Alaska

Comparing costs among Alaska towns

Juneau, Alaska (DOL) – Within Alaska, the cost of living tends to be lowest in the largest cities and smaller communities on the road system. Costs rise as populations fall and barriers to access increase.

Between urban areas, costs differ more by the type of expense than overall. Anchorage and Fairbanks rank closely for overall costs, for example, but Anchorage home prices are higher while Fairbanks pays significantly more for utilities.

In other areas, expenses depend on how remote they are.

Everything costs more in rural Alaska, and shipping plays a primary role in those higher costs. Comprehensive cost-of-living measures are scarce

for much of Alaska — the last statewide survey was completed in 2008.1 This article looks at the two broad cost-of-living indexes available, albeit for a limited list of Alaska communities, then drills down to comparisons around the state for two major spending categories, housing and fuel, for which more sources are available.

Two broad in-state cost-of-living indexes cover only some towns

Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau, and Kodiak

The most complete cost-of-living measure for in-state comparisons is the Council for Community and Economic Research survey, which the Alaska-U.S. comparisons that begin on page 9 use extensively. (See that article for more about this survey.)

C2ER tracks prices in four Alaska cities: Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau, and Kodiak.

All index values are relative to the survey average for the U.S., set at 100.

In 2022, the overall cost of living in the four Alaska cities ranged from a low of 123 in Fairbanks to a high of 129 in Kodiak. In other words, their costs were 23 percent and 29 percent higher than the average, respectively. (See the table on page 10.)

Alaska cities’ overall scores were similar, but some 1The McDowell Group (now McKinley Research), Alaska Geographic

Differential Study 2008 expenditures differed notably.

Juneau and Anchorage have higher housing costs than Kodiak and Fairbanks. Utility costs also vary depending on winter severity and which energy source a city relies on for heat. Fairbanks’ utility costs are far higher than the other cities and were more than double the survey aver-

age (209) in 2022. Fairbanks winters are extreme, and households primarily use heating oil. Utilities were lower in Juneau and Kodiak, where heating oil is also the dominant heat source, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, but winters are milder. Anchorage was the lowest because of its natural gas. (See the fuel section on page 14.)

Grocery prices were lowest in Anchorage and Fairbanks (the largest cities), higher in Juneau, and highest in Kodiak, the smallest.

Apartment rents and single-family home sales prices in select Alaska areas

Notes: Median adjusted rent includes utility costs. Utility adjustments use 2022 data. Percent change is from the same period the previous

year.

*Bethel is new to the survey in 2023. Bethel’s rent does not include the utility adjustment.

Source: Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development, Research, and Analysis Section and Alaska Housing Finance Corporation

Examining housing and fuel costs around the state

Sales prices, rents up in all covered areas

Housing costs make up the largest share of most households’ budgets, and many areas saw large increases over the past year.

Each year, in partnership with the Alaska Housing Finance Corporation, DOL conducts statewide quarterly housing market surveys of lenders and an annual rental survey in early March for several areas. (See the tables above.)

In 2022, the average single-family home cost $422,484. Average prices ranged from a low of $337,329 in Fairbanks to a high of $513,119 in Juneau.

Historically, home prices have been higher than the statewide average in Anchorage and Juneau and lower in the Fairbanks North Star, Matanuska-Susitna, and Kenai Peninsula boroughs. Bethel, the only rural area broken out separately, also tends to be high, but prices can be volatile in small areas because just a few transactions can swing the average.

Consistent with national trends, home prices in Alaska have risen considerably in recent years.

In 2022, Alaska’s average sales price rose 8.7 percent after increasing 8.9 percent in 2021. (For more on the current Alaska housing market, see the May 2023 issue of Trends.)

Higher home prices and rents tend to go hand in hand, but rents rank higher than sales prices in Fairbanks and Kodiak, which have large military populations with generous housing stipends.

The University of Alaska Fairbanks is another steady source of rental demand.

In March, the median adjusted rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the Department of Labor’s survey ranged from a low of $1,055 in Wrangell-Petersburg to a high of $1,532 in Anchorage.

Adjusted rent includes the cost of utilities,2 whether they are included in the rent check or paid separately by the tenant.

Rent was highest in Bethel, which DOL added to the survey in 2023, and because Bethel’s rent doesn’t include the adjustment for utilities, it was probably even further above the other areas than the rent table shows.

Rents were higher than the previous March in all areas.

In the five largest markets, rents rose 9 percent in Fairbanks and Mat-Su, 7 percent in the Kenai Peninsula Borough, 5 percent in Anchorage, and 4 percent in Juneau.

Survey samples vary by year and depend on landlord participation, so these numbers can be more volatile in smaller areas.

Inflation, limited availability, and rising costs have pushed rents upward in recent years.

The September 2023 issue of Trends will detail this year’s rental survey results.

This article uses 2022 utility adjustments for 2023 rents, as they were the most recent available at the time of publication.

“During the pandemic, and even a little bit going into the pandemic, Alaska had for the first time in its history, negative inflation. So, prices actually went down. Then prices went way up during COVID. And they’re just coming down now in the most recent data,” Dan Robinson, Chief Researcher and Analyst for the Alaska Department of Labor’s Economic Trends Magazine said while on Action Line. “In terms of the drivers, it’s an unusually messy set of factors because again of the pandemic. What people bought changed, how much people bought changed, supply chain, work chains were disrupted. So, some of what we can tie to the pandemic is kind of going away, things are normalizing. But there are some things, housing being the main one, that are keeping inflation being a little higher than average.”

He talked more about housing.

“When we talk about overall inflation, housing has the largest weight. Which means, it’s what the average consumer spends the highest percentage of their money on, which makes sense. So, what housing does, whether it’s rising or falling, influences disproportionately what’s going on in the overall inflation rate,” Robinson said. “Juneau is interesting and Alaska overall because despite not a lot of population growth for a while, housing has continued to go up. One thing this article talks about though is that lots of U.S. cities have noticeably more expensive housing than any Alaska city. So, as expensive as things are here, you’d have it a lot worse if you lived in Honolulu, San Fransisco, a long list of other cities.”

Double-digit percent jumps in fuel prices

Fuel prices in the 2023 winter survey had risen significantly from last winter’s survey, which was completed before the oil price spike in late February 2022. Heating oil’s survey average, excluding the North Slope, rose 34 percent over the year, from

$5.03 to $6.72 per gallon. Gasoline went from $5.31 to $6.70. While the winter survey showed fuel prices rose significantly over the year in most places, they had fallen in some communities since the summer survey, especially in places where fuel is delivered throughout the year.

Fuel prices fluctuate constantly, but heating oil and gasoline prices remain stable longer in areas that only receive shipments a few times a year.

In winter 2023, many communities were still paying the higher prices of the previous summer, when they received most of the year’s fuel.

While the Alaska fuel price survey is semiannual, national price data collected more frequently show how volatile prices have been over the past few years, and while prices have fallen from the 2022 highs, they remain elevated from most of the previous few years.

National gasoline prices dropped below $2 a gallon in 2020 when the pandemic began, rebounded and continued to rise through 2021, then spiked to around $5 in late February of 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine.

The most recent data show prices have come down to less than $4.

Public health insurance premiums

For a typical household, medical care is a small share of out-of-pocket spending — but medical costs can be high for some people and rise with age.

Health care is also a major cost for employers, as those who offer it typically pay the lion’s share of the premiums.

Only a small share of Alaskans are insured through the public health care marketplace, but those premiums provide a state-level measure for medical cost comparisons. In 2023, the average benchmark premium for Alaska was $762 per month.

For comparison, the U.S. average was $456. Alaska ranked fourth-highest in 2023 (similar to recent years) behind Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming and ahead of New York and Connecticut. Before 2018, Alaska’s premium topped the list.

To read the full Trends article, click here.

Listen to the full Action Line here.

Alaska

Alaska baseball exhibit launches state’s participation in America250

Next year, cities and states across the nation will be honoring the American semiquincentennial, marking 250 years since the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Each of the 50 states will have unique roles in the celebration and Alaska has already established a theme for its participation in America250: baseball.

State historian Katherine J. Ringsmuth and the Alaska Office of History and Archaeology have developed a traveling baseball exhibit, showcasing a uniquely Alaskan stitch in the American tapestry.

“Alaska’s Fields of Dreams: Baseball in America’s Far North” features nine panels — each representing an inning — that explore Alaska’s role in the national pastime.

From the Knock Down and Skin ‘Em club of St. Paul Island to the game’s expansion north to Nome and the formation of the Alaska Baseball League, the exhibit covers more than 150 years of baseball in Alaska.

Late last year, Gov. Mike Dunleavy signed Administrative Order 357, designating the Alaska Historical Commission as the state agency to coordinate with the national America250 organization and plan and coordinate events.

That put Ringsmuth and the commission, which is headed by Lt. Gov. Nancy Dahlstrom, into action to develop Alaska’s involvement.

And while some states will highlight their roles during early eras of America, Alaska has a relatively short history as part of the U.S. as the 49th state admitted. But as Alaska developed as an American territory even before statehood, baseball was a connection to the U.S.

“What we’re seeing by the 1910s, 1920s with the establishment of places like Anchorage, you see these places turning into real American towns,” Ringsmuth said. “And baseball is part of that agent that’s carrying those values.”

Alaska’s history with baseball is diverse both geographically and in the makeup of its participants.

The exhibit documents the history of Alaska Native baseball and details games in Goodnews Bay in Western Alaska and in Nome, where miners used burlap bags as bases to play on the tundra. It also covers Alaska women who play the game, the arrival of Negro League’s great Satchel Paige in Alaska in 1965, and Midnight Sun games.

The theme for Alaska’s involvement in the America250 is “History for Tomorrow,” and Ringsmuth said that look to the future is a nod at younger populations.

“I thought, let’s do something that makes our young people filled with optimism and (shows) that they can dream for tomorrow, and this can be the promise of tomorrow,” she said. “And I thought sports was a fantastic way to do that.”

The exhibit was shown at a number of places throughout the state over the summer. On Wednesday, the display will be at the Bear Tooth Theatrepub as part of the AK Sports Shorts storytelling event.

One of the seven speakers is Olga Zacharof of St. Paul, who will talk about the Knock Down and Skin ‘Em club, considered Alaska’s first baseball team.

Ringsmuth and Lorraine Henry with the Alaska Department of Natural Resources will also be on hand to talk to attendees about America250-Alaska during the intermission.

The event starts at 6 p.m. and tickets are $20. A portion of the proceeds goes to the Healthy Futures Game Changer program, which “provides small grants to youth from low income families to remove barriers to participation in sports and recreation such as equipment, fees, and transportation costs,” according to its website.

Ringsmuth said the exhibit is a device to get people to learn about the history of baseball in Alaska and an entry into other America250-Alaska events and activities.

The state has big plans for the Week of Dreams — a weeklong tribute to the nation’s pastime culminating on July 4, 2026.

Plans for the week include youth games, legacy softball and Indigenous baseball games and celebrating the addition of Growden Memorial Ballpark in Fairbanks to the National Register of Historic Places.

It will also highlight the Knock Down and Skin ‘Em club, which was founded in 1868.

With the help of Anchorage coach and former pro player Jamar Hill, Ringsmuth connected with the Major League Baseball commissioner’s office, and the event will bring up former MLB players who are also ABL alumni for the Week of Dreams events.

Even active MLB players like Aaron Judge, who was a former star for the Anchorage Glacier Pilots, could be involved via remote methods.

“Our office is talking about doing a story map we can (post) online,” Ringsmuth said. “You know, call us and we’ll record you. What’s your story of playing in Alaska? What’s your favorite memory?”

“We can still engage the players who are going to be a bit busy next summer.”

Alaska

Bartlett pulls out 3OT thriller, Dimond rides the storm: Alaska high school Week 5 roundup

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – As the playoffs inch closer, each successive week of high school action carries more seeding implications and general importance – and one could tell as much from watching the slate of games this weekend.

Every team in the state was active this week except Seward in 9-man, giving plenty of opportunities for statement performances at every level.

Bartlett 12 – Service 6 (3OT)

Service played host to Bartlett looking to extend its record to 5-0, but couldn’t survive a chaotic, back-and-forth game that featured 12 combined turnovers and defensive dominance on both sides.

Golden Bears standout Deuce Alailefaleula notched a first-quarter interception and fell on an errant Service snap to tie the game at 6 late in regulation. After two overtime frames with no scoring, Bartlett back Colt Jardine plunged in for the walk-off touchdown on the first play of triple-OT.

Dimond 25 – Colony 22

The Dimond Lynx invaded a wet and wild Pride Field to take on Colony, and weathered the storm by scoring 19 unanswered points to eke out their first win of the season.

Colony fans huddled underneath tents and umbrellas watched in horror as Dimond surged ahead on a late touchdown strike, before the Knights’ last-gasp drive ended in a sack.

Eagle River 14 – Palmer 31

Though it was a much tighter contest most of the way than the final score would indicate, Palmer’s high-powered offense continued to produce in a similarly rainy matchup with Eagle River.

Twenty-four unanswered Moose points helped Palmer extend its winning streak to four, and secured its first 4-1 start since 2013.

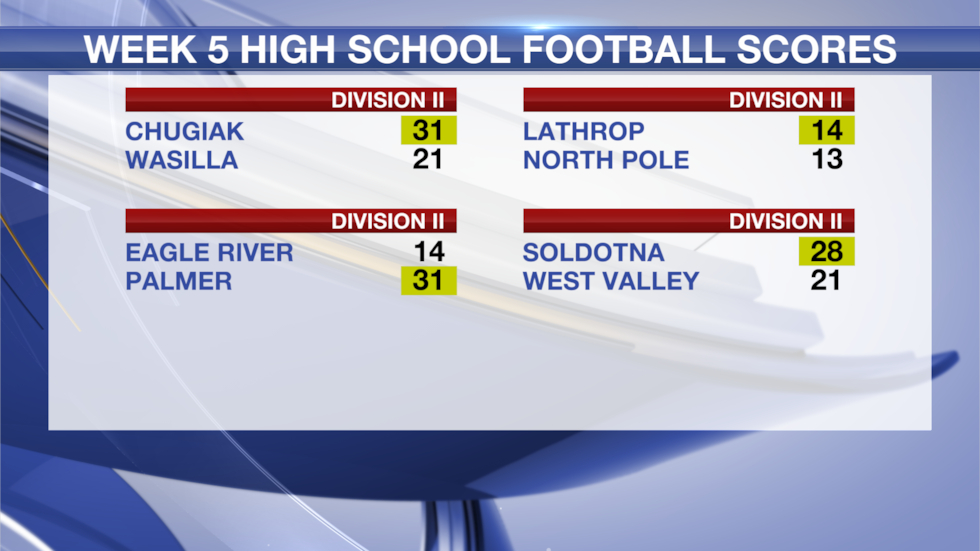

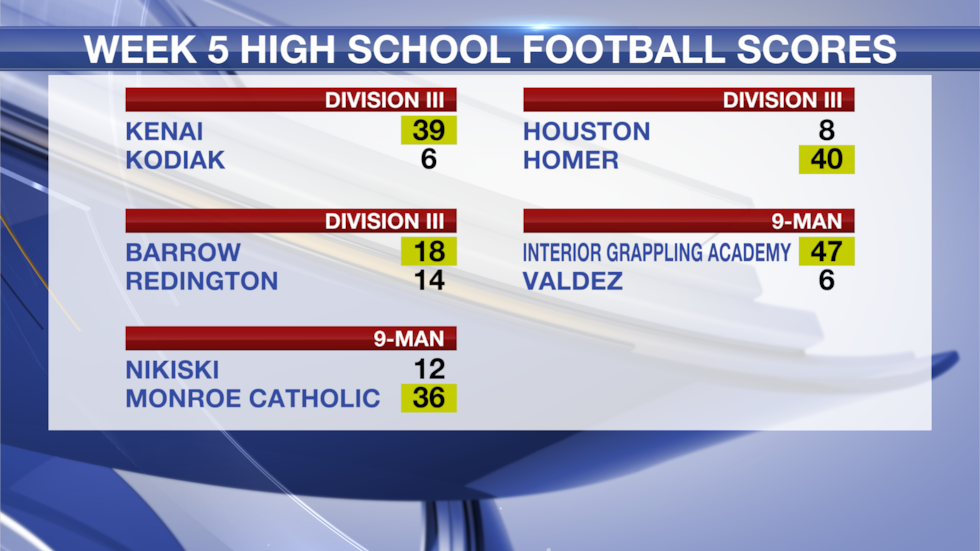

WEEK 5 HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL SCORES

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2025 KTUU. All rights reserved.

Alaska

UPDATE: 911 outage continues in Anchorage

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – The Anchorage Police Department said an outage continues to impact the Anchorage 911 system.

It continues to encourage people in Anchorage who need to use the service to dial 3-1-1 and select option one, or call (907) 786-8900 to connect with police.

ORIGINAL: Anchorage is experiencing a 911 and voice service outage, Alaska Communications told Alaska’s News Source Friday evening.

Alaska Communications spokesperson Heather Cavanaugh said disruption involves home and business landline service as well as 911 calls in Anchorage.

Technicians are working to restore service, but there is no estimated time for when it will be back online, Cavanaugh said. The cause has not been identified, though crews are investigating the source.

“Technicians are still on site working to restore service as quickly as possible,” Cavanaugh said at about 9:40 p.m. Friday night.

Police urged residents to use alternative numbers to reach emergency dispatchers while the outage continues. Anchorage residents can dial 3-1-1 and select option one, or call (907) 786-8900 to connect with police.

Anchorage police first reported a statewide outage late Friday afternoon. Alaska Communications confirmed this evening that the issue is limited to the greater Anchorage area.

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2025 KTUU. All rights reserved.

-

Finance6 days ago

Finance6 days agoReimagining Finance: Derek Kudsee on Coda’s AI-Powered Future

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoHow Nexstar’s Proposed TV Merger Is Tied to Jimmy Kimmel’s Suspension

-

North Dakota6 days ago

Board approves Brent Sanford as new ‘commissioner’ of North Dakota University System

-

World1 week ago

Russian jets enter Estonia's airspace in latest test for NATO

-

Crypto5 days ago

Crypto5 days agoTexas brothers charged in cryptocurrency kidnapping, robbery in MN

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoSyria’s new president takes center stage at UNGA as concerns linger over terrorist past

-

Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoThese earbuds include a tiny wired microphone you can hold

-

Culture5 days ago

Culture5 days agoTest Your Memory of These Classic Books for Young Readers