North Dakota

Citizens wage David vs. Goliath fight to save Bismarck-Mandan rail bridge

Editor’s note: This is the first of the three-part series called “Battle for the Bridge,” chronicling efforts to spare the Bismarck-Mandan rail bridge from demolition.

BISMARCK — The geometric trusses of the railroad bridge spanning the Missouri River have served as a popular backdrop in photographs for years, providing a scenic background for graduation pictures, wedding photos and promotional images.

The 140-year-old bridge is not only iconic, but historic. It was built in the 1880s, when Bismarck was a raw town on the Dakota Territory frontier.

Bismarck’s history, in fact, is enmeshed with the railroad. It originated in 1872 as Camp Greeley, a military post to protect the Northern Pacific Railway as it pushed west toward the Pacific Coast.

Troy Becker / The Forum

In one whirlwind week in September 1883, soon after the bridge opened, notable figures including Sitting Bull, a young Theodore Roosevelt, then-President Chester Arthur and former President Ulysses S. Grant rode trains across the bridge.

But the iconic bridge’s days appear to be numbered. BNSF Railway, the successor to the old Northern Pacific, has declared that the bridge has reached the end of its useful life and wants to tear it down, replacing it with one capable of supporting two sets of tracks.

The railroad’s plan to dismantle the bridge, announced in 2017, has provoked a citizen campaign,

led by a group called Friends of the Rail Bridge,

to save the historic structure.

It’s a decidedly David vs. Goliath battle, with the preservation group taking on a corporate behemoth with $92.6 billion in assets and more than 36,000 employees.

So far, BNSF is getting its way. The railroad has secured all of the federal and state permits required to build the replacement bridge and, once finished, tear down what was the first bridge to cross the upper Missouri River — a span that played a crucial role not only in opening western Dakota Territory for settlement, but the Pacific Northwest as well.

“I’d argue it’s the most historically significant standing structure on the Northern Plains,” said Erik Sakariassen, a leader of Friends of the Rail Bridge. “There’s a lot of reasons why it became extremely important.”

The bridge played a crucial role in the cutthroat bid to move the territorial capital from Yankton to Bismarck, an event that contributed to the breakup of Dakota Territory into North Dakota and South Dakota, he said.

“Basically, it opened up settlement of the Northwest,” said Ann Richardson, another leader of Friends of the Rail Bridge. “The idea that it’s just another bridge is wrong. To America, this was an extremely significant bridge.”

The bridge’s precarious position is made clear by the cranes looming nearby, poised to begin construction on the $100 million replacement once the last obstacle is removed.

Darren Gibbins / The Bismarck Tribune

Now, all that stands in the way of the end of the historic bridge is a legal challenge by the Friends of the Rail Bridge, which doesn’t object to the new bridge but is pleading for the old bridge to be spared.

A court proceeding that could determine the fate of the historic bridge is set for Thursday, Nov. 16, when the North Dakota Supreme Court will hear arguments over the contested state permits for the project.

Crossing the ‘mighty Missouri’

The birth of the Missouri River bridge between Bismarck and Mandan, a vital crossing in the first transcontinental railroad across the nation’s northern tier, had its origins with a stroke of Abraham Lincoln’s pen.

In 1864, Lincoln signed legislation making available a massive federal land grant to finance the undertaking — a law granting 40 alternate sections of land per mile in the Dakota, Montana and Washington Territories and 20 alternate sections per mile in Minnesota and Oregon.

A few years later, the newly created Northern Pacific Railway Co. bought the charter and gained access to enormous land holdings, providing not only the rail corridor but surplus lands that could be sold to finance construction.

The settlers who followed the tracks bought much of that land, linking remote areas to the rest of the country.

In 1871, the Northern Pacific Railway started laying track eastward from Kalam, Washington, and westward from near Duluth, Minnesota.

By 1872, the track reached what became Bismarck. Then, in 1873, a financial panic caused a depression, thrusting many businesses into bankruptcy and halting construction of the Northern Pacific, leaving Bismarck as the eastern terminus of the incomplete rail line.

The Missouri River between Bismarck and Mandan posed a formidable challenge, one described by the Northern Pacific in a promotional advertisement as:

“Almost equivalent to scaling and tunnelling great mountain ranges to construct the ‘First of the Northern Transcontinentals’ was the bridging of the mighty Missouri, greatest river barrier of the Northwest.”

Bridge builders watched the migrating bison and “confidently located the vital structure where the great herds swam the stream,” the Northern Pacific ad said.

Before the bridge was built, the frozen Missouri became a “bridge of ice” during the frigid months of January and February from 1879 to 1881, with tracks laid across the river to enable trains to cross with supplies.

In the warmer months, transfer steamboats were used to ferry goods and supplies across the river.

The Northern Pacific made a seemingly unconventional choice by hiring a self-taught engineer to design the bridge.

George Shattuck Morison was a Harvard-educated lawyer whose only formal engineering training was in general mathematics.

But he had an aptitude for mechanics and became a civil engineer who specialized in steel truss bridges.

Morison’s choice for the bridge’s location was logical: It provided the shortest route between tracks that had been laid on both sides of the river.

Contributed / Library of Congress

The river’s wide channel — 3,000 feet — was long for a bridge, so starting in July 1880 Morison had workers build a dike to narrow the river. Crews hauled in 33,000 tons of rock scavenged from the prairies surrounding Bismarck and Mandan.

One of the most daunting construction challenges was building two stone support piers within the river.

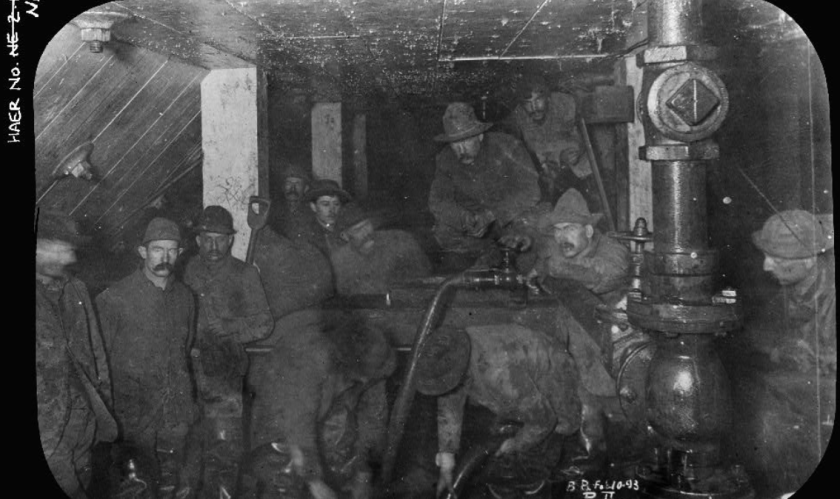

To accomplish that, workers built airtight wooden chambers called caissons, equipped with iron edges on the bottom to help seat them in the muddy river bottom. Steamboats towed the caissons into place and sunk them.

Air compressors kept the chambers dry and ran pumps to suck loose sand from the caisson floor. Working by the light of lanterns and torches — a risk since the chambers were sealed with flammable caulk sealant — workers used picks and shovels to excavate the claystone bottom.

Workers faced another hazard: formation of nitrogen gas bubbles in their bloodstream whenever they moved abruptly from the pressurized chamber to normal atmospheric pressure onshore, a decompression sickness called “the bends” because of its effects on the limbs.

Contributed / Library of Congress

A number of workers died or suffered permanent injuries, according to a history of the bridge written by Ed Murphy, the state geologist whose interest in the bridge grew out of the longstanding soil instability problems on the river’s east bank.

Workers completed major construction of the bridge on Oct. 18, 1882. Three days later, engineers tested the bridge’s structural soundness. A crowd of thousands watched as the deflection of eight locomotives was measured.

When the test was successfully completed, the locomotives blew their whistles. Guests from around the country gathered for a luncheon at the InterOcean Hotel in Mandan and later that evening at the Sheridan House in Bismarck.

After completing the finishing touches, including painting, the contractors turned the bridge over to the Northern Pacific Railway on Aug. 1, 1883.

Contributed / Library of Congress

Former President Grant crossed the rail bridge on Sept. 5, 1883, after participating in laying the cornerstone for the new territorial capitol in Bismarck, an event the Northern Pacific had reason to celebrate.

Sitting Bull — whose Hunkpapa Lakota fought ferociously to keep the railroad out of their bison-hunting grounds — also attended and rode the train across the river from Mandan.

Grant was among the dignitaries who traveled west in a VIP train car to attend the “last spike” ceremony at Gold Creek, Montana Territory, signifying the completion of the Northern Pacific railroad, on Sept. 8.

Contributed / State Historical Society of North Dakota

The day before, on Sept. 7, young Roosevelt crossed the Missouri River rail bridge en route to the Little Missouri Badlands, where he went to hunt bison, whose numbers were rapidly dwindling due in no small part to the arrival of the railroad.

BNSF Railway’s announcement in 2017 of its plans to replace the historic rail bridge caught Bismarck and Mandan by surprise.

Residents recoiled at the plan to demolish the bridge, so much a part of the twin cities’ history and identity.

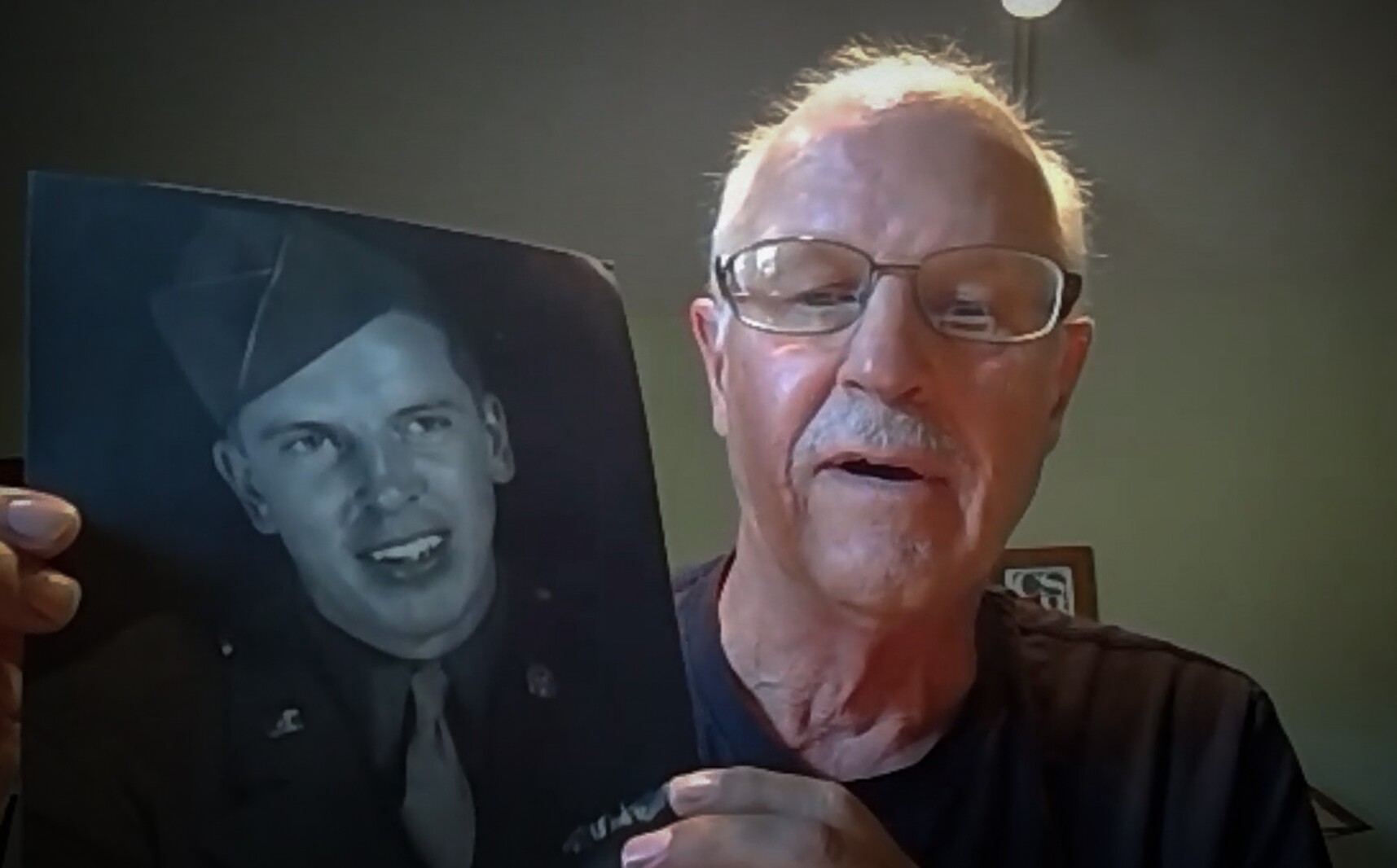

Contributed / Marshall Lipp

The North Dakota State Historic Preservation Office agreed that the bridge is “eligible for the National Register of Historic Places,” meaning it has historic significance.

A diverse band of citizens joined together in 2018 to form Friends of the Rail Bridge, a nonprofit organization with the mission of presenting an alternative to preserve the old bridge.

The preservation group commissioned a study from the North Dakota State University architecture department’s landscape architecture program to explore turning the rail bridge into a pedestrian bridge that could connect to recreational trail systems on both sides of the river.

In 2019, the rail bridge was placed on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of America’s 11 most endangered places for the year.

The NDSU team estimated in 2019 that conversion would take 14 months and cost $6.9 million. Friends of the Rail Bridge have proposed that the pedestrian bridge could be part of a recreation and entertainment complex that also includes new riverfront developments in Bismarck, including its Heritage Landing and Gateway to Science building.

Other proposed features include a potential boardwalk and beach area at the site of Keelboat Park, an amphitheater or a riverfront hotel near Steamboat Park.

“Allowing this bridge to be demolished when there are so many opportunities for riverfront development is inconceivable,” said Margie Zalk Enerson, a member of Friends of the Rail Bridge.

Efforts to save the bridge resulted in an agreement in 2021 shaped with the involvement of the U.S. Coast Guard, which has federal permitting authority for the bridge project, that spelled out interested parties and concrete steps that would have to be taken.

But the planned agreement unraveled. Among other problems, the preservation group was unable to sign up a crucial governmental partner, state or local, so it was unable to present a plan showing preserving the bridge was technically and economically feasible, in the judgment of the State Historic Preservation Office.

“While we are saddened by these developments,” Bill Peterson, the state’s historic preservation officer wrote in June 2021, the time had come to “address removal of the bridge.”

After a three-year review, the U.S. Coast Guard determined in December 2022 that the rail bridge “is approaching the end of its useful life and needs to be replaced.” The best option, federal officials concluded, is to build a new bridge about 20 feet upstream and to remove the old bridge.

Friends of the Rail Bridge argues that the old bridge could be spared by building the new bridge 92.5 feet upstream.

The state of North Dakota, meanwhile, appears resigned to the fact that the historic bridge will be coming down.

In early 2023, the North Dakota Department of Water Resources granted state permits allowing BNSF to build a new bridge and demolish the old bridge, although the preservation group is challenging those permits in court.

On Sept. 27, the State Historical Society of North Dakota announced that it had selected three organizations to salvage parts of the old bridge through a $500,000 BNSF Railway grant provided under an agreement with the U.S. Coast Guard.

The grant will pay to create an exhibit about the rail bridge at the North Dakota Railroad Museum in Mandan, a series of videos and the display of salvaged remnants of the old bridge to be featured in a plaza in Mandan.

Come back to InForum for part two of the “Battle for the Bridge” series, which will cover how Gov. Doug Burgum’s office gradually backed away from preserving the bridge, a move which preservationists said was devastating blow to their efforts.

North Dakota

Enrollment up nearly 4% at North Dakota public colleges, universities

BISMARCK, N.D. (Jeff Beach/North Dakota Monitor) – Fall enrollment at North Dakota University System campuses is up nearly 4%, the highest enrollment recorded since 2014.

The 11 public colleges and universities have 47,522 students, according to figures released Wednesday. The system’s record enrollment was in 2011 at 48,883.

Williston State College saw the highest percentage growth in headcount with 11%, while North Dakota State College of Science reported a 9% enrollment jump, Bismarck State College reported an 8% increase and Mayville State University reported 7% growth.

The University of North Dakota, which leads the state in enrollment, saw a 5% increase and is at an all-time high with 15,844 students.

UND President Andy Armacost said the university has seen strong growth in new students the past two years.

“We’re grateful to be able to impact a large number of students with the great programs at UND,” Armacost said.

Bismarck State College’s enrollment of 4,549 students also was a record.

“Seven straight semesters of growth show that our polytechnic mission is not only resonating but making a real difference for students and the industries we serve,” Interim President Dan Leingang said in a statement.

North Dakota State University has recorded the exact same fall headcount for the past three years at 11,952 students. NDSU showed a 3% increase in first-year students, alongside a significant rise in new international undergraduate students, according to a news release from the university.

NDSU has 95% of students enrolled in in-person programs, the highest number across the entire North Dakota University System, the release said.

NSDU President David Cook, who is in his third year on the job, appeared remotely before a North Dakota legislative committee Wednesday.

“We have stabilized enrollment at NDSU, and I think we’re creating the right foundation for where we want to be,” Cook said.

Minot State University President Steve Shirley, in a Tuesday presentation to the State Board of Higher Education, said that while headcount at the school is flat, there is a 3% increase in full-time equivalent students that he said reflects a “nice little bump” in freshman enrollment — about a 15% increase.

“We’re excited about that,” he said.

Dickinson State University was the only school to show an enrollment decline, down 3%.

Dakota College at Bottineau had 3% enrollment growth. Lake Region State College and Valley City State University each reported 1% increases.

North Dakota

Board approves Brent Sanford as new ‘commissioner’ of North Dakota University System

MINOT — The board overseeing the North Dakota University System has awarded the interim chancellor the permanent role and changed the name of that role in the process.

The State Board of Higher Education unanimously approved Brent Sanford as commissioner of the system at its meeting Tuesday, Sept. 23, in Minot.

Sanford, a former Republican lieutenant governor, was

named the interim university system leader in April,

replacing Chancellor Mark Hagerott,

who stepped down around the same time.

In August, Board Chair Kevin Black told a legislative committee meeting in Dickinson that

he favored skipping a nationwide search in favor of giving Sanford the job.

Before the vote Tuesday, Black called it a “once-in-a-generational opportunity” to appoint Sanford, whom he said can make a true difference for higher education.

“For those reasons, I think doing the right thing and putting the right person in the seat trumps the process. In this case, I think it is absolutely 100% worth it,” Black said.

Other board members praised Sanford, indicating he was an obvious choice.

“I can always recognize the guy that’s got that ‘it factor,’ and in my opinion, Brent’s got that ‘it factor,’ and I’m excited about his opportunities to come and lead this university system,” said Member Tim Mihalick.

Said Member Danita Bye, “We could have done a national search and Brent would be our top candidate.”

Black said despite changing the title to commissioner, a motion that also received unanimous approval, the role of the position does not change.

“What I think the board is really saying through this motion is that we believe it’s important to align with what the Constitution says and what Century Code says,” he said.

To reflect the change, Board Vice Chair Donald “D.J.” Campbell laid out further amendments to other leadership titles.

The chancellor will become commissioner, the vice chancellor for academic and student affairs will become deputy commissioner/chief academic and student affairs officer, and the vice chancellor for administrative affairs will become deputy commissioner and chief financial officer, he said.

Before the vote on Sanford took place, he gave a presentation to the board and answered questions from board members.

Member Patrick Sogard asked about

a perception among some in the public

of Sanford’s lack of experience in academia.

Hagerott, who had led the university system since 2015, had a doctorate degree, and other recent chancellors have had master’s or other advanced degrees.

Sanford said his experience interacting with higher education as lieutenant governor was valuable.

He added that he was truly enjoying the role as interim chancellor.

“You can probably tell I do and I find it a better fit than I thought it would be, because it’s turning out that this job is very much a government leadership, government administrator, political administrator, type job that I’m used to,” Sanford said.

Also slated to be discussed Tuesday was

consideration of a policy change stating presidential vacancies at colleges and universities may be filled without doing a search.

North Dakota

One Up for the North Dakota Teacher’s of the Year is From the Grand Forks District

Emily Dawes. (Photo provided by the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction)

(KNOX) – A literacy specialist for grades kindergarten through fifth at Lake Agassiz Elementary School in the Grand Forks District, Emily Dawes is one of four finalists for North Dakota Teacher of the Year.

“I somehow was nominated. I hope it was a reflection of me as a teacher. So than I was chosen from a committee, so a committee chose me.” Dawes told KNOX News in an interview.

Dawes was a teacher at J. Nelson Kelly Elementary School when she was named as a contender for teacher of the year.

“I was at Kelly Elementary and I was happily teaching first grade and I absolutely loved every moment of it. But this opportunity to be a literary specialist came my way,” said Dawes.

The winner will be named in ceremony on September 26th in Bismarck.

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoReimagining Finance: Derek Kudsee on Coda’s AI-Powered Future

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoSyria’s new president takes center stage at UNGA as concerns linger over terrorist past

-

North Dakota1 week ago

Board approves Brent Sanford as new ‘commissioner’ of North Dakota University System

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoThese earbuds include a tiny wired microphone you can hold

-

Culture7 days ago

Culture7 days agoTest Your Memory of These Classic Books for Young Readers

-

Crypto7 days ago

Crypto7 days agoTexas brothers charged in cryptocurrency kidnapping, robbery in MN

-

Crypto1 week ago

Crypto1 week agoEU Enforcers Arrest 5 Over €100M Cryptocurrency Scam – Law360

-

Rhode Island1 week ago

Rhode Island1 week agoThe Ocean State’s Bond With Robert Redford