Nearly a year after catastrophic flooding struck Vermont, the city of Barre confronts the overwhelming task of steeling itself for the next climate disaster.

Vermont

Q&A: New Legislation in Vermont Will Make Fossil Fuel Companies Liable for Climate Impacts in the State. Here’s What That Could Look Like – Inside Climate News

From our collaborating partner “Living on Earth,” public radio’s environmental news magazine, an interview by host Paloma Beltran with Pat Parenteau, an emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law and Graduate School.

Vermont’s House and Senate have approved a bill that would make fossil fuel companies financially liable for their carbon pollution and its role in the climate crisis. Lawmakers pointed to consequences of these carbon emissions, like the flood in July 2023 that put parts of the state capital underwater for weeks and caused over a billion dollars in damage.

The bipartisan bill is known as the Climate Superfund Act because it demands that fossil fuel companies cover at least part of the growing costs of climate change. Similar bills are being considered in New York, Massachusetts and Maryland, but Vermont is the first state to pass this kind of legislation. The bill passed with a supermajority, enough to override a potential veto. It is now headed to Governor Phil Scott’s desk.

Living on Earth spoke with Pat Parenteau, former EPA regional counsel and emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School, to unpack the details. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

PALOMA BELTRAN: What is the Climate Superfund law in Vermont? What does it say?

PAT PARENTEAU: It’s basically asking fossil fuel companies to contribute to the costs for adaptation to the unavoidable impacts of climate change, including protection of homes and businesses threatened by flooding, building resilience in floodplains by moving structures out of harm’s way, investing in wetland protection and natural systems that absorb carbon emissions and provide for more resilience to extreme weather events. It’s a new approach, and Vermont is the first state in the country to try it.

BELTRAN: How is this law different from the climate deception lawsuits like the one we’ve seen filed in the state of Hawaii?

PARENTEAU: This law doesn’t depend on proof of deception, or false advertising, or the campaign to sow doubt about climate change that the companies are accused of in over 30 lawsuits across the country. The companies are liable by virtue of what they do. It’s not that they’ve committed anything wrong, necessarily—”polluter pays” is the concept here.

The fact that your product creates carbon pollution, which is driving climate change, that’s enough to make you liable, in the same way, or at least a similar way, to how the Superfund law at the federal level makes you responsible for contamination of soil and groundwater as a result of your activities at a site. You may have generated chemical waste that wound up at the site, you may own the site, you may operate a landfill or other facility that’s become contaminated.

The Superfund law says, by virtue of the fact that you own or operate or generate waste, you’re liable. In the same way, this law is saying the fact that you extract and burn fossil fuels is enough to make you liable for the damage that results from that.

BELTRAN: How might the state of Vermont go about calculating which companies owe what? What are the possible methods they could use here?

PARENTEAU: That is the big question. The formula that the law is using—and the state treasurer will have to flesh this out—is to say, what is the individual company’s share in the global emissions? The law also directs the state to use the Environmental Protection Agency’s greenhouse gas inventory as a starting point.

The greenhouse gas inventory has something called emission factors. For example, for the big oil companies, they can disaggregate among the different companies, what their emissions factor is for the amount of oil and gas they’re producing. So it’s going to be a proportionate share, based on what the individual company’s emissions are. That’s going to be the basic formula.

BELTRAN: It’s a big job, to calculate all of that.

PARENTEAU: Yes. And then from there, you have to say, well, what percentage of harm is the emissions doing on top of the natural cycle of flooding, for example, just sticking with the flooding example.

There are other impacts of climate change in Vermont. There’s impacts on the ski industry, there’s impacts on the sugar-making industry—our famous syrup.

But just in terms of flooding, what you have to calculate is, by how much has climate change increased the damage from flooding that normally would occur in Vermont? The flooding of Montpelier was definitely much greater than any prior flood we’d ever had. But you have to calculate how much worse was it as a result of the emissions from these companies? That’s another tricky calculation.

BELTRAN: How are these oil companies expected to respond?

PARENTEAU: We know that the oil companies are not going to start sending checks to Vermont. The oil companies have been fighting tooth and nail against all of the other lawsuits that have been brought against them. And we can expect the same thing here.

The companies have a choice to make. They can either file what’s called a preemptive strike and challenge the law on constitutional grounds. For example, they may argue that this is a violation of due process to make them liable, when they haven’t, quote, done anything wrong. They’re producing a valuable product that people are still buying to put into their automobiles, to heat their homes and so forth. They’re going to say, “You’re making us liable for engaging in economic activity that’s lawful? How can you do that? That’s not constitutional.”

Similar arguments were made against Superfund, the federal law. And it took several years for those arguments to finally be resolved in the court. Ultimately, it went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In the Superfund case, there is precedent for establishing liability for the damage that legal activity is causing.

But whether that precedent under Superfund extends to the climate liability context, that’s going to be a major issue; that’s a novel issue.

One option for the companies might be to challenge the law on its face. The other option would be to wait until Vermont actually sends them a bill, a demand for payment, and then not pay, in which case Vermont would have to initiate a lawsuit to collect the money that they’ve demanded.

Either way, this issue is sure to end up in court. And it will take the usual long time for it to finally get settled.

BELTRAN: What are some of the concerns raised by opponents of the law other than these oil companies?

PARENTEAU: The opposition to passage of the law came from those who are concerned that Vermont is too small a state to take on these major multinational corporations, that, as we’ve discussed, isn’t going to just happen without litigation.

The litigation that’s underway in other states has shown just how expensive it is to sue these companies. These companies really fight hard, which means the cost of litigation can be measured easily in the millions. Some of the people who questioned this law were saying Vermont is too small to take this on; let some of the bigger states do it—let New York do it. And we can follow in their wake, but don’t take the first hit from these companies.

The costs of litigating against the oil companies, not only are they not small, but there’s not enough money in Vermont to do everything that needs to be done. The big question is, what’s the best use of the money we have? Is it to fight the oil companies to try to get them to pay? There’s a good case to be made that that’s appropriate. But the contrary case is that’s going to take a really long time, with uncertain results. And so maybe the better approach is to spend the money you do have with direct assistance to the communities most affected by climate change, and let some of these other states go first.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

BELTRAN: What are the broader consequences of this law in Vermont? How will this impact the rest of the country, and potentially the rest of the globe?

PARENTEAU: I do think we’re going to see other states adopting similar legislation. And I do think the underlying theory of these laws, that the oil companies should pay their fair share to address the damage that’s being done, even if their product was a valuable product for many years, the truth is, we now know, it’s causing damage.

Under the “polluter pay” rule, which is one of the pillars of environmental law and policy, what Vermont is doing and what I think many other states are going to be doing is looking to the oil companies, which are some of the wealthiest companies on earth, to pay their fair share for the damage that’s being done.

In that sense, I think this movement that Vermont has begun has merit. And I think it will put greater pressure on the oil companies to either agree under some circumstances to contribute to the costs of dealing with climate or be forced to do so by a court at some point. There’s a legal and a moral case to be made for holding companies responsible. And we’ll now see how fast that can happen.

Vermont

How ruinous floods put Vermont at the forefront of the climate battle

Across the country, state and local leaders are scrambling to find the money they need to protect their communities from worsening disasters fueled by climate change. For Barre, needed flood mitigation projects will cost the city an estimated $30 million over the next five years, Lauzon said.

Yet Vermont has a new answer to this problem.

Earlier this month, it became the nation’s first state to require fossil fuel companies and other big emitters to pay for the climate-related damage their pollution has already caused statewide. While conservative legal experts are skeptical the law will survive challenges, some Vermonters said they are both grateful and a little nervous that one of the nation’s least populous states has picked a fight with one of America’s most powerful industries.

“I’m proud to have this state stand up and say, ‘Look, you need to be held accountable, and you need to help us with the damage we incurred,’” Lauzon said. “But I’m also scared to death. I feel like we’re a pee wee football team going up against the 2020 New England Patriots.”

The Vermont law comes as oil and gas companies face dozens of climate lawsuits, both in the United States and abroad. While none of the state and local lawsuits have gone to trial yet — including Vermont’s own challenge, filed in 2021 — they pose a growing threat and add to the companies’ potential liabilities. If Vermont’s novel approach endures, it could reverberate across the industry.

Republicans are pushing back, arguing that individual states cannot apply their own laws to a global pollutant. Last month, Republican attorneys general in 19 states asked the Supreme Court to block the climate change lawsuits brought by California, Connecticut, Minnesota, New Jersey and Rhode Island against fossil fuel companies.

Vermont’s law authorizes the state to charge major polluters a fee for the share of greenhouse gas emissions they produced between 1995 and 2024. It is modeled on the 1980 federal Superfund law, which forces polluting companies to clean up toxic waste sites.

The law doesn’t spell out how much money should be paid; instead, it tasks the state treasurer with assessing the damage Vermont has suffered from climate change and what it will cost to prepare for future impacts. The final tally is expected to be comprehensive, factoring in an array of possible costs from rebuilding and raising bridges and roads to lower worker productivity from rising heat.

Bills similar to Vermont’s have been introduced in several states, including California, Maryland and Massachusetts. Last week, New York lawmakers passed a climate superfund law that would require polluters to pay $3 billion a year for 25 years. It is now awaiting Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul’s signature.

The timing of the Vermont law was no accident, said Ben Edgerly Walsh, the climate and energy program director of the Vermont Public Interest Research Group. Memories of last July’s flooding — which inundated the state capitol of Montpelier, damaged thousands of homes and trapped people in small mountain towns — are still fresh.

Over the last year, Vermonters have also endured a freak late-spring frost that damaged crops, hazy skies from smoke blown south from hundreds of wildfires in Canada, and more flooding in mid-December. All these events primed state lawmakers to tackle climate change at the beginning of 2024.

“When we brought this idea to legislators, they came to it with a very open mind in a way that may have taken more time, more convincing, in another year,” Edgerly Walsh said. “But this was a moment we just knew we needed to act.”

As disaster recovery costs mount, it has not been lost on state leaders that oil companies are enjoying massive profits. In 2023, the warmest year on record, the two largest U.S. energy companies, ExxonMobil and Chevron, together made more than $57 billion.

It might seem unlikely for a state like Vermont, with a population just under 650,000, to stand up to the fossil fuel industry. The state’s Republican governor, Phil Scott, expressed skepticism in a letter to the secretary of the Vermont Senate, writing, “Taking on ‘Big Oil’ should not be taken lightly. And with just $600,000 appropriated by the Legislature to complete an analysis that will need to withstand intense legal scrutiny from a well-funded defense, we are not positioning ourselves for success.”

Yet Vermont’s small budget — it has the lowest GDP in the country — means that it feels the rising risks from heavy rains more acutely than wealthier states. A report by Rebuild by Design, a nonprofit that helps communities recover from disasters, found that Vermont ranked fifth nationally in per capita disaster relief costs from 2011-2021, with $593 spent per resident.

The costs are only expected to climb. A 2022 study from University of Vermont researchers predicted that the cost of property damage from flooding alone may top $5.2 billion over the next 100 years.

Ultimately, the governor allowed the law to go into effect without his signature, saying he understood “the desire to seek funding to mitigate the effects of climate change that has hurt our state in so many ways.”

Legal challenges will inevitably follow — the only question is when.

The oil and gas industry’s top lobbying group, the American Petroleum Institute, has said that states don’t have the power to regulate carbon pollution and can’t retroactively charge companies for emissions allowed under the law. It has also emphasized individuals’ responsibility for climate change, noting that Vermont residents use fossil fuels to heat their homes and power their cars. Scott Lauermann, a spokesman for the group, said API is “considering all our options to reverse this punitive new fee.”

“I think the courts are going to have problems with the idea that Vermont can penalize the companies for past actions that were completely legal and the state itself relies on,” said Jeff Holmstead, an energy lawyer who served in the Environmental Protection Agency under George W. Bush. “I’m skeptical this will actually pass muster.”

Supporters and environmentalists involved in drafting the law said they believed they had created a legally defensible way to recover damages from polluters by modeling it after the Superfund law, which has been repeatedly upheld in court. Several legal experts said the state had also taken a more conservative approach than others by requiring a study before assessing companies’ liability, ensuring the fines levied against them are proportional to the amount of damage caused by their products.

Cara Horowitz, executive director of the UCLA School of Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, said that, inevitably, fossil fuel companies will challenge any bills Vermont submits for damages. But that is years off, she said, and the industry is likely to move sooner than that.

The lawsuits “will start soon and last a long time,” Horowitz said. “It would surprise me if they don’t preemptively try to undermine the entire exercise by declaring the whole thing unlawful.”

In Barre, Lauzon said he isn’t confident litigation over the law will be resolved in his lifetime. But even if the fossil fuel companies are never made to pay, he said, the law’s passage was the right thing to do.

“I can’t look at the north end, I can’t look at the city of Barre and say no one needs to be held accountable,” he said.

Vermont

Vt. author releases book on dealing with betrayal

BURLINGTON, Vt. (WCAX) – A Vermont author has released a new book to help people trying to recover from betrayal.

Bruce Chalmer is a psychologist and couples counselor. He says he wrote “Betrayal and Forgiveness: How to Navigate the Turmoil and Learn to Trust Again” because he found many of his clients were dealing with some kind of betrayal by someone they trusted.

Chalmer says the couples he has worked with who are able to find the meaning in it are the ones who can heal.

“When I say heal, they don’t always stay together. You can heal and not stay together, heal and stay together. But especially the ones that heal and are able to stay together. I find it very inspiring, and I wanted to write a book that talked about what it was about those couples that made it possible for them to heal in that way.”

Watch the video to see our Cat Viglienzoni’s full conversation with Chalmer.

Click here for more on “Betrayal and Forgiveness: How to Navigate the Turmoil and Learn to Trust Again” and where to buy it.

Copyright 2024 WCAX. All rights reserved.

Vermont

Two sought in Starksboro kidnapping, assault – Newport Dispatch

NEWPORT — On June 12, Vermont State Police responded to a reported kidnapping and assault stemming from an incident that took place on June 8 on Vermont Route 116 in Starksboro.

Authorities have identified the suspects as Anthony Seagroves, 32, from Hinesburg, and Katelynn Cannon, 28, from Essex.

The investigation alleges that Seagroves, armed with a baseball bat, coerced an adult household member into a vehicle and inflicted bodily harm while restraining the individual.

Cannon is accused of aiding Seagroves and assaulting the victim, attempting to cause serious injury.

Efforts to apprehend Seagroves on June 13 led to a pursuit when he fled in a gray Honda CR-V, with Vermont plates CRW914, believed to be driven by Cannon.

The current location of Seagroves and Cannon is unknown, and the public is urged not to approach them but to contact New Haven Barracks at 802-388-4919 or provide information anonymously at https://vsp.vermont.gov/tipsubmit.

The Burlington, Essex, Hinesburg, Shelburne, and University of Vermont police departments assisted the state troopers.

No further details have been released, but updates will be provided as the investigation continues.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewson, Dem leaders try to negotiate Prop 47 reform off California ballots, as GOP wants to let voters decide

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoDozens killed near Sudan’s capital as UN warns of soaring displacement

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘Bloody policies’: Bodies of 11 refugees and migrants recovered off Libya

-

Politics1 week ago

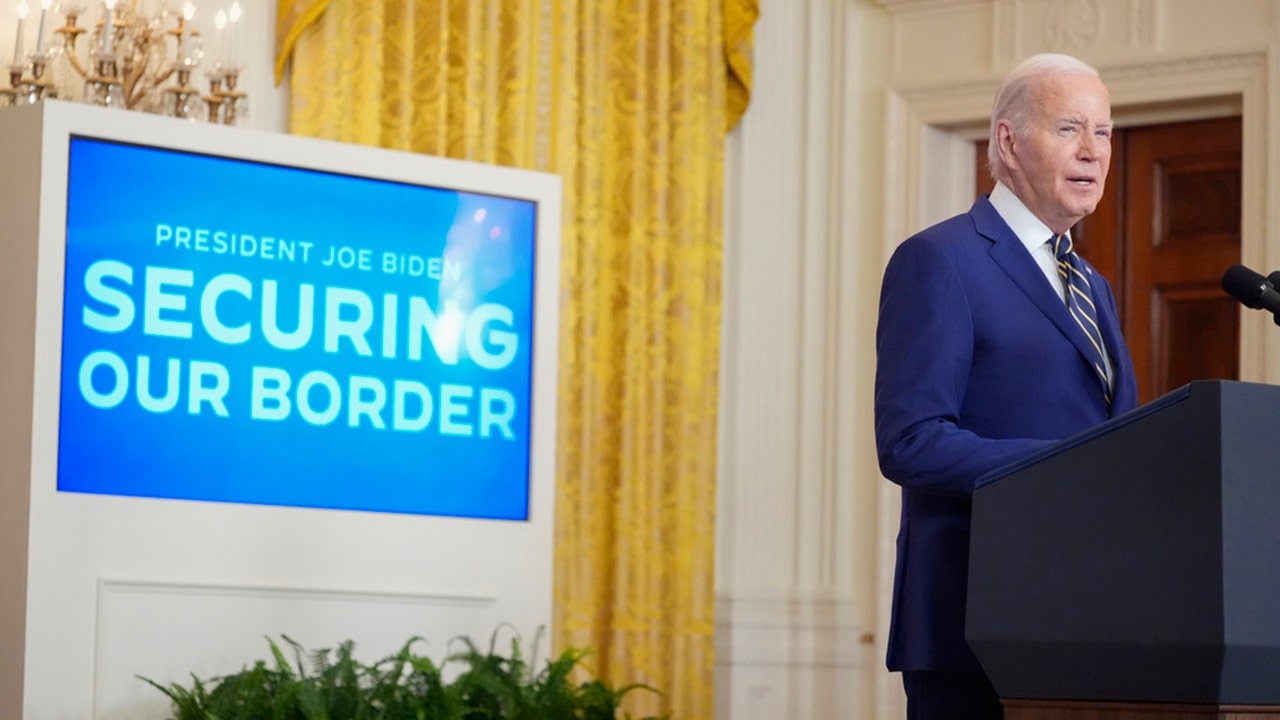

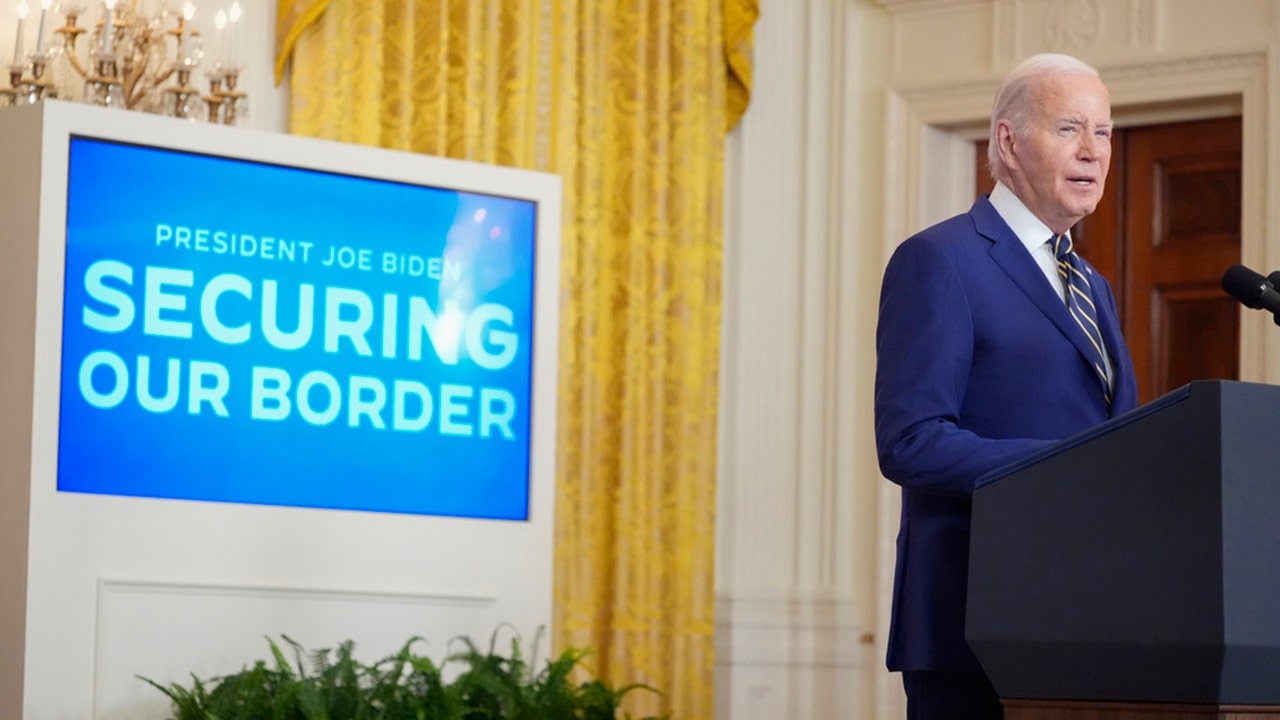

Politics1 week agoEmbattled Biden border order loaded with loopholes 'to drive a truck through': critics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoGun group vows to 'defend' Trump's concealed carry license after conviction

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoShould Trump have confidence in his lawyers? Legal experts weigh in

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWould President Biden’s asylum restrictions work? It’s a short-term fix, analysts say

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead Justice Clarence Thomas’s Financial Disclosures for 2023

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24418649/STK114_Google_Chrome_02.jpg)