Lifestyle

In the vastness of the desert, there are so many ways to fly

“And Her Return Will Be Wonderful,” from “Dreaming Gave Us Wings,” 2020

(Sophia Nahli Allison)

This story is a part of Picture concern 8, “Abandoned,” a supercharged expertise of turning into and religious renewal. Benefit from the journey! (Wink, wink.) See the complete package deal right here.

I haven’t actually even instructed this story to anybody. I nonetheless do have goals of flight.

I don’t assume I might have had that language as a child to explain the way it occurred precisely. It was extra a couple of sensation. A psychological idea. I needed to be concentrated and centered. I needed to be on this deep meditative state. The second I misplaced focus, it could utterly disappear. It was like an astral projection, you understand. Our sphere of having the ability to depart our physique for a while. I might simply be capable of create this sensation of my mattress utterly taking off the ground.

Me, simply flying.

It’s not like that anymore. There was an age when it utterly stopped. And I used to be by no means ready to do this once more. Nonetheless, I keep in mind how my goals of flight have been how I found that I might exist in a means that I wasn’t allowed to in my on a regular basis life. Desires felt like this place the place I could possibly be protected, the place I could possibly be who I wished to be, the place I could possibly be my full self. I might take away all these obstacles that saved me confined and be as free and as adventurous as I wished to be.

In my goals, I’m capable of fly away when I’m in a scenario that I have to get out of, a scenario that doesn’t really feel protected, that I don’t get pleasure from. After I don’t need to be round, I’m able to utterly launch my physique and fly away. That’s what I’ve found in goals. Easy methods to liberate myself. Easy methods to free myself.

I feel it most likely was listening to tales of flying as a younger lady. Understanding the story of flying Africans, being conversant in them by Toni Morrison and Virginia Hamilton. Octavia Butler begins off “Parable of the Sower” with the lead character, Lauren, speaking about herself flying in goals. It made me so joyful to find that at any time when a Black lady talked about flight, she was utilizing flight as a coded language for self-liberation. Realizing it was a dialog woke me up in a means.

How do I do it? How do I fly? Toni Cade Bambara as soon as instructed fellow author Akasha Gloria Hull: “It’s solely air.” Truthfully, I don’t inform anybody how I do it. I’ll say my physique is the location of reminiscence. I’m permitting myself to be led by spirit. I’m a conduit.

::

Joshua Tree, 2021, by Sophia Nahli Allison.

(Sophia Nahli Allison)

I‘ve typically discovered that including little bits and items of magic in my very own life is admittedly therapeutic for me. It’s how I envision the world. It’s how I see. I would like spirit to be a component of my documentary work as a result of there is no such thing as a tangible proof that any such realm can exist to some folks. Black people, Black lady, Black queer people — in our oral historical past, we have now all the time integrated these parts of spirit, these parts of radical creativeness. Because the filmmaker, I all the time need these parts to be part of the story.

I’m curious what the religious realm seems like. I simply need folks to query:

What does it seem like to exist in a number of realms without delay?

What occurs once we don’t have proof of the story?

How can we reimagine what that story seems like?

How can we reimagine what the religious archive is?

How can we have interaction with ancestors?

How can we have interaction with reminiscences?

How can we have interaction with our goals?

What does the nontangible seem like?

What does therapeutic seem like and really feel like?

How can we permit our creativeness to be expansive?

Am I in a dream or am I in actuality?

If it seems like a dream, why can’t or not it’s a reality as properly?

I take into account myself an experimental filmmaker and photographer as a result of I’m all the time exploring the way to blur the traces between actuality and fiction. In a variety of my movie work, I need to break down conventionality and discover new methods to inform tales. What does that second seem like between waking and sleeping? I all the time need my work to really feel a bit ethereal. It’s a means of conjuring. It’s taking moments of the on a regular basis, of the mundane, and discovering these magical and religious parts that exist and reside round us.

I’m actually impressed by the work of author Zora Neale Hurston, who typically blended these traces — Right here’s folklore. Right here’s our reality. Right here’s my historical past: That is what I’m going to withhold; that is what I’m going to inform. I grew up listening to a variety of folklore and realized that it was one thing that spoke to me deeply. It spoke to who I used to be in my non-public moments. It spoke to how my creativeness would run wild, what issues I needed have been true, what issues I needed I might expertise. As a filmmaker or a photographer, I don’t must compartmentalize what folks assume is reality and what folks assume is folklore. I can let each exist in the actual world with us. It’s not like I’m in any respect altering the reality — the recorded reality is there. However I’m additionally including a brand new reality to the archive that hasn’t been there earlier than.

I don’t know the way to do it some other means.

::

I keep in mind after I was beginning off. I taught myself images. I went to high school to check photojournalism as an undergrad at Columbia School Chicago, after which I studied documentary filmmaking in grad college on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I discovered myself making an attempt to emulate what I noticed everybody else doing. That is how documentary ought to exist, I assumed. That is what qualifies as photojournalism. I all the time wished to be an artist, however I simply didn’t really feel I had the time or the right coaching to name myself one. It was safer to name myself a documentarian, or a visible journalist, as a result of I didn’t have the {qualifications} to be thought-about an artist. That was my very own work idea that I needed to unlearn and develop out of.

I spotted I used to be not a photojournalist after I was doing an internship. I used to be sitting in my automobile, deciding if I ought to take time without work from grad college, transfer again to L.A. and take this job working in movie. I had a panic assault. I used to be like, I don’t get pleasure from photojournalism. There is no such thing as a freedom. It’s rooted within the white gaze. I’m actually surrounded by white supremacist ideology. I actually should be free from this.

In documentary, you’re supposed to stay goal, however objectivity just isn’t one thing I actually consider in. As a Black, queer lady, there’s no means I can disconnect myself from my expertise and the experiences of those that seem like me and who transfer by the world like me. In two of my documentary initiatives — “A Love Track for Latasha” and “Eyes on the Prize: Hallowed Floor” — I began to know that I wanted to place myself into the work, each bodily and spiritually. It’s so essential to ensure that the way in which by which I inform tales by documentaries is genuine. As a Black lady, it’s essential that I’m archived.

I grew up round artists in Leimert Park and Jefferson Park. My dad was a musician; my mother, a storyteller. My mother would carry out in Leimert — on the library, at museums and colleges — and I might be a part of her and her group of storytellers now and again. Alice Walker, in her seminal essay “In Search of Our Mom’s Gardens,” requested: “What did it imply for a Black lady to be an artist in our grandmothers’ time? It’s a query with a solution merciless sufficient to cease the blood.” So typically Black girls don’t have the assets, the help, the company, the liberty, to be an artist. My mother made all of her personal props and costumes. I typically witnessed her in the home, performing and training. It was so inspiring to me to see a Black lady protecting artwork alive for herself.

Plenty of her tales primarily have been tales of the diaspora, tales of the Black South and Black life, tales of her reminiscences from childhood. Primarily, it was a variety of folklore. I keep in mind studying “Anansi the Spider,” which enchanted me as a younger lady.

My mom opened up a world of folklore, an oral custom, that piqued my curiosity. One such story I realized was Virginia Hamilton’s “The Individuals May Fly.” “The Individuals May Fly” is so digestible for a narrative that’s truly rooted in trauma. I really like the way it depicts some Black people who’re left on the plantation and others who’re capable of fly away. Simply because an individual is Black doesn’t imply they will fly. That’s actually essential to notice — what does it imply to fly? Properly, it’s a must to get up to a sure consciousness. There’s a type of rebirth in it; there’s a type of We’re going to reclaim this company over our life. I really like the way it’s offered for Black youngsters to know this folklore, to know this chance and this historical past. That was my earliest understanding of storytelling — that there are these worlds that exist that aren’t documented as our waking world, however there’s a reality contained in these worlds.

::

Summer time 2020: My girlfriend and I drove throughout the nation from North Carolina to L.A. I had been dwelling in North Carolina for a few years and was extraordinarily homesick. And we have been like, “Let’s return.” On the drive, I keep in mind seeing the panorama change. The desert, the mountains — I began getting the sensation, That is my return dwelling.

The desert represents rebirth. It’s a panorama that you simply don’t anticipate to see be fertile. You don’t anticipate to see issues develop from it. However that’s what’s so stunning. It’s not lifeless. There’s a lot life right here. I all the time assume, What are these Joshua timber saying? I ponder about these voices — the sounds the mountains of the desert make, the spirits that exist. I really like how quiet the desert is. The wind has such a character.

I like to talk to the universe after I’m within the desert. I like to only communicate out loud. Nobody can hear you. Nobody. I can simply say the phrases I have to say. I speak to myself. I speak to my ancestors. I really like to gather rocks and grime. I like to have a chunk of that. To know that I used to be right here. To know that was actual.

You possibly can depart your secrets and techniques within the desert. No matter you give to the desert — once you come again, it’s going to be there. The vitality you introduced with you. The collections of reminiscences of every expertise. Each time I return to the desert, I take into consideration the final time I used to be there or the time earlier than that.

The desert simply retains happening and on and on, and there’s no barrier, there’s nothing stopping you. Zora was all the time speaking about horizons and I really like that concerning the desert. I typically must remind myself that there’s a lot life past what I can see, what my current is. The desert permits me to really feel small, however it additionally permits me to know that I’ve a goal. After I permit myself to really feel and see the vastness of the universe, I’m ready as an artist to reconnect with my goal.

After I’m within the desert, time is nonexistent. Or slightly, after I’m within the desert, I really feel linked to time in a means that I don’t get to expertise typically. After I’m in L.A., I really feel time all the time. And I’ve been actually working at having a extra collaborative relationship with, and a greater understanding of, time.

Time may not really feel the identical within the desert. However you see traces of it in all places. You witness the shadows that the solar casts; you see the slightest modifications in gentle — tweaks to dawn, sundown, noon. You assume: I can’t consider I get to witness this magnificence. I can’t consider I get to have a look at and be close to these mountains which have such a historical past. My final journey to Joshua Tree, the sundown was so divine that I didn’t need it to finish.

Within the vastness of the desert, the whole lot feels aligned. The whole lot feels proper within the cosmos and proper inside myself. The desert opens up a psychic house for me to be trustworthy about my deepest goals, to only daydream about issues that perhaps I don’t even assume are attainable. At that second, it seems like there are not any limitations. You possibly can think about something. There are not any distractions. It’s actually therapeutic for Black people to expertise a spot the place there are not any obstacles. It seems like nothing can cease you.

There are such a lot of alternative ways to fly within the desert. The way you select to fly is a dialog between you and air.

Sophia Nahli Allison is an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker and photographer. As a Black queer radical dreamer, she reimagines the archives by excavating hidden truths. A meditation of the spirit, her work conjures ancestral reminiscences to discover the intersection of fiction and nonfiction storytelling. She is a South Central L.A. native.

Extra tales from Picture

Lifestyle

The debate over “LatinX” and how words get adopted — or not

Word Wars: Wokeism and the Battle Over Language – John McWhorter

YouTube

Part 2 of the TED Radio Hour episode The History Behind Three Words

New terms — like LatinX — are often pushed by activists to promote a more equitable world. But linguist John McWhorter says trying to enforce new words to speed up social change tends to backfire.

About John McWhorter

John McWhorter is an associate professor in the Slavic Department at Columbia University. He is the host of the podcast Lexicon Valley and New York Times columnist.

McWhorter has written more than twenty books including The Power of Babel: A Natural History of Language, Words on the Move: Why English Won’t – and Can’t – Sit Still (Like, Literally) and Nine Nasty Words. He earned his B.A. from Rutgers, his M.A. from New York University, and his Ph.D. in linguistics from Stanford.

This segment of the TED Radio Hour was produced by James Delahoussaye and edited by Sanaz Meshkinpour. You can follow us on Facebook @TEDRadioHour and email us at TEDRadioHour@npr.org.

Web Resources

Related TED Bio: John McWhorter

Related TED Talk: 4 reasons to learn a new language

Related TED Talk: Txtng is killing language. JK!!!

Related NPR Links

Latinx Is A Term Many Still Can’t Embrace

Why the trope of the ‘outside agitator’ persists

Next U.S. census will have new boxes for ‘Middle Eastern or North African,’ ‘Latino’

Lifestyle

Modern death cafes are very much alive in L.A. Inside the radical movement

In a second-story room in Los Feliz’s Philosophical Research Society, about a dozen people sit in a circle. Many of them are here for the first time and not entirely sure what to expect. The sandwich board sign in the courtyard below offers only a cryptic hint: “Welcome! Death cafe meeting upstairs.”

As the group settles in on this Thursday afternoon in May, organizer Elizabeth Gill Lui lays out the only two directives: “have tea and cake, and talk about death.”

Lui, a 73-year-old artist who wears chunky jewelry and bold glasses, starts by reading a passage from the musician Nick Cave’s recent memoir. It’s about how, in the face of staggering grief, speaking and listening can be a form of healing — which is ultimately what Lui hopes will transpire over the next couple of hours, in this room decorated with patterned carpets and tall bookcases.

“The tradition in Southern California has long been about the journey. Making the most of the journey creatively, playfully, intellectually. That’s what I also like about the death cafe.”

— Elizabeth Lui, artist and organizer of a twice-monthly death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society

To initiate the exchange, she instructs the group to “go around in a circle and say what brought you to death cafe.” It’s a simple enough question, but one that elicits complex, deeply personal responses. Some attendees say they’ve come because they’re struggling with how to care for aging parents, or because they lost a loved one during the pandemic. Others have recently been through a life transition — a move back home, a college graduation, recovery from an illness. Or they’re wrestling with anxieties about their mortality. No matter the reason, everyone seems to be seeking some form of comfort, connection and community.

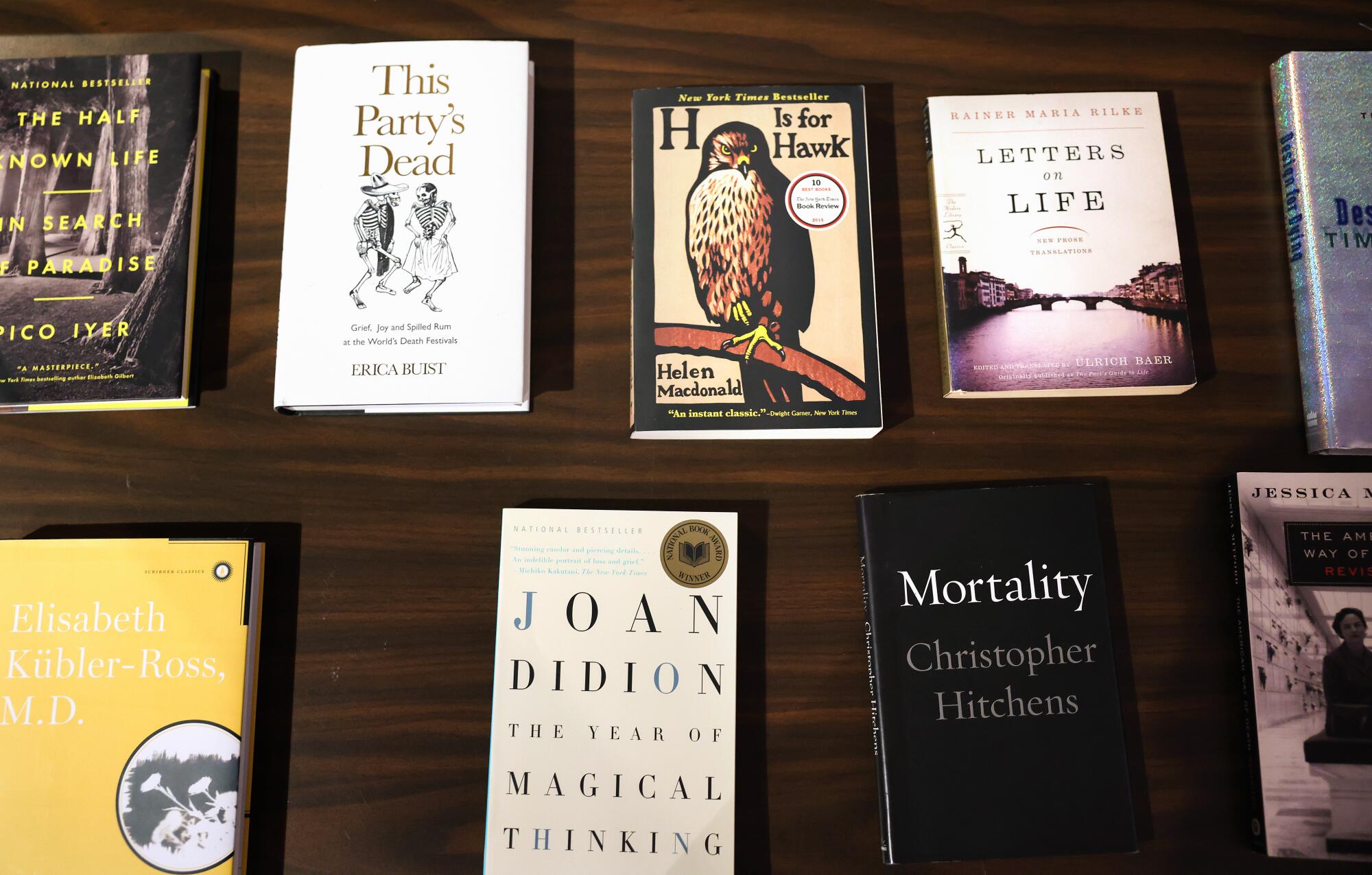

Reading material suggested by Elizabeth Lui, who hosted a death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society.

“The tradition in Southern California has long been about the journey. Making the most of the journey creatively, playfully, intellectually,” Lui tells me in the Philosophical Research Society’s regal library. “That’s what I also like about the death cafe. It has this edge of humor to it. If you’re at a dinner party and it’s boring, you can just say, ‘Have I told you about the death cafe I go to?’ and everybody just laughs. It’s such a great entree to the conversation.”

Lui’s twice-monthly gathering is one of several death cafes that have sprung up over the past two years in Los Angeles. Heavy Manners Library, an art space and lending library specializing in independent books and zines, holds one every other month. Its organizer, Emily Yacina, has made a habit of bringing donuts for the mostly 20- and-30-something tattooed crowd. Artist Ailene deVries held a death cafe in April at Gorky, an Eastside feminist collective that hosts workshops and pop-up events. North Figueroa Bookshop in Highland Park announced its first death cafe last summer, led by death doula Hazel Angell. A collaged flier for the meeting showed a skeleton hand clutching a butterfly above a succinct description written in gothic font: “A group discussion of death with no agenda, objectives or themes.”

The agenda-less ethos of the death cafe was developed in 2011 by Jon Underwood. The then 38-year-old Buddhist student and former government worker is widely credited for hosting the first modern death cafe at his home in East London. He was inspired to organize it after reading about Swiss “cafe mortels,” gatherings designed by the late sociologist Bernard Crettaz in 2004 to break the stigma around talking about death.

Underwood died unexpectedly in 2017 due to complications from leukemia, but the movement he kickstarted remains very much alive. A website maintained by Underwood’s mother and sister includes a how-to guide for those looking to start their own death cafe, and a directory that lists more than 18,000 death cafes around the world.

Greg Golden, 73, center, shares his experience beside fellow death cafe participants Danielle Tyas, 23, left, and Haley Twist, 32, right, at the Philosophical Research Society.

Megan Mooney, a clinical and medical social worker who serves as a volunteer spokesperson for Underwood’s umbrella organization, says she’s seen an increase in death cafe listings since 2020.

“COVID really made people have to face their own mortality,” she said in a Facebook message. “There was no escaping it …There was a huge demand for people wanting to talk about death for the first time.”

That was certainly true for Lui, who says the “pervasiveness of death” during the first couple years of the pandemic led her to get certified as an end-of-life doula in March 2022.

“I really was alarmed by the fact that we couldn’t form a consensus on how to deal with the pandemic and deal with the widespread phenomenon of this many deaths,” she said. “I don’t think the seriousness of it was something that we were even able to grasp because we avoid this topic at all costs.”

Though Lui’s death cafe may be the most frequently held one in Los Angeles, it’s not the county’s first. Hospice social worker Betsy Trapasso claims that distinction, after having launched a death cafe from her home in Topanga Canyon in 2013.

“It’s not a support group. It’s not a grief group,” Trapasso told The Times that year. “My whole thing is to get people talking about [death] so they’re not afraid when the time comes.”

During the event, Trapasso asked the group of aging professionals to inhale some lavender oil to relax at the start of the session. (Though she no longer hosts a death cafe, she maintains a Facebook page where she posts articles and events related to aging, grief and end-of-life care.)

Participants sit in a circle at the death cafe.

More than a decade later, there are no bongos or essential oils at L.A.’s latest wave of death cafes and, most noticeably, their attendees skew younger. At the Thursday and Saturday sessions I attended at the Philosophical Research Society, most people were in their 20s, 30s and early 40s. At Heavy Manners Library on a Tuesday night, the group would not have looked out of place at a music show at the Echoplex down the street.

Lui sees the attendance of the millennials and zoomers at her death cafes as evidence of an unfortunate reality: that younger generations are experiencing the loss of loved ones. Some of them have cited suicide, alcoholism and drug overdoses as the cause.

“Young people are being exposed to friends dying, and more often than I think people realize,” she said.

Yacina, who leads the death cafe at Heavy Manners Library, is one of them. The 28-year-old indie rock musician says a good friend of hers died during her sophomore year of college, and she found the experience isolating, profound and “identity-forming.” Then, in 2021, she mourned the death of yet another friend, whom she later wrote a song about. Yacina said she realized “there’s no escape to people dying, and in fact, it’s actually the one true thing that we all can count on.” It led her to wonder: “Why don’t we talk about it more?”

Upcoming L.A. death cafes

She organized the Echo Park death cafe in June 2022, just a few months before Lui started one in Los Feliz. Like Lui, Yacina had recently gotten certified as an end-of-life doula, and the pandemic had planted the idea of death more firmly in her consciousness. In a phone interview, she recalled worrying that she could lose her parents to COVID-19.

“It was such a scary feeling, but the truth is, you could lose anyone at any time,” she said.

It’s a truth that deVries, the 27-year-old artist who recently held a death cafe at Gorky and plans to hold another in Long Beach this summer, had to learn the hard way.

“When I was 18, my partner just suddenly passed in a very traumatic way, so I wasn’t really sure where to put the conversation,” she said. “I think the death cafe was the first time that I felt I had a container to express my interest.”

Reading material suggested by Elizabeth Lui.

Sara Alessandrini, 35, listens closely as another participant shares during the death cafe.

Not everyone who attends these events has experienced a death in their family or community. Some attendees instead see death as a potent metaphor for life’s big changes and all the grief that comes along with them.

“It also helped me with living life in the moment and letting go of certain things,” said Sara Alessandrini, a 35-year-old filmmaker who attends Lui’s death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society.

When it’s her turn to share her reason for coming to the Thursday afternoon group, Alessandrini announces to the group that she wants to reflect not on the death of a person, but of her childhood. She talks about boundaries and healing. It prompts others to chime in, openly sharing stories about their upbringings. When the conversation comes to a pause, Lui offers some warm advice to Alessandrini: “I think you need to protect yourself even better than you think you’re protecting yourself.”

Lui often takes on a maternal role in the group. During one of my visits, she asks for an attendee’s phone number so she can text them a message of support on a day they say they’re dreading. At a separate session, she gets up from her chair to console someone in emotional distress. After the meetings, she emails death-themed book and movie recommendations to newcomers, who often comprise the majority of attendees. Timothy Leary’s “Design for Dying,” the Oscar-winning Japanese drama “Departures,” and the Sundance-winning documentary “How to Die in Oregon,” are all on her list.

Since many of her attendees are artists themselves, she sends out invites to their events, which often intersect with ideas about death. Recent examples include an online radio program featuring songs for funerals and a solo show about grief debuting at the Hollywood Fringe festival this month.

Lui sometimes signs her emails: “Hope to see you when it fits.” She wants attendees to know there’s no obligation to return to her death cafe. Even still, the group can sometimes get large and unwieldy. At one recent death cafe, Lui recalled, there were 30 people, “and that was a little too much.”

Michael Allison, 62, laughs a little while sharing with the group of participants in the death cafe.

The death cafe can sometimes feel like group therapy. But Lui makes no claims of being a therapist. “I think in a good way, we’re not therapists,” she told me. “Because we’re not just nodding and listening and letting them figure out their own truth. We actually have some ideas about where you find meaning in your life.”

At the Thursday afternoon death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society, everyone has so much to say that the conversation stretches for hours. Toward the end, it becomes loose and playful, resembling a late-night heart-to-heart. Between bouts of tears and laughter, someone asks: Do you think you know that you’re dead after you’ve died? Another poses a question: Is it just me, or has anyone else ever wondered if your dead parent can see you when you’re having sex? The room giggles, and it reminds one attendee to share her own story about her deceased mother.

At some point, Lui asks whether anyone knows the time. It’s 6 p.m. — meaning the death cafe has stretched on for four hours, twice as long as scheduled. Lui frantically apologizes, but nobody seems to mind. They hang around, talking and eating cupcakes.

“Maybe we need a weekend retreat or something?” Lui suggests. But even a few days wouldn’t be enough to contain everyone’s questions about one of life’s greatest mysteries. For now, her cafe will have to suffice.

Lifestyle

'We Are Lady Parts' rocks with bracing honesty and nuance : Pop Culture Happy Hour

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewson, Dem leaders try to negotiate Prop 47 reform off California ballots, as GOP wants to let voters decide

-

News1 week ago

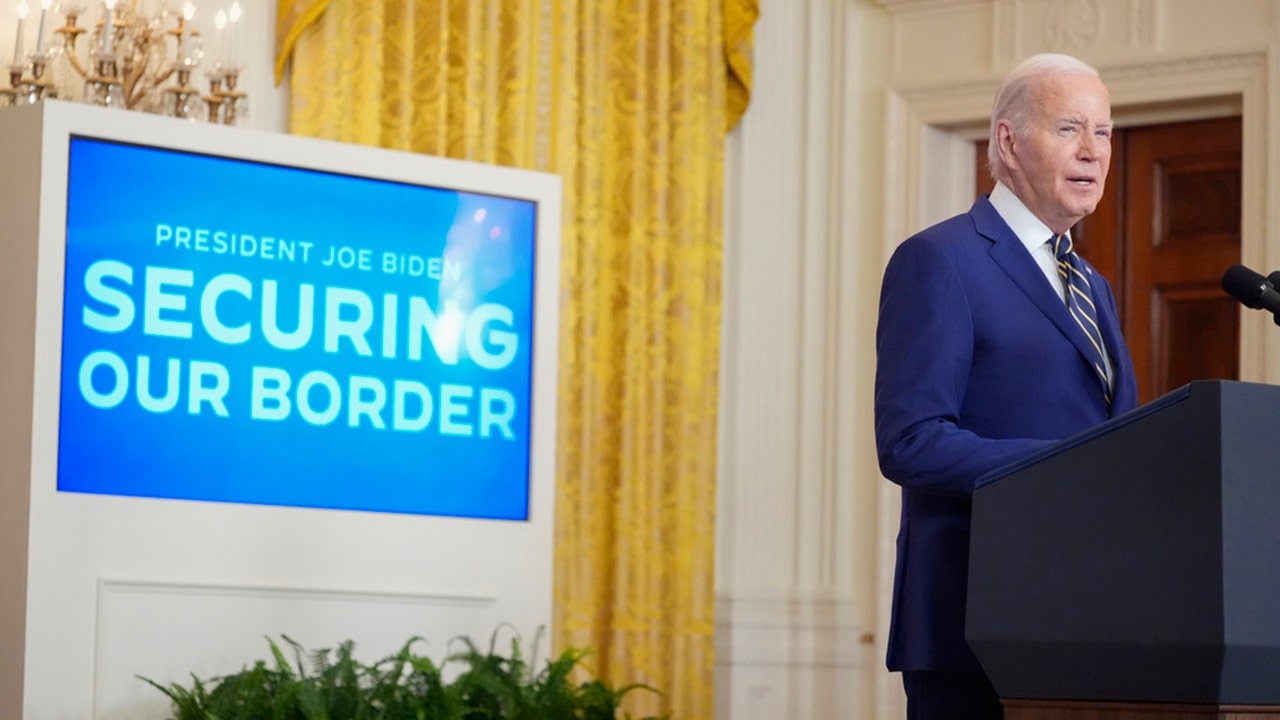

News1 week agoWould President Biden’s asylum restrictions work? It’s a short-term fix, analysts say

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoDozens killed near Sudan’s capital as UN warns of soaring displacement

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead Justice Clarence Thomas’s Financial Disclosures for 2023

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘Bloody policies’: Bodies of 11 refugees and migrants recovered off Libya

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoEmbattled Biden border order loaded with loopholes 'to drive a truck through': critics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoGun group vows to 'defend' Trump's concealed carry license after conviction

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoShould Trump have confidence in his lawyers? Legal experts weigh in