Fifteen years separated “The Godfather Half II” from “Half III,” and the years confirmed. The sequence’ director, Francis Ford Coppola, enriched the latter movie with each the life expertise (a lot of it painful) and the expertise of his work on different, usually daring and distinctive movies with which he crammed the intervening span of time. Against this, James Cameron, who delivered the unique “Avatar” in 2009, has delivered its sequel, “Avatar: The Approach of Water,” 13 years later, by which time he has directed no different characteristic movies—and, although he probably has lived, the only real expertise that the brand new film suggests is a trip on an island resort so distant that few outdoors guests have discovered it. For all its sententious grandiosity and metaphorical politics, “The Approach of Water” is a regimented and formalized tour to an unique pure paradise that its choose company battle tooth and nail to maintain for themselves. The film’s bland aesthetics and banal feelings flip it into the Membership Med of effects-driven extravaganzas.

The motion begins a few decade after the tip of the primary installment: the American-born Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) has forged his lot with the extraterrestrial Na’vis, having saved his blue Na’vi type, taken up residence with them on the plush moon of Pandora, and married the Na’vi seer Neytiri (Zoe Saldaña), with whom he has had a number of kids. The couple’s foster son, Spider (Jack Champion), a full-blooded human, is the organic baby of Jake’s archenemy, Colonel Miles Quaritch, who was killed within the earlier movie. Now Miles has returned, type of, within the type of a Na’vi whose thoughts is infused with the late colonel’s reminiscences. (He’s nonetheless a colonel and nonetheless performed by Stephen Lang.) Miles and his platoon of Na’vified people launch a raid to seize Jake, who, together with his household, fights again and will get away—all however Spider, whom Miles captures. The Sully clan flees the forests of Pandora and reaches a distant island, the place a lot of the film’s motion takes place.

The island is the house of the Metkayina, the so-called reef folks, who—befitting their almost amphibian lives—have a greenish forged to distinction with Na’vi blue; in addition they have flipper-like arms and tails. They’re an insular folks, who’ve remained undisturbed by “sky folks”—people. The Metkayina queen, Ronal (Kate Winslet), is cautious of the newcomers, fearing that the arrival of Na’vis searching for refuge from the marauders will make the islands a goal, however the king, Tonowari (Cliff Curtis), welcomes the Sullys nonetheless. Unsurprisingly, the foreordained incursion takes place. An expedition of predatory human scientists arrive on a quest to reap the dear bodily fluid—the sequel’s model of unobtainium—of big sea creatures which can be sacred to the Metkayina. The invading scientists be a part of the colonel and his troops within the hunt for Jake, leading to a colossal sequence that mixes the 2 adversaries’ long-awaited hand-to-hand showdown with “Titanic”-style disaster.

The interstellar navy battle is the mainspring of the story, and a hyperlink in what is meant to be an ongoing sequence. (The following installment is scheduled for launch in 2024.) Nevertheless it’s the oceanic setting of the Metkayina that gives the sequel with its essence. Cameron’s show of the temptations and wonders of the Metkayina lifestyle is directly the dramatic and the ethical heart of the film. The Sullys discover welcoming refuge within the island group, however in addition they should endure initiations, ones which can be centered on the kids and teen-agers of each the Sullys and the Metkayina ruling household. This comes full with the macho posturing that’s inseparable from the cinematic land of Cameronia. Two boys, a Na’vi and a Metkayina, battle after one calls for, “I want you to respect my sister”; afterward, Jake, getting a glimpse at his bruised and bloodied son, is delighted to study that the opposite boy acquired the worst of it. Later, when, throughout fight, bother befalls one of many Na’vi kids, it’s Neytiri, not Jake, who loses management, and Jake who provides her the outdated locker-room pep speak about bucking up and conserving concentrate on the battle at hand. The movie is stuffed with Jake’s mantras, one among which works, “A father protects; it’s what provides him that means.”

What a mom does, beside combating below a father’s command, remains to be doubtful. Regardless of the martial exploits of Neytiri, a sharpshooter with a bow and arrow, and of Ronal, who goes into battle whereas very pregnant, the superficial badassery is merely a gestural feminism that does little to counteract the patriarchal order of the Sullys and their allies. Jake’s assertion of paternal function is emblematic of the thudding dialogue; in comparison with this, the common Marvel movie evokes an Algonquin Spherical Desk of wit and vigor. However there’s extra to the screenplay of “The Approach of Water” than its dialogue; the script (by Cameron, Rick Jaffa, and Amanda Silver) is nonetheless constructed in an uncommon manner, and that is by far essentially the most fascinating factor concerning the film. The screenplay builds the motion anecdotally, with quite a lot of sidebars and digressions that don’t develop characters or evoke psychology however, somewhat, emphasize what the film is promoting as its robust level—its visible enticements and the technical improvements that make them attainable.

The prolonged scenes of the Sullys getting acquainted with the life aquatic are largely ornamental, to show the water-world that Cameron has devised, as when the younger family members study to experience the bird-fish that function the Metkayina’s mode of conveyance; when one among them dives to retrieve a shell from the deep; and when the Sullys’ adopted Na’vi daughter, Kiri (performed, surprisingly, by Sigourney Weaver, each as a result of she’s taking part in a teen-ager and since it’s a special position from the one she performed within the 2009 movie), discovers a passionate connection to the underwater realm, a perform of her separate heritage. The watery mild and its undulations are points of interest in themselves, however the highlight is on the wildlife with which Cameron populates the ocean—most prominently, luminescent ones, comparable to anemone-like fish that mild the way in which for deep-sea swimmers who’ve a religious connection to them, and tendril-like vegetation that develop from the seafloor and function a closing resting place for deceased reef folks.

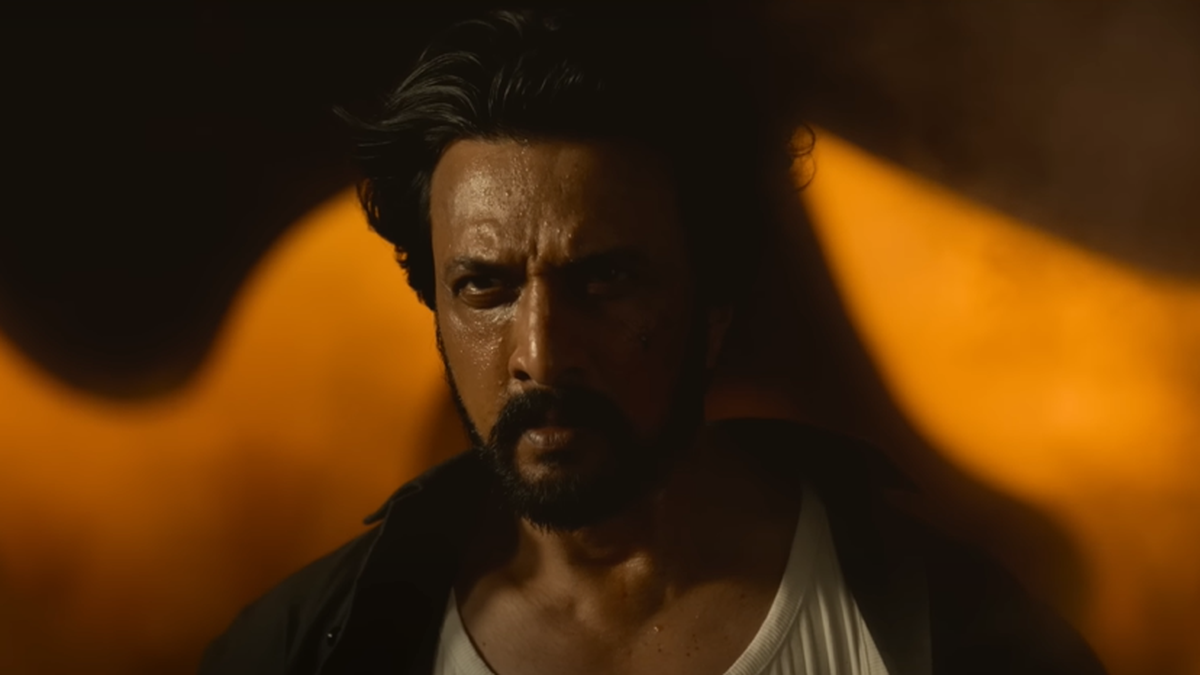

Placing the film’s design within the forefront does “The Approach of Water” no favors. Cameron’s aesthetic imaginative and prescient is reminiscent, above all, of electrical giftwares in a nineteen-eighties shopping center, with their wavery seascapes expanded and detailed and dramatized, with the kitschy colour schemes and glowing settings buying and selling homey disposability for an overblown triumphalist grandeur. It was an enormous shock to study, after seeing the movie, that its aquatic settings aren’t solely C.G.I. conjurings—a lot of the movie was shot underwater, for which the forged underwent rigorous coaching. (To arrange, Winslet held her breath for over seven minutes; to movie, a deep-sea cameraman labored with a custom-made hundred-and-eighty-pound rig.) For all the issue and complexity of underwater filming, nonetheless, the film is undistinguished by its cinematographic compositions, which merely file the motion and dispense the design.

But Cameron’s frictionless, unchallenging aesthetic is greater than ornamental; it embodies a world view, and it’s one with the insubstantiality of the film’s heroes, Na’vi and Metkayina alike. They, too, are works of design—and are equally stylized to the purpose of uniform banality. Each are elongated like taffy to the slenderized proportions of Barbies and Kens, they usually have all the range of sizes and styles seen in swimsuit problems with generations previous. The characters’ computer-imposed uniformity pushes the film out of Uncanny Valley however right into a extra disturbing realm, one that includes an underlying, drone-like inside homogeneity. The near-absence of characters’ substance and inside lives isn’t a bug however a characteristic of each “Avatar” movies, and, with the expanded array of characters in “The Approach of Water,” that psychological uniformity is pushed into the foreground, together with the visible kinds. On Cameron’s Edenic Pandora, neither the blues nor the greens have any tradition however cult, faith, collective ritual. Although endowed with nice talent in crafts, athletics, and martial arts, they don’t have something to supply themselves or each other in the way in which of non-martial arts; they don’t print or file, sculpt or draw, they usually haven’t any audiovisual realm just like the one of many film itself. The principle distinctions of character contain household affinity (as in Jake’s second mantra, “Sullys stick collectively”) and the dictates of organic inheritance (as within the variations imposed on Spider and Kiri by their totally different origins).

Cameron’s new island realm is a land with out creativity, with out customized concepts, inspirations, imaginings, needs. His aesthetic of such unbroken unanimity is the apotheosis of throwaway commercialism, by which thriller and marvel are changed by an infinitely reproducible components, with visible pleasures microdosed. Cameron fetishizes this airtight world with out tradition as a result of, together with his forged and crew below his command, he can create it with no additional information, expertise, or curiosity wanted—no concepts or ideologies to puncture or strain the bubble of sheer technical prowess or criticize his personal self-satisfied and self-sufficient sensibility from inside. He has crafted his personal excellent cinematic everlasting trip, a world aside, from which, undisturbed by ideas of the world at massive, he can promote an unique journey to an island paradise the place he’s the king. ♦

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25742882/DSC_1384_Enhanced_NR.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png)