Business

Movie theaters make plea for more films, rail against piracy at CinemaCon 2024

Somehow, heartbreak feels good in a place like CinemaCon — where no matter how many hits the motion picture industry has taken over the last year (and, uh, it’s taken a lot), exhibitors from all over the world unfailingly come together to exude enthusiasm about the moviegoing experience and optimism about the future of cinema.

Flag bearers for the Motion Picture Assn., the National Assn. of Theatre Owners and other major industry players convened Tuesday at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas to deliver their annual state-of-the-business address and officially kick off the event. Movie stars, filmmakers and studio heads are expected to tease, extol and in some cases screen their upcoming releases.

There’s a lot riding on those movies in the wake of a box office slump partially brought on by the Hollywood writers’ and actors’ strikes, which delayed several movies and effectively halted film and TV production last year for about six months.

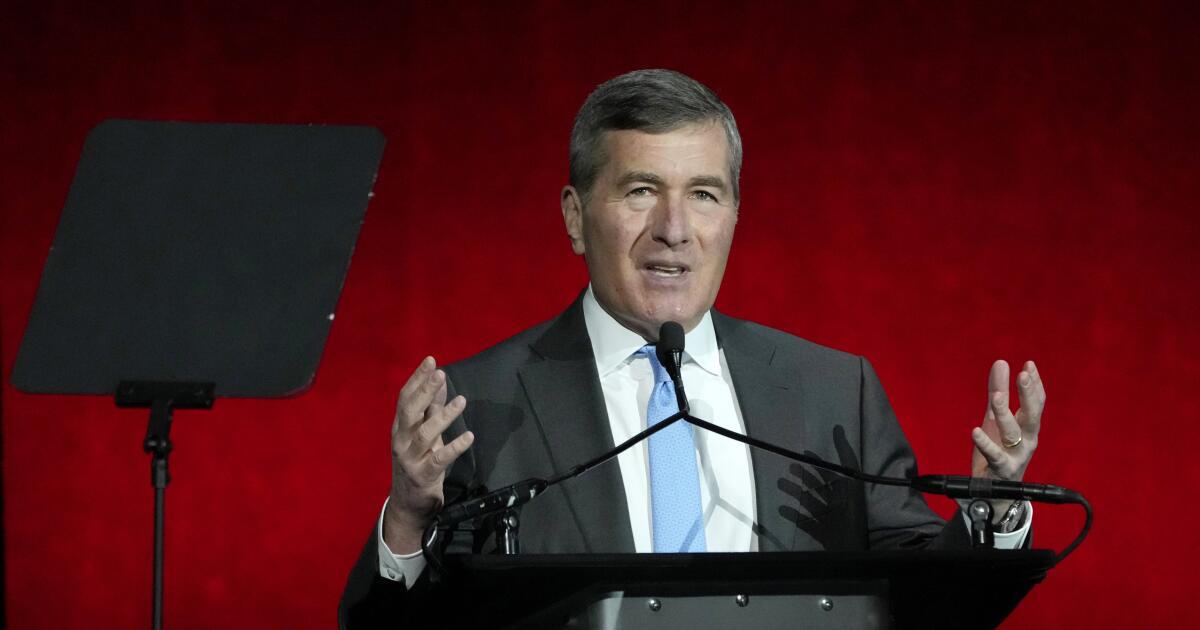

“We can’t shy away from the stark challenges of this moment, nor can we ignore this time of volatility in our industry,” said Charles Rivkin, chief executive of the MPA, during Tuesday’s presentation. Washington-based MPA represents the Hollywood studios, including Disney and Netflix.

“Yet no one should fear that uncertainty,” he added, “because after all, we work in a business where unexpected twists can make for an epic story. … We understand the stakes. We recognize the need to do everything possible to ensure the enduring health of cinema.”

Global box office revenue is predicted to hit $32 billion in 2024, according to film analytics firm Gower Street, which is nowhere near the $40-billion-plus heights of the pre-COVID-19 era. But since the beginning of 2024 — when domestic box office revenue was down 20% from the previous year — some glimmers of hope have emerged.

In March, the highly anticipated sequel to Warner Bros.’ “Dune” launched at $82.5 million in the United States and Canada — the first true blockbuster opening weekend since AMC Theatres’ “Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour” ($93.2 million).

Following the desperately needed success of “Dune: Part Two” — which has now grossed more than $255 million domestically — Universal Pictures’ “Kung Fu Panda 4” notched a solid $58-million domestic debut, Sony Pictures’ “Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire” posted a decent $45 million and Warner Bros.’ “Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire” drew an impressive $80-million bow.

Exhibitors on Tuesday also touted the rising popularity of Japanese cinema in the United States, including Crunchyroll-distributed anime hits such as the latest “Demon Slayer” movie and Toho Co.‘s Oscar-winning “Godzilla Minus One.”

Mitchel Berger, senior vice president of global commerce at Crunchyroll, said Tuesday that the global anime business generated $14 billion a decade ago and is projected to generate $37 billion next year.

“Anime is red hot right now,” Berger said.

“Fans have known about it for years, but now everyone else is catching up and recognizing that it’s a cultural, economic force to be reckoned with.”

Exhibitors are hoping that momentum holds despite also weathering several recent box office disappointments, such as Universal Pictures’ misbegotten spy thriller “Argylle” and Sony Pictures’ superhero disaster “Madame Web.”

When the actors’ strike concluded in November, theater operators expressed concerns about the health of the 2024 film slate. The overlapping work stoppages prompted studios to push at least a dozen movies to 2025 from 2024, including the eighth installment in Paramount Pictures’ “Mission: Impossible” saga and Disney’s live-action remake of “Snow White.”

Cinemark Chief Executive Sean Gamble estimated in February that 95 pictures were slated to open this year in wide release, as opposed to 110 in 2023. And nothing spells danger for exhibitors like a thinned-out release schedule. It doesn’t help that the average length of the theatrical window significantly shrank (from 90 days to roughly 35 to 40 days) after the COVID-19 pandemic shut down movie theaters for more than a year.

At Tuesday’s presentation, exhibitors pleaded with distributors to take a leap of faith and commit to releasing movies in cinemas year-round — not just during times that have historically seen heavier foot traffic.

“For my friends in distribution, please embrace digital’s flexibility and offer your awe-inspiring movies 52 weeks of the year to every exhibitor,” said Chris Johnson, CEO of Classic Cinemas. “Eliminate print counts and trust us to make programming and scheduling decisions that yield the best results for all. … If you have a hit, we will hold it.”

Michael O’Leary, CEO of the National Assn. of Theatre Owners, also made the case for more small- and medium-budget releases that attract cinephiles, citing prestige titles such as A24’s “Past Lives” and Amazon MGM Studios’ “American Fiction.”

“It’s not enough for us to simply sit back and want more movies,” O’Leary said. “We must work with distribution to get more movies of all sizes to the marketplace.”

This year, a number of potential upcoming blockbusters remain.

Universal is cooking up “Twisters,” “Wicked” and “Despicable Me 4”; Warner Bros. is sitting on “Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga,” “Joker: Folie à Deux” and “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice”; Paramount is distributing “Gladiator 2” and “A Quiet Place: Day One”; Sony is launching “Venom: The Last Dance”; Disney is set to release “Inside Out 2,” “Moana 2” and “Deadpool & Wolverine”; and Amazon MGM Studios is about to drop “Challengers,” starring Zendaya.

The last few years at CinemaCon have drawn battle lines between exhibitors and streamers. During the streaming wars of 2021 and 2022, studios threw an excessive amount of resources and funds at streaming projects in an effort to compete with Netflix.

At the time, streaming was painted as theaters’ archnemesis. But the great streaming boom of the early 2020s has subsided as entertainment companies — reeling from financial losses — are tightening their belts and greenlighting less streaming content.

In December, Disney unveiled plans to re-release three Pixar titles — “Soul,” “Turning Red” and “Luca” — in theaters this year after initially routing them directly to streaming. Additionally, “Moana 2” — originally conceived as a TV series to be streamed on Disney+ — was reworked into a feature coming to the big screen in November.

Though streaming undoubtedly still poses a threat to movie theaters, the tides appear to be turning ever so slightly in exhibitors’ favor as studios rethink their release strategies and film fanatics continue to splurge on Imax and other premium large formats.

“You can watch a movie on TV or on your tablet or on your computer, but you experience it in a theater,” O’Leary said. “And part of what makes the movie so special is the theaters themselves.”

However, exhibitors at CinemaCon did repeatedly express concerns about the rise of illegal streaming and digital piracy. Rivkin condemned the practice as “insidious forms of theft” that harm production workers, actors, directors, writers, craftspeople and even consumers who risk falling prey to malware viruses when watching movies illegally online.

Rivkin estimated that on average, piracy costs the movie theater industry more than $1 billion per year. During his state-of-the-industry address, he called on Congress to enact site-blocking legislation that would prevent internet users in the United States from accessing websites that stream films illegally.

“Piracy operations have only grown more nimble, more advanced and more elusive every day,” Rivkin said. “These activities are nefarious by any definition. They’re detrimental to our industry by any standard. And they’re dangerous for the rights of creators and consumers by any measure.”

Business

Gov. Newsom seeks faster review of insurance rate hikes. What to know

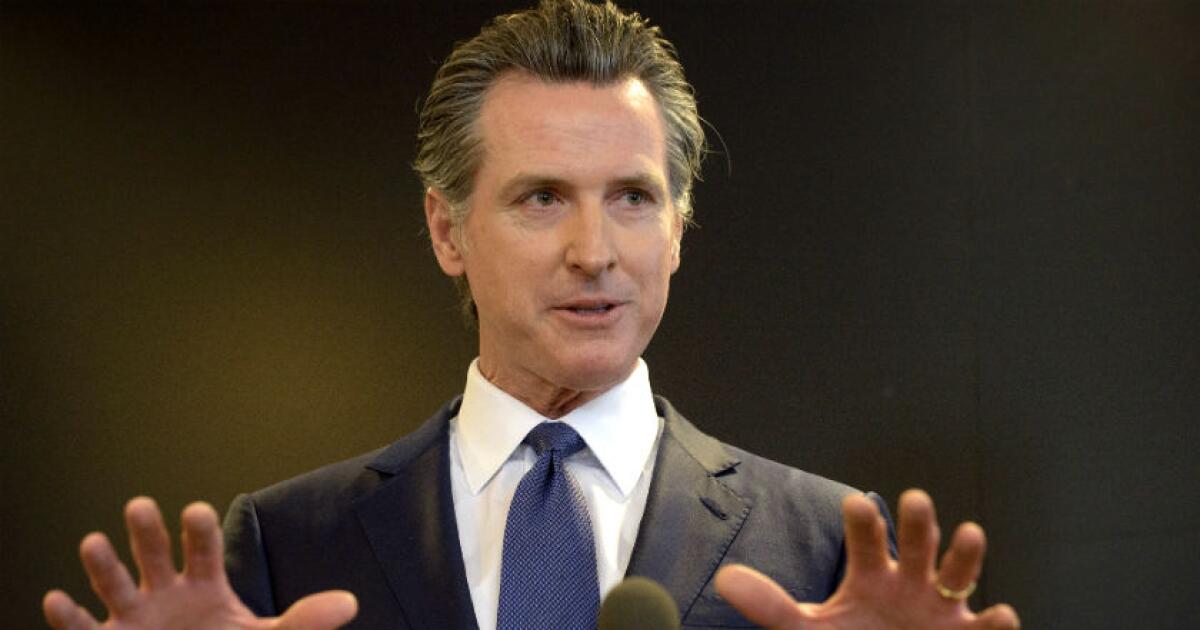

With insurers continuing to pull back from the California’s homeowners’ market, Gov. Gavin Newsom wants to speed up the process by which the companies have their requests for rate hikes reviewed.

The governor said Friday that he is backing a bill that would require the Department of Insurance to complete reviews of proposed premium increases within 60 days to halt any more exits from the market. Here’s what to know:

What exactly did the governor say?

Newsom said that immediate steps need to be taken to stabilize the market, which has seen insurers not renew existing policyholders, stop writing new policies or pull out of the market entirely — sending many homeowners to the insurer of last resort, the state’s FAIR Plan, which is now on the hook for more than $300 billion in payouts. Newsom said he was “deeply mindful” of the burdens placed on the plan.

The governor said he had considered issuing an executive order, but instead is proposing a bill that would require the Insurance Department to speed up its review process of premium rate-hike requests.

“We need to stabilize this market. We need to send the right signals. We need to move,” he said.

Isn’t there already an insurance reform package being hashed out in Sacramento?

Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara is holding hearings on his Sustainable Insurance Strategy, a set of comprehensive regulations intended to stabilize rates and make it more attractive for insurers to write homeowners policies, especially in wildfire areas such as hillsides and canyons.

However, these regulations won’t become law until the end of the year — a deadline sought by the governor, assuming it can be met.

“It should not take this long for emergency regulations,” Newsom said. “We can’t wait until December.”

How would this bill fit into the larger set of reforms?

Lara has reached a grand bargain with the insurance industry to make the market more attractive, though details are still being worked out.

The plan would allow insurers to include the cost of reinsurance they buy to protect themselves from large fires and other catastrophes into premium costs. It also would allow them to set rates using sophisticated algorithms to predict the risk and cost of future fires, rather than just base them on past events. It’s unclear how an insurer’s application for an expedited rate approval this year would fit into the proposed reforms.

Has Lara reacted to the governor’s proposal?

The commissioner tweeted Friday that his department has taken “significant steps forward” to implement his planned reforms but more needs to be done — and that his department is working with the governor and the Legislature “on critical budget language that keeps us on track to get the job done.”

What do consumer groups have to say?

Jamie Court, president of Consumer Watchdog, said he didn’t understand the proposal, worrying that it would be a “rubber stamp” on proposed rate increases.

He noted that Proposition 103, the landmark 1988 initiative that gives the insurance commissioner authority to review rate hikes, already mandates that they are conducted within 60 days except in certain circumstances. Those circumstances include requests for rate increases exceeding 7% for homeowners insurance, which allow consumers to seek a hearing, or the commissioner’s own decision to conduct a hearing.

What is the insurance industry’s reaction

Rex Frazier, president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, a trade group of property and casualty insurers, said despite the promise of 60-day rate reviews under Proposition 103, they are taking longer. He said the Insurance Department will often request that insurers waive their rights to a speedy decision or face an administrative hearing, which can lead to extensive delays. However, Frazier withheld comment on the governor’s proposal until the draft language is released.

What are the next steps?

Newsom’s office will release the draft bill, which will be carried by a member of the Legislature and be included in the process for adopting the state budget, which the Legislature must approve by June 15. Newsom made his remarks Friday in outlining plans for a revised $288-billion budget, which calls for a series of cutbacks to close a nearly $45-billion shortfall.

Business

The Battle for The Streets of New York

On a recent morning, the intersection of East 77th Street and Lexington Avenue presented a vivid illustration of the tumult.

A taxi trying to make a left turn had to maneuver around a Verizon crew digging up the asphalt. A box truck was parked in the bus lane, and the M102 bus, with its accordionlike belly, was forced to change lanes and snake around it.

Dozens of people streamed out of the subway and into the crosswalk. A man pushing a double stroller navigated between the subway entrance and a sidewalk compost box. A woman’s shopping cart wheels got stuck in a crack in the sidewalk. CitiBikes and delivery bikes whizzed by. A cargo bike stopped in front of a FedEx truck that was unloading packages next to a bike lane.

Lively, energetic streets make city living attractive — people to watch, windows to browse, benches to sit on, trees for shade.

But lately, New York City streets are teetering between lively and unlivable. Residents clash over traffic, noise, parking, 5G towers and heaps of trash. Most years, far fewer pedestrians get killed by motorists than in generations past, but last year was the deadliest year for cyclists since 1999.

Still, people who have thought deeply about the state of the city’s streets believe dramatic improvement may be on the way — if New York is willing to seize the moment.

That’s because the city is about to embark on the nation’s first congestion pricing plan, charging most drivers $15 to enter much of Manhattan below 60th Street — and forcing many commuters to find a different way into the city.

The aim is to reduce car traffic in one of the world’s busiest commercial districts and raise money for public transportation.

People, bikes and vehicles compete for space on New York City’s streets.

Karsten Moran for The New York Times

“I think this could be the catalyst for a streets renaissance in New York,” Janette Sadik-Khan, New York City’s former transportation commissioner, said in a recent interview.

“We have to talk about how we’re going to reclaim that space and make it work for people.”

Of course, congestion pricing, too, comes with a fight. The plan is supposed to start in June, but it faces several lawsuits brought by elected officials and residents from across the region, who describe it as ill-conceived and unfair to commuters who drive because public transit isn’t robust enough to serve their needs.

“They don’t drive because they want to,” said Susan Lee, a member of a coalition called New Yorkers Against Congestion Pricing. “They don’t want to sit in traffic.”

Could congestion pricing actually reduce the number of cars in the city to a dramatic extent? If so, what would take their place?

There are other ideas and experiments in the works for taming New York’s streets, and they raise questions of their own. Could a proposal to ban parking close to intersections improve public safety? Will the Sanitation Department’s garbage containerization plan make sidewalks cleaner? Is there a way to keep package delivery trucks from blocking the streets? Must 5G technology create public eyesores in residential neighborhoods?

In the months ahead, The New York Times will examine the debates raging in neighborhoods all over the city about who and what gets to take up space on New York’s streets and sidewalks.

How did we get here?

Orchestrating the flow of traffic and pedestrians has been a complicated and emotional project for centuries.

New York City’s streets were laid out before anyone knew how they would ultimately be used — long before cars were even invented. The first city planners could not have anticipated Uber vehicles, let alone Amazon deliveries or commuters on electric scooters.

In New York’s earliest days, the streets were a free-for-all. People walked or rode horses. There were no crosswalks or stoplights; if you had to cross the street, you simply walked across the street.

Traffic on Broadway in 1859 consisted of pedestrians, horse-drawn carts and streetcars.

William Notman, via Getty Images

Soon, horse-drawn vehicles used the streets alongside pedestrians, and people dashed between them. (Later, New Yorkers dodged streetcars in much the same way, giving the Brooklyn baseball team its name.)

The arrival of bicycles neatly encapsulated the city’s ever-shifting debate over how the streets should be used — and by whom.

By the 1890s, the streets were full of bikes. Men and women took to cycling through the city so quickly — and dangerously — that it was called “scorching.”

About 100 years later, in 1987, speeding bike messengers were deemed so dangerous that bicycles were banned from Midtown — temporarily.

Today, the city encourages residents and visitors to ride bikes. New York has bike lanes and a flourishing bike share program, plus an explosion of food delivery powered by e-bikes. The renewed popularity has also come at a grave cost: Last year 30 cyclists were killed on city streets, and 395 were severely injured.

“It’s hard to say whether it’s the best of times or the worst of times for bicycling,” said Jon Orcutt, the director of advocacy at Bike New York and the former policy director at the city’s Department of Transportation. “More people are doing it than ever.”

“If you’re not killed — squished like a bug — you can bike across town in 10 minutes,” he added. “It’s easy. It’s really efficient.”

Enter the car — and the car crash

On the evening of Sept. 13, 1899, Henry Hale Bliss, a 69-year-old real estate broker, was riding a Manhattan streetcar on his commute home.

At 74th Street and Central Park West, Mr. Bliss stepped from the streetcar and into the street, where he was immediately hit by a taxi. He died on the scene and is recognized as the first person in the United States to be killed by a car. There is a plaque at the intersection commemorating his death.

“At the end of the Gilded Age, right before World War I, suddenly, there were motor vehicles everywhere,” said James Nevius, an author and New York historian.

The development meant people could move around faster — but it also put more people in danger.

In 1920, there were about 200,000 registered vehicles in New York City; by 1925 that number had more than doubled. A century later, that figure is two million.

This scene of Park Avenue near 57th Street was typical of 1930s traffic. Over 10 million cars went through the Holland tunnel in 1930.

George Rinhart/Corbis, via Getty Images

And yet New Yorkers are still using the same streets that were laid out generations ago. In Manhattan, the rigid street grid was designed in 1811. Avenues are 100 feet across. Cross streets are 60 feet wide, including the space for sidewalks on both sides.

That’s 720 inches in which to fit not just cars but also pedestrians, baby strollers, trash, compost, scaffolding, bicycles, e-bikes, scooters, skateboards, package delivery trolleys, garbage trucks, delivery trucks, food carts, 5G towers, dining sheds, trees, CitiBike docks, buses, taxis, ambulances and on-street parking.

It’s like a giant game of Tetris — except all the pieces just won’t fit.

In fact, some of the pieces are growing larger: In the past decade, the average vehicle got 12 percent longer and 17 percent wider. (Cars’ blind spots have also gotten larger.)

And the number of pieces just keeps expanding. New York City’s population reached 8.8 million in 2020, and the New York region is now home to nearly 19 million people. The city’s population has dropped some in the past few years, but city officials believe that recent population estimates have significantly underestimated the number of newly arrived migrants, which, by some counts, is over 180,000.

Taming the streets

Even as New York’s streets and sidewalks have become more chaotic, there are also plenty of examples of the opposite: moments when the city has tamed the traffic and found new uses for its old spaces.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, sweeping pedestrian plaza initiatives — detouring cars and encouraging space for sitting and strolling — have gradually changed the landscape, from the Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens to Times Square.

Times Square was once full of traffic. In May 2009, the city closed Broadway to cars and set out lawn chairs, the start of the area’s transformation to pedestrian plaza.

Damon Winter/The New York Times

The Open Streets program restored pedestrian-first streets, free of cars and safe enough for strolling, chatting and letting kids ride bikes.

The coronavirus pandemic ushered in a chance to rethink public spaces, and the absolute quiet on the streets during lockdown was a reminder that the city isn’t inherently noisy, but traffic is.

And there are plenty of other places to look for inspiration: In Bogotá, Stockholm, London and Paris, certain streets are being closed to cars. There is an effort in Europe to avoid the oversize pickup trucks and SUVs that make American roads so deadly. Paris has designated “school streets” where cars have been removed to make way for children. Cycling is flourishing in Europe; emissions are down.

In New York, Ms. Sadik-Khan, the former transportation commissioner, is among the people thinking deeply about the future of streets — and she is optimistic.

“There’s a new generation of New Yorkers who’ve never known a city without protected bike lanes and bike share,” Ms. Sadik-Khan said. “More people than ever are working from home. Commuting patterns are in flux. There’s the opportunity to make a new deal for people getting around.”

What will a “new deal” look like? And will New Yorkers be on board?

No matter what happens, change doesn’t come without a fight — and many of the battles will be fought street by street and block by block.

Over the next few months, we will take a close look at some of these street fights — and we’re eager to hear about yours, too.

Use this form to tell us what you think about the state of New York City’s streets.

Business

L.A. influencers, businesses live or die on TikTok's algorithm. Now they fear for the future

Brandon Hurst has built a loyal social media following and a growing business selling plants on TikTok, where a mysterious algorithm combined with the right content can let users amass thousands of followers.

Hurst, who’s based in the San Fernando Valley, sold 20,000 plants in three years while running his business on Instagram. After expanding the business he launched in 2020 to TikTok Shop, an e-commerce platform integrated into the popular social media app, he sold 57,000 plants in 2023.

He now conducts business entirely on TikTok and relies on its sales as his sole source of income. Hurst, 30, declined to say how much he makes.

Hurst also posts content about plant care for a 186,000-person following on TikTok. He’s one of thousands of content creators who engage with an audience on the app and make money doing it — whether by selling products or partnering with brands.

But Hurst, along with many other creators and influencers, is now wondering whether Washington could threaten the progress he’s made with his business.

After President Biden signed a bill into law that would ban the Chinese-owned app in the U.S. unless it is sold to an American company, social media experts said the economic effects would extend beyond individual creators such as Hurst.

TikTok has advantages that set it apart from other platforms such as Instagram and Snapchat, Hurst and other creators said.

“What makes TikTok special is the algorithm,” Hurst said, noting that if TikTok’s owners sell the app, the algorithm could change.

As with other social networks, TikTok uses a secret algorithm to determine which videos to show to each user, based on what they’ve seen before and with whom they have interacted. What sets it apart is the videos are usually short, informal and designed to entertain, and many spark conversations among creators.

Many small businesses prefer TikTok because of its informality — they don’t need a big production budget to showcase their products or services. They just need a good hook to grab viewers, and once they’ve gone viral a time or two and established their niche, TikTok will bring the viewers to them.

A ban on TikTok would have cascading effects — especially in Los Angeles, where so many influencers live and work. The Hollywood apartment complex 1600 Vine, for example, is considered by many to be a headquarters for content creators.

That address isn’t the only hub for TikTok stars. Another group lives in a Beverly Hills home dubbed the Clubhouse. If TikTok is banned in the U.S., many creators would lose large portions of their business, they said.

But a sale doesn’t solve every problem either. Some players are already lining up to buy the app even though it’s not yet for sale. And creators such as the Clubhouse residents, who make content as their full-time job, fear a new TikTok ownership could make it harder to attract an audience.

Any ban is expected to face legal challenges and delays, and TikTok executives have said there will be no immediate effect on the app.

Roughly 7 million small-business owners and 1 million influencers rely on TikTok for their livelihoods, according to Rory Cutaia, chief executive of Verb Technology, which owns a livestream social media shopping platform that has partnered with TikTok Shop.

The platform Market.Live helps small-business owners launch on TikTok, where they also often post videos about their products. TikTok Shop receives around 6,000 applications from small businesses each day, Cutaia said.

Banning TikTok would send ripple effects through the economy because it’s become a primary platform for emerging companies, he said.

“You’re probably talking about billions of dollars that would be removed from the economy,” Cutaia said. “The entire world of retail has changed completely. Today, you need to be distributing your products through social media.”

People calling for the banning of TikTok attend a news conference at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., on March 23, 2023.

(J. Scott Applewhite / Associated Press)

Adam Sommers, who owns Willow Boutique in Cincinnati, Ohio, with Chelsea Sommers, said TikTok leveled the playing field for small businesses. His was one of the first to sell merchandise on TikTok Shop.

“Everybody had an opportunity to become the next giant in their industry,” Sommers said. “A lot of people have scaled probably beyond their wildest dreams.”

Influencers don’t need to own a business to make money on TikTok, one creator said. They also don’t need to have huge followings to make significant profits, according to Denise Butler, chief operating officer at Verb Technology.

“TikTok very uniquely sets up a content creator to build community and provides amazing exposure,” said Payton Reed, a lifestyle blogger based in Memphis, Tenn., with around 16,000 followers. “When I first started blogging and creating content, I didn’t realize that it could eventually turn into a career.”

Reed makes money sharing links to other products. She was able to help support her husband financially through medical school with her content creator income, she said.

For small-business owners, TikTok Shop makes it “frictionless” to sell and buy products on the app, Butler said. Users can shop while watching a relevant video, interact with others who have purchased the product and complete the purchase without leaving the app.

Although some say TikTok is superior to other platforms for its e-commerce functionality, not everyone relies solely on the app.

Adam Waheed, a sketch-comedy content creator based in Los Angeles, said it’s important to have income from more than one platform. He made around $11 million last year across his social media platforms, including Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and Facebook.

“We’ve worked so hard to build these platforms,” Waheed said. “I think for certain creators who rely more on TikTok, it’s going to be much more of an issue,” he said of the potential ban.

TikTok users in L.A. include small-business owners, content creators and everyday users who can engage with millions of personalities and products. The app is its own local economy, and a ban would leave a gaping hole, creators said.

According to a study from TikTok and Oxford Economics, 890,000 businesses and 16 million people actively use TikTok in California. Forty percent of small to midsize businesses in the state said TikTok was crucial to their business.

TikTok also released national economic data showing the app drove $15 billion in revenue for small businesses.

“More than half of small-business owners say TikTok allows them to connect with customers they can’t reach anywhere else,” the report said.

Content creators and the companies that work with them aren’t the only ones concerned about a potential TikTok ban. Sen. Laphonza Butler (D-Calif.) recently wrote a letter to Biden urging him to consider how a ban would affect laborers.

“Approximately 8,000 people work for TikTok in the United States, concentrated in California and New York,” the letter said. “Their employment and the livelihoods of their families hang in the balance.”

The senator said a ban would harm small-business owners, contractors and other workers, including janitors and servers who help businesses run.

“We need to be taking the time to consider the broader economic impacts,” she said in an interview with The Times. “There are thousands of workers who I think are not being considered.”

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAustralian lawmakers send letter urging Biden to drop case against Julian Assange on World Press Freedom Day

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBrussels, my love? Champage cracked open to celebrate the Big Bang

-

News1 week ago

A group of Republicans has united to defend the legitimacy of US elections and those who run them

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Dems seeking re-election seemingly reverse course, call on Biden to 'bring order to the southern border'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘It’s going to be worse’: Brazil braces for more pain amid record flooding

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Stop the invasion': Migrant flights in battleground state ignite bipartisan backlash from lawmakers

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoGerman socialist candidate attacked before EU elections

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpain and Argentina trade jibes in row before visit by President Milei