Longform

Will the 150-year-old Jacob Wirth collapse under the heat, or can it rise from the ashes once again?

Get a compelling long read and must-have lifestyle tips in your inbox every Sunday morning — great with coffee!

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photo via Wikimedia Commons/Biruitorul

It was a total loss from the start.

On June 24, Boston fire crews rushed over to Jacob Wirth, a restaurant on Stuart Street about a block from the Common. News footage showed red-hot flames shooting toward the sky as geysers of thick black smoke choked the night air, transforming the Theater District landmark, known for its old-school German fare and lively atmosphere, into a scene of destruction.

They arrived just before 11 p.m. to battle the four-alarm blaze engulfing the 180-year-old structure, aiming “big lines” and “blitz guns,” according to the Boston Fire Department report. After firefighters were ordered out of the three-story building due to holes in the floor, multiple fire companies stationed on the upper levels of a next-door parking garage and on the street below beat back the flames in both directions.

More than an hour later, the worst of the blaze was over, but firefighters stayed on the scene until 8 a.m. to extinguish hot spots throughout the building, and Stuart Street remained closed to traffic until the early afternoon. When the fire was finally out, the destruction was almost inconceivable. “The bar was pretty much charred from the top down,” said Jamison LaGuardia, vice president of sales and operations at Royale Entertainment Group, who, along with several others, purchased the restaurant in early 2023. The building’s roof was also destroyed—a social media post from the Boston Fire Department on June 25 showed four gaping holes and cracked tiles on the building’s roof—while inside, water from the sprinklers and fire hoses drenched the floors, which then sat damp and moldy for weeks in the summer heat, LaGuardia said. Early estimates put the damage at some $3 million. Though the fire’s cause remains under investigation, one thing was clear: Jacob Wirth had been destroyed.

Oddly enough, this wasn’t the first devastating fire at the property: Shortly after it was put up for sale in June 2018, the iconic German restaurant had burst into flames. (The cause of that fire was listed as “undetermined,” though human involvement was not suspected.) At the time of the second fire, LaGuardia and the rest of the new ownership team were in the process of readying the restaurant for a comeback. In fact, they say, Jacob Wirth was less than three months from reopening—a general manager had been hired, kitchen equipment had been scheduled for delivery, and a new logo had been designed.

Now, it might not be ready for a number of years. “I don’t want to give the impression that we’ve given up. Quite the opposite,” says Jacob Simmons, the vice president of project management at City Realty, another Jacob Wirth owner. Yet speaking in early fall through a palpable sense of frustration and grief, LaGuardia and Simmons struggled to articulate a path forward. Which begs the question: What will become of this celebrated throwback to a Boston long gone?

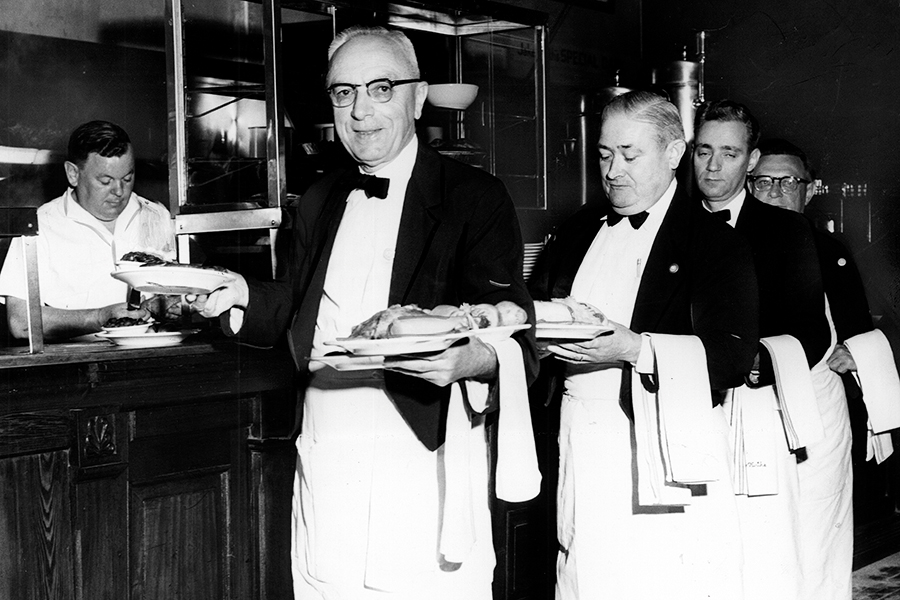

The interior, shown in 2018, changed little over the years. / Photo by Jim Davis/the Boston Globe via Getty Images

An immigrant from the Rhineland, Jacob Wirth arrived in the United States during the 1830s and opened a bar on Eliot Street (now Stuart Street) in 1868. After a decade, he moved his business across the street to its current location. The restaurant drew a diverse clientele, including families, and served unpretentious, steam-cooked German favorites—think herring and sauerbraten—without hurting patrons’ wallets, wrote urban planning scholar James O’Connell in his book Dining Out in Boston. In its early years, the restaurant, operated by Wirth’s relatives until 1965 and purchased by the Fitzgerald family in 1975, offered a male-dominated social environment and appealed to Boston beer drinkers as the city’s first Anheuser-Busch distributor.

German restaurants were particularly attractive to diners searching for new flavors, says Andrew Haley, a cultural historian and author of Turning the Tables, which recounts the story of American restaurants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “After the Civil War in the late 1860s and 1870s, we were increasingly seeing some interest among the general population in culinary adventurism,” Haley notes. “German restaurants became one of the first places that people ventured out to try something a little exotic.”

These were not fine-dining establishments frequented by wealthy city-dwellers, but they offered a rustic experience for open-minded working people who did not mind sometimes eating in a basement. Haley writes about a New York Times journalist who found that in the 1870s, a hearty five-course meal cost just 35 cents at a German restaurant (a little more than $8 today).

Like other cities in the latter half of the 19th century, Boston saw an increase in ethnic and immigrant-owned restaurants that catered to diners willing to expand their palates. A database developed through the Boston College history department shows 13 German-run restaurants in Boston by 1895. “The city [was] becoming more cosmopolitan, not some Yankee port town,” O’Connell says.

But trouble lay ahead for German restaurants in the later half of the 19th century and beyond, as large waves of immigrants from around the world settled in the United States with their culinary traditions in tow, providing American diners with more options for a night out. Between 1870 and 1900, according to the Library of Congress, the United States welcomed almost 12 million newcomers—primarily from Germany, England, and Ireland, but also a sizable population from China. “German food [was] not so much in decline but losing its distinctive spot almost from the moment it became popular,” says Haley, noting that the increasing ubiquity of other cultural foods diminished its popularity.

In the first half of the 20th century, the national ban on alcohol and two world wars dealt three successive blows to German dining. During and immediately following World War I, anti-German sentiment in the United States led German immigrants—at that time the largest non-English-speaking minority group in the nation—to hide their heritage for fear of retribution. American propaganda targeted Germany (“Beat back the Hun with Liberty Bonds”) through posters and flyers; the names of German foods were changed. This virulent strain of nativism included at least one public execution when, in 1918, Robert Prager, a German immigrant and bakery worker who was falsely accused of being a German spy, was hanged on a hackberry tree by a large crowd in southwestern Illinois.

Just two years later, the start of Prohibition dealt a financial blow to German restaurants by depriving them of beer imports. And by the early 1940s, anti-German attitudes were reignited by American involvement in World War II, which led many German Americans to assimilate rather than publicly embrace their heritage.

Here in Boston, though, Jacob Wirth survived, even as it suffered during the 1970s and 1980s due to skyrocketing crime and flourishing adult entertainment in the nearby Combat Zone. As Boston’s de facto red-light district, the heavily patrolled enclave offered prostitution, illegal drugs, and porn theaters while scaring away tourists and families. Sex and stabbings were the currency down Washington Street, and sordid tales of unchecked corruption in what resembled a police state did little to attract diners hungry for Old World cuisine. And yet Jacob Wirth found ways to keep the lights on.

By 1989, city leaders had approved plans to revitalize the Combat Zone, but it didn’t save Jacob Wirth in the long run. Shortly after the Washington Post published a death knell for German cuisine in 2018, detailing a litany of historic German restaurants that had closed their doors in recent years, former Jacob Wirth owner Kevin Fitzgerald announced he, too, was throwing in the towel, placing Jacob Wirth on the market for just north of a million dollars. While Fitzgerald initially cited his divorce as the reason for the sale, it seems as though a perfect storm of personal and financial troubles—including $1.43 million owed to more than 40 creditors—ultimately pushed Jacob Wirth onto the market. Bankruptcy court records show that, by late 2017, Fitzgerald’s Jacob Wirth Restaurant Company owed more than $68,000 in back pay to 25 employees (excluding the more than $10,000 owed to Fizgerald himself). One former restaurant worker filed an affidavit claiming he resigned in 2017 “because Jacob Wirth refused to pay me my wages.” Additionally, court filings reveal that the company owed $412,000 to the IRS, $175,130 to the Massachusetts Department of Revenue, and more than $50,000 in back rent.

Coupled with the June 2018 fire while the property was still on the market, it seemed like the end of Jacob Wirth. Then, last year, a group of six business partners and real estate investors came to the rescue, purchasing the beleaguered restaurant. City Realty, a Boston real estate firm, was charged with construction and development, while Royale Entertainment was set to run operations. The team was in the middle of renovations when the second fire tore through the property, giving it the distinction of being perhaps the unluckiest restaurant in Boston.

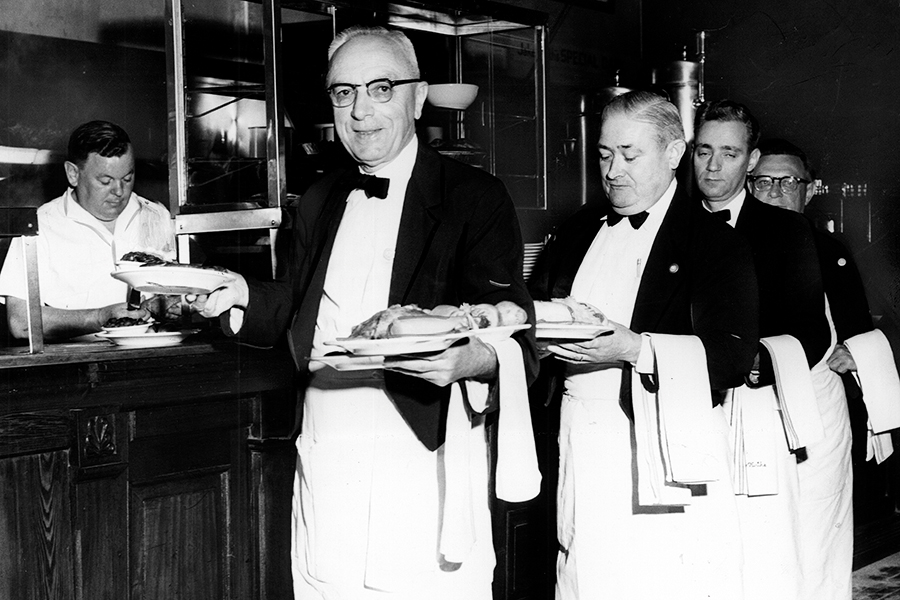

Jacob Wirth was a bastion of German cuisine in the 1950s. / Photo by Bill O’Connor/the Boston Globe

Even if the new ownership team does manage to rebuild, another question looms large: Could Jacob Wirth ever shake off the dust—both literally and metaphorically—to reclaim its spot as a cultural force in the city? Some food historians aren’t so sure. Haley believes that while there is some taste for more-modern German food among the public, Jacob Wirth would likely struggle trying to re-create what it once was. After all, says former Boston restaurant critic Corby Kummer, now a senior editor at the Atlantic and executive director of food and society at the Aspen Institute, “What Jacob Wirth had that made it so valuable was atmosphere. This old-time urban bar setting: rough and ready, hearty and fun.”

If, and when, it ever reopens, Jacob Wirth would not be the only game in town for German fare, though quality options remain few and far between. Bronwyn, a German and Central European–inspired eatery in Somerville’s Union Square, was opened in May 2013 by award-winning chef Tim Wiechmann and his wife, the restaurant’s namesake. Meanwhile, Karl’s Sausage Kitchen, a European grocer and Peabody institution since 1958, has weathered a national downturn in public demand for German cuisine by offering high-quality products and emphasizing authenticity, says co-owner Anita Gokey. “We have really stayed true to the German sausage-making traditions,” she explains.

Gokey, who co-owns Karl’s with her husband, welcomes regular customers from all over New England: German immigrants who still cook traditional fare, the descendants of German immigrants who remember bratwursts and frankfurters from their childhoods. But the art and labor of sausage-making is hard to pass on, she says, and a controversial Massachusetts law banning the sale of pork from pigs kept in tightly confined spaces has negatively affected food costs. “It’s like death by a thousand cuts between all of the expenses, the regulations, and the labor costs,” she says.

Despite the financial and cultural challenges, the owners of Jacob Wirth are resolute about reopening someday, believing there is still public demand for the restaurant. “People have reached out over the past year and a half to say how important [Jacob Wirth] was to them, that their grandfather was an original waiter, or that their parents had their first date there,” LaGuardia says. “People have so many memories, and it’s such a staple in the Boston scene that it’s made it more personal for us.”

The aftermath of this summer’s devastating fire. / John Tlumacki/the Boston Globe via Getty Images

Indeed, Reddit threads attest to the nostalgia many Bostonians feel for the dining institution. “NO!!! NOT JACOB WIRTH!!!” one person posted shortly after the fire. “This one hits hard.” Replied another: “I bike down Stuart Street on my way to work and was devastated to see all the windows blown out this morning. It’s such a beautiful building and an important piece of history, but I’m afraid this might be the last nail in the coffin. Feels like a stretch, but I hope it still comes back someday.”

A spokesperson from the city’s Office of Historic Preservation issued a statement that Boston is committed to rebuilding Jacob Wirth and working alongside architects, historians, and the current owners. The office described the “cherished Boston landmark” as an essential part of city history, an institution that “represents the legacy of generations who have contributed to the cultural and architectural tapestry of our city.”

Still, make no mistake: Reviving the restaurant demands deep pockets and a monumental effort—a daunting task that leaves many Bostonians hoping the elusive dream of Jacob Wirth hasn’t gone up in smoke forever.

First published in the print edition of Boston magazine’s November 2024 with the headline, “The Bierhaus That Burned Down. Twice.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25299201/STK453_PRIVACY_B_CVirginia.jpg)