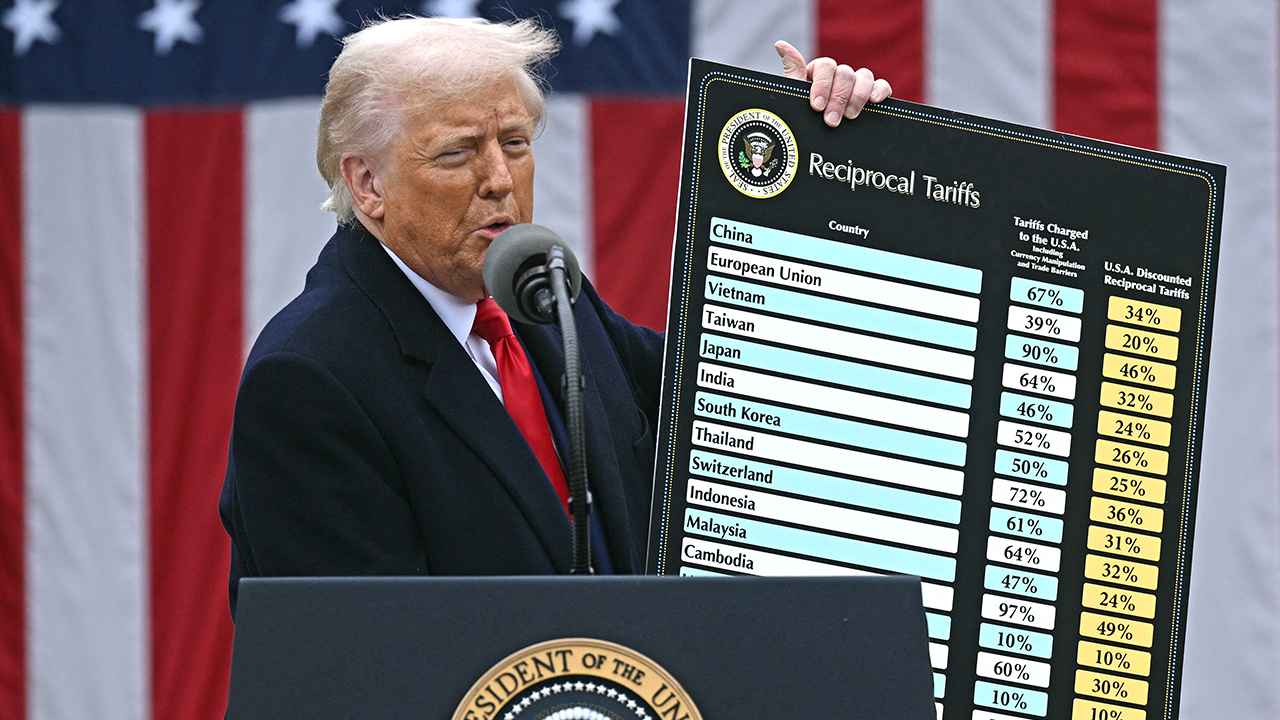

Well, at least we now know what Donald Trump will do with tariffs, until he is seized by another whim. Perhaps it was better when we didn’t. The “reciprocal” tariffs announced on so-called liberation day were farcical, set by an arithmetic formula based on trade deficits in the apparent belief that current account imbalances can be fixed by trade policy.

The US will apparently charge tariffs on exports from Heard Island and the McDonald Islands, a volcanic archipelago near the Antarctic inhabited only by penguins, and from Diego Garcia, a US military base. In theory tariffs trigger a currency appreciation to offset their effects but the dollar has weakened in response to this shambolic policymaking.

But this isn’t some general crisis of credibility in trade and globalisation. It’s largely a localised pathology, and particularly one of the Republican Party. The Democrats under Joe Biden accepted far too much of Trump’s first term tariff legacy, but at least with a vaguely coherent industrial policy rationale. The Republicans haven’t necessarily turned into a seething nest of protectionists, but their increasingly extreme bent ever since Richard Nixon took the party to the right in the 1960s has allowed a mindlessly destructive trade warrior to take over and they are too terrified to stop him.

Accident, prejudice and unintended consequence play a bigger role in dysfunctional US tariff policy than the grand sweep of economic history might suggest. The “Tariff of Abominations” in 1828, which massively raised taxes on industrial imports, almost causing South Carolina to secede from the union because of the effect on agricultural trade, became law by accident. Lawmakers from southern farming states inserted destructive spoilers to prevent it being agreed and watched with horror as it passed nonetheless.

The notorious Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1930 similarly reflected politicking gone wrong. This time, Republicans proposed big industrial tariffs, which US manufacturers didn’t need, as a quid pro quo for introducing protection for farmers. They did not imagine that other countries would retaliate and set off a global spiral of protection that worsened the Great Depression.

This current case is not just a tactical mistake: it’s what happens when an ideological extremist becomes president. If there are any grown-ups among Trump’s economic team, they are locked in a cupboard when decisions are taken. Among them is Kevin Hassett, an orthodox free-trade economist who advised George W Bush and Mitt Romney but who is unable or unwilling to stop the chaos. Treasury secretary Scott Bessent was supposed to be the voice of the financial markets: he’s evidently silent or ignored. The animating drive is from Trump himself, who since the 1980s has had a wrong-headed view of tariffs based on an analogy with a corporate profit-and-loss account, and the trade warrior Peter Navarro, who appears closest to the president’s ear.

Under a president of the Bush mould, many of today’s congressional Republicans might well be willing to preserve a relatively open trading system. John Thune of South Dakota, elected as majority leader of the Senate in November, holds orthodox views on the need for more trade deals to open up markets abroad. But along with almost all his caucus, he has utterly failed to reassert Congress’s constitutional role in trade policy.

The consolation is that the rest of the world is much less likely to follow the US than it did in the 1930s, during which time the international gold standard was also inflicting profound damage and inducing extreme reactions from policymakers. Only the EU is likely to retaliate with tariffs and other import restrictions anywhere near dollar for dollar, and Brussels emphatically does not want to raise high and permanent trade barriers with the rest of the world.

The US is a smaller share of the global economy than during the 1930s, and the risks of protectionism are far better understood. In the same way that Trump has kindled Canadian public patriotism and a geopolitical awakening among European leaders, his tariffs are more likely to act as a cautionary tale for other governments than an incentive to join the US in some fantastical “Mar-a-Lago Accord” to realign currencies.

There can be no logic-washing of Donald Trump’s tariffs. This isn’t part of a carefully-designed industrial policy or a cunning strategy to induce compliance among trading partners or a choreographed appearance of chaos to scare other governments into obedience. It’s wildly destructive stupidity, and the generations of American, and particularly Republican politicians, who allowed things to slide to this point are collectively to blame.

alan.beattie@ft.com