Alaska

‘She died a hero’: Search underway for woman who fell under ice while trying to save dog

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU/Gray News) – A missing woman who fell under the ice of a river in Alaska was trying to save her dog, according to her family.

Alaska State Troopers on Tuesday identified the missing woman as 45-year-old Amanda Richmond, whose family says was publicly known to many as Mandy Richmond Rogers.

An aerial and ground search began Saturday morning in Eagle River in North Fork after Richmond Rogers was reported missing.

According to Austin McDaniel, communications director for the Alaska State Troopers, the woman went under the ice in a river near the North Fork Eagle Trailhead.

Officials say Richmond Rogers and her husband Brian Rogers were walking along the trail with their dogs when one of them went into the river’s open water. The couple went into the water to search for the dog. Richmond Rogers did not resurface.

Officials say the husband was not injured.

Units with the Anchorage Fire Department and Alaska State troopers were dispatched to assist with the search. A helicopter was also deployed Saturday afternoon. By Saturday evening, officials decided to postpone the search until the next day.

On Sunday, Alaska Wildlife Troopers along with volunteers with the AK Dive Search Rescue & Recovery Team, were at the North Fork Eagle River Trailhead searching for Richmond Rogers.

Those searching were able to get to the site and cut into the ice, allowing the team to deploy technology that may have included divers, sonar and remote operated vehicles underneath the ice. The search on Sunday included several areas of interest that the dive team identified.

“It is certainly a tragic event for the family, our thoughts are with them, especially with the closeness to the Christmas holiday,” said McDaniel. “But our focus is finding the missing woman so the family can have some closure.”

Rep. Jamie Allard, a legislator representing the area in Eagle River where the woman disappeared, wrote of the impact of the tragedy on the close-knit community.

“This incident is a heartbreaking tragedy, and it deeply saddens all of us,” Allard wrote in a statement. “The loss experienced by the family is beyond words, and they have my most heartfelt sympathies in this difficult time. This event is a grave reminder of how quickly situations can turn perilous in natural settings, especially near our river.”

Representative Allard encouraged the Chugiak-Eagle River community to come together to support the family. She also thanked the response from emergency services, along with search and rescue and safety teams, who often demonstrate their dedication to public safety.

Due to areas of thin ice and open water, the teams operated their search and rescue operations when it was safe for them to operate, troopers said.

McDaniel said he urges people to be cautious of thin ice when using snow machines, ice skating, ice fishing and crossing bodies of water on foot.

“If you’re going to be on any frozen lakes, rivers, other type of waterways, make sure you know the depth of the ice,” McDaniel said. “With the interesting winter we’ve been having in Southcentral, Alaska, there could be a substantial amount of snow on top of very thin ice.”

After no luck in finding Richmond Rogers, troopers returned to the area after the Christmas holiday on Tuesday morning to search along the river.

Officials told KTTU that search efforts would continue until dark.

Richmond Roger’s sister, Jennifer Richmond, provided KTUU with pictures of the mother of four and also provided the following statement from Richmond Rogers’ husband, Brian Rogers:

“My wife and I had just spent the last three weeks decorating the house, hanging Christmas lights, buying last-minute presents, wrapping presents, watching our kids compete in the state wrestling tournament, and trying to get out all the Christmas cards to friends and family. It was the first Christmas we were celebrating since the passing of Amanda’s father earlier in the year. We wanted to make it special for visiting family and our four boys. After spending time with her mother and sister the previous two days, the 23rd was our day. We were married on December 23, 2005, making this our 18th anniversary.

“We planned to take two of our dogs for a walk, go on a date, and spend the night at the Hotel Captain Cook. It was a beautiful day. We chose to hike at the North Fork of Eagle River trailhead. We had hiked here many times and was one of Amanda’s favorites. We were having an amazing time watching the dogs play, playing with the dogs ourselves, and admiring the beauty of outdoor Alaska during the winter. We visited with a few friends along the way. We stopped at an especially scenic area along the river to admire the view. We were a bit tired so we laid down on the snow-covered ice to rest and looked at the blue sky above and the cloud formations above the mountains. The dogs ran and played. A short ways away was a small opening in the ice with water flowing, no more than about 18 inches wide. One of the dogs went over to get a drink and fell into the opening. We ran over to the opening. There was only about a five-foot area of uncovered ice downstream from the opening. I thought I saw a flash of a big white paw underneath the ice. Before even thinking, I was jumping into the water to save our dog. I held onto the edge of the ice as I frantically ducked under the ice reaching into darkness trying to feel and grab our dog. I felt nothing. I ran out of breath and jumped out of the opening. I took four steps downstream to look for the dog through the ice again. I turned around and Amanda was getting into the water. I knew from the look on her face she was going in to save our dog.

“She is an emergency room nurse, trained to help and save people. In this situation, she was going to save our dog. I yelled but doubt she even heard me as she was completely concentrating on saving the dog. Before I could get back to the opening to try and grab her I could see her SWIMMING downstream under the ice and then out of sight. I waited and waited and am still waiting. To anyone wondering why we would jump in to save our dog I can only answer, our instincts took over and we went in without thought. Amanda loved her dogs nearly as much as our kids, they were our family. We have a room in our house dedicated to the memory of all our previous dogs. We have tattoos of our dog’s paws. Amanda has around 35 thousand photos and videos on her phone from our 18 years of marriage and a majority of them of our dogs. She did not jump in to save “just a dog,” it was a family member. To me and our four boys, she died a hero.

“Amanda was an amazing mother and has raised four tremendous children. She worked as an emergency room nurse, a death scene investigator, and a pediatric hospice nurse but the job she excelled at was mom. She enjoyed the outdoors, her family, all animals, and adventure. She has touched so many people’s lives for the better. I could go on and on and on. She was a beautiful person with a beautiful soul.

“Our family would personally like to thank the Rankin family, the first responders who responded that day, Anchorage Police and Alaska State Police, the search and rescue workers who have and will work to recover Mandy, my neighbors, Eagle River, the amazing Alaska State Wrestling community, my colleagues with Alaska Emergency Medicine Associates, the Anchorage Medical Community, Mandy and I’s friends and family, those who have or will send meals, and anyone sending thoughts and prayers. I know I am missing so many people but my brain is still in a fog. It is truly incredible the overwhelming support we have received during our crisis. We are blessed to live in such a special place. Thank you.”

Copyright 2023 KTUU via Gray Media Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Alaska

“World’s largest undeveloped gold mine” faces legal challenges from Canada and Alaska tribal nations – KRBD

At the river’s mouth

The Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission is worried about the region’s rivers. They are a group of 15 Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian nations who came together because they believe mining in British Columbia poses a threat to their spawning salmon and hooligan habitats, like the Unuk and Stikine Rivers.

The transboundary commission’s attention is currently on the Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell project, a proposed gold and copper mine at the foot of a glacier just across the Canadian border.

“KSM is on a whole other scale of mining, one of the world’s largest open pit mines, if it’s ever built,” said Guy Archibald, the director of the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission. “Our tribes and communities are directly downstream. We rely on fish and the food security opportunities that the Unuk provides.”

The KSM Project is being developed by Seabridge Gold. According to the Canadian exploration company, the mine could generate nearly 1,500 jobs and over $30 billion for British Columbia and $60 billion for Canada over its projected 60-ish year lifespan.

For Archibald, the stakes are “Billions of tons of acid-generating waste rock just piled into valleys. Valley fills in direct tributaries to the Unuk River. And so it’s almost inevitable that bad things are gonna happen.”

Mine tailings are the materials left over from the mining process, like acidic rock waste, undesirable metals, and the chemicals and discharge from processing the ore. All of this waste is stored in tailings facilities or dammed ponds until it can organically break down. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, many decommissioned mine tailing facilities are designated as Superfund sites.

Archibald cited the Mount Polley disaster, a 2014 failure at another mine in British Columbia that is widely referred to as one of the worst mining disasters in Canadian history. Canadian news outlet The Narwhal reported that KSM’s tailing ponds would be around 28 times the size of the one that failed at Mount Polley. The Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission estimated that KSM’s tailings ponds would require ongoing maintenance for at least 250 years, long after the mine shutters.

A voice in the process

In July, the British Columbia government issued a finding in the permitting process for the project known as a “Substantially Started Determination.” Under British Columbia’s law, environmental permits for development projects like mines come with an expiration date. According to the British Columbia Environmental Assessment Office, that’s partially because the environmental assessment process is constantly evolving – i.e. new science, new information, new regulations. Once a mine reaches a certain stage in development, though, the province can declare that it is far enough along and has met the environmental permitting requirements to move forward without its environmental “stamp of approval” lapsing.

Part of that environmental assessment process involves public comment and “a legal obligation to consult with Indigenous nations whose interests could be affected by the outcome of a substantially started determination.”

“And yet, the Alaska tribes are not really afforded any kind of voice in how this process works out. So we are trying every way possible to try to be sure that our communities are protected,” said Archibald, alleging that tribes in the transboundary commission weren’t afforded a meaningful seat at the table in that process.

In late November, the transboundary commission and SkeenaWild Conservation Trust filed a legal challenge against the British Columbia government. They’re represented by the Canadian law firm EcoJustice and are arguing that the mine was “rubber stamped” – challenging the premise of the province’s decision that the mine is “substantially started.”

The KSM mine received its environmental assessment a decade ago. EcoJustice attorney Rachel Gutman said that the process has changed since then and the province has a “deeper understanding of a rapidly changing climate” and “threats to salmon populations.”

“There are good reasons why the law has expiration dates for environmental assessments, including ensuring that mega projects like the KSM mine do not proceed based on outdated information,” Gutman said in a press release. “This is particularly important in this case due to the rapidly changing climate in Northern BC.”

The challenge also alleged that the province specifically considered whether the “substantially started determination” would help the mine in its timeline to secure outside funding when it issued the determination.

“We believe it is inappropriate for the [British Columbia Environmental Assessment Office], the agency tasked with assessing the environmental impacts of a project, to consider how their decision might support a company with project funding,” said Greg Knox, the executive director of SkeenaWild.

R. Brent Murphy is Seabridge’s Vice President of Environmental Affairs. In an email to KRBD, he wrote that Seabridge’s legal counsel are preparing to defend the validity of British Columbia’s determination. In his view, the Southeast Alaska tribal commission’s “ultimate goal is to halt all mining and exploration activities in the transboundary region.”

Murphy claimed that mining projects like the KSM aren’t responsible for declines in salmon and hooligan habitats. He chalked them up instead to “changes in ocean conditions, declines in quantity and quality of spawning habitat, and overfishing.”

“There is also a misconception that Alaskans were not engaged during the [environmental assessment] process of the KSM Project,” Murphy said about the transboundary commission’s challenge that tribes weren’t properly consulted in the process. “On the contrary, the BC Environmental Assessment Office actively receives input and feedback from Alaskan regulators, tribal groups, and the Alaskan public for any mining project undergoing the EA process within the transboundary region.”

For Archibald and the transboundary commission, though, those requests for feedback amounted to an empty promise. He called British Columbia’s consultation process for Alaskans “everything short of being meaningful or consent-based at all.”

The Southeast Alaska Transboundary Commission’s challenge, as well as their recent petition to an international human rights commission, hinges on their demand to be afforded the same sway in the consultation process as Canada-based First Nations, a request that has been categorically denied by both British Columbia and the larger Canadian ministry.

There is Canadian legal precedent for U.S.-based tribes to be afforded the same rights to consultation as First Nations protected under the Canadian constitution. That precedent is R. v. Desautel, a 2021 Canadian Supreme Court finding. An indigenous American citizen was tried in Canada’s courts for killing an elk in British Columbia without a hunting license. The defendant lived on a reservation in Washington and argued that he was exercising his Aboriginal right to hunt in the traditional territory of his ancestors.

As Archibald put it, the case forced the Canadian Supreme Court to ask a central question: “Do indigenous, non-resident people of Canada – people who live outside of Canada but have ties to traditional lands within Canada – have any rights to those lands? And the Supreme Court said yes.”

“Given the complex nature of an ecosystem, a productive ecosystem, like the Unuk watershed, and the complex nature of one of the world’s largest mines, what the outcome of that is going to be if it moves forward, is really anybody’s guess,” said Archibald.

In a September opinion piece in the Anchorage Daily News, Murphy struck back at the legal challenge and its supporters categorizing Canada’s decision as a “rubber stamp,” saying that Seabridge had already sunk roughly CAD $1 billion into the project which constitutes substantial progress. He also challenged what he called “widespread misinformation” surrounding the mining industry.

Murphy said that the KSM project met British Columbia’s three main criteria for a “substantial start determination” – work had begun on the mine, they’d spent significant money on construction, and they’d received “the support of our First Nations partners.”

The headwaters

The Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha Nation is an Indigenous First Nation in British Columbia that borders the KSM site.

In November, they filed their own legal challenge against British Columbia. Ryan Beaton, who provides legal counsel for the nation, said that the KSM project’s proposed tailings facility is on the nation’s land and the province didn’t properly consult with them either before “essentially greenlighting” the project.

“If we’re going to go ahead with this permitting, and this is going forward, where’s the consultation? Where are the funds to deal with the environmental damage from this?” Beaton asked.

Beaton described Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha as a small tribal nation “surrounded by larger, more powerful or more connected First Nations neighbors.”

Those larger First Nations surrounding the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha’s traditional territory are the Tahltan and the Nisg̱a’a. And both nations publicly support the mine.

If the KSM project is built, Seabridge envisions three open-pit mines that will feed a processing facility and a tailings facility to store mine waste. Seabridge anticipates those mines could produce at least 47 million ounces of gold and 7 billion pounds of copper over their lifespan.

“The concern is a huge amount of toxic waste flowing out onto the territory, into the waterways, destroying the fishing for the nation, affecting wildlife,” he said, explaining the nation’s concerns if one of the dams at the tailing facility failed.

For Beaton and the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha, even if all goes according to Seabridge’s plan, some of the damage has already been done.

“Just the construction of the project on its own terms, if everything goes well, has had a huge impact on their hunting territories, their traditional ways of life, huge swaths of forest cut down, so there’s already been major impact,” Beaton said.

The KSM project has also caused particular friction between the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha and their First Nations neighbors. That’s because Beaton said if the project moves ahead, gold and copper aren’t the only things that will be flowing out of it – so will huge sums of money to the Tahltan and the Nisg̱a’a.

The Tahltan and the Nisg̱a’a both signed agreements with Seabridge over the last decade. Publicly, Nisg̱a’a Nation President Eva Clayton has said that projects like Seabridge’s KSM stand to attract investors to First Nations territories in the Golden Triangle and “improve the quality of life of our Nisg̱a’a and Tahltan people.”

Recently, the two nations announced a partnership to “maximize joint opportunities on the Seabridge KSM Project.”

“On behalf of both the Nisg̱a’a Nation and the Tahltan Nation, I would like to acknowledge Seabridge for their support and encouragement,” Tahltan Nation Development Corporation Chair Carol Danielson wrote in a statement at the time, “and their willingness to actively engage and work with our Partnership on their KSM project, the world’s largest undeveloped gold project.”

Neither Tahltan nor Nisg̱a’a leadership responded to requests for comment.

Beaton compared the tailings facility dispute to hearing there was a big construction project happening in your neighborhood and then finding out “all the toilets for the project were going to be built in your backyard while the money flowed elsewhere.”

“When the [KSM project] is over, the Nisg̱a’a and Tahltan get to go home and the Skii km Lax Ha, this small First Nation, is stuck with a huge waste facility on its territory, and that is not the way Indigenous consultation should go,” said Beaton.

The Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha aren’t strangers to mining, though. They’ve worked with other mining projects in the past and recently signed an agreement with a different company for a neighboring mine.

“Our nation is certainly not anti industry,” said Beaton, adding that the nation does see the benefits mining could have on the province and their communities. “But it’s got to be done responsibly and in a way that respects both the nation’s rights but also the environmental concerns that they have.”

“[Its] the ‘Asserted’ territory of the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha,” said Seabridges’ R. Brent Murphy about the First Nation’s claim that the land for the tailing facility belongs to them. “While they have sought recognition of their ‘exclusive’ rights to this area, it is currently not recognized by the government.”

The federal government of Canada marks the site of the proposed tailings facility as traditional Tahltan territory.

In their legal challenge, the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha allege that this comes from a complex history of misinterpreted treaties and shaky ethnographic accounts that essentially, as Beaton puts it, “writes the Skii km Lax Ha out of their own history on their own territory.”

This assertion is backed by a 2021 report from British Columbia’s Attorney General, as well as a 2017 environmental assessment of a different mine, that supports the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha’s exclusive rights to the area where the tailings facility will be located.

“We’re not asking them to take our word for it,” Beaton said. “We’re asking the province to act on their own assessment.”

Similar to the legal challenge EcoJustice filed on behalf of Alaska tribes across the border, the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha’s legal complaint is lobbied against the provincial government. According to Beaton, that’s because the small First Nation is alleging that the province officially recognized their territory but because of their size and their lack of support for the KSM project, their constitutional right to consultation was minimized.

“The province is really picking and choosing who gets rights, and that is not appropriate. It’s really colonialism in action,” said Karen McCluskey, Beaton’s co-counsel representing the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha.

For Seabridge, the could-be world’s largest gold mine passed its comprehensive seven-year environmental review process and according to Murphy, the company plans to invest millions of dollars annually into ongoing water quality reviews. For him, the province’s determination just reflects that Seabridge has done its part in making sure the project is safe and sustainable. He also continuously pointed to the support of their Indigenous partners – the Tahltan and Nisg̱a’a – and how they’ve allowed the project to move forward on their ancestral lands.

“The benefits are flowing to neighboring First Nations, to the government, and to industry. You know, the Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha nation has said they would like to have no dump on their land. That’s their position,” Beaton said.

The ball is currently in British Columbia’s court to determine how long they’ll need to respond to these legal challenges on both sides of the border. Beaton estimated the whole process could take about a year.

For the KSM mine, Seabridge is hoping to solicit a partner for the venture, another mining company big enough to build and operate a mine this scale. After that, they anticipate construction on the mine would take about five years.

Alaska

2 dead, 2 injured in Seward Hwy head-on collision

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – A head-on collision involving two vehicles has left two dead, and two injured along the Seward Highway at mile point 82 near Portage, according to the Anchorage Police Dept. (APD).

At around 4:11 p.m. Anchorage Police Department, Whittier Police Department, Anchorage Fire Department, and Girdwood Fire Department responded to a collision with reported injuries.

Authorities investigated the scene and determined it was a head-on collision and the Whittier Police Department confirmed two were deceased.

The other two individuals involved sustained injuries but APD says it is unclear at this time if they are life-threatening.

APD reported at the time of publication that first responders remain on the scene and are managing the situation so travelers should expect delays.

The inbound and outbound lanes of the Seward Highway initially closed around 5:30 p.m. and there is no estimation as to when they will open back up.

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2025 KTUU. All rights reserved.

Alaska

Pediatrician Chosen for Alaska Mental Health Trust CEO – Alaska Business Magazine

“I am honored with the opportunity to lead an organization that has such a unique and important role in supporting Trust beneficiaries and the organizations that serve and support them,” says Wilson. “I look forward to working with the talented staff at the Trust Authority and the Trust Land Office who share my passion for improving the lives of Trust beneficiaries.”

Wilson grew up in Alaska and, in recent years, returned to the state following her medical career. She originally worked as a licensed pediatrician before advancing into leadership positions at Permanente Medical Group, including Executive Medical Director and President of The Southeast Permanente Medical Group in Atlanta. Wilson brings to the Trust extensive executive experience coupled with a thorough understanding of the systems of care that serve and support Trust beneficiaries.

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoBook Review: ‘Somewhere Toward Freedom,’ by Bennett Parten

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoOpinion: Biden delivered a new 'Roaring '20s.' Watch Trump try to take the credit.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoJudges Begin Freeing Jan. 6 Defendants After Trump’s Clemency Order

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoInstagram and Facebook Blocked and Hid Abortion Pill Providers’ Posts

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoHamas releases four female Israeli soldiers as 200 Palestinians set free

-

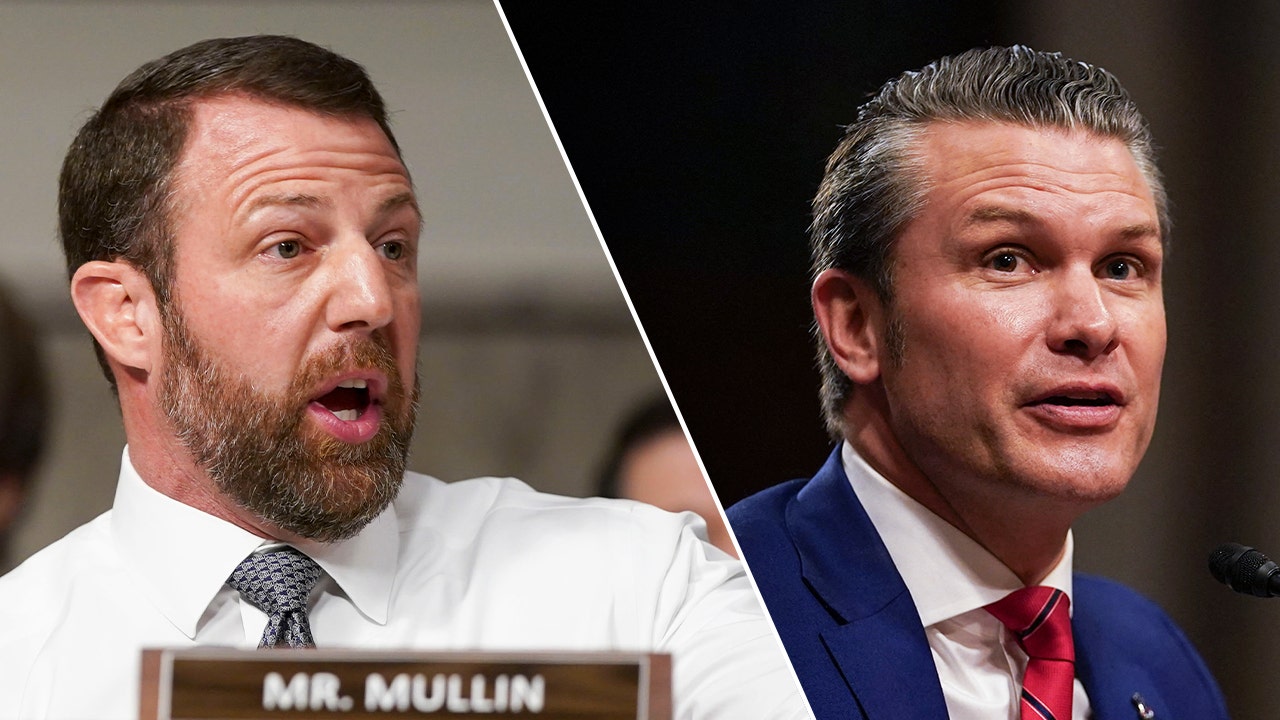

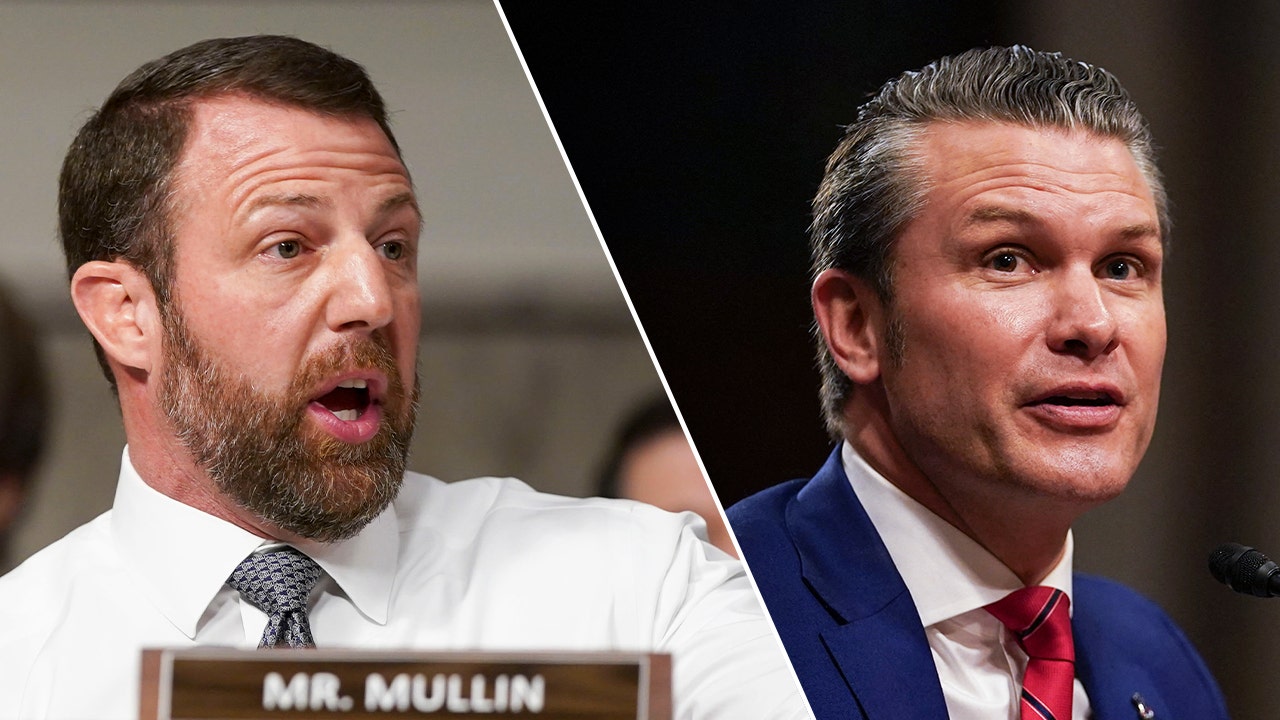

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoOklahoma Sen Mullin confident Hegseth will be confirmed, predicts who Democrats will try to sink next

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoIsrael Frees 200 Palestinian Prisoners in Second Cease-Fire Exchange

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA Heavy Favorite Emerges in the Race to Lead the Democratic Party