Sports

‘An unforgettable experience.’ Jack Flaherty’s full-circle journey back to Dodger Stadium

Even before he learned how to walk, Dodger Stadium has been part of Jack Flaherty’s origin story.

It’s where the new Dodgers pitcher first visited at 6 months old, and would return frequently alongside his mom, Eileen, sometimes as often as 20 games per year.

It’s where his early love for the game was planted and nurtured, putting him on a path to the big leagues that first began in Sherman Oaks Little League.

It’s also where — before becoming a first-round draft pick, one-time Cy Young Award contender, and resurgent veteran pitcher acquired by the Dodgers in a blockbuster trade last week — Flaherty produced one of the brightest glimpses into his big-league destiny.

On May 31, 2013, in the CIF Southern Section Division I championship game with his Harvard-Westlake high school team, he pitched a shutout while driving in his side’s lone run in a title-clinching 1-0 win.

“That day,” former Harvard-Westlake coach Matt LaCour said, “kind of exemplified who he was.”

Tyler Urbach (17) and catcher Arden Pabst (7) rush pitcher Jack Flaherty (9) after winning the Southern Section Division 1 championship at Dodger Stadium on May 31, 2013.

(Patrick T. Fallon / For The Times)

In some ways, it was the start of a journey that will come full-circle Friday, when Flaherty — whose 8-5 record and 2.80 ERA make him one of the most important pitchers on the Dodgers starting staff — will make his much-anticipated home debut.

“I’ll have to probably take a breath and gather myself,” Eileen Flaherty said this week. “Because, he’s been there before, but now he has a Dodger uniform on.”

Flaherty’s future first became clear when he arrived at Harvard-Westlake’s Studio City campus, quickly making an impression on the school’s burgeoning baseball program.

“He was kind of touted as, ‘Oh, we have this incoming freshman who is super athletic,’” said Boston Red Sox pitcher Lucas Giolito, a fellow Harvard-Westlake product who was two years ahead of Flaherty in school. “He was like, varsity-as-a-freshman type of talent.”

Only, early on, Flaherty’s most obvious talents weren’t on the mound.

While the right-handed pitcher had sharp command and decent — though hardly overpowering — velocity as an underclassman, his tools as an infielder initially looked more promising.

“Everyone thought he would be a position player,” noted Harvard-Westlake’s then-pitching coach Ethan Katz (who has gone on to become the Chicago White Sox’s major-league pitching coach).

“He was gonna be the shortstop for the next four years,” Giolito said.

In Flaherty’s sophomore season, however, two things changed.

First, Katz helped Flaherty develop his now-signature slider, watching in amazement as the teenager quickly honed the pitch.

“I would tell him every day at practice, ‘Pitching first. Make sure you come down and see me,’” Katz recalled this week. “When he developed his slider sophomore year, that’s when he really took off.”

Then, when Giolito (the team’s senior ace and a potential No. 1 overall draft pick) blew out his elbow earlier in the year, Flaherty was elevated in Harvard-Westlake’s rotation, emerging as a reliable sidekick to another future MLB star, current Atlanta Braves pitcher Max Fried.

“That was kind of the beginning right there,” Giolito said of watching Flaherty that season. “It was like, this guy is a good hitter and a good infielder, but there’s something special about what he’s doing on the mound.”

With Giolito and Fried in the pros as first-round picks in 2013, Flaherty’s profile as a pitcher only continued to explode. He added life to his fastball. He put more bite on his slider. And he began to refine his mental approach, shifting more of his focus primarily to the mound.

“I get my work ethic from my mom, but also from the way that we worked [at Harvard-Westlake],” Flaherty said. “The way we went about our business, the way that we worked, the way we stayed after [practice]. Everything was detail-oriented.”

In that environment, Flaherty flourished.

In his junior year, he went 13-0 with a 0.63 ERA, earning National Player of the Year honors from Maxpreps while helping lead Harvard-Westlake to the CIF Southern Section Division 1 title game.

The added bonus: The final is annually played at Dodger Stadium.

“We obviously wanted to play for a CIF Championship,” Flaherty said this week, sitting on a railing of the Dodger Stadium dugout. “But we knew, with that, came being able to play here, which was just an unforgettable experience.”

Indeed, 11 years later, Flaherty and those close to him still remember the day vividly.

In the morning, the pitcher struggled to focus on his finals in school. “I don’t think I did well on them,” he joked.

As the team took a bus to the game, Eileen and other parents gathered for a meal, superstitiously repeating their outfits from each of the team’s previous playoff games. “I wore a pink shirt, like, the whole time,” she laughed.

Minutes before first pitch, though, Flaherty sat in the dugout with a quiet confidence, seemingly unfazed by a crowd of several thousand around him.

“You see it in championship games all the time,” LaCour said. “A lot of guys at that age, when the crowd gets loud, big environments, they kind of fall apart. But there was no fall apart in Jack. You knew what you were gonna get. You knew he was gonna execute and attack.”

Attack, Flaherty did, racking up eight strikeouts, giving up just six hits and escaping jams in both the third inning (leaving the bases loaded) and the seventh (when his left fielder threw out a runner at home plate).

“That’s game over,” LaCour thought to himself after the seventh-inning play at the plate. With Flaherty on the mound, “that ain’t happening again.”

By that point, Flaherty’s bat had also given Harvard-Westlake a 1-0 lead, driving in the game’s only run on a full-count single in the third.

“I was in Florida rehabbing from Tommy John [surgery], and I watched a live stream on my laptop,” said Giolito, who’d been drafted by the Washington Nationals the previous year. “I was fist-pumping and cheering. My roommate was like, ‘What the hell are you doing?’”

Full pandemonium followed the final out, which not only clinched a Southern Section title for Harvard-Westlake, but also a National No. 1 ranking from both Perfect Game and Baseball America.

“Four or five years before he got there, that program was a team that won like two games a year,” Katz said. “For the program, it was significant. It put Harvard-Westlake on a bigger map.”

Same went for Flaherty, who surged up draft boards during an equally dominant senior season in 2014 (he finished his high school career on a 23-game winning streak as a pitcher), before being drafted 34th overall by the Cardinals, giving Harvard-Westlake three first-round pitchers in three years.

“My time there was very instrumental,” Flaherty said this week. “Just in the way I continue to go about my business.”

Friday won’t be Flaherty’s first trip back to Dodger Stadium since. In his breakout 2018 season with St. Louis, he struck out 10 in a six-inning, one-run start. As a Cy Young candidate the following year, he spun seven scoreless innings while fanning 10 again.

Flaherty’s most recent trip was less memorable, a five-run clunker last April amid a career-worst season.

But this year, the veteran pitcher has regained his old, familiar dominance, leading him on a nostalgic road back to Chavez Ravine.

“It was in the back of everybody’s mind that the Dodgers would be buyers and the Tigers would be sellers, and hey wouldn’t that be cool,” said LaCour, who is now Harvard-Westlake’s athletic director. “So I think everybody’s looking forward to this weekend, and see him wear the white uniform at the stadium.”

Sports

Tyler Reddick wins 2026 Daytona 500

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

The 2026 Daytona 500 proved once again that it’s the last lap that counts.

Tyler Reddick, who drives for Michael Jordan’s 23XI Racing, was in first place when he crossed the line at Daytona International Speedway and won the Daytona 500 for the first time in his career. He didn’t lead a single lap until the very end.

Tyler Reddick, driver of the #45 Chumba Casino Toyota, and Carson Hocevar, driver of the #77 Spectrum Chevrolet, race during the NASCAR Cup Series Daytona 500 at Daytona International Speedway on Feb. 15, 2026 in Daytona Beach, Florida. (Patrick McDermott/Getty Images)

Tyler Reddick, driver of the #45 Chumba Casino Toyota, lifts the Harley J. Earl Trophy in victory lane after winning the NASCAR Cup Series Daytona 500 at Daytona International Speedway on Feb. 15, 2026 in Daytona Beach, Florida. (Chris Graythen/Getty Images)

Reddick was behind Michael McDowell and Carson Hocevar when the final lap started. Hocevar was trying to hold off the pack, but Erik Jones got into the back of him going into Turn 1. McDowell was caught up in the wreck and the drivers fell off the pace.

But no caution flag was flying. Reddick had to avoid the carnage in front of him even as William Byron bounced off him. Ricky Stenhouse Jr. had the lead for a split second, but Chase Elliott took over down the backstretch.

Elliott was vying with Zane Smith as they entered the final turns. Reddick was behind them and Riley Herbst was in fourth place. Reddick went high and got around Smith. He then knifed his way to the bottom to get around Elliott.

As the group got to the finish line, Herbst ran into Brad Keselowski causing both of them to crash. Elliott and Joey Logano were both caught up in the wreck and it was Reddick who came away unscathed.

Riley Herbst, (35), Justin Allgaier, (40), Todd Gilliland, (34), John Hunter Nemechek, (42) and Ryan Blaney, (12) collide during the NASCAR Daytona 500 auto race at Daytona International Speedway, Sunday, Feb. 15, 2026, in Daytona Beach, Florida. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

DAYTONA 500 WINNER REFLECTS ON NASCAR’S TIGHT-KNIT FAMILY AMID RECENT TRAGEDIES IN SPORT

It’s a great way to start the season for Reddick. He finished ninth in the Cup Series standings last season and making the Championship Four in 2024.

The crash-filled final lap was far from the only action.

A caution came out on Lap 192 when Denny Hamlin got poked in the back, hit Christopher Bell and then slammed into the wall. Bell suffered right front tire damage and it cost him the rest of his race.

A massive wreck late in Stage 2 took out a handful of drivers. Hamlin and Justin Allgaier made contact on the frontstretch leading to more than a dozen cars spinning and sliding out of control. Kyle Larson, Austin Cindric, Ryan Blaney, Joey Logano and William Byron were among those involved.

It was the second major wreck of the stage.

Earlier, Chase Briscoe and NASCAR Cup Series rookie Connor Zilisch were involved in a big wreck on Lap 85. Zilisch got loose in Turn 4 and caused a chain reaction. Cody Ware, Ty Gibbs and Austin Dillon were caught up in the accident.

Bubba Wallace was in first place at the end of Stage 2 and Zane Smith was the leader at the end of Stage 1.

Austin Dillon, (3) and Chase Briscoe, (19) collide during the NASCAR Daytona 500 auto race at Daytona International Speedway, Sunday, Feb. 15, 2026, in Daytona Beach, Florida. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE FOX NEWS APP

Reddick, Stenhouse, Logano, Elliott and Keselowski rounded out the top five. Smith, Chris Buescher, Herbst, Josh Berry and Wallace finished in the top 10. Larson, the reigning champion, was 16th.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

Sports

LeBron James enjoys All-Star Game collaboration, says he’s still unsure about his future

Lakers star LeBron James eased his way to the interview podium Sunday with a giant water jug in his hand and a do-rag covering his hair, the last of the NBA All-Stars to speak with the media.

James was selected as a reserve, breaking his NBA record of 21 consecutive starts but extending his record for most appearances to 22.

At 41 and playing in his record 23rd season, James was asked about his future, because his eventual retirement always seems to be a source of curiosity.

So, James was asked before he played in the “U.S. vs. “World” All-Star Game tournament at Intuit Dome whether he had any inkling about what he wants to do next season.

“I want to live,” James said. “When I know, you guys will know. I don’t know. I have no idea. I just want to live. That’s all.”

James played on Team Stripes, joining fellow veterans Kevin Durant and Stephen Curry, who didn’t play because of a right knee injury.

They are long-time combatants, friends and U.S. Olympic teammates. And they are All-Stars again, all older than 37 and still playing at a high level.

“It’s always an honor to see those guys,” James said. “We have had such an unbelievable journey throughout our individual careers and then intersecting at certain points in our careers, matchups in the regular season, Finals appearances, postseason appearances, then Olympics two summers ago. When it comes to me, Steph and KD, we’ll be interlocked for the rest of our careers, for sure. It’s been great to be able to have some moments with those guys, versus those guys, teaming up with those guys.”

The All-Star format has changed from East versus West to U.S. versus the World.

Team Stars forward Scottie Barnes, left, celebrates with Cade Cunningham after hitting a three to beat Team World in the first matchup of the All-Star Game tournament Sunday at Intuit Dome.

(Jae C. Hong / Associated Press)

There were three teams — Team Stars, Team Stripes and Team World, and they played 12-minute games in a round-robin tournament.

Game 1 was Team World vs. Team Stars, a game that went into overtime after Anthony Edwards tied the score 32-32 at the end of the first 12 minutes.

Team Stars, the first team to score five points in overtime, won 37-35 on a Scottie Barnes three-pointer,.

Victor Wembanyama led Team World with 14 points, six rebounds and three blocks.

Anthony Edwards had 13 points for Team Stars, which will play Team Stripes next.

James and Clippers star Kawhi Leonard are on the USA Stripes and Lakers superstar Luka Doncic, the leading all-star vote getter, is on Team World because he is from Slovenia.

James was asked whether he could have ever imagined a USA versus the World all-star format.

“No,” James said, laughing. “No. I mean, East-West is definitely, it’s a tradition. It’s been really good. Obviously, I like the East and West format. But they are trying something. But we’ll see what happens. I mean, it’s the US versus the World. The World is gigantic over the U.S. So, I’m just trying to figure out how that makes sense. But, I don’t want to dive too much into that. Yeah, East-West is great. We’ll see what happens with this.”

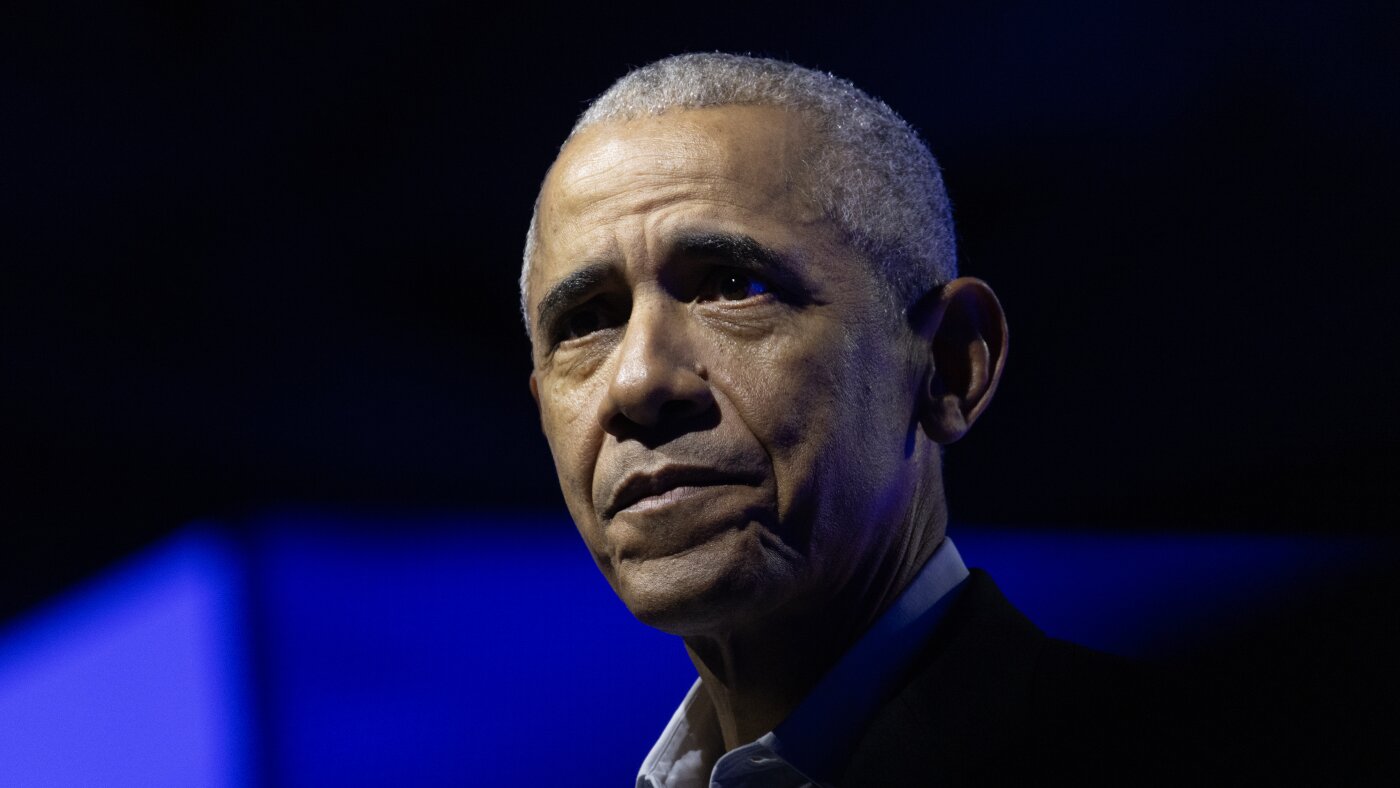

Just before the tipoff of the first game, former President Barack Obama and former First Lady Michelle Obama were introduced to a standing ovation.

Sports

Olympic hockey fans raise Greenland’s flag during USA’s dominant win over Denmark, sparking viral reaction

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

During Team USA’s comeback men’s hockey win over Denmark at the Winter Olympics, two fans raised the flag of Greenland in the stands to protest President Donald Trump’s intent to acquire Greenland for the U.S.

The flag was raised enthusiastically after Denmark took an early lead. However, the U.S. came back to win the game 6-3.

Vita Kalniņa and her husband Alexander Kalniņš, fans of the Latvian hockey team who live in Germany, held up a large Greenland flag during warmups and again when the Danish team scored the opening goal of the preliminary round game against the U.S., which ultimately beat Denmark 6-3.

The United States’ Brady Tkachuk, right, challenges Denmark’s Oliver Bjorkstrand during a preliminary round match of men’s ice hockey at the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan, Italy, Saturday, Feb. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Petr David Josek)

“We are Europeans, and I think as Europeans we must hold together,” Kalniņš told The Associated Press.

“The Greenlandic people decide what will happen with Greenland, but, as it is now, Greenland is a part of the Danish kingdom and, as Greenland is a part of Denmark, as in this case, we support both countries against the U.S.”

A Danish fan at the game, Dennis Petersen, said, “It doesn’t matter whatever sport it is — it could be tennis, it could be bobsledding, it can be ice hockey, it could be football — it has nothing to do with politics. … They are athletes, not politicians.”

An American fan at the game, Rem de Rohan, said, “I think this is the time for people to kind of put that down and compete country versus country and enjoy,” he said. “We love rooting on every country that’s been here.”

Fans on social media had their own reactions to the flag display and the result of the game.

“Now that the USA is up 4-2 could we place a wager that if the USA wins the game, Denmark gives up Greenland?” one fan wrote in response to the flag.

One fan wrote, “Team USA won, do we get Greenland now?”

AMERICANS ATTENDING OLYMPICS URGED TO ‘EXERCISE CAUTION’ AFTER ITALIAN RAILWAYS HIT BY SUSPECTED ‘SABOTAGE’

The United States’ Jack Eichel, second right, celebrates after scoring his team’s third goal during a preliminary round match of men’s ice hockey against Denmark at the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan, Italy, Saturday, Feb. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Petr David Josek)

Another fan similarly said, “How did that turn out? we won, we get greenland now.”

Some American conservative influencers used the U.S. victory as a springboard to make viral jokes about annexing Greenland.

The comeback victory by the U.S. appeared uncertain early in the game.

After trailing 2-1 through the first period, the Americans dominated on offense to take a 6-3 victory over Denmark Saturday in the Milan Cortina Olympic Games.

The Americans scored three unanswered goals to open the second period, with 4 Nations hero Brady Tkachuk (Ottawa Senators), Jack Eichel (Vegas Golden Knights) and Noah Hanifin (Vegas Golden Knights) finding the back of the net.

Both sets of brothers on the team — Brady and Matthew Tkachuk and Jack and Quinn Hughes — each had a point in the contest. Fourteen players had points for the Americans with a different goal scorer each time the lamp was lit.

The Americans had 47 shots on goal compared to Denmark’s 21.

The U.S. ends preliminary play Sunday with a game against Germany at 3:10 p.m. ET. The Americans will once again be heavy favorites, and a victory will put them into the knockout stage.

The Americans can also go right to the knockout stage with an overtime loss. With a regulation loss, their fate would be determined by Canada’s game against France and point differentials with Slovakia, Finland and Sweden.

But as a heavy favorite against a German team with just eight NHL players, the U.S. may not need to worry.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter

-

Alabama1 week ago

Alabama1 week agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoVideo: Farewell, Pocket Books

-

Illinois7 days ago

Illinois7 days ago2026 IHSA Illinois Wrestling State Finals Schedule And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoApple might let you use ChatGPT from CarPlay

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHegseth says US strikes force some cartel leaders to halt drug operations

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘Regime change in Iran should come from within,’ former Israel PM says

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoWith Love Movie Review: A romcom with likeable leads and plenty of charm

-

News1 week ago

Hate them or not, Patriots fans want the glory back in Super Bowl LX