Mississippi

Mississippi River Centers Inaugural Wakpa Triennial Art Festival In Minnesota’s Twin Cities

Aerial view of downtown Minneapolis over the Mississippi River.

“Wakpa” is Dakota for “river.”

Even before the Dakota were on this land, there was the river. Many rivers, but one superior to all others: Ȟaȟáwakpa. White people called it the Mississippi River.

The inaugural Wakpa Triennial Art Festival takes place June 24 through September 16, 2023, throughout Minnesota’s Twin Cities, the state capital of St. Paul side-by-side with its big brother Minneapolis. Ȟaȟáwakpa winds through them both.

The river makes as good a place as any to start thinking about the event.

The father of rivers shares a story common across the continent with thousands of its offspring. Native people used these waterways to participate in vast trade networks. European traders tapped into them upon arrival. As the colonizers steadily pushed Indigenous inhabitants off their land, the rivers were increasingly used for industry.

They were dammed and dredged and diked to scale up shipping and textile production and power generation. Their natural cycles of flooding were halted by white men. Concrete barriers went up. Their banks were straightened. Adjacent wetlands were pumped dry.

America’s rivers then became toilets, early residents piping their waste directly to the banks and later, civil engineers directing sewage overflow their way during times of heavy rain. Trillions of gallons of herbicide and pesticides flowed into them from farms and lawns. Toxic industrial waste. “Dilution is the solution to pollution,” the operative phrase for industry.

Once a paradise for fish and birds and plants, the country’s rivers nearly died. Riverfront land was often the least valuable and least attractive in cities across America through the 20th century.

It wasn’t until the last 25 or 30 years that the value of rivers for people, not products, began to be understood and appreciated by places fortunate enough to be blessed with a river.

“I grew up here and the river used to stink like a sewer,” Colleen Sheehy, Executive Director of Public Art Saint Paul and the Project Director of Wakpa Triennial Art Festival, told Forbes.com. “It’s taken decades for us to turn back to the river. There’s a lot about the river that not only people coming from outside the Twin Cities, but people here I think will discover.”

Artist, boat builder, fisherman, former professor, clean water activist and Twin Cities native Seitu Jones is aiding in the discovery. His Wakpa Triennial project, artARK, will provide opportunity for more intimate acquaintance with the river. The 20-foot-long wooden and aluminum pontoon boat will serve as something of a research vessel with an artist/naturalist as part of the crew.

ArtARK will use art and ecology to foster a greater understanding of the Mississippi River watershed and residents’ role as river stewards.

“I live two miles away from the river, one of the greatest rivers in the world, and many folks–my neighbors–will pass over the river three or four times in a day, but nobody ever gets to the river’s edge,” Jones told Forbes.com.

When the project is completed later this summer, the public will have the opportunity to tour the Mississippi River aboard the artARK. The experience will be participatory as guests can help interpret and present scientific data including pH and oxygen levels, temperature, turbidity, clarity, salinity, and observations of invertebrates, fish, birds and mammals through writing, visual art, and performance with the help of the vessel’s artist/naturalist.

“There’s been much more attention placed (on the river) as this recreational and environmental and inspirational resource (in recent years),” Jones adds.

Instead of using and abusing the Mississippi River, the Twin Cities are increasingly caring for and restoring it. A river once working for industry, is now working for people.

Sewage is being treated before making its way to the river. New public parks are bringing people to the river’s edge. The once-radical possibility of removing the river’s locks and dams through town are being considered, part of a national trend returning health to riverine ecosystems and the people who live by them.

“The river going through St. Paul is stunning; there are beautiful limestone cliffs and bluffs along the river in the downtown–it’s spectacular,” Sheehy said.

Sean Sherman’s (Oglala Lakota) Owámni restaurant overlooks the river by St. Anthony falls in St. Paul. Sherman, “The Sioux Chef,” was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people for 2023 due to his ongoing efforts promoting Indigenous food ways.

Reservations at the restaurant are extremely hard to come by, planning should be made months in advance. While waiting for a table, enjoy views of the river, thankfully, now, without the sewer smell.

A Thriving Arts Community

A view of downtown St. Paul in the morning with still water from the Mississippi River with … [+]

The Wakpa Triennial will feature over 40 public events and programs, community-based performances, and temporary public art installations throughout the metro area. Most will be free to attend. In addition to sites along the river and in parks, new commissions will be found in galleries, museums, and alternative spaces indoors and out.

Why now?

Sheehy believes the Twin Cities’ arts community has finally grown to a level where it can support an event of this ambition.

“I’m old enough to have seen (the Twin Cities’ art scene) develop from the major institutions to this wonderful density of small organizations that are connected to communities and neighborhoods and specific artistic disciplines,” Sheehy explained. That development extends to artists. “From being a place where a lot of artists would move away to pursue careers in New York, L.A., and now we’re a place where artists are thriving.”

Wakpa also furthers a national and global trend.

“These kinds of biennials and triennials have been increasing as efforts to lift up an art scene (and) create exciting new work that gets people out traversing a city, learning more about the city,” Sheehy said.

Discovery is a major goal for Wakpa.

“When I’ve gone to these kinds of art festivals in other cities, they’ve been a beautiful way of learning a city because typically, if I traveled to another city, I’ll go to the big museums, but I don’t necessarily get into the neighborhoods,” Sheehy said.

You are on Native Land

St. Paul and Mississippi River in Minnesota

Minnesota, along with parts of South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska and Canada are the ancestral homelands to the Dakota people. Scandinavians found it in the late 19th century. They were given free land taken from the Dakota to farm and homestead.

Minnesota is still often associated with these Nordic immigrants–look at the Minnesota Vikings football helmet. More residents of Norwegian and Swedish ancestry continue living there than any other state.

But St. Paul also has the largest Hmong community in an urban area in the United States. Minneapolis has the largest Somali population outside of Mogadishu.

In the 1950s, 60s and 70s, a federal program known as the Indian Relocation Act incentivized tens of thousands of Native people from across America to leave their reservations and move to cities for greater economic opportunity. It was another government effort to disassociate Native people from their land and culture under the guise of “progress,” and Minneapolis was a major relocation hub.

To this day, it has one of the largest Native populations of any American city.

“There are these cultural communities that people can experience and help to dispel the idea that we’re this all-white German Scandinavian area,” Sheehy said. “There’s a lot of diversity that is adding so much to our understanding, our experiences of city and art and food and customs.”

The Wakpa name was selected only after consultation with Dakota leaders and artists.

Of the more than 100 Minnesota-based artists contributing to the festival, a majority are people of color.

Organizational partners include Wakan Tipi Center which honors sacred Dakota sites in the area, Oyate Hotanin, an Indigenous arts organization, the Asian Economic Development Association, Center for Hmong Arts and Talent, the contemporary Native American art gallery All My Relations Gallery and the Hmongtown Marketplace.

And the Philando Castile Peace Garden.

Philando Castile and George Floyd and Duante Wright…

A general view is seen of the burned and destroyed Third Police Precinct on March 11, 2021 in … [+]

George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis, not Mississippi. The Twin Cities prides itself on being one of the most progressive and educated communities in America, yet, police murder has been the area’s defining attribute since Floyd’s death was witnessed worldwide.

It wasn’t an isolated incident. Cops in the Twin Cities have an outrageous record of unwarranted violence against minorities.

Philando Castile was a young Black man shot and killed by police in the metro area in 2016. The longtime employee of the St. Paul Public School System perished sitting in his car after being pulled over for a broken taillight.

Minneapolis police rampaged in the days after Floyd’s murder. They were heard on their own body cam footage enjoying “hunting” peaceful protestors.

Like Castile, Duante Wright was a young Black man killed by police while sitting in his car after being pulled over in suburban Minneapolis for a traffic stop. His death occurred during the trial of Floyd’s murderers in 2021.

A damning report from the Department of Justice released on June 16, 2023, found the Minneapolis Police Department for years has engaged in a pattern of excessive force and racial bias among other civil rights abuses.

“We’re still struggling to recover and rebuild,” Sheehy said of the demonstrations following Floyd’s murder. “Not only physically rebuild, but to rebuild what future we want here that’s based on equity and inclusion, and to address these sadly persistent disparity gaps that exist in the Twin Cities, and in Minnesota, between white communities and communities of color.”

Wakpa Triennial leans in, placing these conversations and sites front and center.

“One node of the triennial in Minneapolis is around Minnehaha and Lake Street, it’s called the Longfellow neighborhood, it’s the location of the third precinct building that was burned, that was the focus of a lot of demonstrations. That’s the precinct Derek Chauvin worked at,” Sheehy explains.

Chauvin is the officer who choked Floyd to death.

“The building wasn’t burned to the ground, but it’s standing empty with a fence around it for these three years,” Sheehy said. “There’s a lot of rethinking and rebuilding in that node because there were a number of important small cultural businesses and organizations whose buildings burned and it’s an opportunity to come to that neighborhood, think about what happened there, and learn more about how the neighborhood is rebuilding.”

Artists and the arts community will be key to that effort.

Rebuilding a community following Floyd’s murder, and Wright’s, and Castillo’s.

And rehonoring Native homelands.

And restoring a river.

Mississippi

As Climate Threats to Agriculture Mount, Could the Mississippi River Delta Be the Next California? – Inside Climate News

This story was originally published by The Tennessee Lookout.

A smorgasbord of bright red tomatoes and vibrant vegetables line the walls of Michael Katrutsa’s produce shop in rural Camden, Tennessee. What began a decade ago as a roadside farm stand is now an air-conditioned outbuilding packed with crates of watermelon, cantaloupe and his locally renowned sweet corn — all picked fresh by a handful of local employees each morning.

The roughly 20-acre farm west of the Tennessee River sells about half of its produce through his shop, with the rest going to the wholesale market.

Farms like Katrutsa’s make up just a sliver of roughly 10.7 million acres of Tennessee farmland largely dominated by hay, soybeans, corn and cotton. Specialized machines help farmers harvest vast quantities of these commodity “row crops,” but Katrutsa said the startup cost was too steep for him. While specialty crops like produce are more labor-intensive, requiring near-constant attention from early July up until the first frost in October, Katrutsa said he takes pride in feeding his neighbors.

The World Wildlife Fund sees farms in the mid-Mississippi delta as ripe with opportunity to become a new mecca for commercial-scale American produce. California currently grows nearly three-quarters of the nation’s fruits and nuts and more than a third of its vegetables.

Explore the latest news about what’s at stake for the climate during this election season.

But as climate change compounds the threats of water scarcity, extreme weather and wildfires on California’s resources, WWF’s Markets Institute is exploring what it would take for farmers in West Tennessee, Mississippi and Arkansas to embrace — and equitably profit from — specialty crop production like strawberries, lettuce or walnuts.

Specialty crops make up only 0.19% of the region’s farm acreage, but their higher sale value allows them to generate 1.08% of the region’s agriculture revenue, according to WWF’s May report, called The Next California, spearheaded by Markets Institute Senior Director Julia Kurnik. She argues that there’s an opportunity to proactively create more inclusive, higher-yield business models on existing farms, preventing natural ecosystems from being unnecessarily transformed into farmland.

But shifting produce growth to the Mid-Delta comes with hurdles: it requires buyers willing to try new markets, understanding of new crops’ diseases and needs, specialized equipment like cold storage and lots of expensive hands-on labor.

“It is not as simple as a farmer simply putting new crops in the ground,” Kurnik said.

Early Adopters Put Idea to the Test

Sixth-generation Arkansas farmer Hallie Shoffner is putting WWF’s models to the test through a nonprofit called the Delta Harvest Food Hub. The hub works with Black and women farmers to pilot the scalability of growing specialty crops in the Delta region, starting with specialty rice.

Shoffner grows basmati, jasmine, sushi rice, sake rice seeds and more on her 2,000-acre, century-old farm located in an unincorporated town outside Newport, Arkansas. She’s skeptical about a full switch to produce, but sees specialty rice products as “low-hanging fruit” easily adopted in the mid-Delta, where commodity rice is already widely grown.

The United States is the fifth-largest rice exporter in the world, and Arkansas is the country’s top producer, with other Mississippi River valley states not far behind. But the majority of specialty rice is grown in California or imported from East Asian countries.

“We are forward-thinking farmers who want to change, who want to do something different,” Shoffner said. “We want to make more money, because we know we cannot make as much money as small farms in the current agricultural economy.”

The commodity farming that dominates Delta agriculture makes the economic success of farmers largely dependent on the market prices of rice, corn, soybeans, wheat and other crops, Shoffner said. This incentivizes farms to grow larger to ensure they turn a profit even when prices are low, like they are now. But smaller farms struggle to stay afloat.

Shoffner said her vision for developing specialty crop markets in Arkansas will be through more collaboration between many smaller farms to diversify crop production and produce for large contracts together. She’s also exploring possibilities for expanding chickpea, sunflower, sesame and pea production in Arkansas.

And while she’s at it, Shoffner is working to make agriculture more equitable.

“As a white farmer who is a sixth generation farmer, I realize that I have inherited a large amount of land that systematically disenfranchised Black farmers,” Shoffner said. “And it is my responsibility to acknowledge that, and leverage what I’ve been given to help others.”

Her project, Delta Harvest, has a contract to grow specialty rice with a large company and she’s working with several Black farmers. She was too small to do it by herself, so they are doing it cooperatively.

Finding the Right Markets

In Mississippi, efforts to shift some of California’s sprawling specialty crop industry to the Mid-Delta drew skepticism from some farmers—even those with established specialty crop operations.

For the past 20 years, Don van de Werken has co-owned a 120-acre blueberry and tea farm in Poplarville, Mississippi, distributing much of its crops to buyers in his county and nearby cities.

Van de Werken questioned whether there would be enough regional demand to sustain a scaled-up specialty crop industry in Mississippi, noting that the success of his own enterprise hinges on targeting hyper-local markets like New Orleans. Shipping vegetables, fruits and other produce to buyers outside the Delta region would quickly become cost prohibitive for local farmers, van de Werken said.

“The problem we have, not just in Mississippi but the mid South in general, is we just don’t have the population base,” said van de Werken, who is also president of the Gulf South Blueberry Growers Association. “We don’t want our blueberries to go to Maine or Seattle. We want to focus our produce in a regional market.”

To make growing specialty crops worthwhile, Mississippi farmers would need to identify nearby buyers willing to purchase the new products on a consistent basis, van de Werken said. While selling goods directly to retail grocery chains like Kroger is often difficult, farmers could reduce financial risks by signing purchasing agreements with regional brokers like Louisiana-based Capitol City Produce.

“Anybody that puts anything in the ground is already taking a risk, but you want to minimize that risk,” he explained. “If you can prove to the brokers and the buyers that they can make money doing this, then the farming will come.”

The WWF report investigates ways to distribute risk across the supply chain to make selling to new markets easier on farmers, and works to connect buyers with Mid-Delta farmers.

AgLaunch, a Memphis-based nonprofit that guides farmers in innovation, estimates that adding specialty crops to the Mid-Delta region could spur $4.6 billion in added revenue and 33,000 jobs. But while commodity crop prices are readily available on the Chicago Board of Trade, the specialty crop market is generally not so transparent. Large, vertically integrated companies usually dictate contract terms, AgLaunch President and farmer Pete Nelson said.

AgLaunch helps build “smart contracts” that allow multiple farmers to produce on a contract, helping them secure higher quantity deals with proper compensation as a collective.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Purdue College of Agriculture professor Fred Whitford said the idea of farming cooperatives that help smaller farmers carve out space in a large-quantity market is more than 100 years old. Whitford compared commodity producers to retail giants like Walmart, which make money by selling in bulk. Small producers are more like Ace Hardware, he said.

“Maybe the smaller folks have an ability to make more off their land by going to a specialty crop,” he said.

New Challenges Need New Solutions

Farmers who embrace specialty crops will face hurdles before they make it to the market.

Growing produce can be more profitable but “easier said than done,” Whitford said. “It’s nice on paper … but boy, in reality, you’re going to have to keep an eye on this crop, whatever you’re growing, because one slip up … then you have lost a lot of money.”

In Tennessee, Katrutsa grew strawberries in addition to his other crops for 10 years, but last April, a hail storm pulverized his entire field, leaving him with nothing. He’s not growing strawberries this year, and he might not plant them again — he’s not sure if he can find enough labor to make it work.

He grows many types of produce so if one fails, it’s less catastrophic. He sources seedlings from a neighboring state (it’s cheaper than growing from seed) and plants five times each season to maximize yield.

He works with a consultant to help identify diseases and how to treat them. Tomatoes are the most challenging, Katrutsa said. Some of his tomato plants withered this year due to bacterial wilt that flourishes in wet soil and high temperatures and has few effective chemical remedies.

Carolyn Preble helps out farmer Michael Katrutsa at the farm shop, which stocks the more than 20 acres of produce Katrutsa grows in rural Camden, Tennessee. Credit: John Partipilo/Tennessee Lookout

Chemical treatments pose other challenges. In Shaw, Mississippi, Michael Muzzi relies on a range of herbicides to grow soybeans and other feed grains on his 2,000-acre farm. Once sprayed, herbicides like Liberty and Dicamba remain in the ground and can drift in the air, which is hazardous to specialty crops, like tomatoes, that aren’t resistant.

“You’re not going to be able to spray [those herbicides] on specialty crops,” Muzzi said. “You’d have to have something that’s chemically tolerant.”

Growing fruits and vegetables on a farm with previous heavy herbicide use would require insulating those crops from chemical runoff — a feat that could only be reliably achieved by leaving whole acres of land unused for years, he said.

AgLaunch is exploring innovative ways to address these problems. For some farmers, this means helping make their existing row crops more efficient using farmer-incubated technology, adding local value by growing specialty crops or taking on processing, Nelson said.

Then there’s disruption with higher risk: farmers can partner with agriculture automation technology startups, allowing them to field test their products and collect data in exchange for farmer equity in the startup companies. If the startup succeeds, the farmer shares in the benefits.

“It’s not as simple as, ‘Hey, we should grow tomatoes,’” Nelson said. “It’s how you think about the whole value chain and make sure the farmer is protected. Make sure it’s not an opportunity just to grow a crop, but it’s an opportunity to own part of the processing or to build new products.”

Kurnik said WWF isn’t trying to recruit farmers to start growing specialty crops – they just want Mid-Delta farmers to have the information they need to make informed decisions. In terms of acreage, row crops “dwarf” specialty crops in the United States. A small percentage shift would mean a significant change in the level of specialty crops in the Delta.

“We don’t need everyone to want to jump on board tomorrow,” she said. “They would flood the market if they did.”

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri in partnership with Report for America, with major funding from the Walton Family Foundation. Disclosure: The Next California report was also funded by Walton.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,

Mississippi

Mississippi man dies of an apparent overdose in MDOC custody in Rankin County

A 41-year-old man incarcerated at Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Rankin County died Thursday of an apparent overdose.

Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Burl Cain confirmed the death in a news release.

The man was identified as Juan Gonzalez. According to prison records, he was serving a four-year sentence on multiple convictions in Hinds County and was tentatively scheduled for release in May 2025.

“Because of the unknown nature of the substance, the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency and the Mississippi Department of Health were notified,” MDOC reported.

The investigation into Gonzalez’s death remains ongoing.

This is a developing story and may be updated.

Mississippi

Mississippi high school football scores for 2024 MHSAA Week 2

Watch as Clinton begins season with 26-20 win over Warren Central in Vicksburg

Watch highlights from Clinton’s 26-20 win over Warren Central in the Arrows season opener Friday night.

Here is our Mississippi high school football scoreboard, including the second week of the season for MHSAA programs.

THURSDAY

Heidelberg 14, Quitman 8

Independence 20, Byhalia 6

Myrtle 47, Potts Camp 18

North Pontotoc 41, Water Valley 19

Okolona 40, Calhoun City 0

Provine 16, Lanier 6

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEconomic portfolios are key in talks to chose new EU commissioners

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoSaripodhaa Sanivaaram Movie Review Rating

-

News1 week ago

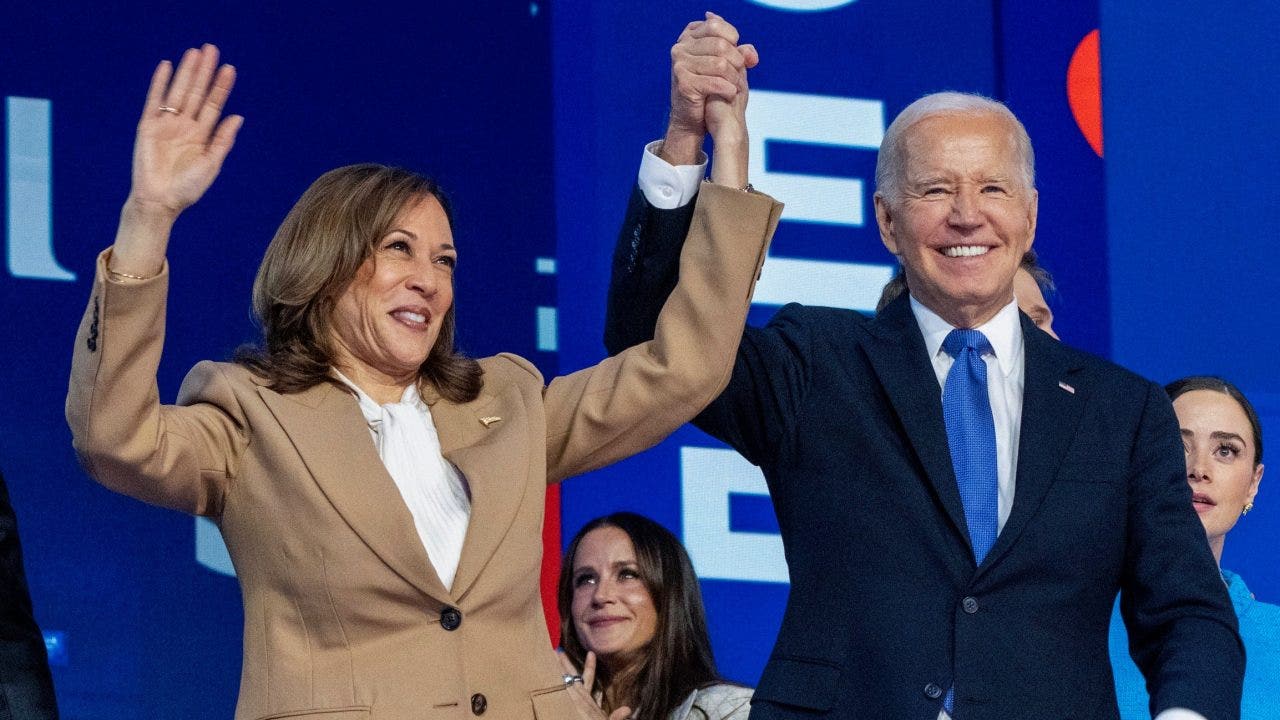

News1 week agoHarris kicks off Georgia tour as Trump posts grievances on social media

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoTrump impersonates Elon Musk talking about rockets: ‘I’m doing a new stainless steel hub’

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBrussels, my love? Is France becoming the sick man of Europe?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoEx-California resident slams state bill that gives illegal immigrants housing loans: 'Asinine'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump campaign slams Harris as 'still a San Francisco radical' after CNN interview

-

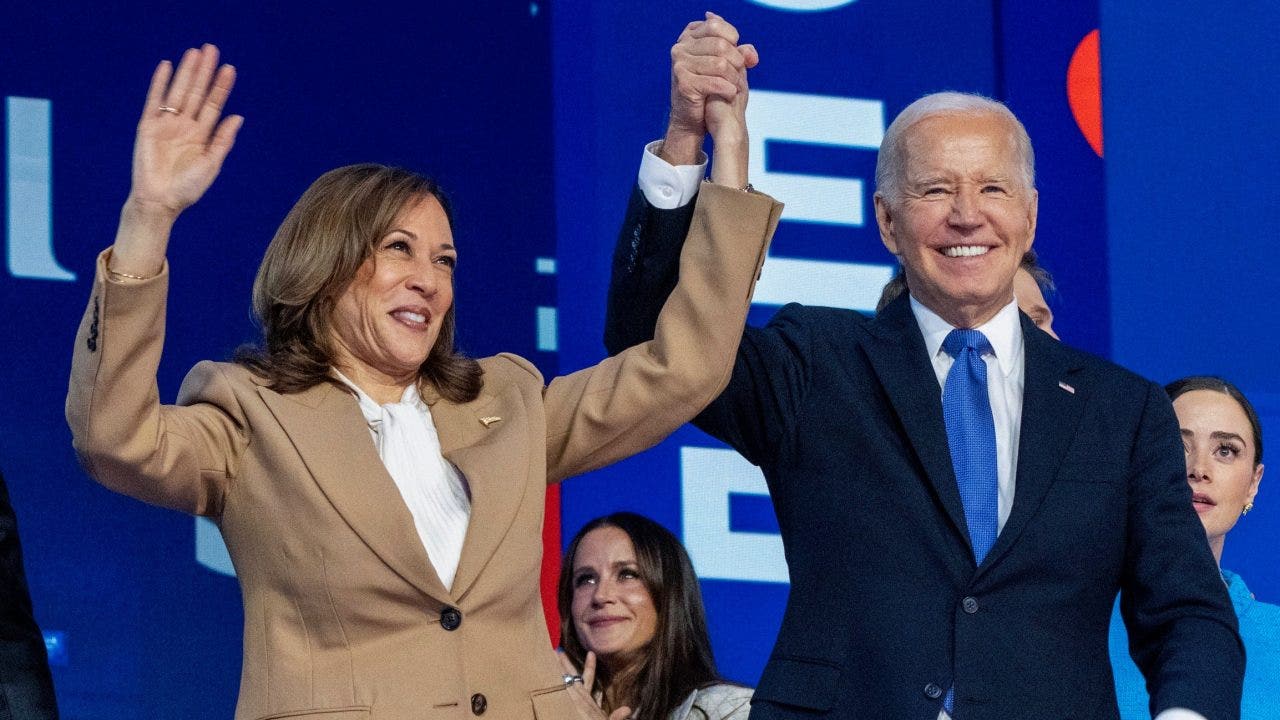

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHarris says no regrets about defending Biden fitness for office

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25607589/SHARE_20240906_0719580.jpeg)