Finance

Generating Finance for Blue Economy Transition | ORF

Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

1. Challenge

‘Blue Economy’ Defined

Blue Economy implies the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth as well as improved livelihoods and jobs, while preserving the health of the marine ecosystem. Blue Economy activities recognise the ocean as a critical space for sustainable development, balancing conservation with resource use and promoting regeneration. These activities decouple socio-economic development from environmental degradation, thereby contributing to marine ecosystem protection, encouraging sharing of benefits, promoting equity in access and inclusive growth, enhancing abundance, and leading to improved wellbeing.

Blue Economy in the G20 Countries and Current Threats

The G20 is made up of coastal nations, comprising 45 percent of the coastline and 21 percent of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) globally. Maritime activities play a crucial role in the economic growth of the G20 countries through international shipping, tourism, providing natural resources, and fossil fuels. They contribute to food and energy security and supporting livelihoods through ship building, fishing, maritime services, and other ancillary industries. The global ocean produces over half of the world’s oxygen, acts as a heat sink, and mediates global weather. Marine and coastal ecosystems provide critical coastal protection, carbon storage, and sequestration. The ocean also provides non-material benefits such as a communal identity, recreation, aesthetic, and scientific benefits, and is part of humanity’s spiritual and cultural heritage.

Threats to coastal and marine ecosystems emerge from human pressures including marine pollution, climate change, overfishing, unsustainable coastal development, gaps in ocean governance, poor management, lack of enforcement capacity, and the primacy of economic growth over other goals. Among other deleterious effects, this leads to the degradation of natural capital and decreasing resilience. Further, there are several direct and indirect synergies between SDG 14 (‘Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development’) and other SDGs. Considering the centrality of the global ocean in delivering sustainable development, transitioning to the Blue Economy is vital for the G20 countries.

Large financing gaps

According to the WWF, the ocean’s total asset base is at least US$24 trillion, with an annual contribution of US$2.5 trillion to the global economy.[1] Other studies estimate the annual contribution at US$1.5 trillion.[2] Indeed, life on earth is dependent on the oceans, and healthy marine and coastal ecosystems deliver higher economic and social benefits. While conventional maritime sectors continue to attract capital, investment in the Blue Economy is extremely inadequate, with estimates indicating that only US$13 billion were invested in the last 10 years.[3] The World Bank PROBLUE program—an Umbrella Multi-Donor Trust Fund to help countries develop their Blue Economy—has received US$200 million, which is a small percentage of the US$7-billion active ocean projects portfolio of the World Bank.[4] The financing gap for establishing and maintaining MPAs to reach 10 percent of the protected area (Target 14.5 of SDG 14) is USD$7.7 billion per year, and the required investment is 20-30 times that of its current value.[5] Extrapolating this to meet the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s target of ensuring 30 percent protected areas (inland water, coastal, and marine areas) by 2030 suggests a USD$27.7-billion per year financing gap.

Absence of a Blue Economy financing framework and global standards

Financing for the Blue Economy suffers from a lack of frameworks, global standards, consistent methodology, and financial incentives towards guiding investors, thereby limiting effective decision-making.[6] A number of frameworks, including the Blue Economy Sustainability Framework, inform investment decisions across Blue Economy sectors in the European Union. Additional proposed frameworks include the Principles for Investment in Sustainable Wild-Caught Fisheries for investing in sustainable fishing practices, the Ocean Finance Framework (ADB), and a Blue Economy Development Framework (World Bank).

The International Finance Corporation has combined the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles (endorsed by 70 institutions) and the Sustainable Ocean Principles (endorsed by 150 companies) into the Guidelines for Financing the Blue Economy. Although these principles and guidelines offer familiarity advantages and are adaptable to various national and regional plans, they face challenges of divergent mechanisms, inadequate information, and poor awareness. To begin with, there is no consensus yet on what constitutes blue financing, nor the classification of activities and regulatory mechanisms,[7] and which metrics should be used to measure investment impact. This leads to a lack of consistency, transparency, and accountability, which undermine the credibility of investing.

Harmful subsidies undermining investments

The Blue Economy transition is also hindered by harmful subsidies for maritime sectors that undermine ocean health. While the full extent is not quantified, global annual fishing subsidies were estimated at US$35 billion in 2018, which contributed to significant overfishing and illegal fishing.[8] The International Monetary Fund estimated over US$5.9 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies for 2020, and these increased further in 2021-23, impacting ocean health.[9] This excludes the direct contributions of the plastic industry and fertiliser subsidies to marine pollution. Capacity-enhancing fishery subsidies damage fish stocks, risk species extinction, undermine economic viability for small-scale fisheries by promoting inequality, and threaten livelihoods and food security for fishing communities. Harmful subsidies counteract philanthropic and public investment in marine conservation, while a lack of incentives limits Blue Economy investments.

Low bankability of projects

Despite marginally increasing finance flows, there are few investment-grade projects aligned with Blue Economy principles, financing guidelines, and investor requirements. In contrast to terrestrial-based project funding, which have longer track records, most maritime projects generate poor financial returns, lack appropriate size, have high risk-return ratios, and fail to attract capital at a sufficient scale. Stakeholders often have limited Blue Economy awareness and understanding, and little capacity to identify suitable investable opportunities. Poor marine governance and the inherent nature of projects, which often deliver public goods, are some other factors that hinder high financial returns, leading to low bankability of Blue Economy projects.

Lack of commercial interest and private finance

Commercial lenders cite the lack of adequate profits and incentives, insufficient investment-ready marketable projects, limited financial resources, and higher risks due to information gaps. This leads to a lower propensity for funding projects,[10] which is compounded by a lack of case studies of successful replicable projects. Analyses of voluntary Blue Economy investment commitments reveal that these were mostly from NGOs and governments, with very few coming from private institutions or public-private partnerships.[11] This is supported by a survey of Blue Economy investors, which noted that 75 percent of investors had not assessed their investment portfolios for impacts on ocean sustainability and 20 percent were unaware of ocean-related investment risks exposure.[12]

Poor data availability, technical constraints, and capacity limitations

Financing for transition to Blue Economy is further hindered by poor data availability, technical constraints, and capacity limitations, including the non-availability of accurate marine surveys, irregular threat assessment, limited technical training, lack of ocean technology, and poor political support to prioritise investments. Uncertainty around coastal/marine responsibilities, jurisdiction, and tenure, including private and/or communal property rights, also limits investors. Poor expertise about newer financing mechanisms, experience, financial and business literacy, and lack of entrepreneurship also creates barriers.

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 can catalyse transition finance for investing in sustainable fisheries, integrated coastal zone management, improved waste-management facilities on land, sustainable marine and coastal tourism, clean maritime transport, and offshore renewable energy projects.

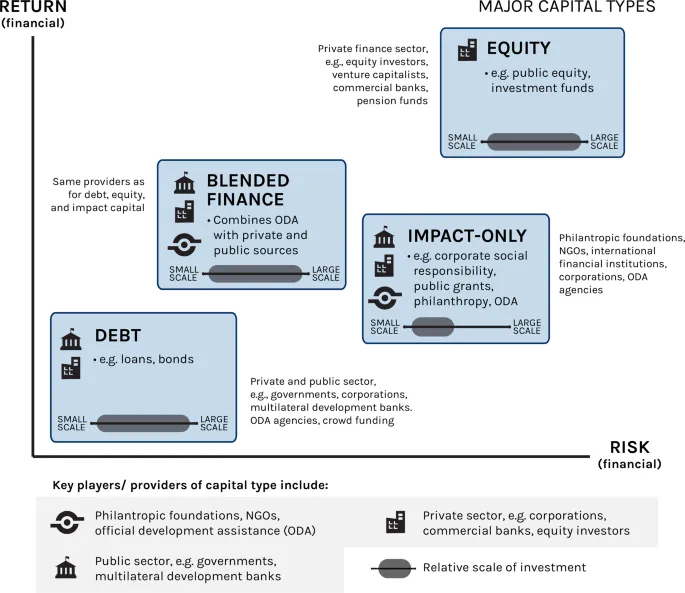

Although there are several financing sources (see Figure 1), it is important to correctly match projects to the type of capital. Projects that have potential for generating competitive market returns should be fully funded by private debt and equity. Public goods projects unlikely to generate direct financial returns, such as enhanced ecosystem services, are best funded from public sources, development finance, and philanthropic funds. Blended finance approaches that integrate commercial funding from private investors and institutions are a better choice for projects that generate below-market returns and can be used to de-risk such investments by leveraging grants from public or philanthropic sources. This lowers overall funding cost, and project development can be covered through grant-funded technical assistance. Recent examples include the Global Fund for Coral Reefs and the Subnational Climate Finance Fund, both of which attracted the Green Climate Fund junior capital.

Figure 1. Capital Types With Risk-Return Characterisation and Their Providers[13]

The G20 can help promote Blue Economy investment with select financing mechanisms.

Debt-for-nature swaps for marine protection

Debt instruments for Blue Economy financing are particularly attractive for countries with limited access to overseas development assistance. However, growing debt limits the ability of many countries to invest in the Blue Economy. Debt-for-nature swaps, a financial mechanism whereby a country’s external debt is restructured on more favourable terms in return for a commitment to invest in marine protection, such as through the establishment of MPAs, is gaining traction. Figure 2 shows a basic model wherein a creditor government cancels the sovereign debt of another country and the debtor government uses money in the local currency to fund environmental projects. In the tripartite model, an NGO is an intermediary to execute projects. As seen in Figure 1, this variation of debt-funding can be used for conservation projects which have low financial risk and return.

Figure 2. Bilateral and Tripartite Models of Debt-for-Nature Swap[14]

Blue Bonds

Blue bonds are debt instruments where issuing authorities (e.g., government, banks) raise capital to finance Blue Economy projects with the objective of generating project earnings, while seeking to make an impact using the proceeds.[15] Blue bonds are a subset of green bonds where proceeds should exclusively be used for marine-protection projects. These instruments are being increasingly used by multilateral financial institutions such as the Nordic Investment Bank, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the Bank of China as effective instruments for funding a pool of projects, such as addressing marine plastic waste and upgrading wastewater treatment plants.

Blue Loans

A blue loan enables borrowers to raise funds to support Blue Economy activities. Such a loan is aligned to ‘green loan principles’, and proceeds are exclusively dedicated to finance or refinance activities towards ocean protection and/or improved water management.[16] Blue loans for investing in projects such as diverting plastic waste from the ocean, improving wastewater management, and increasing access to capital for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are emerging as a source of Blue Economy financing.

Conservation Outcome-Based Financing

Outcome-based financing instruments such as sustainability-linked loans and bonds can be alternative mechanisms to transfer the risk of funding conservation from donors to impact investors by linking predetermined conservation targets to financial returns. The Wildlife Conservation Bond for the protection of rhinos in South Africa can be considered to achieve outcomes such as the protection of a specific marine species, conservation of small-scale fisheries, or prevention of marine biodiversity loss.

Parametric Insurance Products

Traditional insurance covers the risk of maritime infrastructure loss such as ports and transport. Parametric insurance triggered by an event is also emerging. One example is the Mesoamerican Reef Insurance Programme, which covers hurricane risk and provides support for reef restoration and local economic recovery of coastal communities. Other solutions include weather index based parametric insurance for small-scale fisheries[17] and ocean carbon sink insurance policies,[18] which provide compensation when specific marine environment damage to local species such as kelp, shellfish, or algae lead to the weakening of blue carbon sinks.

Lessons from Successful Examples

Successful use examples of Blue Economy financing instruments include the Seychelles’ debt-for-nature swap, where the country’s US$21.6 million external debt was restructured for a protection commitment of 30 percent of Seychelles EEZ by channelling funds for marine conservation and climate adaptation. Subsequently, the Seychelles issued a US$15-million sovereign blue bond, and proceeds are being used to support the transition to sustainable fisheries. These deals have led to increased government fiscal space, ability to disburse US$700,000 annually in grants to support ocean conservation and climate action, and a US$12 million revolving fund to provide private-sector blue loans. Debt-for-nature swap and blue bond models were replicated in Belize with a US$363 million ‘super blue bond’ in 2021 and in Barbados with a US$50-million debt-for-nature swap.

In investigating novel financing instruments, it is important to consider whether they are addressing a gap in Blue Economy financing with well-defined indicators of success. To call a bond ‘blue’, at least 90 percent of the funds need to be allocated towards promoting Blue Economy projects. Unfortunately, regulations do not exist yet to hold bond issuers legally accountable for using proceeds in an arbitrary manner. Thus, there is a real risk of ‘blue-washing’.[19] Lack of transparency, participatory approaches to obtain prior and informed consent of citizens, questions on mechanisms used to disburse funds, and powerful NGOs with annual budgets surpassing government departments and other civil society organisations are some thorny issues that need to be adequately recognised and addressed.[20]

Till date, there is no gainsaying that blended finance has not delivered at the required scale for funding Blue Economy innovations, and public funds will continue to play a key role. Therefore, these successful examples cannot be viewed as a silver bullet, but countries require a mosaic of financing mechanisms while addressing simultaneous challenges.

3. Recommendations to the G20

A Policy Brief published in 2021 under Italy’s G20 Presidency[21] focused on common approaches for integrating nature into ocean accounting and facilitating increased financial flows. In 2022, another Policy Brief, published by T7 Germany[22] proposed redesigning and scaling-up blue finance by increasing early-stage funding and integrating ocean criteria into sustainability finance frameworks. In the same year, a Policy Brief under Indonesia’s G20 tenure[23] recommended mainstreaming finance by integrating Blue Economy criteria into financial processes and proactively financing activities with concerted government action, regulators, the private sector, and development agencies. Building on these earlier proposals, this Policy Brief recommends the following to enable Blue Economy transition finance:

- Adopt standards, framework, and guidelines. Adopt transparent and robust standards, frameworks, taxonomy, and metrics for the integration of Blue Economy principles and approaches into emerging governance, policies, and decision-making processes to ensure that financing adheres to promulgated guidelines from the beginning.

- Strengthen oversight. Strengthen ESG criteria, integrity, and compliance for Blue Economy financing projects while streamlining impact assessment processes. All ocean biomes should be included in disclosure frameworks such as the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TFCD) and the Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TFND), and ocean considerations should be fully integrated for reporting under International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) disclosures.

- Eliminate harmful subsidies. Eliminate regressive subsidies promoting fossil fuels, single-use plastics, overfishing, and marine pollution. Align taxes and enhanced producer liability frameworks with ocean health ambitions.

- Mobilise capital by deploying innovative financial instruments. Identify and develop a pipeline of bankable projects for scalable or replicable market-ready opportunities using targeted financial instruments. This could include the deployment of appropriate capital market instruments, such as dedicated blue bonds, as well as the strengthening of domestic capital market instruments.

- Implement cohesive policies and coordinated responses. Implement coordinated responses via public funding while focusing on marine ecosystem restoration/area protection and the resilience of coastal communities. The coordination of multilateral development finance institutions and national finance bodies needs to be strengthened. The global commitment to protect 30 percent area by 2030 should be leveraged to deliver targeted Blue Economy finance.

- De-risk investments. De-risk public and private investments by defining and adopting project selection criteria, use of funds, equitable sharing of benefits, effectiveness reporting, and mandating external review of projects. Guarantee structures and de-risking formats, whether through insurance mechanisms or through blended finance support, such as by the Green Climate Fund.

- Incentivise private finance. Effectively enable policy, legislation, and regulatory mechanisms to incentivise private-sector financing for the protection of natural capital while generating financial returns. This includes stopping the insurance of non-compliant activities and sustainability-linked covenants for bank lending. New insurance products for marine ecosystems and increased effectiveness of the parametric approach can also incentivise private finance.

- Increase partnerships to build capacity. Collaborate with relevant actors and stakeholders for sharing data and best practices, capacity building through training for improving knowledge-base, technical cooperation, and technology innovation to help bridge information gaps and strengthen partnerships among the G20 countries. The Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA) is one example of how governments, project operators, NGOs, and large financial institutions can cooperate to deliver solutions.

The G20 must continue to work on issues raised in earlier years, as none of that work is fully implemented yet. However, the above recommendations go beyond attempts of just mainstreaming Blue Economy transition finance. Proactively engaging with all economic actors, including those that negatively affect ocean health, and focusing on areas most in need of adaptation, provides the opportunity to overcome hurdles and jointly deliver rapid transition pathways for Blue Economy financing. Such public-private partnerships need to be supported by G20 governments as well as international financial mechanisms, drawing on recent experiences in innovation. A strong commitment to such integrated approaches to deliver Blue Economy transition finance will be key to scaling up ocean-climate solutions and will be of immense relevance ahead of the UNFCCC COP28.

Endnotes

[1] Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Reviving the Ocean Economy: The Case for Action – 2015 (Geneva: WWF International, 2015).

[2] OECD, The Ocean Economy in 2030 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2016).

[3] U. Rashid Sumaila et al., Ocean Finance: Financing the Transition to a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2020).

[4] “The World Bank’s PROBLUE Program and PROBLUE: Supporting Integrated and Sustainable Economic Development in Healthy Oceans,” The World Bank Group, last modified July 25, 2022.

[5] Sumaila et al., Ocean Finance

[6] Jack Dyer, How to Understand, Access Finance and Invest in the Caribbean and Global Blue Economy (South Africa: Blue Economy Future, 2021).

[7] Nagisa Yoshioka et al., “Proposing Regulatory-Driven Blue Finance Mechanism for Blue Economy Development,” ADBI Working Paper 1157, 2020.

[8] “UNCTAD14 Sees 90 Countries Sign up to UN Roadmap for Elimination of Harmful Fishing Subsidies,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, last modified July 21, 2016.

[9] “Fossil Fuel Subsidies,” International Monetary Fund, last modified September 20, 2019.

[10] “Will Blue Finance Fulfil Its Potential?,” World Ocean Initiative, last modified January 22, 2020.

[11] “Community of Ocean Action on Sustainable Blue Economy – Interim Assessment,” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and World Resources Institute, accessed March 1, 2023.

[12] “Is the Sustainable Blue Economy Investible?,” Credit Suisse, last modified January 20, 2020.

[13] U. Rashid Sumaila et al., “Financing a Sustainable Ocean Economy,” Nature Communication 12, no. 1 (2021): 3259.

[14] Matthew R. Claeson, “Debt-for-Nature Swaps: A Concise Guide for Investors,” Lord Abbett Distributor LLC, last modified December 19, 2022.

[15] “Sovereign Blue Bonds – Quick Start Guide,” Asian Development Bank, last modified September 2021.

[16] “Guidelines Blue Finance – Guidance for Financing the Blue Economy, Building on the Green Bond Principles and the Green Loan Principles,” International Finance Corporation, last modified January 2022.

[17] “Action Report for 2022- Investing in Coastal Communities and the Ocean,” Ocean Risk and Resilience Alliance, accessed March 11, 2023.

[18] “Ping An Launches First Ocean Carbon Sink Index Insurance Policy for Marine Ecosystem Protection,” PingAn, last modified February 14, 2023.

[19] Natasha White, “Debt Swaps Called Out by Barclays Analysts Ignite ESG Debate,” Bloomberg, last modified January 31, 2023.

[20] “Financing the 30X30 Agenda for the Oceans: Debt for Nature Swaps Should Be Rejected,” Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements, last modified December 06, 2022.

[21] Paul De Noon et al., Fixing Financial, Economic and Governance Structures to Save Forests and the Ocean and Enhance Their Contributions to Climate Change Solutions (Italy: The Think20, 2021).

[22] Mirja Schoderer et al., Safeguarding the Blue Planet – Eight Recommendations to Sustainably Use and Govern the Ocean and its Resources (Bonn: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2022).

[23] Dennis Fritsch et al., Financing the Sustainable Blue Economy (Indonesia: The Think20, 2022).

Finance

NYS public-campaign-finance fraud exposes state board’s utter incompetence

New York state’s new public-campaign-funding scheme couldn’t be more ripe for fraud and abuse.

In the lead-up to the June 25 primaries, the state’s Public Campaign Finance Board doled out more than $8.6 million in matching-fund payments to 69 state legislative candidates — with no real guardrails to prevent shady candidates from ripping off the taxpayers.

The board looks to be as feckless as the Cannabis Control Board, which not-so-coincidentally was also launched under Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

In a fit of responsible local journalism, The New York Times has chronicled, how Dao Yin, a Flushing Democrat who filed to run for state Assembly, apparently used straw donors to scam the system out of $162,800 in taxpayer-financed matching funds.

Naturally, New York funds the most generous statewide public-matching-funds system in the nation: A single $50 donation nets $600 in public funds while a maximum $250 contribution garners $1,800.

For contributions between $5 and $250 from legislative district residents, the public match is 12-to-1 for first $50, 9-to-1 for next $100 and 8-to-1 for the following $100.

And the board’s “oversight” doesn’t seem to go much beyond sending out the checks.

The Times’ review of Yin’s contribution cards found a host of red flags:

- At least 48 alleged donors who said they never heard of Yin denied making the alleged contributions and said their signatures were forged; some said they no longer resided at the addresses listed.

- Almost $28,000 in cash coming from small donors.

- Most of his his donations, 80%, came in cash — about 15 times the average cash share of contributions for Assembly candidates participating in the system.

- Multiple “donor” records missing key required contact information or with other errors.

- Dao Yin was the campaign treasurer, chief fundraiser and candidate.

The board liaison to the Yin campaign missed all of this — and took Yin’s word that he sent so-called “good-faith” letters to validate questionable donors.

To be fair, the city Campaign Finance Board may have been as lax: For his 2020 borough president and 2021 City Council campaigns, he got over $1 million in city matching funds.

(The city board also needs to complete its 2023 City Council campaign audits, too, as the 2025 election season is upon us.)

The state idiocy was baked in from the start:

An April 2018 Siena poll found that nearly two-thirds of New York voters opposed public funding of state elections when told it would cost an estimated $100 million every two years — at least.

But Cuomo and the Legislature went ahead anyway, creating a commission to devise the system in March 2019.

They stacked it with political operatives, such as election lawyer and former de Blasio fixer Henry Berger and state Democratic Party boss Jay Jacobs — for whom Cuomo suspended a state regulation that prevented political party bosses from serving in “policy making” posts in state government.

Today, the PCFB chair and vice chair are former state lawmakers Barbara Lifton (D) and Brian Kolb (R): That is, bipartisan patronage posts.

But the geniuses also left basic guardrails missing, such as:

- Mandatory post-election audits of every campaign.

- Sufficient staff to review and monitor campaign filings.

- The board has no independent subpoena power to pursue rogue campaigns.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer money for political appointees to dole out is a magnet for the corrupt.

The state program is a boon for incumbent lawmakers and their unscrupulous challengers — and another needless drain on taxpayers’ wallets.

Finance

NYS' $100M program to publicly finance campaigns prompts an emergency fix

ALBANY — New York State has issued an emergency order to better verify contributors to campaigns before the state matches cash contributions under the new public campaign financing program.

The order was made two days after the June primary and in the midst of the program’s biggest rollout leading to the November legislative elections. It followed a media report that claimed the system was abused by an Assembly candidate who secured nearly $163,000 in taxpayer funds under the program, some of it with cash donations without a way to verify or contact the contributor.

The emergency amendment approved by the New York State Public Campaign Finance Board on June 27 requires that “contribution cards” that were already required for cash donations must include a phone number or email address so contributors can be verified.

The State Legislature created the program to limit the influence of wealthy donors. This election year, the first major use of the program, has drawn 316 candidates vying for 213 state legislative races. They have qualified to receive part of $100 million in state-funded matches to encourage small donations, $5 to $250, from individuals.

WHAT TO KNOW

- The state has issued an emergency order to better verify contributors to campaigns before the state matches cash contributions under the new public campaign financing program.

- The amendment, which came after a media report of abuse of the system, requires that “contribution cards” for cash donations include a phone number or email address so contributors can be verified.

- This election year is the first major use of the program and has drawn 316 candidates vying for 213 state legislative races. They have qualified to receive part of $100 million in state-funded matches.

The response to the program by challengers and incumbents has exceeded the predictions of even the program’s most ardent supporters, but hasn’t come without problems.

The amendment came after The New York Times reported on fundraising by Assembly candidate Dao Yin in the June 25 primary. The Times said the Queens Democrat used “fake donations and forged signatures” in a campaign that received almost $163,000 in taxpayer money under the new public finance system.

Yin denied he faked contributions. “Everything we say is distorted” in the news media, Yin told Newsday.

In a written statement, he said his campaign workers “adhered to all the necessary procedures to meet the matching funds requirements. In the event of any inadvertent errors, they are actively collaborating with the New York State Public Campaign Finance Board to rectify them.”

The amendment resolution approved by the campaign finance board said, “Mandating that the contributor’s phone number or email address be provided on a contribution card would greatly assist in the audit and process of contributions in order to pay matchable funds, but are not currently required to be provided.”

“The matching claim would be denied until that information is supplied,” said William J. McCann, co-program manager of the public campaign finance unit, at the June 27 meeting.

The amendment also ends the use of “good-faith letters” that campaigns can attach to donations with too little information to verify the identity of the contributor. Campaigns could provide the letter to say they tried but failed to get the information. Before the amendment, that could have allowed a campaign to receive a matching fund from the state.

“The implementation of the policy of accepting good-faith letters was not a regulation, but rather adopted during program development by bipartisan staff,” said Kathleen McGrath, spokeswoman for the state Board of Elections. “The good-faith letters were to capture a phone number or email address of a cash contributor if not included on the associated contribution card. These data points were not required to be submitted by a committee under the statute for public funds matching, but were an effort by the [state Public Campaign Finance Board] to go above and beyond in auditing submissions. “

With the amendment, “The policy of accepting good-faith letters has been rendered moot,” McGrath said.

The state Board of Elections didn’t immediately release data on the number of letters of good faith that have been accepted. Newsday has requested the data under the Freedom of Information Law.

Two other complaints were handled this year as part of the public campaign financing program, according to Public Campaign Finance Board records.

In April, the board received a complaint that Democrat Gabi Madden’s campaign violated state election law by using a prohibited “game of chance” as a fundraiser in her unsuccessful race to represent parts of Dutchess and Ulster counties in the Assembly. In June, the board dismissed the case without further enforcement action after the campaign refunded the contributions.

In May, the board investigated a complaint that Madden’s campaign failed to report expenditures or in-kind contributions for use of the campaign office. In June, the board dismissed the case without further enforcement action after the campaign amended its required financial disclosures.

At the same June 27 meeting in which the state Public Campaign Finance Board approved the emergency amendment, the board also authorized a referral to law enforcement in another case without saying who or which campaign was the subject of the referral.

McGrath wouldn’t comment.

Board vice chairman Brian Kolb, a Republican who when he served in the Assembly opposed public financing of campaigns, defended the rollout.

“We have a very solid process in place,” Kolb told Newsday. “With any new program, you might find some things that we probably should do a little bit differently … but if there are any issues, we fix them and that’s the whole approach.”

Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group, which supported public financing of campaigns, said “it’s not surprising there are hiccups the first time through.”

He said the Legislature should review this first year’s performance to determine if any changes are needed to improve accountable and thwart “people who are looking to game the system.”

Finance

Maple Finance TVL More Than Doubles Leading Up to New Retail Arm – The Defiant

The DeFi protocol hit all-time high TVL and revenue in June.

Maple Finance’s total-value locked (TVL) growth is accelerating after the launch of its retail-focused product, Syrup.fi.

Maple’s TVL increased by 123% in the second quarter, hitting an all-time high of $230 million, according to Dune Analytics. The protocol’s quarterly revenue also jumped by 39%. Maple’s strong performance in June was capped off with the launch of Syrup.fi on June 25. The rest of the DeFi market increased by roughly 9% in the same time period, per DeFiLlama.

The growth spurt is indicative of the demand for institutional-grade products leveraging high yield and real world assets (RWAs) as well as the anticipation for a retail extension of Maple Finance. The current structure is also well incentivized, with Maple users earning up to 23% on digital assets, and Syrup users accruing “Drips”, which are akin to points.

Co-founder Joe Flanagan told The Defiant, “Maple’s growth is attributed to our secured lending products that provide yield from loans to the largest institutions fully backed by digital assets.”

He continued, “we are providing the best risk-adjusted yield in the space and people are starting to recognize it.”

Maple Finance is a decentralized finance (DeFi) market designed to connect accredited investors with institutional lenders and borrowers. Maple is only available to users who have performed know-your customer checks and meet regulatory standards for the product.

Maple’s resurgence comes after its TVL got crushed during the FTX fallout, when $36 million worth of loans owed to Maple were defaulted on.

Retail-Focused Syrup.fi

In addition to its institutional product, the team has recently launched a retail-focused arm, dubbed Syrup.fi. The team is gradually rolling out Syrup.fi, which has accrued more than $13 million in TVL since its launch on June 25.

Syrup offers permissionless access to Maple’s yield, which is generated from collateralized lending to institutions. The product will also return composable LP tokens in the form of syrupUSDC, which can be utilized elsewhere in DeFi.

Syrup users will be accumulating Drips through Maple’s muti-season early access phase. Drips will entitle users to an allocation of Maple’s upcoming Syrup token, which is expected to migrate with their MPL token in Q4 2024.

High-Yield Secured Pool

Maple’s recent outperformance began prior to the launch of Syrup.fi, with the launch of its High Yield Secured pool, touting a target of 15% net APY.

The protocol’s secured lending arms are over-collateralized with liquid digital assets such as BTC, USDC, and ETH. Currently, Maple’s secured pools make up $147 million of its $230 million TVL.

Maple Cash is the platform’s RWA pool that is backed by short-dated U.S. Treasury bills. Maple Cash’s TVL has doubled since March, increasing to $20 million from $11 million, however it does still sit below its all-time high TVL of $31 million from October 2023.

Syrup’s season one will end on July 31, with the MPL token migration slated for Sept. 30.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoToplines: June 2024 Times/Siena Poll of Registered Voters Nationwide

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoThe many faces of Donald Trump from past presidential debates

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBolivia foils coup attempt: All you need to know

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTension and stand-offs as South Africa struggles to launch coalition gov’t

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week agoExercise may lower the ALS risk for men — but not women: new study

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court rules to allow emergency exceptions to Idaho's abortion ban

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoVideo: How Blast Waves Can Injure the Brain

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court denies Steve Bannon's plea to stay free while he appeals

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/UIF23H3DKJMW3LTMH5LZDJ4QYY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/VTH2ZNGJIZLQFJWDPHV5G2DYTA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/W736DGWI65KTNLUVAY26Y427ZA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/4DA4TEELSZP3XFFBOVOPCV5MCU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/OL56GGUB5JNJZMX563TMZYLAB4.jpg)