authorized to comment. National Amusements holds 77% of Paramount’s voting shares.

The exclusive negotiating period ends Friday. It is unclear whether Skydance and RedBird have given Paramount’s board a deadline to accept its revised offer. Skydance and its partners have been wrangling with Paramount’s independent board members over how much money will go to common shareholders, two knowledgeable people said. Skydance and its partners have pressed for more of the proceeds to pay down Paramount’s debt.

The company’s credit last month was downgraded to “junk” status by ratings agency S&P Global.

Bakish was opposed to the Skydance transaction, a stance that infuriated Redstone, who in 2016 handpicked Bakish to run the company, then known as Viacom. In recent weeks, senior company executives also raised questions about Bakish’s leadership and the strength of his long-range plan in their conversations with board members — a development that expedited Bakish’s departure from the company, the sources said.

Bakish was more open to another proposed deal, favored by smaller shareholders, with private equity firm Apollo Global Management, which has offered $26 billion, including the assumption of Paramount’s debt. Sony Pictures Entertainment has been negotiating with Apollo to join that effort. Most insiders expect that Apollo and Sony would break the company apart, a scenario that Redstone does not want to allow.

Redstone, according to one person familiar with the matter, has also been frustrated with some of Bakish’s decisions, including not selling Showtime, the premium cable network that the company folded into its television networks and streaming effort. Bakish had dismissed a recent offer of $3 billion for the channel from investors, including former Showtime head David Nevins.

Paramount, meanwhile, has lost more than $2 billion on its streaming service, Paramount+.

“Paramount Global includes exceptional assets and we believe strongly in the future value creation potential of the Company,” Redstone said in a statement. “I have tremendous confidence in George, Chris and Brian. They have both the ability to develop and execute on a new strategic plan and to work together as true partners. I am extremely excited for what their combined leadership means for Paramount Global and for the opportunities that lie ahead.”

In addition, the company faces a crucial Wednesday deadline to strike a new deal with cable distribution giant Charter Communications, which runs the Spectrum TV service.

Paramount entered the Charter negotiations with a weak hand — its cable television channels have suffered from falling ratings amid consumers’ shift to streaming. Paramount relies heavily on the revenue it receives from Charter, Comcast, DirecTV and other distributors.

“Paramount still has a popular network, an esteemed studio, and solid streaming services, but its business prospects look tenuous as it looks to sell,” EMarketer senior analyst Ross Benes wrote Monday in an emailed statement. “Arranging a new quixotic leadership structure may appease those looking for new blood. But the dramatic removal evokes a feeling of rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.”

Less than two minutes after Paramount announced Bakish’s departure, the company reported its earnings results.

At the beginning of a call with analysts, company executives said they would not take questions after reporting their financial results. The call lasted slightly less than 10 minutes.

After Cheeks thanked Bakish for “his many years of leadership and steadfast support for all Paramount Global businesses, brands and people,” McCarthy tried to calm concerns about the new triumvirate leadership structure, saying that he, Cheeks and Robbins have worked together for years.

“It’s a true partnership,” McCarthy said. “We have a deep respect for one another, we’re going to lead and manage this company together.”

He said the company’s long-term strategic plan would be focused around three pillars — making the most of the company’s popular content, strengthening its balance sheet and optimizing its streaming strategy.

Paramount reported $7.68 billion in revenue for the three-month period that ended March 31, up almost 6% compared with the same period a year earlier. Paramount reported a net loss of $554 million, but that was less than its loss of more than $1 billion from a year earlier.

The company’s streaming division saw increased revenue of nearly $1.88 billion, up 24% compared with a year earlier. The segment’s quarterly loss was $287 million.

The company’s TV media revenue was aided by CBS’ February broadcast of the Super Bowl, which drew a massive audience. Revenue for the television networks division totaled $5.23 billion, up 1% compared with a year earlier. Paramount’s film division revenue totaled $605 million, up almost 3% compared with a year earlier.

The media empire now known as Paramount Global was formed in 2019 from the merger of Viacom Inc. and CBS Corp. But the combination never convinced Wall Street of its promise. In the last year alone, Paramount Global’s stock has lost nearly half of its value.

“While the mighty Viacom empire declined tremendously under Bakish, who profited handsomely personally, it isn’t clear that another appointed leader would have changed Paramount’s fortune,” Benes of EMarketer wrote in a note to investors. “With a mountain of debt and its primary assets, namely TV, continually losing value, the deep problems facing the company extend beyond any single executive.”

Bakish, who joined Viacom in 1997, was named CEO of Viacom in 2016, after the company’s stock had fallen 45% in two years due to falling ratings at some of its key networks, including Comedy Central and MTV, as well as struggles at its Paramount Pictures film studio.

After Redstone orchestrated the merger of Viacom with CBS, Bakish became CEO of the combined enterprise.

“The Board and I thank Bob for his many contributions over his long career, including in the formation of the combined company as well as his successful efforts to rebuild the great culture Paramount has long been known for,” Redstone said in her statement.

Paramount’s B-class stock rose 3% to $12.25 a share Monday before Bakish’s departure was officially announced. The shares continued to gain slightly in after-hours trading.

Business

Granderson: Here's one way to bring college costs back in line with reality

It took me by surprise when my son initially floated the idea of not going to college. His mother and I attended undergrad together. He was an infant on campus when I was in grad school. She went on to earn a PhD.

“What do you mean by ‘not go to college’?” I pretended to ask.

My tone said: “You’re going.” (He did.)

Opinion Columnist

LZ Granderson

LZ Granderson writes about culture, politics, sports and navigating life in America.

The children of first-generation college graduates are not supposed to go backpacking across (insert destination here). They’re supposed to continue the climb — especially given that higher education was unattainable for so many for so long. The thought of not sending my son to college felt like regression for our family. In retrospect, our conversation said more about the future.

A 2023 study of nearly 6,000 human resources professionals and leaders in corporate America found only 22% required applicants to have a college degree.

The labor shortage is one aspect of the conversation. The shift in academia’s place in society is more significant.

I’m sure that sounds like a good thing for young people joining the workforce. As an educator, my concern is what happens to a society if only the wealthy pursued higher education. Oh, that’s right: We did that already, back before there was a middle class … and paid vacations.

Though it must be said the lowering of hiring requirements isn’t the only threat to the college experience.

Academia has publicly mishandled the campus tensions and student protests that began after the Hamas attack against Israel on Oct. 7, and that certainly hasn’t been good for academia either. Neither has canceling commencement speakers … or commencement itself. Add in the rising costs — up nearly 400% in 30 years compared with 1990 rates — and, well, the college bubble hasn’t quite burst, but it’s hemorrhaging.

Forgiving student loan debt — whether you agree with the idea or not — addresses the past.

The future of colleges depends on the future of labor. If employers are making it easier to enter corporate America without a degree, then universities must adjust how much cash they try to extract from students and their families, because the return on investment will be falling.

College enrollment has already been declining for a decade, and it’s not because Americans have become less ambitious or less willing to invest in their children’s futures. It’s because of eroding confidence that a degree guarantees a higher quality of life.

Imagine that your high school senior is interested in going to college and wants to major in education or communication or the arts. The sticker price for tuition, even at a state school, is going to look pretty steep. If your child were headed toward a degree in engineering or business, that same tuition might feel like a better bet.

There’s no reason tuition rates couldn’t vary to reflect this reality. Colleges and universities should set tuition rates for classes based on the earning potential of the discipline studied.

If our groceries stores can figure out a way to charge us more for organic produce, then surely this great nation can devise a system to set college costs that accounts for future earnings.

For example, according to the National Education Assn., the starting salary for a teacher in California is about $55,000, the fourth highest in the nation. For California residents, the cost to attend UCLA comes to almost $35,000 a year, without financial aid. That math just doesn’t work.

It’s easy to see why 20% of the nation’s teachers work a second job during the school year to make ends meet. Between 2020 and 2022, the nation lost about 300,000 educators, and we’re facing a teacher shortage. To address the issue, a number of states have loosened the teacher certification rules to make it easier to get more bodies in the classroom, which sounds … less than ideal.

Instead, why not lower the cost of credit hours for college students pursuing a degree in education? Wouldn’t parents feel more comfortable knowing the people in the classroom set out to teach and earned the credentials?

If colleges don’t find ways like this to lower costs for at least some students, higher education will become a relic. Just as cable cutting reshaped the economics of the TV industry, the trend of corporate America moving away from degree requirements is going to put pressure on universities to make some big changes.

There have already been tectonic shifts in a short period of time. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, colleges lost international students, who once propped up many institutions by paying higher rates than Americans.

Attendance by Americans is forecast to plummet starting next year. Because of low birth rates and low rates of immigration, the U.S. has fewer young people in the classes graduating from high school after 2025.

And perhaps most importantly, our confidence in college is slipping. In 2015, when my son graduated from high school, Gallup found nearly 60% of Americans had a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in our higher education system. It was under 50% in 2018. It was under 40% last year.

No telling what that number is today.

Which is sad because there is still so much to value — beyond career choices — to a liberal arts education. Given how we live, college is one of the few places we have left in America where young people from different walks of life can meet. That’s important to the health of a nation as diverse — and segregated — as we are.

Colleges will naturally shrink because of demographics, and they can use this time to adjust their business models as well and charge fairer prices. We need young people to be able to replenish all career fields, and that includes art and music and education. It’s time to rethink the economic approach so they aren’t saddled with debt that those careers can’t repay.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoGOP lawmakers demand major donors pull funding from Columbia over 'antisemitic incidents'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHamas ‘serious’ about captives’ release but not without Gaza ceasefire

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoBoth sides prepare as Florida's six-week abortion ban is set to take effect Wednesday

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoColumbia University’s policy-making senate votes for resolution calling to investigate school’s leadership

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoHouse Republicans brace for spring legislative sprint with one less GOP vote

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBrussels, my love? MEPs check out of Strasbourg after 5 eventful years

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoAt least four dead in US after dozens of tornadoes rip through Oklahoma

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoThis Never Happened (2024) – Review | Tubi Horror Movie | Heaven of Horror