Business

Why 'economic headwinds' are suddenly to blame for everything

An atmospheric disturbance is whipping through the job market.

When Volvo announced it was cutting more than a thousand jobs last year, its CEO cited a particular phenomenon for the cuts. When the founder of the Messenger announced to his hundreds of employees that they were all laid off without severance, less than a year after the online publication booted up, the same weather pattern got the blame.

Chief executives at accounting firms, cookie companies and Crypto.com have all laid off thousands of workers in the last year, and pointed the finger at one metaphorical culprit: economic headwinds.

The phrase evokes a solemn CEO scanning the sky from the deck of the corporate ship. Eye on the horizon, he senses a change in the weather, a different snap to the rippling canvas, a new chop to the sea. With a grim set to his jaw, he concludes that only one course of action can save the voyage: massive layoffs.

Headwinds have always blown around in business English, but the phrase economic headwinds serves a special purpose: a majestic waving of the hand, an abandon to the fates, an inkling of force majeure.

“It’s a useful term, because we can’t control the wind,” said Thomas C. Leonard, a historian of economics at Princeton University. “If you’re a corporation trying to sell unhappy outcomes to shareholders or regulators, it’s a way of saying it’s a tough environment, but more importantly it’s a tough environment beyond our control.”

It’s a phrase heard often these days in the tech and media sectors, which face real challenges.

Tech companies that could raise and spend cash freely when interest rates were close to zero are struggling to stay afloat. The ad market has hit the doldrums — in part because all those companies that used to have cheap cash to pump into ads now have to keep their powder dry — which has taken the wind out of the sails of many media businesses, which had been facing financial problems for decades. And in L.A., Hollywood studios have been slow to pick up the pace of production after last year’s strikes, as they face questions over the viability of the streaming business model.

Executives in these industries are using the term precisely because of the contrast between their challenges and the wider world, Leonard said.

“The wild thing is, notwithstanding the headwinds in media and technology, the economy is doing unbelievably well,” Leonard said. Inflation is down, unemployment is at historically low levels, the U.S. is outperforming other rich countries, the stock market is booming, and even inequality of wealth and income is falling, Leonard said.

This presents a conundrum for those tasked with swinging the ax: how to explain why your company is ailing when everybody can see blue skies above?

By leaning on economic headwinds, executives can acknowledge a problem while avoiding getting into the messy details — say an outdated business model or internal failings.

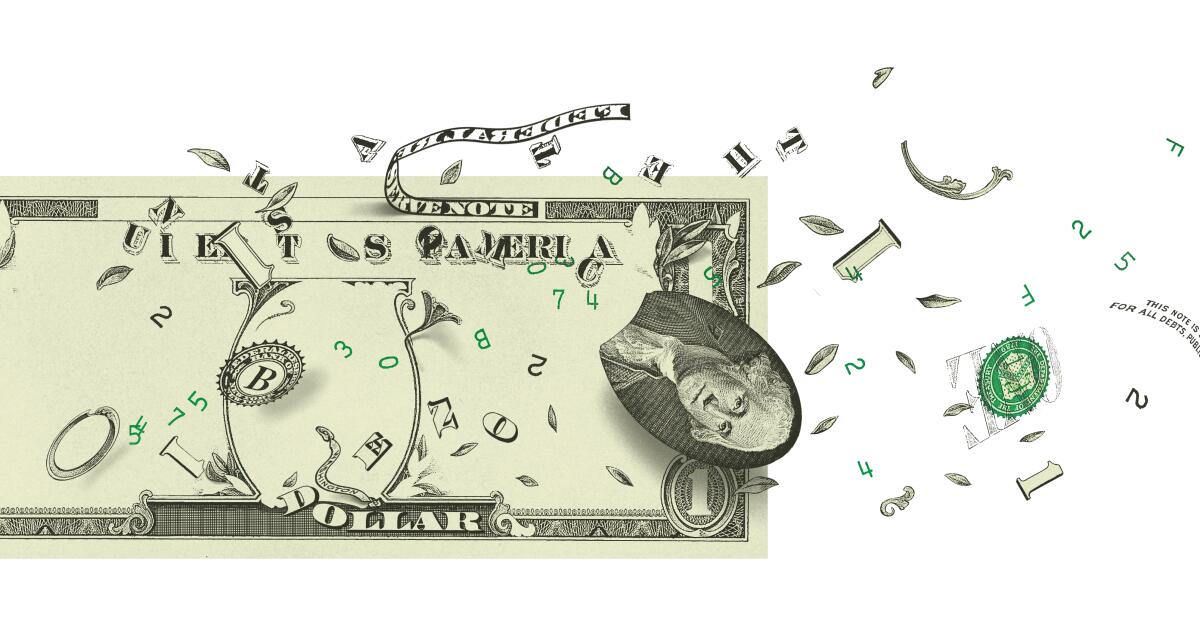

EDGAR, the online database of the Securities and Exchange Commission, confirms that economic headwinds are being evoked more now than ever. In the 2000s, only a slight breeze was blowing, with public filings showing a handful of economic headwinds mentions. Things picked up in 2008 and 2009, as the financial crisis battered corporate America, but conditions seemed to subside in the middle of the last decade.

Then high interest rates rolled in. Since 2022, when the Federal Reserve started ratcheting up the federal funds rate to cool down the economy, EDGAR has been logging record after record. Nearly 500 companies mentioned economic headwinds in 2022. In 2023, that more than doubled to over 1,000.

A scan of the Newspaper Archive, which stretches back to the 18th century, tells a similar story. Through the booms and busts of the Gilded Age, the cataclysms of the Great Depression and the whirlwind of the 1970s oil crisis and stagflation, economic headwinds were barely worth mentioning. Most early mentions are riffs on the metaphor of the ship of state, with entire nations beating against the breeze, or come as puns in stories about airplanes or shipping companies.

But something changes after Y2K. Press usage of the phrase follows the same trajectory as the SEC record — with mentions up through the recession, followed by a dip, and now heading to new heights.

The collective experience of the last few years — pandemic, recession, inflation and now interest rate hikes — may have led to a turning of the rhetorical tides, said Robert Reich, professor of public policy at UC Berkeley and former secretary of Labor.

“The dominant economic assumption for really the entire post-World War II era has been that Keynesian macroeconomic management can tame the uncertainties and extremes of the economy,” Reich said. But since 2020, it’s been difficult to avoid the sense that things are spiraling out of control. “Most people felt at sea, and there’s something not necessarily comforting but seemingly realistic about these metaphors now.”

The economy stopped feeling like a precision machine in need of a tuneup, pointed surely toward growth, and started feeling more like an unpredictable journey to an unknown shore.

“Seeing the economy as a boat, one of those old galleons, or a three-masted schooner, tossed on the great waves of uncertainty and the waves of this roiling system makes much more sense to people,” Reich said.

It’s also “a wonderfully convenient way of avoiding responsibility” when things go sideways, Reich added.

Nautical metaphors are nothing new for the world of commerce — trade, finance and the joint-stock company can all trace their roots to seafaring merchants engaged in risky adventures to haul holds full of goods across the world in capital-intensive ships. And business euphemisms aren’t just limited to the seas. Few parts of the natural world have been spared from the corporate lexicon, with its changing landscapes and seismic shifts. Even the cosmos is fair game, especially in a tech world known for its moon shots and escape velocities.

Such fanciful phrases might serve a more grounded purpose: smoothing things over with investors. Research has shown that euphemisms actually work to soften bad news in the financial markets.

Kate Suslava, a professor of accounting at Bucknell University, spent years tracking how the use of metaphors in corporate earnings calls changes how the stock market reacts to new information. She found that investors aren’t total rubes — the stock prices of companies whose executives used negative metaphors like speed bumps or economic headwinds, or mentioned the need to tighten our belt or sharpen our pencils to get back to work after a series of missteps, indeed went down on the day of the earnings call.

What surprised her was that over the following months, the stock prices of the companies in question continued to drift down. “Investors take it as bad news, but it should be even worse news,” Suslava said. “If the market was efficient, they would completely capture it on the date of the call.”

In other words, a softening metaphor gets investors to under-react to the bad news. “Which is exactly the point of euphemisms,” Suslava said. “They work.”

Business

Warner Bros. Discovery board faces pressure as activist investor threatens to vote no on Netflix deal

Activist investor Ancora Holdings Group is calling on the Warner Bros. Discovery board to consider a revised bid from Paramount Skydance and negotiate with the David Ellison-led company, or it says it will vote no on the proposed deal between Warner Bros. and Netflix.

The Cleveland-based investment management firm released a presentation Wednesday detailing why it believes Paramount’s latest offer could be a superior bid compared with the Netflix transaction.

Ancora said its stake in Warner Bros. Discovery is worth about $200 million, which would make its ownership less than 1% given the company’s $69.4-billion market cap.

Ancora cited uncertainty around the equity value and final debt allocation for the planned spinoff of Warner’s cable channels into a separate company as a factor that could change share valuation. The spinoff is still set to happen under the agreement with Netflix, as the streamer does not intend to buy the cable channels. Paramount has proposed buying the entire company.

The backing of David Ellison’s father, Oracle co-founder Larry Ellison, was a sign of the Paramount bid’s “credibility and executability,” Ancora said, adding that it had concerns about the regulatory hurdles Netflix could face.

Senators grilled Netflix Co-Chief Executive Ted Sarandos last week about potential antitrust issues related to its agreement to buy Warner Bros. Sarandos has said 80% of HBO Max subscribers in the U.S. also subscribe to Netflix and contended that a deal between the two would give the combined company 20% of the U.S. television streaming market, below the 30% threshold for a monopoly.

The investment management firm noted that Paramount is “reportedly viewed as the current administration’s ‘favored’ bidder — suggesting stronger political support,” a nod to the Ellison family’s friendly relationship with President Trump.

Trump has vacillated in his public statements on the deal. In December, he said he “would be involved” in his administration’s decision to approve any agreement, but last week, he said he “decided I shouldn’t be involved” and would leave it up to the Justice Department.

“Paramount’s latest offer has opened the door,” Ancora wrote in its presentation. “There is still a clear and immediately actionable path for the Hollywood ending that all [Warner] shareholders deserve.”

Ancora said it intends to vote no on the Netflix deal and that it also could seek to elect directors at the upcoming Warner shareholders meeting.

Warner said in a statement that its board and management team “have a proven track record of acting in the best interests of the Company and shareholders” and that they “remain resolute in our commitment to maximize value for shareholders.”

Ancora’s presentation does highlight “two primary questions as shareholders approach this deal,” said Alicia Reese, senior vice president of equity research for media and entertainment at Wedbush.

“The biggest question mark is what is Discovery Global worth?” she asked. “The second is how likely is Netflix to pass regulatory scrutiny?”

The firm’s opposition doesn’t necessarily mean the Warner board will change course, but if other significant shareholders take a similar stance, the board likely would need to “meaningfully and proactively engage further to seek more money,” said Corey Martin, a managing partner at the law firm Granderson Des Rochers.

“If I were Paramount … I would view this as a tea leaf that there might be a little bit of an opening here, to the extent we were to be aggressive,” he said. But, “if Paramount wants this company, it’s going to have to blow the Netflix bid out of the water so that there’s no question to the shareholders which bid represents the most value.”

Business

How Chipotle lost its sizzle

Chipotle Mexican Grill, the Newport Beach-based chain known for its bursting burritos and lunch bowls, just finished its worst year ever.

Its same-store sales declined last year for the first time since going public two decades ago. The downturn reflects what analysts say is a broader slowdown in fast casual chains — considered a step above fast food but below full-service restaurants.

In a K-shaped economy where the few with money are still spending while everyone else is anxious about rising prices and keeping their jobs, Chipotle is stuck in a sour spot. It isn’t a destination for the rich. Instead, it is a skippable splurge for those looking to save.

“Our guests [are] placing heightened focus on value and quality and pulling back on overall restaurant spending,” Chipotle Chief Executive Scott Boatwright said last week after announcing earnings.

In an uncertain economy muddied by tariffs and an immigration crackdown, consumers are cutting back on discretionary spending and increasingly seeking the best value on essentials such as lunch and dinner.

Chipotle has boomed in popularity since opening in Denver in 1993. It moved its headquarters to California in 2018.

The burrito staple opened 334 new locations last year, bringing its total to roughly 4,000. The company’s net income was $1.5 billion in 2025, virtually flat compared to the year prior. Its comparable sales lost steam with a roughly 2% decline in 2025 following a 7.4% increase in 2024.

In an earnings call earlier this month, executives estimated that same-store sales would be about flat in 2026, with 350 to 370 new restaurants slated to open.

“As we move into 2026, the consumer landscape is shifting,” Boatwright said.

He tried to suggest that Chipotle customers are from the upward-sloping part of the K in the K-shaped economy, so it will not be planning big price cuts to attract new customers. Boatwright said on the earnings call that 60% of Chipotle’s core customers make more than $100,000 per year.

“We’ve learned the guest skews younger, a little more higher income, and we’re gonna lean into that,” Boatwright said.

The company’s suggestion that it doesn’t plan to do much more for cost-conscious consumers sparked an online debate that the burrito giant is no longer for regular people.

McDonald’s demonstrated the value of offering more value these days. It announced this week that its sales surged after the launch of its $5 meal deal last year, part of broader value wars among fast-food establishments.

Chipotle has tried to offer value by not raising its prices as much as inflation would require, reviving a rewards program, testing a “happier hour” with lower prices and offering smaller portions at lower prices.

Chipotle came under fire in 2024 for dishing out inconsistent portion sizes, but has since recommitted to giving every customer a “generous” helping.

Late last year, Chipotle launched a high-protein menu that includes inexpensive options like a cup of chicken or steak for around $4. Protein has been trending as the rise of GLP-1s have many Americans eating less and focused on getting the most out of their meals.

“This is going to be a marquee year for Chipotle to get back on track,” said Jim Salera, a restaurant analyst at Stephens. “Chipotle has traditionally been much more resilient through ebbs and flows of the consumer, but nobody’s immune.”

The company has weathered other challenges in the past. Its business took a hit when it served tainted food that sickened more than 1,100 people in the U.S. from 2015 to 2018. The company paid a $25 million fine to resolve criminal charges connected with the outbreaks.

Some full-service restaurants are also lowering prices to levels that compete with Chipotle, analysts said. A Chipotle burrito or bowl plus a drink costs around $15, while the value-focused full-service restaurant Chili’s offers a multi-course meal for under $11.

“The pricing advantage that fast casual has relative to other segments has eroded significantly” said Aneurin Canham-Clyne, who covers restaurants for the trade publication Restaurant Dive.

Middle- and upper-income consumers aged 25 to 30 make up a significant share of Chipotle’s business, but many are looking for cheaper ways to get their meals. Fast casual chains have to rely on consumers with a range of incomes, not just the top 20% of households, Canham-Clyne said.

“White collar workers making in the low six figures in major cities who are feeling the heat from services inflation or feeling insecure in their jobs as a result of AI, they’re going to be saving a little bit more money,” he said.

Chipotle shares have fallen more than 37% over the past year, and they are not the only fast casual company to struggle in the stock market. Sweetgreen, headquartered in Los Angeles and catering to a health-conscious Southern California consumer, has seen its shares plummet 80% over the past year. The Mediterranean bowl spot Cava saw shares fall more than 50% over the same time period.

Chipotle shares closed Thursday at $35.84, down 4% for the day.

Canham-Clyne said Chipotle is not yet in dire straits. The brand has proven itself consistent and appealing to those looking for high-quality meals at a lower price than most sit-down restaurants.

“They sell a lot of burritos, they have a lot of stores,” Canham-Clyne said. “They can survive a bit of a downturn and continue to grow.”

Business

Video: How ICE Is Pushing Tech Companies to Identify Protesters

new video loaded: How ICE Is Pushing Tech Companies to Identify Protesters

By Sheera Frenkel, Christina Thornell, Valentina Caval, Thomas Vollkommer, Jon Hazell and June Kim

February 14, 2026

-

Alabama1 week ago

Alabama1 week agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoVideo: Farewell, Pocket Books

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoApple might let you use ChatGPT from CarPlay

-

Illinois6 days ago

Illinois6 days ago2026 IHSA Illinois Wrestling State Finals Schedule And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHegseth says US strikes force some cartel leaders to halt drug operations

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘Regime change in Iran should come from within,’ former Israel PM says

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoWith Love Movie Review: A romcom with likeable leads and plenty of charm

-

News1 week ago

Hate them or not, Patriots fans want the glory back in Super Bowl LX