Lifestyle

‘Birds Are My Eyesight’

On an average morning, Susan Glass can sit on the patio at her condominium complex in Saratoga, Calif., and identify as many as 15 different bird species by ear: a stellar’s jay, an acorn woodpecker, an oak titmouse.

For her, birding is more than a hobby. “Birds are my eyesight,” said Ms. Glass, a poet and a professor of English at West Valley Community College who has been blind since birth. “When I check into a hotel in Pittsburgh, I might remember the rock dove and the house finch in the parking lot, rather than the architecture.”

When the audio is played, captions appear that read “Drink your tea! Drink your tea! Drink your tea!”

Mnemonics are used by many birders to help identify bird calls. Some are more clear than others. The eastern towhee sounds like it’s saying “Drink yer teeeeea!” Audio via Michael Hurben

Ms. Glass, 67, was a child when she first noticed the birds twittering outside her family’s home on the Lake Erie coast of Michigan. “My mother told me they were a swallow called the purple martin,” she said. “I was paying attention to where they were flying, and I could actually start to hear the dimensions of our little cabin, the screen porch, the front yard.”

She has mapped her surroundings by bird song ever since.

Birding got a significant boost with the pandemic: With so many people doing less, they tuned in to the sounds of nature more; and with lockdowns came a reduction in noise pollution, which made the bird calls all the more pronounced.

Sarah Courchesne, a Massachusetts Audubon program ornithologist in Newburyport, attributes the increased interest in birding partly to the fact that it’s a way for people of all abilities to tap into nature — whether by eye, by ear or both.

As the birding community grows larger and more diverse, Ms. Courchesne said, birding clubs and conservation organizations are thinking more about accessibility, and this is changing the way they talk about birding and think about it.

For one thing, the terminology is evolving. According to Freya McGregor, a 35-year-old birder and occupational therapist specializing in blindness and low vision, the term “birder” was once reserved for those who were more serious than the hobbyist “bird watcher.” But increasingly, “birder” is becoming a catchall, thanks to a growing awareness that some hobbyists identify birds not by watching, but exclusively by listening.

Susan Glass, a poet and professor who has been blind since birth, has been mapping her surroundings by birdsong since childhood.

Jim Wilson/The New York Times

She sometimes uses a Braille Sense computer – or her phone – to record audio from birding trips.

Jim Wilson/The New York Times

Spaces are evolving too. Nature trails from Cape Cod to the Colombian Andes are being reimagined, with features like wheelchair-accessible terrain and guardrails to guide guests with low vision. The Audubon Society in Massachusetts recently introduced a series of All Person’s Trails, which are designed for accessibility.

Public programming is also expanding. Birding organizations across the country are introducing a new kind of bird “walk” — one called a “big sit,” where you just stay put. These stationary birding events, popularized by the New Haven Birding Club in the early 1990s, is a type of competitive event, sometimes hosted as a fund-raiser, in which teams of birders stay within their own 17-foot-diameter circles for a 24-hour period and identify as many birds as possible.

When the audio is played, captions appear that read “Cheer up, cheerily! Cheer up, cheerily”

Early ornithologists attempted to describe the rhythmic phrases of the American robin’s cheerful song with words like “Cheer up, cheerily.” Audio via Jerry Berrier

In May, Ms. Courchesne hosted a big sit alongside Jerry Berrier, a blind birder, on an All Person’s Trail near Ipswich, Mass. Mr. Berrier, who lives in Malden, Mass., said he wanted his event to be less competitive and more meditative than a traditional bird sit.

While some studies have shown that simply hearing bird song may alleviate anxiety and boost feelings of well-being, Mr. Berrier, 70, said the benefits go beyond that for him. “Birding gives me a connection with a world I can’t see,” he said, including when the world outside is waking up in the morning and winding down at dusk.

Jerry Berrier often goes into his backyard in Malden, Mass., with his parabolic microphone to listen to birds.

Kayana Szymczak for The New York Times

A microphone is situated underneath a bush outside of Mr. Berrier’s home.

Kayana Szymczak for The New York Times

He doesn’t even need to step outside to listen. Mr. Berrier’s home is surrounded by an audio mixer and sound recording equipment — parabolic microphones and devices he has custom-made — piping in bird sounds from the outdoors in real time, and recording bird song in quieter environments.

At the Ipswich bird sit, Mr. Berrier pointed people to the resonant song of an ovenbird; the buzzy trills of various warblers and the flutelike notes of a Baltimore oriole, which sometimes sounds like it’s saying: “Here; here; come right here, dear.”

When teaching newcomers how to distinguish birds by ear, Mr. Berrier often shares mnemonics. For the eastern towhee, he said, listen for a bird that tweets: “Drink yer teeeeea.” The American robin sounds like it’s singing, “Cheer up, cheerily.” The Northern cardinal might be saying, ‘Watch here, watch here.’” American goldfinches call “potato chip” in flight, while olive-sided flycatchers chirp, “Quick! Three beers!”

When the audio is played, captions appear that read “Here! Come right here! Here! Come right here, dear. Come right here!”

One of the mnemonic phrases that Mr. Berrier and other birders use to identify the the Baltimore oriole is “Here; here; come right here, dear.” Audio via Jerry Berrier

Mr. Berrier has been birding since the 1970s, when he was in college at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania. There, a professor gave him a special assignment to replace the dissection-based portion of his biology course.

“He ended up giving me probably one of the greatest gifts that’s ever been given to me by recommending that I listen to his record albums from Cornell University that had bird sounds on them,” Mr. Berrier said. “He said, ‘I want you to listen to these during the semester, and at the end, your lab portion of the grade is going to be based on a walk in the woods with me, and I will ask you to identify some of the sounds you hear.’”

At first, Mr. Berrier found it daunting to distinguish bird species in the wild just by their sounds. “I just thought, ‘Man, these birds all sound the same,’” he said. “But by the end of the semester, I was hooked, and I’ve been doing it ever since.”

During these early outings, Mr. Berrier identified cardinals, with their laserlike trills; robins with their cheery twittering; and red-winged blackbirds, whose call he still thinks of as “a harbinger of spring.”

When the audio is played, captions appear that read “Watch here! Watch here! Cheer, watch here! Cheer! Pretty, pretty, pretty, pretty.”

To some, the Northern cardinal sounds like it’s saying “pretty, pretty, pretty.” Audubon Vermont compares its call to a Star Wars light saber. Audio via Jerry Berrier

‘A Bird Heard’

For birders looking to build out their “life list” of every bird they’ve ever spotted, knowing these calls can be indispensable: The American Birding Association’s rules for identifying a bird species make no qualitative distinction between “a bird heard” and “a bird seen.”

Trevor Attenberg, a scientist and writer who is blind and lives in Portland, Ore., pointed out there are plenty of birds you have far less chance of seeing than hearing. “Something like 60 to 70 percent of the birds that you will encounter, you will only be able to encounter by ear,” Mr. Attenberg said.

“I’m always listening to what kind of birds I can hear in any given environment, whenever I step outside, and it tells me so much,” he said. “It tells me about the weather, and the seasons. It tells me about this specific landscape that I’m in. Even when I’m in urban environments, it can tell me about the quality of habitat.”

When the audio is played, captions appear that read “whip-poor-will whip-poor-will”

The Mexican whip-poor-will, which can be found in the southwestern U.S., has a call that sounds like its name. Audio via Michael Hurben

Learning the percentage of birds that one might only ever have a chance to identify by ear gave Mr. Attenberg, 40, more confidence. “It’s indicating to me — as the blind birder, uncertain as to my place in science — that I actually can compete with other ornithologists that can spot birds through binoculars and so forth, which I can’t really do,” he said. “Learning that, in fact, such a large share of possible bird detections are only going to come through the ear, tells me that, well, there is room for blind people — and people that just enjoy using their ears for listening or collecting information — to learn about birds in this way.”

But the notion of “a bird heard” is becoming increasingly imperiled as noise pollution brings about fundamental changes in the way nature sounds. Ornithologists have reported birds changing the tenor of their calls as they strain to be audible over the din of human-made noise — whether it’s crypto mining or just the everyday sounds of leaf blowers or car traffic.

When the audio is played, captions appear that repeat “Who cooks for you, who cooks for you?”

The barred owl seems to be asking, “Who cooks for you?” Audio via Michael Hurben

Ms. Glass, the poet in California, said she has noticed that, over time, there are fewer bird sounds altogether. “There is no longer, in my part of the world, what you would call a dawn chorus — an overwhelming bird chorus that drowns out everything else,” she said. Bird song ebbs and flows with the seasons, peaking during migrations. But studies indicate that as bird populations decline, bird song is declining, too.

Jerry Berrier often stands on his deck with his shotgun mic near sunset, and records bird sounds, which he later edits.

Kayana Szymczak for The New York Times

5,400 Birds

Michael Hurben, 56, is on a mission to document what he can, while he can. Because of a degenerative retina disease, his field of view has narrowed over time, from 180 degrees to, he estimates, less than one-tenth of that.

So Mr. Hurben, a retired engineer who lives in Bloomington, Minn., has doubled down on his love of birding, and is well on his way to identifying 5,400 different birds — a little more than half of all bird species in the world. “I just want to be able to say that I’ve identified the majority,” he said.

He and his wife, Claire Strohmeyer, who is also 56 and a clinical researcher, have visited dozens of international destinations to check rare species off the list. But a narrow scope makes searching for a bird in a tree, or spotting it through binoculars, especially challenging.

This makes his ability to identify birds by ear indispensable. He has brushed up on his skills online, but also by birding with other birders by ear, including Mr. Berrier, who joined Mr. Hurben on a birding trip to Cape May, N.J., last year.

Mr. Hurben finds it increasingly difficult to hear certain bird song, like the very high-pitched calls of the colorful cedar waxwing.

“Before we go on a trip, I will try to really study the calls ahead of time,” he said. While some calls do require a mnemonic to remember, others are very distinctive.

When the audio is played, no mnemonic captions appear

The screaming piha has a call so unique it’s a go-to for sound designers when making films set in jungles, said Michael Hurben, a birder. He recorded this sound clip on a birding trip to Brazil. Audio via Michael Hurben

He cited for example, the screaming piha, a plain-looking gray bird he and his wife trekked into the Amazon to identify. Its unique call is a go-to for sound designers when making films set in jungles, he said. (Listen for it in Werner Herzog’s 1972 film, “Aguirre, Wrath of God.”) Likewise, another South American bird, the sharpbill, has a call that sounds “like a falling bomb,” Mr. Hurben said. “I hear that song once, and I’ll never forget it the rest of my life.”

Lifestyle

The Eurovision Song Contest kicked off with pop and protests

Baby Lasagna of Croatia performs the song Rim Tim Tagi Dim during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Martin Meissner/AP

Baby Lasagna of Croatia performs the song Rim Tim Tagi Dim during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

MALMO, Sweden — Competition in the 68th Eurovision Song Contest kicked off Tuesday in Sweden, with the war in Gaza casting a shadow over the sequin-spangled pop extravaganza.

Performers representing countries across Europe and beyond took the stage in the first of two semifinals in the Swedish city of Malmo. It and a second semifinal on Thursday will winnow a field of 37 nations to 26 who will compete in Saturday’s final against a backdrop of both parties and protests.

Baby Lasagna of Croatia performs the song Rim Tim Tagi Dim during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Martin Meissner/AP

Baby Lasagna of Croatia performs the song Rim Tim Tagi Dim during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

Ten of the 15 acts performing Tuesday were voted through to the final by viewers. They include Croatian singer-songwriter Baby Lasagna, whose infectious electro number “Rim Tim Tagi Dim” is the current favorite to win, and Ukrainian duo alyona alyona and Jerry Heil, flying the flag for their war-battered nation with the anthemic “Teresa & Maria.”

Also making the cut were goth-style Irish singer Bambie Thug, 1990s-loving Finnish prankster Windows95man and Portuguese crooner Iolanda. Iceland, Azerbaijan, Poland, Moldova and Australia were eliminated.

Other bookmakers’ favorites who will perform Thursday include nonbinary Swiss singer Nemo, Italian TikTok star Angelina Mango and the Netherlands’ Joost Klein with his playful pop-rap song “Europapa.”

Bambie Thug of Ireland performs the song Doomsday Blue during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Martin Meissner/AP

Bambie Thug of Ireland performs the song Doomsday Blue during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

Anti-war demonstrations become the backdrop

Security is tight in the Swedish city, which expects an influx of some 100,000 Eurovision fans, along with tens of thousands of pro-Palestinian protesters. Israel is a Eurovision participant, and demonstrations are planned on Thursday and Saturday against the Israel-Hamas war, which has left almost 35,000 Palestinians dead.

Israel’s government warned its citizens of a “tangible concern” Israelis could be targeted for attack in Malmo during the contest.

Organizers told Israel to change the lyrics of its entry, originally titled “October Rain” in apparent reference to Hamas’ cross-border Oct. 7 attack that killed some 1,200 Israelis and triggered the war. The song was renamed “Hurricane” and Israeli singer Eden Golan was allowed to remain in the contest.

Jean Philip De Tender, deputy director-general of Eurovision organizer the European Broadcasting Union, told Sky News that banning Israel “would have been a political decision, and as such (one) which we cannot take.”

Police from across Sweden have been drafted in for Eurovision week, along with reinforcements from neighboring Denmark and Norway.

Sweden’s official terrorism threat level remains “high,” the second-highest rung on a five-point scale, after a string of public desecrations of the Quran last year sparked angry demonstrations across Muslim countries and threats from militant groups. The desecrations were not related to the music event.

Eurovision’s motto is “United by Music,” but national rifts and political divisions often cloud the contest despite organizers’ efforts to keep politics out.

Flags and signs are banned, apart from participants’ national flags and the rainbow pride flag. That means Palestinian flags will be barred inside the Malmo Arena contest venue.

Some musicians seem determined to make a point. Eric Saade, a former Swedish Eurovision contestant who performed as part of Tuesday’s show, had a keffiyeh, a headscarf associated with the Palestinian cause, tied around his wrist as he sang.

Afterwards, organizers said in a statement that “we regret that Eric Saade chose to compromise the non-political nature of the event.”

Performers are feeling political pressure, with some saying they have been inundated with messages on social media urging them to boycott the event.

“I am being accused, if I don’t boycott Eurovision, of being an accomplice to genocide in Gaza,” Germany’s contestant, Isaak, said in an interview published by broadcaster ZDF. He said he did not agree.

“We are meeting up to make music, and when we start shutting people out categorically, there will be fewer and fewer of us,” he said. “At some point there won’t be an event anymore.”

ISAAK of Germany performs the song Always on the Run during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Martin Meissner/AP

ISAAK of Germany performs the song Always on the Run during the first semi-final at the Eurovision Song Contest in Malmo, Sweden, on Tuesday.

Martin Meissner/AP

One person who knows how Eurovision unity can collide with bitter reality is singer Manizha Sangin, who represented Russia at the contest in 2021. The country was expelled the following year over its invasion of Ukraine.

Manizha, who performs under her first name, spoke out against the war. As a result, her performances were canceled in Russia and her music banned from public spaces. The singer remains in Russia but has found it all but impossible to work.

“People are afraid to work with me here because they’re afraid to have consequences after, problems after that,” she said.

Despite the difficulties, Manizha has recorded a single, “Candlelight,” which she is releasing on Wednesday as “a message of hope.”

“Music cannot stop war,” she said. But “what music can do is inspire people.”

Manizha thinks Russia will one day return to the Eurovision fold – but not soon.

“Maybe next generation,” she said. “But for now, relationships are too complicated. And then that makes me sad, you know, because that’s why people are not hearing each other. Because we are separated from each other. And the thing, is music should unite.”

Lifestyle

Weed changed this California town. Now artsy residents are all in on psychedelics

On a brisk mid-March night in the small Northern California town of Grass Valley, more than 100 people crowded around a Grateful Dead cover band in a drafty warehouse. They were an eccentric mix: aging hippies, hypebeast college kids and burners bundled in faux fur rainbow coats, swaying to guitar riffs. In the parking lot, people exchanged cigarettes, joints, pills and powders.

Scenes from a night at the Chambers Project, an art gallery curated by Brian Chambers in Grass Valley, California.

(Colin M. Day)

This is a typical night at the warehouse — home to an art gallery called the Chambers Project and a new nonprofit, Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust (PACT). It sits just off State Route 49 and shares its parking lot with a natural foods store. From the road, it can be identified only from its logo: an illuminati eye nestled into a pyramid, which sheds a tear into a river that vanishes into the horizon. The image was drawn by one of the most famous psychedelic artists, Rick Griffin, who created seven album covers for the Grateful Dead.

The logo was a taste of what awaited inside. Almost every corner of the warehouse was covered in trippy art. From the ceiling hung a twisted glass chandelier by Eric Dunn, its spiked lampshades mimicking the tendrils of a brain’s dendrites. On the walls were dozens of otherworldly paintings by Mario Martinez (a.k.a. MARS-1), who renders amorphous architecture straight out of science fiction. Behind the musicians, sculptures of bright pink disembodied legs and a matching pink unicorn in medieval armor add trippy ambience. Outside, projected onto the facade, was a kaleidoscopic video that overlaid cartoonish eyes, lightning bolts and sacred geometry.

Brian Chambers, founder and curator of the gallery, is the face of this event. The concert was part of the opening reception for his gallery’s new exhibition, “The Godfathers” — which showcases four artists who defined the art movement — and also the launch party for PACT, which he hopes will be a a community hub for the psychedelic-curious, whether that pertains to art, experimenting with substances, or educational programming about the two.

A recent PACT event included a benefit concert to raise money for a local marijuana farmer known as Uncle Jay, who’s battling cancer. This month, an exhibition of peyote paintings will donate proceeds to the Wixárika tribe of northwestern Mexico, California, Arizona and Texas — Indigenous people whose shamans famously guide people through spiritual peyote ceremonies.

They are also planning talks about major moments within psychedelic art history, a deep dive of blotter art, and a panel on magic mushrooms and their scientific properties.

“We have a community of care,” said Marci Hovanski, 48, who works at the natural foods store next door. “Brian’s bringing something so special, and it really just raises the whole frequency of the neighborhood.”

Mary Barry, 74, and her husband Jesus Ceballos, 72, have been attending Chambers’ art openings for years. Like many residents in Nevada County, where the biggest cash crop is marijuana, they moved to the quiet town 51 years ago to work on a friend’s weed farm and never left.

Ceballos wears a tangle of walrus beads over his tie-dye Grateful Dead T-shirt. He and Barry came tonight because they wanted to see the artwork and hear the Grateful Dead cover band. They’ve seen the original group play at least 50 shows, often timing the moment they dropped acid so they peaked at the song “Greensleeves.”

“If you’ve ever done psychedelics you feel comfortable in this environment. People recognize each other and they feel safe.”

— Marci Hovanski, Chambers Project patron

Grateful Dead shows were places for them to experiment with drugs, and Ceballos compares the Chambers Project to that environment. “The vibe here is very, very good,” he said.

In this way, Chambers’ nonprofit functions as a third space for the local community, especially those who dabble in psychedelics — substances like psilocybin (magic mushrooms), peyote, ayahuasca, DMT, LSD, ketamine and MDMA — that affect the mind and often cause hallucinations. Whether someone’s smoking weed to make art-viewing more pleasurable, dropping acid to enhance a concert experience, or dosing magic mushrooms to go on a path of self-discovery, Hovanski said the Chambers Project provides a nonjudgmental setting to do that.

“If you’ve ever done psychedelics, you feel comfortable in this environment,” Hovanski said. “People recognize each other and they feel safe.”

Even so, she said visiting the gallery is thrilling while sober too. “People can just go there and be themselves. It’s kind of magic. … It’s opened up a space that holds the rainbow. It’s like the end of the rainbow.”

The Chambers Project warehouse sits just off State Route 49 and is home to an art gallery and a new nonprofit, Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust (PACT).

(Colin M. Day)

Life after weed farms

After California legalized recreational marijuana in 2016, Grass Valley’s economy entered a recession. Many independent farmers couldn’t meet the regulation requirements for legal operation and shut down. Psychedelic culture, however, might be the ticket to Grass Valley’s recovery; through Chambers’ magnetism, more artists have been taking trips to this rural town on the Yuba River.

“Tourism is like the only thing we’ve got going,” Hovanski said. “Brian opened a light, a place for people to see love or care. That just opens the space for more creativity, more greatness.”

Before trekking to Grass Valley, I first met Chambers over Zoom in February. The 44-year-old gallerist has a long, gray beard. The day we spoke he wore a baseball cap embroidered with the illuminati eye from the Chambers Project logo. In the background was a large, red swirling canvas by MARS-1, a young artist whom Chambers has mentored. Positioned behind Chambers, it made him glow like a martian.

“This is a moment that I’ve been anticipating and waiting for,” he said.

He was referring to a cultural shift surrounding psychedelics. Many cities across the nation have decriminalized possession and in Oregon and Colorado, voters passed ballots that allowed for state-regulated psilocybin medical centers. Oregon opened its first psilocybin clinic in 2023, and so-called healing centers are slated to arrive in Colorado in 2025.

“This is a moment that I’ve been anticipating and waiting for.”

— Brian Chambers, founder of the Chambers Project and the nonprofit Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust (PACT)

In the meantime, cities are advocating for psychedelics use on the local level. In the last five years, possession of magic mushrooms has been decriminalized to varying degrees in cities across California, including Oakland, Santa Cruz, Arcata, San Francisco, Berkeley and Eureka.

Last October, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a state-wide bill that would have decriminalized various psychedelics. Legislators, in step with public opinion, have nevertheless continued their push to grant wider access to the substances. State Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) introduced a plan in February that would legalize psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

Beyond the medical industry, psychedelic aesthetics are jumping from counterculture into the mainstream: There are now black light-lit bars that specialize in kava, a root plant that can produce low-level psychoactive effects; immersive art chains like Meow Wolf, which sells chromadepth glasses that mimic a trip by producing prismatic halos around lights; and even a brand new shroom festival in Denver, which will have mushroom grow kits for sale.

Artwork featured at the Chambers Project’s “Godfathers” exhibition.

(Colin M. Day)

A looming shift

Due to recent studies, including an FDA-backed statement that “psychedelic drugs show initial promise as potential treatments for mood, anxiety and substance use disorders,” the substances may be on the precipice of legalization in California and across the United States.

“Psychedelics are remarkable for their potential to elicit non-ordinary states of consciousness and ability to facilitate healing through experiences of profound transpersonal and mystical states,” said Barbara Chandler, a therapist and ketamine-assisted psychotherapist based in Truckee.

“These experiences can expand one’s sense of self and deepen one’s understanding of existence and connectedness,” she said.

Chambers sees the timing of PACT’s launch as a chance to take advantage of this shift. He wants the organization to be a resource for the new generation of people discovering these substances.

“People that are exploring it and getting into that side of life are doing it with an intention,” Chambers said. “They’re trying to use them as tools to get through it. I see enormous value in that, and I think it’s a beautiful thing.”

Chambers is alluding to the fact that recent research has shown that psychedelic-assisted therapy — when drugs are combined with psychotherapy or talk-therapy — can treat PTSD, depression and chronic pain. It’s possible this has helped destigmatize the drugs. A recent poll out of UC Berkeley shows that 61% of registered voters across America support regulated use of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

Currently the federal government classifies all psychedelics as Schedule I controlled substances, meaning they have “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” But there are signs the FDA is getting closer to downgrading that status for psilocybin, LSD and MDMA. Compass Pathways and the Multidisciplinary Assn. for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) are among organizations that have entered phase III clinical trials with psilocybin and MDMA therapies. Experts say that’s the final hoop to clear before federal agencies acknowledge a drug’s medical potential and clear it for FDA-approved programs.

In June 2023, the FDA issued its first draft guidance for conducting psychedelic research. That will help scientists design studies that can lead to the drugs being approved for the market.

“The move by the FDA has researchers, advocates for veterans and others hopeful for the development of better medication for frequently diagnosed disorders,” Eric Licas reported for The Times in 2023.

Medical providers have already used legal loopholes to get certain illegal substances to patients. Ketamine, for example, is FDA-approved for anesthetic use, which allows clinics to obtain it. They can then turn around and administer it off-label, meaning they can use it for an unapproved treatment, which is legal so long as “it is based in sound medical evidence.” This workaround has helped roughly 500 to 750 ketamine clinics pop up around the country since 2020.

Artwork featured at the Chambers Project’s “Godfathers” exhibition.

(Colin M. Day)

Reaching a new generation

As a longtime user of psychedelic substances, Chambers sees legalization as the new gateway into his culture. He discovered psychedelic drugs in 1995 during his sophomore year of high school, when he said he showed up to his science class on LSD and became enthralled with an Alex Grey poster that hung in the classroom.

Beyond its mental effects, he was immediately drawn to the aesthetics — swirling colors, optical illusions and surreal depictions of cognition — associated with it. At age 15, he purchased his first piece of art, a “Bicycle Day” poster celebrating the discovery of LSD signed by the chemist who made it. Chambers, who said he earned a comfortable living in the marijuana industry, owns roughly 400 works of psychedelic art.

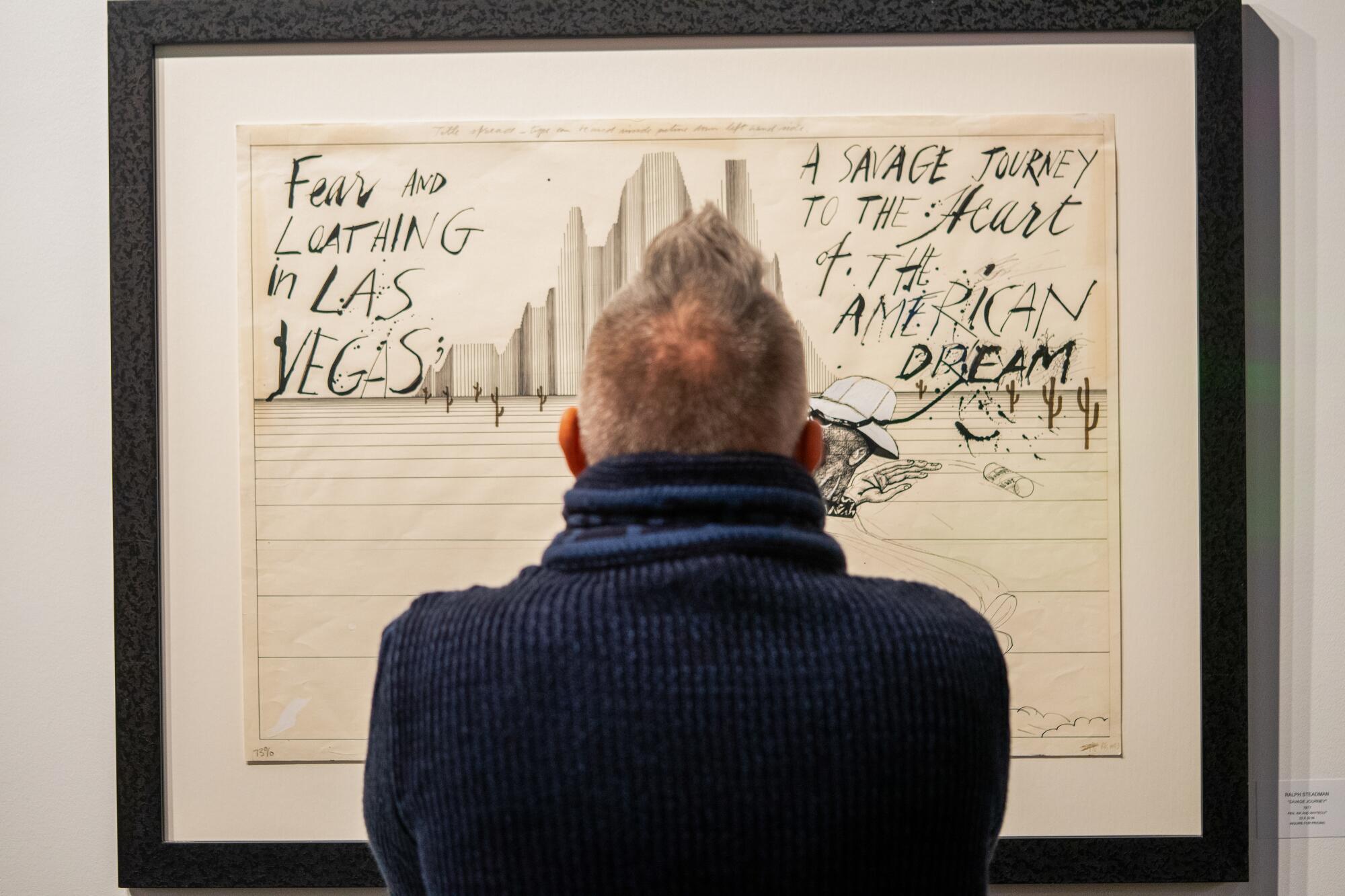

That candy-colored trove now rotates through the Chambers Project. The current “Godfathers” show (running until May 25) includes original pen-and-ink drawings that Ralph Steadman drew for Hunter S. Thompson’s seminal work of gonzo journalism, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas”; Rick Griffin’s “flying eyeball,” which cemented itself into history when it appeared on a Jimi Hendrix Experience concert poster in 1968; the pop surrealist Roger Dean’s “Relayer,” a serpentine painting that became an album cover for the prog-rock band Yes; and ephemera from a gritty Manhattan venue called Psychic Solutions Gallery, founded by Jacaeber Kastor, that treated blotter papers as high art.

Brian Chambers, left; Jacaeber Kastor, right. Kastor is one of the artists in the exhibition and founded Psychedelic Solution Gallery, a gritty Manhattan venue that treated blotter papers as high art.

(Colin M. Day)

Since psychedelics have become less taboo, the interest in Chambers’ art collection has grown. He said he has sold work to the Pritzker family, which has placed a number of his pieces at its Grand Hyatt Hotel in San Francisco. Often deemed lowbrow, unserious and too commercial, a wider acceptance of magic mushrooms and ketamine among some pockets of the country also means that the art is no longer reserved for outcasts and hippies.

“We’re trying to make these world-class, globally known artists accessible to the common folk that don’t come from money or a serious art background,” Chambers said.

He supports artists like MARS-1, Damon Soule and Justin Lovato by providing them studio space, showing their work and selling it to his network of collectors. Chambers has also encouraged many of these artists to relocate to Grass Valley to be closer to the community he’s building.

Chambers met Soule, a 49-year-old artist known for drawing flowing grids as optical illusions, in 2009 in San Francisco. Five years later he made the move to the woods. Soule chatted with me over Zoom from his homemade art studio in April, where he relied on one bar of spotty cell service. Pixelated, he sat in front of plywood walls covered with black-and-white painting studies, an artsy recluse in his off-grid sanctuary.

“Artists tend to be individualistic and focused on their own little world,” he said. “Brian is a connection-maker. It’s good to be near someone who helps you meet other artists, other musicians, people who have parties and collaborative events.”

Scenes from a night at the Chambers Project, an art gallery curated by Brian Chambers.

(Bailey Whitehill)

Soule calls PACT “the clubhouse” because it’s always filled with a diverse set of creative people united by the profound experiences they had taking psychedelics.

When I spoke to Chambers, he was careful to clarify that, though he is a passionate advocate of psychedelics, PACT is not a medical organization, nor does it distribute substances. Instead, they focus on education by holding discussions with experts, historians and artists who help people understand how to safely consume drugs if they so desire.

Gagan Levy, a PACT board member and founder of We Are Guru, a creative agency that plays a large role in pushing for the legalization of psilocybin, believes PACT’s discussions are crucial for building a positive relationship with the drugs. He emphasizes the importance of “set and setting.” The phrase was coined by his mentor Ram Dass, the famed Harvard scientist and spiritual icon who conducted groundbreaking studies on psychedelics in the 1960s and wrote “Be Here Now.”

“We don’t have a Hunter S. Thompson, or ‘Fear and Loathing’ like that. We’re trying to recapture that, but in a totally new and weird way.”

— Woody Tuttle, Chambers Project patron

“What’s your mindset and the setting going into a psychedelic experience?” he asked. “Then, how do you have a mind-expanding experience, but, most importantly, how do you then integrate that into your life to be more fulfilled?”

Woody Tuttle, 21, traveled from Chico to attend the “Godfathers” opening. He said that because his generation lacks a true counterculture movement, his cohort sees psychedelics as more spiritual gateways to connecting with art, nature and other people. He said many of his peers are pairing their experiences with chants, intention-setting, spells and manifestation.

“We don’t have a Hunter S. Thompson, or ‘Fear and Loathing’ like that,” Tuttle said. “We’re trying to recapture that, but in a totally new and weird way.”

A Chambers Project visitor views artwork by “Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas” artist Ralph Steadman.

(Colin M. Day)

PACT cultivates an environment where people can discuss how psychedelics have provided them breakthroughs, healing and answers to personal questions.

“Integrating the psychedelic experience is as important as the experience itself,” the artist Soule said. “For me, art is the most direct way of transmuting all types of metaphysical spaces into the default world. It resonates with people by giving them a reflection of those shared places, states, mysteries.”

In Grass Valley, the community has embraced PACT and the Chambers Project. Their parties regularly sell out, the gallery has made the front page of the local newspaper more than once, and the Nevada County Arts Council has arranged private gallery tours for visitors.

By fostering a community around art, music and education, PACT hopes to transform this small, rural town into a preeminent hub for psychedelic culture.

“The art speaks for itself and it has really inspired a movement,” Chambers said.

Renée Reizman is an interdisciplinary writer, artist and educator based in Los Angeles. She researches the ways infrastructure impacts culture, community and environment. Find her work at @reneereizman.

Lifestyle

Pioneering stuntwoman Jeannie Epper, of 'Wonder Woman' and 'Charlie's Angels' dies

Jeannie Epper accepting a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Taurus World Stunt Awards in 2007.

M. Phillips/WireImage/Getty

hide caption

toggle caption

M. Phillips/WireImage/Getty

Jeannie Epper accepting a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Taurus World Stunt Awards in 2007.

M. Phillips/WireImage/Getty

In the 1970’s, when Wonder Woman, the Bionic Woman or one of Charlie’s Angels outran villains, crashed through windows, and leaped over obstacles, viewers were really watching Jeannie Epper, dressed up as a superhero. The groundbreaking Hollywood stuntwoman’s career lasted more 70 years, across more than 150 films and TV shows. Epper passed away of natural causes at her home in Simi Valley, California on Sunday. She was 83 years old.

“As stuntwomen, we all descend from this lineage of stuntwomen such as Jeannie,” says Katie Rowe, president of the Stuntwomen’s Association of Motion Pictures, which Epper co-founded in 1967. “Back in the day, men used to do all the stunts — and they’d throw wigs on them, and dresses. But of course…they don’t move like women. So the women decided to get in on this whole racket. And here we are today.”

Epper began her career at age nine, in the 1951 film Elopement. After her parents sent her to Swiss finishing school, she returned to Hollywood for bit parts in the John Ford movie Cheyenne Autumn and the TV show The Big Valley. But in the late 1970’s, she found more opportunities, when women were given more action-oriented roles. She doubled for Lindsay Wagner on TV’s Bionic Woman, and for Kate Jackson on the TV series Charlie’s Angels. Her breakthrough role was as Lynda Carter’s main stunt double on the TV show Wonder Woman.

“She was always there on this set with me, whenever I had a stunt day,” Carter told NPR. “She did all the hard stuff. She set the standard for everyone else. She was the ultimate professional.”

I have a lot to say about Jeannie Epper. Most of all, I loved her. I always felt that we understood and appreciated one another.

After all, it was the 70s. We were united in the way that women had to be in order to thrive in a man’s world, through mutual respect, intellect and… pic.twitter.com/ghxY2JT5UP

— Lynda Carter (@RealLyndaCarter) May 6, 2024

Carter says the production initially cast a stunt man as her double. “They put a guy with a hairy chest in a Wonder Woman costume — a man with a square, chunky body,” she recalls. “You couldn’t get the camera far enough to know that it wasn’t a woman’s body with zero curves, just hairy arms and hairy armpits, and it just wasn’t gonna work.” Carter says they brought in Jeannie Epper, “and it was perfect.”

Carter says her double was an expert at horseback riding, and for other stunts, Epper trained or helped find other stuntwomen to do high falls, ride motorcycles, perform martial arts or do whatever was necessary for the scene. Back then, she says, the stunts were practical, without post-production effects such as CGI or A.I.

Entertainment Weekly once called Epper “the greatest stuntwoman who ever lived.” She came from a family dynasty of stunt performers. In fact, according to The Hollywood Reporter, director Steven Spielberg called them “Flying Wallendas of film,” comparing them to the famous circus family. Her father John Epper had been a stunt double for actors Gary Cooper, Errol Flynn and Ronald Reagan. Her sisters and brothers, Tony, Margo, Gary, Andy and Stephanie also worked in stunts. Her children and grandchildren have continued in her footsteps.

Epper had a long list of credits; She did cat fights on the soap opera Dynasty and tumbled down a mudslide for Kathleen Turner in Romancing the Stone. She did the stunt driving for Shirley MacLaine in the Oscar-winning 1983 film Terms of Endearment. She also did stunts in such films as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Minority Report, and more recently, The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift and The Amazing Spider-Man.

Over the years, Epper did get hurt a few times on set, as she told Dan Rather in 1979 on CBS Sunday Morning. She was trapped in a burning cabin for the TV show Lancer, and she was smashed on the head with a heavy picture frame in the movie Foxy Brown. But for the most part, Epper avoided any serious injuries.

Rowe says Epper always regaled others on set with stories about making movies, and gently offered advice. And even in her later years, Epper continued working. “She’d be the grandma you saw on TV that got knocked down in the grocery store,” says Rowe. “She had a long and varied career and she was tough as nails…she was just a hoot. “

Carter called Epper a real-life Wonder Woman. “When you accomplish, with grace and honor, like she did,” she said, “That is the pulse factor of a Wonder Woman, someone that reaches out to help others, to include others, to change the world around them, in small and large ways.”

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Challengers Movie Review

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Republicans brace for spring legislative sprint with one less GOP vote

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAt least four dead in US after dozens of tornadoes rip through Oklahoma

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoStefanik hits special counsel Jack Smith with ethics complaint, accuses him of election meddling

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAnti-Trump DA's no-show at debate leaves challenger facing off against empty podium

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAs student protesters get arrested, they risk being banned from campus too

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoNine on trial in Germany over alleged far-right coup plot

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Police Arrest Columbia Protesters Occupying Hamilton Hall