Science

An Ancient Whale Named for King Tut, but Moby-Dinky in Size

In 1842, a vast, nearly intact skeleton was unearthed on a plantation in Alabama; it was soon identified as a member of Basilosaurus, a recently named genus of prehistoric sea serpent. But when some of its enormous bones were shipped to England, Richard Owen, an anatomist, noted that its molars had two roots, not one, a dental morphology unknown in any reptile. He determined that the fossil was actually a marine mammal: a primitive whale. Herman Melville name-drops the behemoth — Mr. Owen called it Zeuglodon — in Chapter 104 of “Moby-Dick,” and Mr. Owen, in a paper that he read to the London Geological Society, pronounced it “one of the most extraordinary creatures which the mutations of the globe have blotted out of existence.”

In August, a team of paleontologists announced the discovery of another extraordinary creature that was blotted out of existence. Eleven years ago, while working in the Fayum Depression of the Western Desert in Egypt, the team excavated the fossil of what they initially thought was a small amphibian. But closer inspection revealed that the bones belonged to a previously unknown species of miniature whale that existed during the late middle Eocene, in a period called the Bartonian Age, which lasted from about 48 million to 38 million years ago. The species, described in a paper in the journal Communications Biology, inhabited the Tethys Sea, the tropical precursor of the Mediterranean, which covered about a third of what is now northern Africa.

Ishmael, the protagonist of “Moby-Dick,” asserts somewhat disingenuously that a whale is a “spouting fish with a horizontal tail.” The newly documented specimen looked less like a fish than a bottlenose dolphin, with a less-bulbous forehead and a more elongated body and tail. Based on a skull, jaw, teeth and vertebrae fragments embedded in compacted limestone, researchers inferred that the wee whale, which dates back some 41 million years, was about eight feet long and weighed roughly 400 pounds, making it the tiniest known member of the basilosaurid family.

All whales are descended from terrestrial animals that ventured into the sea. Some early whales evolved into forms that ventured back onto land; basilosaurids are thought to be the first widespread group to have stuck with the sea life. They were also the last to have hind limbs that were still recognizable as legs, which were probably used less for locomotion than as reproductive guides to help orient the whales during sex.

Melville dismissed whale taxonomy as “mere sounds, full of Leviathanism, but signifying nothing.” He likely would have had little use for Tutcetus rayanensis, the official name of the small-scale whale ancestor. Tutcetus combines Tut — recalling the pharaoh Tutankhamen — and cetus, Greek for whale. The designation also follows the centenary of the discovery of King Tut’s tomb, and coincides with the impending opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, Egypt. The “rayan” part of the name derives from the Wadi El-Rayan Protected Area, which sits about 25 miles northeast of a site so rich in fossil whales that it has been called Wadi Al-Hitan, or Valley of the Whales.

Like Tut, who died in the Valley of the Kings at age 18, the whale is believed to have been a juvenile nearing adulthood. The research team used CT scanning to analyze Tutcetus’s teeth and bones, reconstructing its growth patterns. The bones of the skull had fused, as had parts of the first vertebrae, and while some of the teeth had emerged, some were still in transition. The rapid dental development and small bone size of Tutcetus suggest a short, fast life compared with larger and later basilosaurids, said Hesham Sallam, a paleontologist at the American University of Cairo and leader of the project.

The whale may have been able to feed itself and move independently almost from birth, researchers said. The soft enamel and configuration of its teeth suggest that it was a meat-eater, with a diet of aquatic animals.

The discovery challenges some conventional assumptions about the life history of primitive whales. “The geological age of Tutcetus is a bit older than other closely related fossil whales, which hints that some evolutionary changes in whale anatomy happened a bit earlier than we suspected,” said Nicholas Pyenson, curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, who was not involved in the work. “The fossil pushes back the timing of how the earliest whales changed from foot- to tail-propelled movement in the water.”

Whales have an unexpected past. Genetically they are closely related to hoofed mammals, called ungulates, and within that group they are most similar to the artiodactyls, such as camels, pigs, giraffes and hippos, all of which have an even number of toes. One of the best-known early forebears of whales was a 50-million-year-old quadruped called Pakicetus that waded in the estuaries of southern Asia, ate meat and, by some accounts, might have resembled a large house cat with hoof-like claws.

Scientists were able to link Pakicetus to the evolutionary lineage of whales because it had an ear bone with a feature unique to those modern-day giants of the deep. “Importantly, its ankle bones look like those of artiodactyls and helped to support the link of whales to artiodactyls that had previously been suggested by DNA,” said Erik Seiffert, an anatomist at the University of Southern California who collaborated on the paper.

The artiodactyls begot the semiaquatic ambulocetus, a so-called walking whale that looked like a crocodile, swam like an otter and waddled on land like a sea lion. “Ambulocetus actually still had fairly well-developed hind limbs, so it wouldn’t have had a hard time getting around on land,” Dr. Seiffert said. Ambulocetus, in turn, begot protocetid, a more streamlined halfway creature that fed in the sea, but may have returned to land to rest. Over evolutionary time, its hind limbs became smaller, and it maneuvered entirely with its tail.

Eventually, these proto-cetaceans gave rise to archaeocet, a fully aquatic basilosaurid. Aided by flippers and paddle-like tails, basilosaurids dispersed through the oceans worldwide. The one that turned up on that Alabama plantation in 1842 may even have crossed the Atlantic.

Mohammed Antar, a paleontologist at Mansoura University who dug up the Tutcetus fossil and was first author of the new paper, said climate and location may have made the Fayum Depression inviting to basilosaurids. “Modern whales migrate to warmer, shallow waters for breeding and reproduction, mirroring the conditions found in Egypt 41 million years ago,” he said.

The setting seems to have provided relatively safe harbor for female whales to give birth in shallow waters. “As far as we can tell from the abundant fossils of tree-living primates found there, the area lining the northern edge of what is now the Sahara was effectively a tropical forest during the middle Eocene,” Dr. Seiffert said. The protected coasts of northern Africa, he added, “might have allowed whale calves time to mature and reach a level of navigational and feeding proficiency before heading out into open water, then very deep water.”

In August, shortly before the diminutive Tutcetus was unveiled in Egypt, paleontologists working in Peru reported the discovery of an extinct whale that may have been the heaviest animal ever. Perucetus colossus swam the oceans 38 million years ago and is estimated to have weighed as much as 200 tons, a figure comparable to the blue whale, the current record-holder.

Perucetus and Tutcetus were alive just a few million years before primitive whales began their evolutionary split into the two cetacean suborders of today: the toothed whales, dolphins and porpoises known as odontoceti, and the baleen-bearing mysticeti, including blue whales and humpbacks.

“The mysticetes tend to be much larger than the odontocetes,” said Jonathan Geisler, an anatomist at the New York Institute of Technology. “And this difference is related to their different feeding strategies.” Toothed whales hunt individual prey such as fish and squid, while baleen whales filter-feed to gather krill, copepods and tiny schooling fish.

“Understanding the size of the ancestor of all modern whales helps us understand how these feeding behaviors and distinct body size differences evolved,” Dr. Geisler said. “Tutcetus is one data point in the effort, but it supports the hypothesis that the common ancestor of all living cetaceans was fairly small.”

Dr. Sallam said that similar to the way Melville, reflecting on the Basilosaurus skeleton found in 1842, imagines a time when “the whole world was the whale’s,” the discovery underscores the transient nature of existence and provides a tangible connection to a prehistoric past. “The significance of the find, like the fossils described in ‘Moby Dick,’ extends beyond the realm of paleontology,” he said. “It highlights the enduring fascination with Earth’s ancient history.”

Science

Trump Administration Delays Plan to Limit Pricey Bandages

The Trump administration announced Friday it would delay the implementation of a Biden-era rule meant to restrict coverage of unproven and costly bandages known as skin substitutes.

The policy will be delayed until 2026, allowing companies to continue setting high prices for new products, taking advantage of a loophole in Medicare rules. The companies sell those bandages at a discount to doctors, who then charge Medicare the full sticker price and pocket the difference, The New York Times reported on Thursday.

Medicare spending on the coverings soared to over $10 billion in 2024, up from $1.6 billion in 2022, according to an analysis done by Early Read, an actuarial firm that evaluates costs for large health companies. Some experts said the bandage spending was one of the largest examples of waste in the history of Medicare, the insurance program for seniors.

A super PAC for President Trump’s election campaign had received a $2 million donation from Extremity Care, a leading seller of skin substitutes. Mr. Trump has twice criticized the policy on social media, saying it would hurt patients who use the products on diabetic sores.

“‘Crooked Joe’ rammed through a policy that would create more suffering and death for diabetic patients on Medicare,” Mr. Trump posted on Truth Social in March.

Extremity Care had also criticized the plan, arguing that it would disrupt supply chains, eliminate innovation and increase costs for both doctors and patients. The company, which has said that it adheres to high ethical standards, did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the policy’s new delay.

More than 120 skin substitutes are on the market. They cost $5,089 per square inch on average, The Times found, with the most expensive exceeding $23,000.

The Biden-era rule would have restricted Medicare coverage to a small subset of products that have been shown to be effective in randomized clinical trials. The new policy applies to patients using the bandages on foot and leg sores, known as ulcers, which can be caused by diabetes or poor circulation.

Medicare said in a statement Friday that as part of the transition to a new administration, it would be reviewing the policy. During that time, it said it “believes it is important to maintain patient access to skin substitute products with high quality evidence of effectiveness.”

The MASS Coalition, a group that supports the skin substitute industry, said it was “pleased” with the delay, which it said would give the Trump administration time to evaluate the policy change. A spokeswoman, Preeya Noronha Pinto, said the group is looking forward to working with Medicare “on a coverage policy and payment reform that ensures access to skin substitutes.”

Science

Funding for National Climate Assessment Is Cut

The Trump administration has cut funding and staffing at the program that oversees the federal government’s premier report on how global warming is affecting the country, raising concerns among scientists that the assessment is now in jeopardy.

Congress requires the federal government to produce the report, formally known as the National Climate Assessment, every four years. It analyzes the effects of rising temperatures on human health, agriculture, energy production, water resources, transportation and other aspects of the U.S. economy. The last assessment came out in 2023 and is used by state and city governments, as well as private companies, to prepare for global warming.

The climate assessment is overseen by the Global Change Research Program, a federal group established by Congress in 1990 that is supported by NASA and coordinates efforts among 14 federal agencies, the Smithsonian Institution and hundreds of outside scientists to produce the report.

On Tuesday, NASA issued stop-work orders on two separate contracts with ICF International, a consulting firm that had been supplying most of the technical support and staffing for the Global Change Research Program. ICF had originally signed a five-year contract in 2021 worth more than $33 million and provided around two dozen staff members who worked on the program with federal employees detailed from other agencies.

Without ICF’s support, scientists said, it is unclear how the assessment can move forward.

“It’s hard to see how they’re going to put out a National Climate Assessment now,” said Donald Wuebbles, a professor in the department of atmospheric sciences at the University of Illinois who has been involved in past climate assessments. But, he added, “it is still mandated by Congress.”

In a statement, a NASA spokeswoman said that the agency was “streamlining its contract providing technical, analytical and programmatic support for the U.S. Global Change Research Program” to align with President Trump’s executive orders. She added that NASA planned to work with the White House to figure out “how best to support the congressionally mandated program while also increasing efficiencies across the 14 agencies and advisory committee supporting this effort.”

The contract cancellation came a day after The Daily Wire, a conservative news website, reported on ICF’s central role in helping to produce the National Climate Assessment in an article titled “Meet the Government Consultants Raking in Millions to Spread Climate Doom.”

ICF did not respond to a request for comment. The cancellation was first reported by Politico.

Many climate scientists were already expecting that the next National Climate Assessment, due in 2027 or 2028, was very likely in trouble.

Mr. Trump has long dismissed climate change as a hoax. And Russell Vought, the current director of the Office of Management and Budget, wrote before the election that the next president should “reshape” the Global Change Research Program, since its scientific reports on climate change were often used as the basis for environmental lawsuits that constrained federal government actions.

During Mr. Trump’s first term, his administration tried, but failed, to derail the National Climate Assessment. When the 2018 report came out, concluding that global warming posed an imminent and dire threat, the administration made it public the day after Thanksgiving in an apparent attempt to minimize attention.

“We fully anticipated this,” said Jesse Keenan, an associate professor at the Tulane School of Architecture who was an author of a chapter of the National Climate Assessment on how climate change affects human-made structures. “Things were already in a very dubious state,” he said.

The climate assessment is typically compiled by scientists around the country who volunteer to write the report. It then goes through several rounds of review by 14 federal agencies, as well as public comments. The government does not pay the scientists themselves, but it does pay for the coordination work.

In February, scientists had submitted a detailed outline of the next assessment to the White House for an initial review. But that review has been on hold, and the agency comment period has been postponed.

Ladd Keith, an associate professor at the University of Arizona specializing in extreme heat governance and urban planning, had been helping to write the chapter on the U.S. Southwest. He said that while outside scientists were able to conduct research on their own, much of the value of the report came from the federal government’s involvement.

“The strength of the National Climate Assessment is that it goes through this detailed review by all the federal agencies and the public,” Dr. Keith said. “That’s what makes it different from just a bunch of academics getting together and doing a report. There are already lots of those.”

Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University, said the assessment was essential for understanding how climate change would affect daily life in the United States.

“It takes that global issue and brings it closer to us,” Dr. Hayhoe said. “If I care about food or water or transportation or insurance or my health, this is what climate change means to me if I live in the Southwest or the Great Plains. That’s the value.”

Austyn Gaffney and Lisa Friedman contributed reporting.

Science

Hantavirus caused three recent deaths in California. Here's what to know about the virus

Three people in Mammoth Lakes died recently after contracting hantavirus, the same infection that killed Gene Hackman’s wife Betsy Arakawa earlier this year. The cases have heightened concerns among public health officials about the spread of the rare, but deadly disease that attacks the lungs.

At a news conference last month, Dr. Heather Jarrell, chief medical examiner at the New Mexico medical investigator’s office, said that the mortality rate is between 38% and 50% among those infected in the American Southwest. It wasn’t on many people’s radar until New Mexico’s chief medical examiner confirmed Arakawa, 65, died from hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in March.

The virus can spread through the urine, feces or saliva of wild rodents, including deer mice, which are common in many parts of California, according to the California Department of Public Health.

All three individuals who contracted and died from the virus in Mammoth Lakes experienced symptoms beginning in February. Of the three, only one had numerous mice in their home, according to health officials — however, there was evidence of mice in the places where all three had worked.

That “is not unusual for indoor spaces this time of year in Mammoth Lakes,” said Dr. Tom Boo, a public health officer for Mono County, home to Mammoth Lakes.

“We believe that deer mouse numbers are high this year in Mammoth, and probably elsewhere in the Eastern Sierra,” he said. “An increase in indoor mice elevates the risk of hantavirus exposure.”

Mono County has reported 27 cases of hantavirus since 1993, the most of any county in California.

Has hantavirus been detected in Los Angeles County before?

Hantavirus is rare in Los Angeles County, and most cases have been linked to out-of-county exposure. Los Angeles County’s last reported hantavirus-related death was in 2006.

Even though rodents are more likely to be found in rural and semi-urban areas, any area or structure that the animals take up as a home can be a concern when it comes to infectious disease, whether it’s in a city or out in the country. Infrequently used buildings such as sheds, cabins, storage facilities, campgrounds and construction sites are particularly at risk for rodent infestation.

How can you protect yourself against hantavirus?

Hantavirus cases can occur year-round, but the peak seasons for reported cases in the United States are spring and early summer — which coincide with the reproductive seasons for deer mice.

To limit the risk of infection, avoid rodents, their droppings and nesting materials.

In addition, do what you can to keep wild rodents out of your home, workplace, cabin, shed, car, camper, or other closed space.

To do so, Los Angeles County public health officials suggest:

- Sealing up holes (the width of a pencil or larger) and other openings where rodents like mice can get in.

- Place snap traps to catch any rodents (The CDC cautions against using glue traps or live traps because they can scare the rodents, causing them to urinate, which increases your chance of exposure to any virus they may be carrying.)

- Store all food items in rodent-proof containers .

If you discover evidence of mice in your home or workplace, set up snap traps and clean up their waste.

If that occurs, local and state officials offer the following guidance on how to clean up while protecting yourself against exposure:

Before you clean:

- Air out the space you will be cleaning for 30 minutes.

- Get rubber or plastic gloves, an N-95 mask and a disinfectant or a mixture of bleach and water.

While cleaning (with gloves on):

- Spray the contaminated areas with your disinfectant and let it soak for at least 5 minutes.

- Do not sweep or vacuum the area — that could stir up droppings or other infectious materials into the air.

- Use paper towels, a sponge, or a mop to clean. Put all cleaning materials into a bag and toss it in your trash bin.

What to expect if you do contract the hantavirus

Symptoms are similar to other respiratory infections, which include fever, headache, muscle aches and difficulty breathing. Some people also experience nausea, stomach pain, vomiting and diarrhea.

The symptoms usually develop weeks after breathing in air contaminated by infected deer mice.

Complications of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome can lead to damaged lung tissues and fluid buildup in the lungs, according to the Mayo Clinic. It can also affect heart function; severe cases may result in failure of the heart to deliver oxygen to the body. The signs to look out for include cough, difficulty breathing, low blood pressure and irregular heart rate.

What can you do to treat hantavirus pulmonary syndrome?

There isn’t specific treatment or a cure for the disease, according to the American Lung Assn. However, early medical care can increase the chances of survival.

If the virus is detected early and the infected person receives medical attention in an intensive care unit, the ALA said, there is a chance the person will improve.

The ICU treatment may include intubation and oxygen therapy, fluid replacement and use of medications to lower blood pressure.

If your symptoms become severe call your healthcare provider.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court Rules Against Makers of Flavored Vapes Popular With Teens

-

News1 week ago

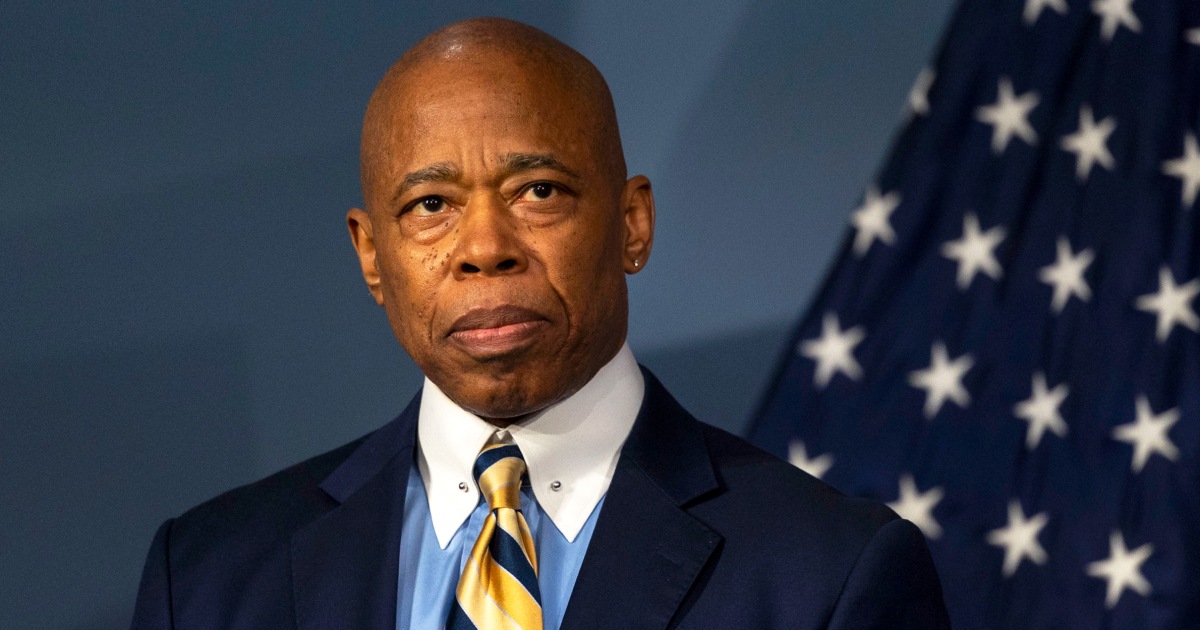

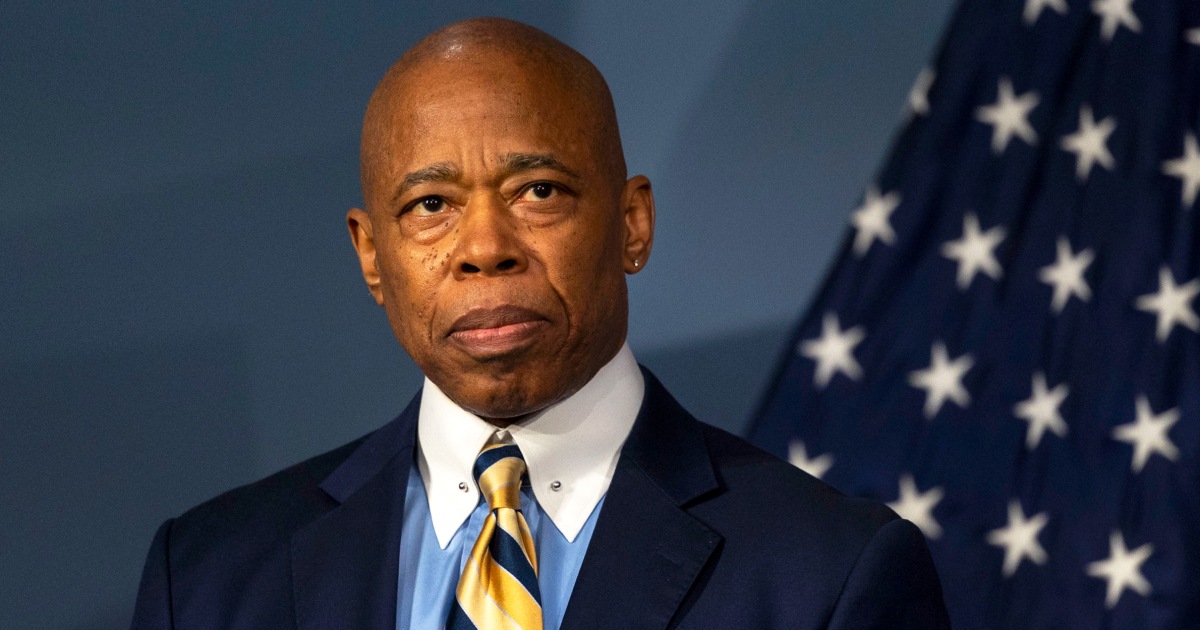

News1 week agoNYC Mayor Eric Adams' corruption case is dismissed

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoHere’s how you can preorder the Nintendo Switch 2 (or try to)

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump to Pick Ohio Solicitor General, T. Elliot Gaiser, for Justice Dept. Legal Post

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFBI flooded with record number of new agent applications in Kash Patel's first month leading bureau

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘A historic moment’: Donald Trump unveils sweeping ‘reciprocal’ tariffs

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoDeion Sanders defied doubters and returns to Colorado with a $10M per year deal. What’s next?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCommission denies singling out NGOs in green funding row