Science

‘Marte es un planeta, pero no sabemos cómo funciona’: la NASA quiere un laboratorio para evitar una plaga marciana

Lo mejor que pudo hacer el Tiger Crew RAMA fue observar qué han hecho las instalaciones con funciones de contención y limpieza para mantenerse así y no perder la esperanza de lograr combinarlas de la mejor manera posible.

En de los laboratorios BSL-4 que visitó el equipo, siempre había filtros absolutos, o HEPA, por su sigla en inglés. El equipo también se informó sobre las prácticas de esterilización, como el baño de instrumentos en peróxido de hidrógeno en fase de vapor, que mata los contaminantes de una superficie. Todavía hacen falta más investigaciones con el fin de identificar la mejor opción para esterilizar el materials extraterrestre. “Ya se están realizando investigaciones para saber cómo ocurre la descontaminación en el contexto de estas muestras”, explicó Harrington.

En términos de estructura, la instalación de recepción de muestras podría tener pisos, techos y paredes recubiertas con epoxi, como a veces sucede con los laboratorios BSL-4 y las salas limpias. La habitación prístina donde los científicos construyeron el rover europeo en Marte, por el contrario, tenía paredes hechas de acero inoxidable soldado, un materials que también fue aprobado para la infraestructura de las instalaciones BSL-4. Ambos materiales podrían funcionar para los propósitos de la NASA.

El Tiger Crew RAMA también investigó los instrumentos que los científicos podrían usar para manipular muestras marcianas: microscopios, cajas de guantes y robótica como “micromanipuladores” que permiten a los investigadores manipular materiales con precisión y sin tener que tocar las muestras con las manos. Los científicos estudiaron de forma remota sustancias en entornos de nitrógeno puro, para evitar degradarlas, algo que la NASA también tendrá que hacer.

Pero han surgido problemas en los detalles, mostrando lo que no funcionaría bien para la NASA. Muchos de los laboratorios existentes tenían menos de 92 metros cuadrados, por lo que son demasiado pequeños para la escala que requiere la misión. Los umbrales elevados o las puertas estrechas dificultaban la entrada y salida del equipo. Y los laboratorios BSL-4 existentes son como el Lodge California de las bioinstalaciones: lo que entra normalmente no sale, al menos no sin una descontaminación extensa y, en ocasiones, destructiva. Por lo basic tienen menos instrumentación que la que tendría un laboratorio regular. Y parte del objetivo de Mars Pattern Return es poder aprovechar los dispositivos científicos sofisticados.

Al ultimate, el equipo le presentó a la NASA unas cuantas posibilidades para las instalaciones de recepción de muestras de Marte: la agencia podría modificar un laboratorio BSL-4 existente para lograr que sea impoluto. Otra opción que tal vez requiera más tiempo y dinero es que se construyan instalaciones nuevas de ladrillo y mortero desde cero, con un diseño específico para este efecto. La NASA también estudia opciones intermedias, como construir un espacio más barato, modular y de máxima contención y envolverlo en un edificio más rígido.

Science

Q&A: Parent burnout is real. Here's what you can do about it

It’s been several years since kids returned to their classrooms and workers went back to their offices. We dine indoors at restaurants and don’t hesitate to board a plane for a family trip.

COVID-19 isn’t disrupting our lives like it did in the days of lockdowns, social distancing and mandatory masking. So why are so many parents still struggling like it’s the height of the pandemic?

A report released Wednesday by researchers at the Ohio State University College of Nursing sums it up in two words: parental burnout.

“When the pressures of parenting lead to chronic stress and exhaustion that overwhelm a parent’s ability to cope and function, it is called parental burnout,” the report explains. This condition leaves moms and dads “feeling physically, mentally and emotionally exhausted, as well as often detached from their children.”

In a survey of 722 working parents conducted in June and July 2023, 57% reported symptoms indicative of this modern-day malady. That’s only a small improvement from the early months of 2021, when 66% of parents surveyed were described as burned out.

Report authors Kate Gawlik, a family nurse practitioner, and Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, the university’s vice president of health promotion and its chief wellness officer, found that people struggling with parental burnout were straining to live up to unrealistic expectations. They felt judged by family and friends if they hadn’t steered their children onto the honor roll and an all-star sports team while planning a picturesque vacation and keeping their homes neat and tidy.

Bernadette Melnyk, left, and Kate Gawlik led a study that reveals how expectations to be the perfect parent contribute to burnout, stress, anxiety and depression among working parents.

(Ohio State University)

Those are the wrong goals, Gawlik and Melnyk said.

The survey found that the more extracurricular activities a child was involved in, the more likely he or she was to have trouble with concentration, get into fights with other kids, have low self-esteem and exhibit other behaviors that can lead to poor mental health.

However, those risk factors became less likely when children had more time for unstructured play and spent more quality time with their parents.

Not only is there no such thing as a perfect parent, but also, the more you try to be one, the more your efforts will backfire, Gawlik and Melnyk said. They spoke with The Times about what they’ve learned about parental burnout and how to overcome it.

What prompted you to study parental burnout?

Kate Gawlik: We really got interested in this idea of parental burnout during the pandemic. When it started, I had four children, and my oldest was in second grade. I was trying to work and be a parent and home-school and everything. I just had this constant feeling of having to do everything all the time.

I had heard the term “burnout,” but I never really related it to parenting. One day I heard the term “parental burnout” and I was like, that’s what I’m feeling. It’s not like depression, it’s not like anxiety. It’s this very focused burned-out feeling related to being a parent and having to do everything.

We’re in a much better place than we were back then. Does that mean parental burnout is better too?

Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk: People assumed that once the pandemic was over, things would just automatically improve. Our current study shows that’s really not the case. People didn’t just bounce back like a lot of people thought they would.

Gawlik: That’s why we wanted to study this again now. We don’t have the same stressors we had before. We wanted to look at what the stressors are now.

And what are they?

Gawlik: I feel like parents now are trying to make up for everything they lost, or felt they lost, during the pandemic.

We have really latched onto this culture of achievement. I see that and I feel that every day. Parents feel this continual pressure to keep up with everybody else. If their kids aren’t in honors classes, they need to get them tutoring so that they are. If they’re not the best at sports, they need to be putting them in even more practices.

It’s this continual cycle of more, more, more, more. How can you not feel burned out?

It’s this continual cycle of more more more more. How can you not feel burned out?

— Kate Gawlik

Melnyk: If a parent feels they’re a good parent, there’s not as much burnout and mental health issues. But if they aren’t feeling good about their parenting, there’s more burnout, more depression, and the kids have more issues. So the self-judgment piece is really key.

What makes someone prone to parental burnout?

Gawlik: Social media is very powerful, and very parent-shaming. A parent can look at social media and be like, “They look like they’re doing everything and they’re so happy and their house doesn’t seem chaotic at all. What’s wrong with mine?”

Melnyk: This whole “perfect parent” image that so many people strive for — it’s really important that parents know there’s no such thing.

Were you surprised to find that parental burnout was still so prevalent?

Melnyk: It was right about where we expected it to be. The pandemic didn’t resolve and then everybody gets back to normal. It takes time.

Were there other findings that did surprise you?

Gawlik: One of the things that I think was so striking was the relationship between child mental health and the number of extracurricular activities that children participate in. This is a great example where maybe as a parent you’re like, “OK, you can get back into sports, you can do everything.” But it’s almost to the detriment because we know that kids need time just to play.

Kids’ work is to play, and they’re not getting to do that. We’re robbing them of those opportunities because of all this structure. It’s all good intentions — we’re doing it to help our children — but the results of our study show that’s not where we need to be putting our time and focus.

Does burnout at work contribute to burnout at home?

Gawlik: When you’re with your kids, you’re always thinking about the things you need to get done at work. And then when you’re working, you’re always thinking about how you need to help your children. So you’re constantly in this state of turmoil, where you’re feeling this tug from both areas.

Melnyk: Honestly, in all likelihood, if you’re a working parent with children — especially if they have mental health needs — you’re not going to have work-life balance most of the time. That’s another unrealistic expectation.

In your report, you talk about ‘positive parenting.’ What is that?

Gawlik: The goal with positive parenting is building a relationship with your child. A lot of times we miss that relationship piece, or we put it second to what others are expecting of us.

For instance, everyone got very attached to our electronics during the pandemic. We were attached before, but this was on a whole new level because everything now was via Zoom, or via your phone. What that says to a kid is, “My parent is working. My parent is on their phone. I am a second-class citizen to that.” You have to think about how that makes a child feel.

What can parents do to overcome their burnout?

Melnyk: Quality playtime with your kids is so key. Not just being with them and listening with one ear and working on something else at the same time. It doesn’t have to be hours at a time. Whether it’s 10 minutes or 20 minutes, to give your child undivided attention is worth its weight in gold.

Adults need time to still do the things that bring them meaning and joy. If you’re not making time for them, you’re going to burn out much faster. Parents do a great job taking care of everybody else, but they often don’t focus on their own self-care. You can’t pour from an empty cup, and that’s what a lot of parents are trying to do.

If a parent is feeling stressed and overwhelmed, the idea of making a change may seem even more stressful and overwhelming. How do you break the cycle?

Gawlik: That can be tricky. When you get into this cycle of burnout — even a cycle of feeling like you’re not a good parent — it can be really hard to break out of it. You’re going to have to make an effort.

When you feel like you can’t literally put one more thing on, that’s when it comes back to shifting your priorities. What can you give up to make the mental capacity to do it? It’s going to look different for every parent.

My house is a mess 90% of the time and I’m not feeling bad about it anymore. I’ve just tried to reframe it. My kids are creative. Our toys are all over because the kids are playing with them and not sitting in front of a screen. I’m OK with the fact that my house is not clean all the time now because I can’t do that along with everything else that I’m doing and feel like I’m successful.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Science

Bill could end holdup for California research on psychedelics and addiction treatment

California lawmakers could soon clear a governmental logjam that has held up dozens of studies related to addiction treatment, psychedelics or other federally restricted drugs.

The holdup revolves around the Research Advisory Panel of California, established decades ago to vet studies involving cannabis, hallucinogens and treatments for “abuse of controlled substances.”

It has been a critical hurdle for California researchers exploring possible uses of psychedelics or seeking new ways to combat addiction. Scientists cannot move forward with such research projects without the panel’s blessing.

The panel had long met behind closed doors to make its decisions, but concerns arose last year that it was supposed to fall under the Bagley-Keene Act, a state law requiring open meetings. Holding those meetings in public, however, raised alarm about exposing trade secrets and other sensitive information.

So the panel stopped meeting at all. It has not convened since August. Meetings ordinarily scheduled for every other month have been canceled since October.

The result has been a ballooning backlog: As of early May, there were 42 new studies and 28 amendments to existing projects awaiting approval, according to state officials.

Ziva Cooper, director of the UCLA Center for Cannabis and Cannabinoids, said she had submitted one study to the California panel over a year ago — one already approved by the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and an institutional review board. That research will assess the health risks of cannabis for seniors and young adults ages 18 to 25, two groups whose cannabis use has been on the rise, she said. Cooper said the panel sought a small change: adjusting two words in a consent form for study participants. But because the panel has not been meeting, she has been unable to proceed.

The holdup has also snarled two other studies her UCLA center had submitted to the panel — one examining whether cannabis could be used as an alternative to opioids for pain relief, another on whether a psychedelic compound found in mushrooms, psilocybin, could help treat people struggling with cocaine addiction.

And Cooper said she hasn’t even bothered to submit three more studies, including research on the effects of high-potency cannabis. The holdup has left Cooper and other researchers fearing they could lose funding for planned studies or be forced to lay off staff.

The idea of having to study something different because “in California I can’t do the research that I’m trained to do … is demoralizing,” Cooper said. It aggravates her “to not be able to answer the questions that are desperately needed right now” as the range of cannabis products on the market has grown.

The standstill “has broad implications, costing researchers money in expired grants and contingent grants, shortened patents on new drugs, lost wages for research personnel, lost talent, and lost costs of research drugs for human use that will expire before use,” according to an analysis prepared for a state committee.

That long hiatus could soon end: Under Assembly Bill 2841, the state panel would be able to hold closed sessions to discuss studies that involve trade secrets or other proprietary information. The bill, proposed by Assemblymember Marie Waldron (R-Valley Center), would go into effect immediately if signed by the governor.

“We are focused on reactivating the large amount of research studies that have been on hold for over a year now,” Waldron said in a statement. “This is the quick and urgent solution needed to address that problem.”

The bill is supported by the nonprofit Veterans Exploring Treatment Solutions, which supports research into the possible benefits of psychedelics for treating depression and other conditions among military veterans and helps them obtain such treatment abroad.

“Psychedelic research has ground to halt in California — including numerous VA studies, “ said its director of public policy, Khurshid Khoja. If the Legislature does not act swiftly, the state will see “a rapid exodus of skilled researchers from California universities and research institutions to pursue their critically important work elsewhere — not to mention capital flight by funders who’ll deploy research dollars outside the state.”

“AB 2841 is an urgently needed response to address this crisis,” Khoja said.

To many researchers, however, AB 2841 does not go far enough. Dozens of scientists have called for the panel to be eliminated, arguing that even when it was meeting regularly, it was an unnecessary obstruction to research already being scrutinized by other government and institutional reviewers.

In a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom, a coalition of researchers argued that undergoing the state review could delay a study by at least five months, resulting in more than $100,000 in “unnecessary staff expenditures” in that time. Because other states don’t have that hurdle, they argued, California researchers are losing out on competitive funding — and Californians miss chances to participate in local trials for emerging treatments.

UCLA psychologist and addiction researcher Steven Shoptaw called it “an unequal burden on addiction research” compared with other scientific studies.

The California panel has been vetting not only studies that involve federally restricted drugs, but also those assessing any kind of medication to treat addiction, said Dr. Phillip Coffin, a UC San Francisco professor of medicine who has called to eliminate the panel.

“If I’m testing Prozac for depression, or Prozac for any other disease, I can do my research without waiting” for the committee, he said, but “If I’m testing Prozac for addiction, I have to wait.” By maintaining such barriers, Coffin argued, “we are seriously harming any chance California has of responding to the addiction crisis.”

Short of eliminating the panel, some have also argued for amending the law to exempt any researchers who have gotten federal approval to do such research.

Others have argued that the panel has a valuable role, even for studies that have undergone review by the FDA or other entities. An analysis of AB 2841 prepared for the Assembly Committee on Health said state data from the Department of Justice show that the Research Advisory Panel regularly catches issues with drug safety, consent forms missing important information about safety and privacy, and other potential problems.

The panel “has a record of providing an extra level of protection, which is important given the volume of controlled substance research that occurs in California,” the analysis said. In addition, the committee analysis said the panel is “the only one which ensures that studies conducted in California comply with state law.”

Coffin disputed such arguments, saying that in his experience and that of many other researchers, its feedback had not “improved patient safety or remotely justified the extreme delays.”

If it is truly finding problems that have escaped other reviewers, he argued, “then all research — not just addiction treatment and controlled substances — should be forced to go through this panel.”

Science

A mother's loss launches a global effort to fight antibiotic resistance

In November 2017, days after her daughter Mallory Smith died from a drug-resistant infection at the age of 25, Diane Shader Smith typed a password into Mallory’s laptop.

At this point, keeping myself alive is a full-fledged mission, enlisting all of my energy and hours every day. I need to fight the chronic deadly resistant bacteria eating away at my fragile, scarred lungs. Fight the billions of bacteria overtaking my lungs and clear out the mucus so I don’t feel like I’m breathing through a straw with a boulder weighing on my chest.

— Mallory Smith, Oct. 16, 2014

Her daughter gave it to her before undergoing double-lung transplant surgery, with instructions to share any writing that could help others if she didn’t survive.

Had this idea today that I wanted to write down before it leaves my mind or I stop feeling inspired or I forget it or something inside me tells me it’s not possible. I want to start an online media source (podcast? website?) that tells the stories of people who have struggled with something in their life and found hope somewhere.

— Mallory Smith, July 20, 2015

The transplant was successful, but Burkholderia cepacia — an antibiotic-resistant bacterial strain that first colonized her system when she was 12 — took hold. After a lifetime with cystic fibrosis, and 13 years battling an unconquerable infection, Mallory’s body could take no more.

Cepacia has taken over, and it’s time to figure out a transplant option. I realize I want to write my story.

— Mallory Smith, July 29, 2016

In the haze of grief and pain, Shader Smith found herself looking through 2,500 pages of a journal her daughter had kept since high school. It chronicled Mallory’s hopes and triumphs as an ebullient, athletic student at Beverly Hills High School and Stanford University, and her private despair as bacteria ravaged her systems and sapped her considerable strength.

In the years since, the journal has become a source of solace for Shader Smith as she has traveled the globe speaking about the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance. It is also now the inspiration for two new projects she hopes will spark greater understanding of the public health crisis that ended her daughter’s life prematurely and could claim millions more.

“Diary Of A Dying Girl” excerpts Mallory Smith’s own writings, which chronicle her 13-year battle against an antibiotic-resistant lung infection.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

On Tuesday, Random House published “Diary of a Dying Girl,” a selection of Mallory’s journal entries. The same day saw the launch of the Global AMR Diary, a website collecting the worldwide stories of people battling pathogens that can’t be defeated by our current pharmaceutical arsenal.

An estimated 35,000 people die in the U.S. each year from drug-resistant infections, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Worldwide, antimicrobial resistance kills an estimated 1.27 million people directly every year and contributes to the deaths of millions more.

Despite the mounting toll — and the prospect of an eventual surge in superbug fatalities — the development of new antibiotics has stagnated.

Shader Smith is acutely aware of what we stand to lose when medicine can no longer save us.

“I don’t want to live in a post-antibiotic world,” Shader Smith said. “Until people understand what’s at stake, they’re not going to care. My daughter died from this. So I care deeply.”

Over the last 50 years, opportunistic pathogens have evolved defenses faster than humans can develop drugs to combat them.

Misuse of antibiotics has played a large part in this imbalance. Bugs that survive antibiotic exposure pass on their resistant traits, leading to hardier strains.

Crucial as they are, antibiotics don’t have the same financial incentives for developers that other drugs do. They aren’t meant to be taken over the long term, as are medications for chronic conditions such as diabetes or high blood pressure. The most powerful ones have to be used as rarely as possible, to give bacteria fewer opportunities to develop resistances.

“The public does not understand [the] scope of the problem. Antimicrobial resistance truly is one of the leading public health threats of our time,” said Emily Wheeler, director of infectious disease policy at the Biotechnology Innovation Organization. “The pipeline for antibiotics today is already inadequate to address the threats that we know about, without even considering the continuous evolution of these bugs as the years go on.”

Despite the global nature of the threat, Shader Smith said, the response from public health officials is curiously disjointed.

For one, no one can agree on a single name for the problem, she said. Different agencies address the issue with an “alphabet soup” of acronyms: the World Health Organization uses AMR as shorthand for antimicrobial resistance, while the CDC prefers AR. Medical journals, doctors and the media refer alternately to multidrug resistance (MDR), drug-resistant infections (DRI) and superbugs.

“It doesn’t matter what you call it. We just have to all call it the same thing,” said Shader Smith, who works as a publicist and marketing consultant.

Since Mallory’s death, Shader Smith has made it her mission to get the people and organizations working on antimicrobial resistance to talk to one another. For the Global AMR Diary, she enlisted the help of a dozen agencies working on the issue, including the CDC, WHO, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (the European Union’s equivalent of the CDC), the Biotechnology Innovation Organization and others.

Antimicrobial resistance can “feel abstract given the scale of the problem,” said John Alter, head of external affairs of the AMR Action Fund, one of the organizations involved with the project. “To know there are millions of families at this very moment going through struggles similar to what Mallory experienced is simply unacceptable,” he said.

“Not only does this firsthand experience help others who might be going through something similar, but it also reminds those tasked with creating solutions and care who they are working for. They aren’t just test tubes or charts,” said Thomas Heymann, chief executive of Sepsis Alliance, another contributor.

The stories in the online diary are often harrowing. A 25-year-old pharmacist in Athens had to put her cancer treatment on hold when an extremely resistant strain of Klebsiella attacked. A veterinarian in Kenya suffered permanent disability after contracting resistant bacteria after hip surgery. Around the world, routine outpatient procedures and illnesses have rapidly become life-threatening when opportunistic bugs take hold.

Mallory was 12 when her doctor called to confirm that her cultures were positive for an extremely resistant strain of cepacia, a form of bacteria found widely in soil and water. The pathogen can be deadly to people with underlying conditions such as cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that impairs the cells’ ability to effectively flush mucus from the lungs and other body systems.

Life expectancies for people with cystic fibrosis have grown since Mallory’s diagnosis in 1995, with many people of them living into their 40s and beyond. The cepacia curtailed that possibility for her.

“This is all we’re ever going to have,” Mallory wrote in June 2011, at the end of her freshman year at Stanford, “so if you’re not actively pursuing happiness then you’re insane. And I don’t think I would have this perspective if I didn’t have resistant bacteria that will likely kill me.”

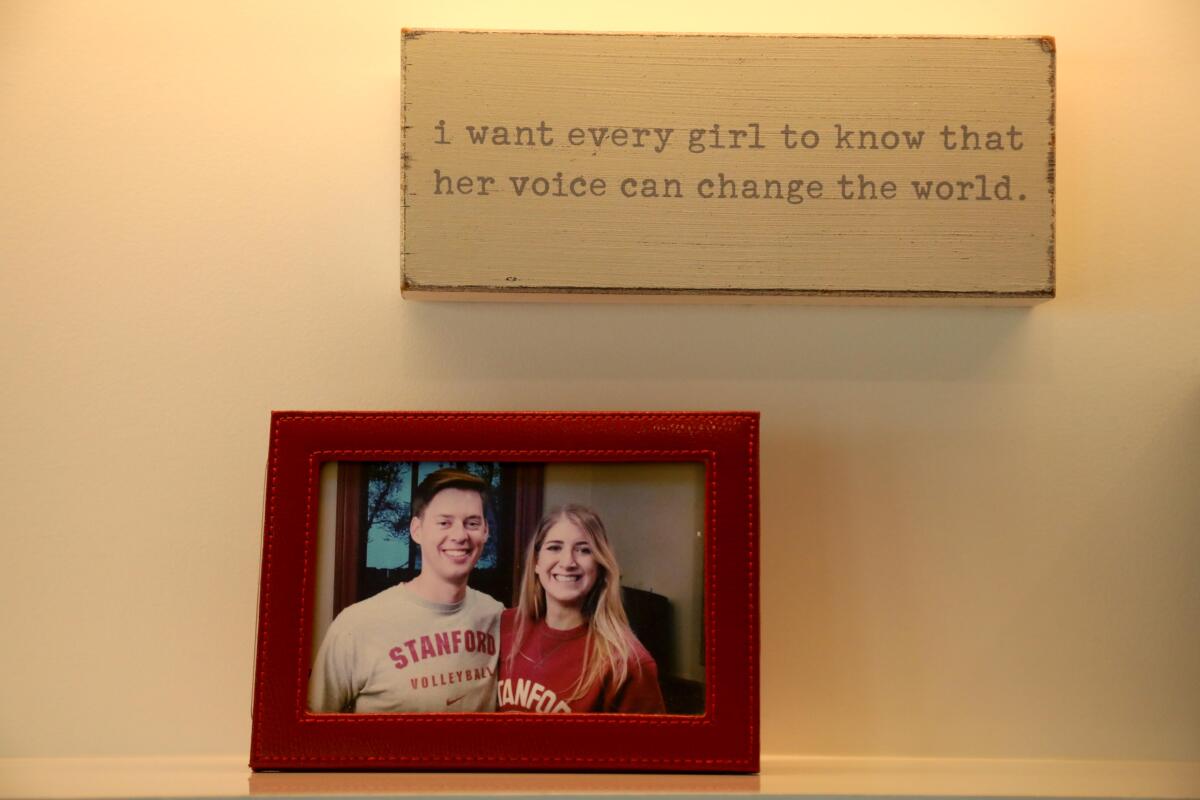

A shrine to Mallory Smith. She fought a drug-resistant bacteria from age 12 to 25, all through high school, then at Stanford. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Mallory’s intuition that her journal could be valuable to others was prescient. “People can easily understand and relate to actual experiences,” said Michael Craig, director of the CDC’s Antimicrobial Resistance Coordination and Strategy Unit. “The Global AMR Diary takes this approach and expands on it with a global lens — increasing the potential to get these critical messages to more people around the world.”

An earlier version of Mallory’s diaries was published in 2019 as “Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life.” The new book includes entries that Shader Smith said she wasn’t ready to grapple with in the immediate aftermath of Mallory’s passing: ones addressing depression and private despair, concerns about relationships and body image issues complicated by chronic illness.

It also includes a coda about phage therapy, a promising advance against AMR.

As cepacia overwhelmed Mallory’s system in the weeks after her transplant, her family secured an experimental dose of phage therapy. Widely used to treat infection before the advent of antibiotics, phages are viruses that destroy specific bacteria. The treatment arrived too late to save Mallory’s life, Shader Smith writes in a last chapter of the book, but her autopsy revealed that the phages had started to work as intended.

The systems that bring new drugs to patients move slowly, Shader Smith said, and “Mallory might have been saved if they had moved faster.” Her mission now is to make sure that they do.

“Mallory died six years ago. Six years is a long time, day in and day out,” she said. “And I’ve never taken my foot off the pedal.”

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Republicans brace for spring legislative sprint with one less GOP vote

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAt least four dead in US after dozens of tornadoes rip through Oklahoma

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoStefanik hits special counsel Jack Smith with ethics complaint, accuses him of election meddling

-

Politics1 week ago

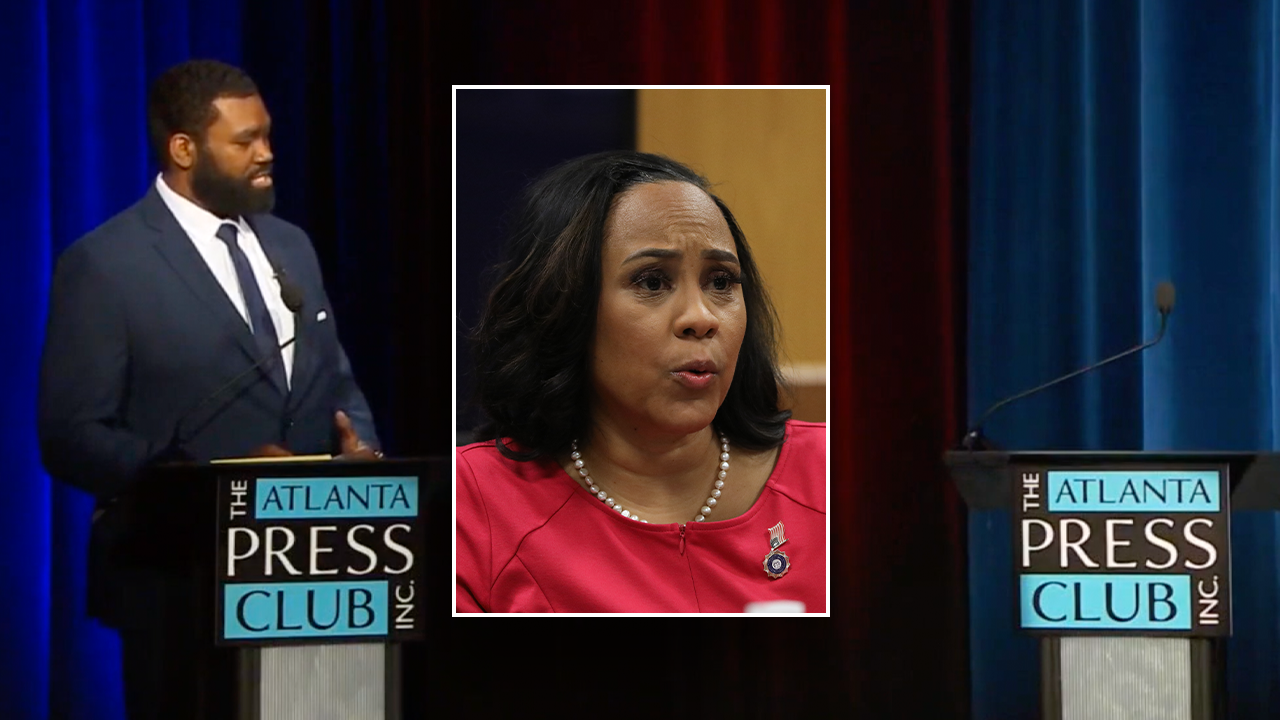

Politics1 week agoAnti-Trump DA's no-show at debate leaves challenger facing off against empty podium

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Police Arrest Columbia Protesters Occupying Hamilton Hall

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAs student protesters get arrested, they risk being banned from campus too

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoNine on trial in Germany over alleged far-right coup plot

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoThe White House has a new curator. Donna Hayashi Smith is the first Asian American to hold the post