Connecticut

Connecticut May Have Figured Out a Way to Halt Executions in Texas

Connecticut abolished capital punishment in April 2012. That made Connecticut the 17th state in this country to do so and the fifth state to end the death penalty after 2010.

Soon, the state will have a chance to do what no other abolitionist state has done. In its next legislative session, Connecticut will consider a bill that would ban the sale of drugs or materials for use in an execution by any business in the state.

Two state legislators, Sen. Saud Anwar and Rep. Joshua Elliott, are leading this effort. As they argue: “This legislation is the logical and moral extension of our commitment to end capital punishment in our state. We do not believe in the death penalty for us here in Connecticut, and we will not support it anywhere else.”

This is not the first time the Nutmeg State has tried to lead the way in the campaign to end America’s death penalty.

At the time it abolished capital punishment, its new law only prevented any new death sentences from being imposed. It left 11 men on the state’s death row awaiting execution.

Three years later, in 2015, the state Supreme Court decided by a 4–3 vote that applying the death penalty only for past cases was unconstitutional. Writing for the majority, Justice Richard Palmer wrote, “We are persuaded that, following its prospective abolition, this state’s death penalty no longer comports with contemporary standards of decency and no longer serves any legitimate penological purpose.”

The court found that it would be “cruel and unusual” to keep anyone on death row in a state that had “determined that the machinery of death is irreparable or, at the least, unbecoming to a civilized modern state.”

With this decision, not only did Connecticut get out of the execution business, but it also appeared at the time that the court’s decision would, as the New York Times put it, “influence high courts in other states … where capital punishment has recently been challenged under the theory that society’s mores have evolved, transforming what was once an acceptable step into an unconstitutional punishment.”

In fact, courts in Colorado and Washington soon followed the Connecticut example. At that point, it seemed that Connecticut’s involvement with the death penalty had come to an end.

Now, Anwar and Elliott are asking the state to again take the lead in trying to stop executions in states where the death penalty has not yet been abolished. The legislation they plan to introduce would, if passed, “prevent any Connecticut-based corporation from supplying drugs or other tools for executions.”

Before examining the rationale for this novel idea, let’s examine why it would be so significant. The recent history of lethal injection offers important clues.

From 1982, when the first execution by lethal injection was carried out, until 2009, every one of those executions proceeded using the same three-drug protocol. It involved a sedative, a paralytic, and a drug to stop the heart.

However, the post-2009 period witnessed the unraveling of the original lethal injection paradigm with its three-drug protocol. By 2016, no states were employing it. Instead, they were executing people with a variety of novel drugs or drug combinations.

The shift from one dominant drug protocol to many was made possible by the advent of a new legal doctrine that granted states wide latitude to experiment with their drugs. This doctrine began with a decision that said that legislatures could take whatever “steps they deem appropriate … to ensure humane capital punishment.”

Subsequently, developments in Europe and the United States made it very difficult for death penalty states to get reliable supplies of drugs for lethal injection. This was the result of efforts by groups like the British anti–death penalty group Reprieve, which launched its Stop Lethal Injection Project and targeted pharmaceutical companies and other suppliers of lethal injection drugs.

Companies selling drugs for executions found themselves on the receiving end of a shaming campaign. As a EuroNews report notes, in 2011, the European pharmaceutical company Lundbeck decided to stop distributing the drug pentobarbital “to prisons in U.S. states currently carrying out the death penalty by lethal injection.”

Later that year, the European Union banned the export of drugs that could be used for “capital punishment, torture, or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” EuroNews explains that “among the drugs that the EU banned in 2011 was sodium thiopental, another drug commonly used in US lethal injections as part of a three-drug method of execution.”

Around the same time, Hospira, an American company that produced sodium thiopental, issued a press release announcing that it had “decided to exit the market.” It did so, according to EuroNews, “amidst pressure from Italian authorities as the company’s production plant was based there.”

In 2016, as the New York Times notes, “the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer announced … that it had imposed sweeping controls on the distribution of its products to ensure that none are used in lethal injections, a step that closes off the last remaining open-market source of drugs used in executions.” That brought to 20 the number of American and European drug companies that have adopted such restrictions, citing either moral or business reasons.

The result was that death penalty states had to improvise to get the execution drugs they needed. As Maya Foa, who tracks drug companies for Reprieve, explained, “Executing states must now go underground if they want to get hold of medicines for use in lethal injection.”

By the end of 2020, states had used at least 10 distinct drug protocols in their executions. Some protocols were used multiple times, and some were used just once. Even so, the traditional three-drug protocol was all but forgotten: Its last use was in 2012.

Other death penalty states, like Alabama, have adopted new methods of execution. A few have revived previously discredited methods. Some, like Ohio, have stopped executing anyone, although the death penalty remains on the books.

This brings us back to Connecticut.

In an op-ed published in April of this year, Anwar and Elliott pointed out that Absolute Standards, a drug manufacturer based in their state, was supplying the execution drug pentobarbital to the federal government and other states. Pentobarbital, either alone or in combination with other drugs, has become a popular alternative to the traditional three-drug cocktail.

“Thanks to Absolute Standards, in his last year in office, Donald Trump was able to end a 17-year hiatus on federal executions and carry out a horrifying spree of 13 executions,” Anwar and Elliott wrote. “The company supplied the Trump administration pentobarbital, a drug that, when used in excess to kill, induces suffering akin to drowning.”

“Absolute Standards,” they explain, “is not a pharmaceutical corporation—it’s a chemical company that makes solution for machines. That’s why it’s flown under the radar since it began producing and supplying lethal injection drugs in 2018.”

Anwar and Elliott’s innovation in the campaign to end capital punishment has already paid dividends. Last week, the Intercept reported that the president of Absolute Standards told the publication that his company had stopped manufacturing pentobarbital.

However, the two legislators are going forward with their plan to introduce their bill during the 2025 legislative session.

As Anwar says, “I think that laws last longer than legislators and issues, and I feel that irrespective of [Absolute Standard’s] commitment, I am interested in having a law in the future … to make sure that we don’t have another similar situation that we learn about indirectly or directly five years, 10 years, 20 years from now.”

Connecticut should adopt the Anwar/Elliott proposal, and legislators in other abolitionist states should follow suit. They should prohibit pharmaceutical corporations, gas suppliers, medical equipment manufacturers, and other businesses in their states from letting their products and services be used in executions. If they do not believe that the death penalty is right for their state, they should not support it anywhere else.

Legislators in abolitionist states should use their power to block businesses from disseminating the instrumentalities of death. They should join Anwar and Elliott in saying, “There is no profit worth a human life.”

Connecticut

Opinion: Connecticut must plan for Medicaid cuts

Three hours and nine minutes. That’s how long the average Connecticut resident spends in the emergency department at any one visit. With cuts in Medicaid, that time will only get longer.

On July 4, 2025, President Donald Trump passed the Big Beautiful Bill, which includes major cuts to Medicaid funding. Out of nearly 926,700 CT residents who receive Medicaid, these cuts could remove coverage for up to 170,000 people, many of whom are children, seniors, people with disabilities, and working families already living paycheck-to-paycheck.

This is not a small policy change, but rather a shift with life-altering consequences.

When people lose their only form of health insurance, they don’t stop needing medical care. They simply delay it. They wait until the infection spreads, the chest pain worsens, or the depression deepens. This is not out of choice, but because their immediate needs come first. Preventable conditions worsen, and what could have been treated quickly and affordably in a primary care office becomes an emergency medical crisis.

That crisis typically lands in the emergency department: the single part of the healthcare system that is legally required to treat everyone, insured or not. However, ER care is the most expensive, least efficient form of healthcare. More ER use means longer wait times, more hospital crowding, and more delayed care for everyone. No one, not even those who can afford private insurance, is insulated from the consequence.

Not only are individual people impacted, but hospitals too. Medicaid provides significant reimbursements to hospitals and health systems like Yale New Haven and Hartford Healthcare, as well as smaller hospitals that serve rural and low-income regions. Connecticut’s hospitals are already strained and cuts will further threaten their operating budget, potentially leading to cuts in staffing, services, or both.

100vw, 771px”/><figcaption class=) Vicky Wang

Vicky WangWhen there’s fewer staff in already short-staffed departments and fewer services, care becomes less available to those who need it the most.

This trend is not hypothetical. It is already happening. This past summer, when I had to schedule an appointment with my primary care practitioner, I was told that the earliest availability was in three months. When I called on September 5 for a specialty appointment at Yale New Haven, the first available date was September 9, 2026. If this is the system before thc cuts, what will it look like after?

The burden will fall heaviest on communities that already face obstacles to care: low-income residents, rural towns with limited providers, and Black and Latino families who are disproportionately insured through Medicaid. These cuts will deepen, not close, Connecticut’s health disparities.

This is not just a public health issue, but also an economic one. Preventative care is significantly cheaper than emergency care. When residents cannot access affordable healthcare, the long-term costs shift to hospitals, taxpayers, and private insurance premiums. The country and state may “save” money in the short term, but we will all pay more later.

It is imperative that Connecticut takes proactive steps to protect its residents. The clearest path forward is for the state to expand and strengthen community health centers (CHCs), which provide affordable primary care and prevent emergency room overcrowding.

Currently, the state supports 17 federally qualified CHCs, serving more than 440,000 Connecticut residents, which is about 1 in 8 people statewide. These centers operate hundreds of sites in urban, suburban, and rural areas, including school-based clinics, mobile units, and service-delivery points in medically underserved towns. About 60% of CHC patients in Connecticut are on Medicaid, while a significant portion are uninsured or underinsured, which are populations often shut out of private practices.

Strengthening CHCs would have far-reaching impacts on both access and system stability. These clinics provide consistent, high-quality outpatient and preventive care, including primary care, prenatal services, chronic disease management, mental health treatment, dental care, and substance-use services. This reduces the likelihood that patients delay treatment until their condition becomes an emergency. CHCs also serve large numbers of uninsured and underinsured residents through sliding-fee scales, ensuring that people can still receive care even if they lose Medicaid coverage.

By investing in community health centers, Connecticut can keep its citizens healthy, reduce long waits, and ensure timely care even as federal cuts take effect.

Access to healthcare should not depend on ZIP code, income level, or politics. It is the foundation of community well-being and a prerequisite for a functioning healthcare system.

The clock is ticking. The waiting room is filling. Connecticut must choose to care for its residents before the wait becomes even longer.

Vicky Wang is a junior at Sacred Heart University, majoring in Health Science with a Public Health Concentration. She is planning to pursue a master’s in physician assistant studies.

Connecticut

Cooler Monday ahead of snow chance on Tuesday

Slightly less breezy tonight with winds gusting between 15-25 mph by the morning.

Wind chills will be in the 10s by Monday morning as temperatures tonight cool into the 20s.

Monday will see sunshine and highs in the 30s with calmer winds.

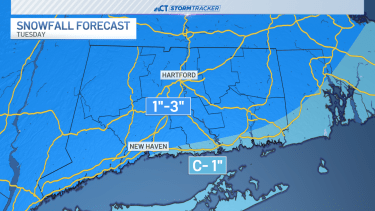

Snow is likely for much of the state on Tuesday, with some rain mixing in over southern Connecticut.

1-3″ should accumulate across much of the state. Lesser totals are expected at the shoreline.

Christmas Eve on Wednesday will be dry with sunshine and temperatures in the upper 30s and lower 40s.

Connecticut

Ten adults and one dog displaced after Bridgeport fire

Ten adults and one dog are displaced after a fire at the 1100 block of Pembroke Street in Bridgeport.

The Bridgeport Fire Department responded to a report of heavy smoke from the third floor at around 3:30 p.m. on Saturday.

Firefighters located the fire and quickly extinguished it.

There are no reports of injuries.

The American Red Cross is currently working to help those who were displaced.

The Fire Marshal’s Office is still investigating the incident.

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoHow much snow did Iowa get? See Iowa’s latest snowfall totals

-

Maine6 days ago

Maine6 days agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoFrigid temperatures to start the week in Maryland

-

South Dakota1 week ago

South Dakota1 week agoNature: Snow in South Dakota

-

New Mexico6 days ago

New Mexico6 days agoFamily clarifies why they believe missing New Mexico man is dead

-

Detroit, MI7 days ago

Detroit, MI7 days ago‘Love being a pedo’: Metro Detroit doctor, attorney, therapist accused in web of child porn chats

-

Maine6 days ago

Maine6 days agoFamily in Maine host food pantry for deer | Hand Off