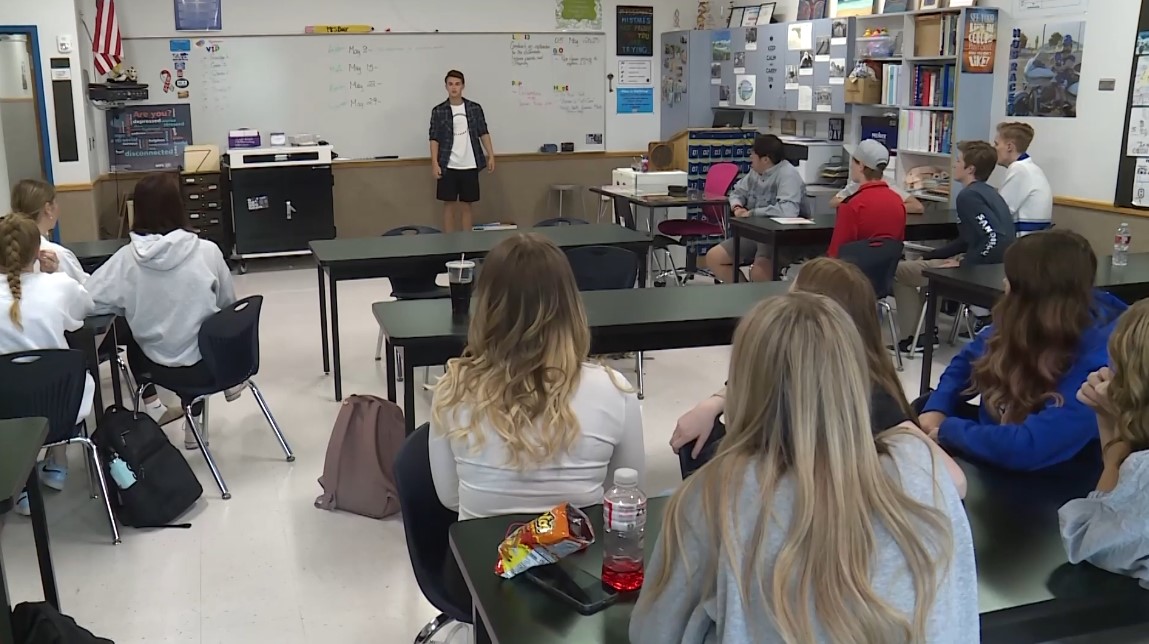

SOUTH JORDAN, Utah – On a recent day at Bingham High School, students brainstormed ways to get the word out: Their school has a new mental health room.

Their work carries urgency because these are members of Bingham’s peer suicide prevention group, Hope Squad. And suicide is the leading cause of death among their peers.

“We spend a lot of time focusing on our school and the kids in our school who need help being heard and being seen,” said Hope Squad member Lucy Herring.

About 40 Utah teens die by suicide each year. Equally concerning is the number who are thinking about suicide.

Student Health and Risk Prevention—or SHARP—surveys administered every two years, show 20% of 10th graders have seriously considered suicide. Nearly as many, 18%, actually made a plan.

“By not uncovering it, not addressing it, we’re basically just letting them suffer in silence. And that, to me, is completely unacceptable,” Michael Staley, suicide prevention research coordinator with the Office of the Medical Examiner said.

And that is why Rep. Steve Eliason, a Republican from Sandy, passed a law in 2020 which provides $500,000 each year for schools to offer mental health screenings.

“For decades, schools have screened for vision issues, hearing issues,” he said. “But for mental health issues, which is the number one cause of death for children in Utah, which is suicide, we didn’t do anything for a long time.”

Despite that funding, less than half of Utah’s school districts take part in the program, and fewer than a dozen charter schools.

“They’re missing out on one of the greatest tools available to them,” said Eliason.

Schools aren’t the only ones missing out. Parents can apply to use their district’s funding to help pay for counseling, insurance deductibles, or other things when the screening recommends treatment they can’t afford. But when the district opts out, that funding isn’t available.

So few districts applied, a new House Bill passed in 2023 imposes a deadline of July 1st for districts to report whether they’re in or they’re out.

“It’s very frustrating,” said Eliason.

Troy Slaymaker wishes these kinds of screenings had been available for his family. He lost his 14-year-old son to suicide, then three years later, his oldest son also died by suicide.

“I’d give anything to have my boys back, anything,” said the South Jordan father.

He knew there were issues but didn’t realize how serious or know what to do.

“It’s one of my biggest regrets, is that I didn’t get my oldest boy help,” he said. “We have the ability to assess it and also the resources to get them help. That’s a no brainer.”

Why don’t more school districts participate in the state screening and funding program?

The Utah State School Board allows districts to decide on their own. And state researchers like Staley acknowledge some may be leery of screening for mental health problems, when they don’t have the resources to help students.

“What happens when someone says yes to these questions, where will they go for help then?” he said.

Many districts not taking part in the mental health screenings are in central Utah. Staley says these areas also tend to have the most access to guns and alcohol and the fewest resources. Yet, this is precisely where the state shows teen suicide rates are highest – in some cases double.

“If we do these screenings, and I think we should, and people are in need, let’s figure out where to take them,” said Staley.

We asked districts why they don’t take part. Davis School District said they have long offered student and family mental health screening events and already have resources working together in what they call a “triage system” to identify problems and then determine how to help the student.

“We have partnerships that have been established for years. Because of that, we have a system in place that is working and continues to work,” said Brad Christensen, director of student and family resources.

Sevier School District Superintendent Cade Douglas says they appreciate the support, but also have their own systems in place.

“We’re hesitant to implement mental health screenings right now because we’re already doing so much in this area,” he said.

Granite School District plans to opt into the program next year.

Jordan School District does all the things the state asks with screenings but didn’t apply for funding. Leaders say screenings have saved lives by getting families resources and starting difficult discussions.

“It’s always helpful if it facilitates open, caring connections and conversations because that’s the key to kids having what they need to get them through a difficult time,” said McKinley Withers, director of health and wellness.

Eliason has another reason he’s pushing for screenings—to prevent school shootings. The same screenings that identify suicide risk could also flag other mental illnesses before they lead to the tragic scenes we see too often.

He hopes these serious issues will push more districts to take full advantage of the funding for school screenings before the deadline.

“I wouldn’t want to be a member of a school board that had walked away from a program like this and decided not to give parents the option to help their children, and later find out a child in that district had died by suicide, or heaven forbid, a mass shooting,” said Eliason.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24982514/Quest_3_dock.jpg)