Business

Hollywood's stunt-driving industry is dominated by men. These women are fighting for change

Four months after her father died in June 2019, Olivia Summers showed up to an introductory meeting at a production company in Santa Monica.

While discussing her extensive work as a stunt driver on numerous car commercials, one of the producers remarked that he was not aware there were women in the stunt-driving industry.

“We just put a guy in a wig,” Summers recalled the producer saying.

Summers, who had fought hard over the past 15 years to make a name for herself in an overwhelmingly male-dominated field, was devastated. Not only did this producer openly admit to “wigging” — a union-prohibited, gender-discriminatory practice where a male stunt performer wears a wig to double for an actress — he acted as if he didn’t even know that drivers like her existed.

Hurt and discouraged, Summers returned to her truck, put the key in the ignition and turned to her biggest supporter — her late father — for guidance. As the engine revved, Summers — who was raised Catholic and makes a sign of the cross before performing stunts — heard her father’s voice.

“He just said, ‘Start an all-female stunt-driving team,’” Summers told The Times. “And that’s how it came about.”

Summers in 2020 founded the Assn. of Women Drivers, billed as “the first and only all female stunt … and performance driving team” in Hollywood. Historically, stunt-driving teams recruited as a unit for commercials, films and/or TV shows have been led by and composed of mostly men.

The goal of the Assn. of Women Drivers, which Summers of Playa Vista runs alongside fellow stunt performer Dee Bryant of View Park-Windsor Hills, is to increase visibility and employment opportunities for female stunt workers.

The Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists — which represents all stunt performers — has collected gender information from 4,636 stunt workers in the union. About 22% (1,025) identified as female, according to a source close to the labor organization who was not authorized to comment.

Summers doesn’t hide her frustration at the boys’ club culture of the stunt-driving industry.

“It’s bulls— because a lot of the guys on the team don’t even like each other,” she said. “They’re just trying to keep it that way so none of the work goes to us or any other independent driver out there. It’s super shady. It’s dark.”

Dee Bryant, left, and Olivia Summers smoke the tires of Summers’ Dodge Challenger in Marina del Rey.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Stunt performers of all genders have been striving to get more respect from the industry. They’ve been in the spotlight recently after the Academy of Motion Pictures unveiled a new Oscars category for casting, perceived as a snub to the stunt community, which has long pushed for Academy Awards recognition to no avail.

The lack of appreciation is particularly galling to stunt workers, who risk their safety to make more famous actors look good. Despite strict on-set rules to prevent accidents, stunt performing remains dangerous work, by definition.

Due to the entertainment industry’s reliance on stunning action set pieces, demand for stunt performers’ services remains significant, despite the rise of computer-generated graphics, the looming threat of AI and the occasional stars performing their own death-defying feats.

Combined, Summers and Bryant boast hundreds of credits on commercials, films and TV series, including “CSI,” “9-1-1,” “Bridesmaids” and “L.A.’s Finest.” While executing complex crash and high-speed chase sequences, Summers has doubled for actors such as Sarah Paulson, Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Ming-Na Wen ; while Bryant has subbed in for Angela Bassett, Regina King and Kerry Washington.

Viewers might have seen Summers weaving through oncoming traffic in an apocalyptic frenzy while doubling for Paulson in the Netflix thriller “Birdbox”; or Bryant zooming through the crowded streets of Hollywood on a motorcycle while doubling for Gabrielle Union during a police pursuit in the pilot episode of “L.A.’s Finest.”

“What dawned on me was the fact that this would create visibility for women and no longer give stunt coordinators, producers, ad agencies … the excuse to wig a male,” Bryant said. “I thought that this would be exactly what we needed to put a stop to that practice.”

Both women were encouraged by their fathers to take up sports such as waterskiing and dirt-biking and learn how to maneuver various types of vehicles from a young age.

Growing up in Toronto, Summers was operating snowmobiles solo by the age of 12. The third child of five, she experienced her fair share of mishaps — flying off the back of her dad’s snowmobile, slicing her hand open in a boating accident, repeatedly trying and failing to stand on water skis until her lips turned blue .

Olivia Summers, left, and Dee Bryant have driven in commercials for various car companies, including Ford.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Meanwhile, Bryant’s father — a Harley guy who belonged to a motorcycle crew — gifted his daughter her first dirt bike at the age of 11. Bryant grew up piloting motorcycles on the sunbaked terrain of California’s San Gabriel Valley.

“My dad bought me a motorcycle, and now I have 13 motorcyles,” Bryant said. “It’s his fault.”

Before long, she set her sights on water sports and eventually the “the big Tonka toys” that rumbled around construction sites.

For now, Bryant and Summers are the only two members of the Assn. of Women Drivers. They do, however, have plans to expand by recruiting drivers specializing in cars, motorcycles, dirt bikes and watercraft.

After catching wind of their efforts, some Hollywood producers at William Morris Endeavor approached Bryant and Summers with a pitch for a reality competition program centered on their search for the most talented women stunt drivers — and asked the duo to hold off on recruiting more members while they shop the idea.

But that hasn’t stopped them from mentoring fellow female stunt drivers looking to carve out space for themselves in the entertainment business. Summers and Bryant said it’s in their best interests to help train aspiring female stunt drivers so that their protégées can lead by example.

“Yesterday I drove two hours to help one of the girls that I’m mentoring buy a stunt car because I want these girls to look good on set,” Bryant said. “It’s a reflection on us if they don’t. Then the coordinator goes, ‘See, there’s no good women drivers.’”

Decatur, Ga.-based stunt driver and motorcyclist Jwaundace Candece — who has worked on “Atlanta,” “WandaVision” and “Baby Driver” — credits Bryant with teaching her how to “ride for the cameras” and pointing her to people who could further her career.

When she was hired by stunt coordinator Darrin Prescott to work on “Baby Driver,” Candece relied on Bryant’s sage advice: “Hold your own, drive like a man and prove them wrong.” Impressed, stunt coordinator Thom Williams tapped Candece for HBO’s “Watchmen.”

Bryant and Summers “are starting something that is innovative and revolutionary,” Candece said. “I hope it’ll open up doors to hire more women, more women of color — more women, period — because that’s what’s needed.”

In addition to wigging, Bryant, Candece and other stunt women of color have had to contend with “paint downs” — or putting white people in brownface or blackface instead of hiring stunt women of color to double for non-white actors. Fewer than 10 years ago, Warner Bros. publicly apologized for casting a white stunt woman to double for a Black guest star in the superhero series “Gotham.”

“I first spoke up against that … maybe 15, 20 years ago, and it’s still happening,” Bryant said. “That’s what happens in this business behind the scenes.”

As onscreen representation for women is shifting and more actresses are being cast in action roles, Hollywood needs to hire more women stunt drivers to double for them.

And it’s not just the stars who require doubles — for every action hero or villain who operates a vehicle onscreen, there are dozens more background drivers populating the streets, called “nondescript drivers.”

It’s especially rare for women stunt performers to get work as nondescript drivers. Bryant estimated that 90% of the time she is tapped for a project, she is in the “hot seat,” doubling for a principal cast member.

“How stupid does it look when you watch the movie, and you’re like, ‘Not one woman cop in 2023?’” Summers said. “When they get out [of their cars], and you just see a bunch of white guys with their guns drawn on the criminal. Come on, that doesn’t look right.”

To address this issue, Bryant called on entertainment companies to employ people to oversee hiring practices in the stunt department and advise the studios to diversify their stunt-driving teams.

The Oscars controversy was just another poke in the eye. After the academy’s recent decision to create a new Oscar for achievement in casting sparked outrage in the stunt community, ABC incorporated a sizzle-reel ode to stunt performers into this year’s Oscars telecast — a move Bryant dismissed as “a joke.”

“I have not watched the Oscars in over 20 years,” Bryant said. “I boycott because I think it’s ridiculous. … We, as stunt performers, are putting our life and limb on the line.”

Business

Gov. Newsom seeks faster review of insurance rate hikes. What to know

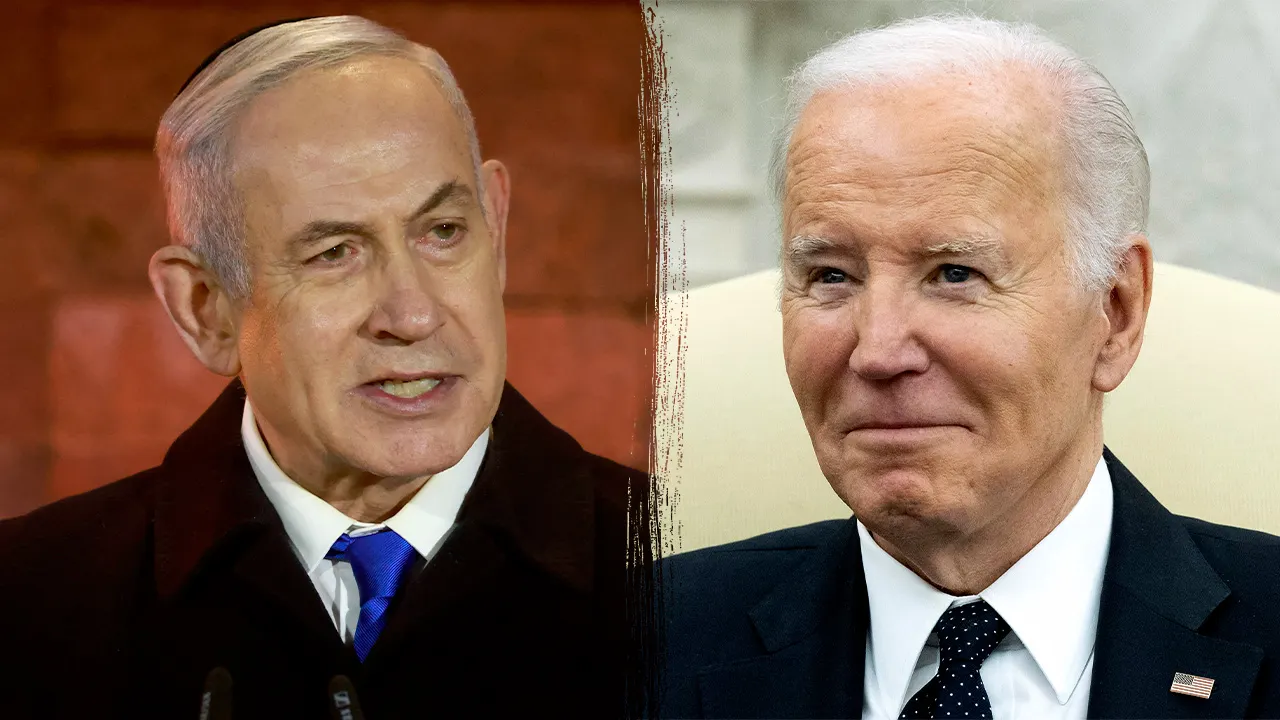

With insurers continuing to pull back from the California’s homeowners’ market, Gov. Gavin Newsom wants to speed up the process by which the companies have their requests for rate hikes reviewed.

The governor said Friday that he is backing a bill that would require the Department of Insurance to complete reviews of proposed premium increases within 60 days to halt any more exits from the market. Here’s what to know:

What exactly did the governor say?

Newsom said that immediate steps need to be taken to stabilize the market, which has seen insurers not renew existing policyholders, stop writing new policies or pull out of the market entirely — sending many homeowners to the insurer of last resort, the state’s FAIR Plan, which is now on the hook for more than $300 billion in payouts. Newsom said he was “deeply mindful” of the burdens placed on the plan.

The governor said he had considered issuing an executive order, but instead is proposing a bill that would require the Insurance Department to speed up its review process of premium rate-hike requests.

“We need to stabilize this market. We need to send the right signals. We need to move,” he said.

Isn’t there already an insurance reform package being hashed out in Sacramento?

Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara is holding hearings on his Sustainable Insurance Strategy, a set of comprehensive regulations intended to stabilize rates and make it more attractive for insurers to write homeowners policies, especially in wildfire areas such as hillsides and canyons.

However, these regulations won’t become law until the end of the year — a deadline sought by the governor, assuming it can be met.

“It should not take this long for emergency regulations,” Newsom said. “We can’t wait until December.”

How would this bill fit into the larger set of reforms?

Lara has reached a grand bargain with the insurance industry to make the market more attractive, though details are still being worked out.

The plan would allow insurers to include the cost of reinsurance they buy to protect themselves from large fires and other catastrophes into premium costs. It also would allow them to set rates using sophisticated algorithms to predict the risk and cost of future fires, rather than just base them on past events. It’s unclear how an insurer’s application for an expedited rate approval this year would fit into the proposed reforms.

Has Lara reacted to the governor’s proposal?

The commissioner tweeted Friday that his department has taken “significant steps forward” to implement his planned reforms but more needs to be done — and that his department is working with the governor and the Legislature “on critical budget language that keeps us on track to get the job done.”

What do consumer groups have to say?

Jamie Court, president of Consumer Watchdog, said he didn’t understand the proposal, worrying that it would be a “rubber stamp” on proposed rate increases.

He noted that Proposition 103, the landmark 1988 initiative that gives the insurance commissioner authority to review rate hikes, already mandates that they are conducted within 60 days except in certain circumstances. Those circumstances include requests for rate increases exceeding 7% for homeowners insurance, which allow consumers to seek a hearing, or the commissioner’s own decision to conduct a hearing.

What is the insurance industry’s reaction

Rex Frazier, president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, a trade group of property and casualty insurers, said despite the promise of 60-day rate reviews under Proposition 103, they are taking longer. He said the Insurance Department will often request that insurers waive their rights to a speedy decision or face an administrative hearing, which can lead to extensive delays. However, Frazier withheld comment on the governor’s proposal until the draft language is released.

What are the next steps?

Newsom’s office will release the draft bill, which will be carried by a member of the Legislature and be included in the process for adopting the state budget, which the Legislature must approve by June 15. Newsom made his remarks Friday in outlining plans for a revised $288-billion budget, which calls for a series of cutbacks to close a nearly $45-billion shortfall.

Business

The Battle for The Streets of New York

On a recent morning, the intersection of East 77th Street and Lexington Avenue presented a vivid illustration of the tumult.

A taxi trying to make a left turn had to maneuver around a Verizon crew digging up the asphalt. A box truck was parked in the bus lane, and the M102 bus, with its accordionlike belly, was forced to change lanes and snake around it.

Dozens of people streamed out of the subway and into the crosswalk. A man pushing a double stroller navigated between the subway entrance and a sidewalk compost box. A woman’s shopping cart wheels got stuck in a crack in the sidewalk. CitiBikes and delivery bikes whizzed by. A cargo bike stopped in front of a FedEx truck that was unloading packages next to a bike lane.

Lively, energetic streets make city living attractive — people to watch, windows to browse, benches to sit on, trees for shade.

But lately, New York City streets are teetering between lively and unlivable. Residents clash over traffic, noise, parking, 5G towers and heaps of trash. Most years, far fewer pedestrians get killed by motorists than in generations past, but last year was the deadliest year for cyclists since 1999.

Still, people who have thought deeply about the state of the city’s streets believe dramatic improvement may be on the way — if New York is willing to seize the moment.

That’s because the city is about to embark on the nation’s first congestion pricing plan, charging most drivers $15 to enter much of Manhattan below 60th Street — and forcing many commuters to find a different way into the city.

The aim is to reduce car traffic in one of the world’s busiest commercial districts and raise money for public transportation.

People, bikes and vehicles compete for space on New York City’s streets.

Karsten Moran for The New York Times

“I think this could be the catalyst for a streets renaissance in New York,” Janette Sadik-Khan, New York City’s former transportation commissioner, said in a recent interview.

“We have to talk about how we’re going to reclaim that space and make it work for people.”

Of course, congestion pricing, too, comes with a fight. The plan is supposed to start in June, but it faces several lawsuits brought by elected officials and residents from across the region, who describe it as ill-conceived and unfair to commuters who drive because public transit isn’t robust enough to serve their needs.

“They don’t drive because they want to,” said Susan Lee, a member of a coalition called New Yorkers Against Congestion Pricing. “They don’t want to sit in traffic.”

Could congestion pricing actually reduce the number of cars in the city to a dramatic extent? If so, what would take their place?

There are other ideas and experiments in the works for taming New York’s streets, and they raise questions of their own. Could a proposal to ban parking close to intersections improve public safety? Will the Sanitation Department’s garbage containerization plan make sidewalks cleaner? Is there a way to keep package delivery trucks from blocking the streets? Must 5G technology create public eyesores in residential neighborhoods?

In the months ahead, The New York Times will examine the debates raging in neighborhoods all over the city about who and what gets to take up space on New York’s streets and sidewalks.

How did we get here?

Orchestrating the flow of traffic and pedestrians has been a complicated and emotional project for centuries.

New York City’s streets were laid out before anyone knew how they would ultimately be used — long before cars were even invented. The first city planners could not have anticipated Uber vehicles, let alone Amazon deliveries or commuters on electric scooters.

In New York’s earliest days, the streets were a free-for-all. People walked or rode horses. There were no crosswalks or stoplights; if you had to cross the street, you simply walked across the street.

Traffic on Broadway in 1859 consisted of pedestrians, horse-drawn carts and streetcars.

William Notman, via Getty Images

Soon, horse-drawn vehicles used the streets alongside pedestrians, and people dashed between them. (Later, New Yorkers dodged streetcars in much the same way, giving the Brooklyn baseball team its name.)

The arrival of bicycles neatly encapsulated the city’s ever-shifting debate over how the streets should be used — and by whom.

By the 1890s, the streets were full of bikes. Men and women took to cycling through the city so quickly — and dangerously — that it was called “scorching.”

About 100 years later, in 1987, speeding bike messengers were deemed so dangerous that bicycles were banned from Midtown — temporarily.

Today, the city encourages residents and visitors to ride bikes. New York has bike lanes and a flourishing bike share program, plus an explosion of food delivery powered by e-bikes. The renewed popularity has also come at a grave cost: Last year 30 cyclists were killed on city streets, and 395 were severely injured.

“It’s hard to say whether it’s the best of times or the worst of times for bicycling,” said Jon Orcutt, the director of advocacy at Bike New York and the former policy director at the city’s Department of Transportation. “More people are doing it than ever.”

“If you’re not killed — squished like a bug — you can bike across town in 10 minutes,” he added. “It’s easy. It’s really efficient.”

Enter the car — and the car crash

On the evening of Sept. 13, 1899, Henry Hale Bliss, a 69-year-old real estate broker, was riding a Manhattan streetcar on his commute home.

At 74th Street and Central Park West, Mr. Bliss stepped from the streetcar and into the street, where he was immediately hit by a taxi. He died on the scene and is recognized as the first person in the United States to be killed by a car. There is a plaque at the intersection commemorating his death.

“At the end of the Gilded Age, right before World War I, suddenly, there were motor vehicles everywhere,” said James Nevius, an author and New York historian.

The development meant people could move around faster — but it also put more people in danger.

In 1920, there were about 200,000 registered vehicles in New York City; by 1925 that number had more than doubled. A century later, that figure is two million.

This scene of Park Avenue near 57th Street was typical of 1930s traffic. Over 10 million cars went through the Holland tunnel in 1930.

George Rinhart/Corbis, via Getty Images

And yet New Yorkers are still using the same streets that were laid out generations ago. In Manhattan, the rigid street grid was designed in 1811. Avenues are 100 feet across. Cross streets are 60 feet wide, including the space for sidewalks on both sides.

That’s 720 inches in which to fit not just cars but also pedestrians, baby strollers, trash, compost, scaffolding, bicycles, e-bikes, scooters, skateboards, package delivery trolleys, garbage trucks, delivery trucks, food carts, 5G towers, dining sheds, trees, CitiBike docks, buses, taxis, ambulances and on-street parking.

It’s like a giant game of Tetris — except all the pieces just won’t fit.

In fact, some of the pieces are growing larger: In the past decade, the average vehicle got 12 percent longer and 17 percent wider. (Cars’ blind spots have also gotten larger.)

And the number of pieces just keeps expanding. New York City’s population reached 8.8 million in 2020, and the New York region is now home to nearly 19 million people. The city’s population has dropped some in the past few years, but city officials believe that recent population estimates have significantly underestimated the number of newly arrived migrants, which, by some counts, is over 180,000.

Taming the streets

Even as New York’s streets and sidewalks have become more chaotic, there are also plenty of examples of the opposite: moments when the city has tamed the traffic and found new uses for its old spaces.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, sweeping pedestrian plaza initiatives — detouring cars and encouraging space for sitting and strolling — have gradually changed the landscape, from the Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens to Times Square.

Times Square was once full of traffic. In May 2009, the city closed Broadway to cars and set out lawn chairs, the start of the area’s transformation to pedestrian plaza.

Damon Winter/The New York Times

The Open Streets program restored pedestrian-first streets, free of cars and safe enough for strolling, chatting and letting kids ride bikes.

The coronavirus pandemic ushered in a chance to rethink public spaces, and the absolute quiet on the streets during lockdown was a reminder that the city isn’t inherently noisy, but traffic is.

And there are plenty of other places to look for inspiration: In Bogotá, Stockholm, London and Paris, certain streets are being closed to cars. There is an effort in Europe to avoid the oversize pickup trucks and SUVs that make American roads so deadly. Paris has designated “school streets” where cars have been removed to make way for children. Cycling is flourishing in Europe; emissions are down.

In New York, Ms. Sadik-Khan, the former transportation commissioner, is among the people thinking deeply about the future of streets — and she is optimistic.

“There’s a new generation of New Yorkers who’ve never known a city without protected bike lanes and bike share,” Ms. Sadik-Khan said. “More people than ever are working from home. Commuting patterns are in flux. There’s the opportunity to make a new deal for people getting around.”

What will a “new deal” look like? And will New Yorkers be on board?

No matter what happens, change doesn’t come without a fight — and many of the battles will be fought street by street and block by block.

Over the next few months, we will take a close look at some of these street fights — and we’re eager to hear about yours, too.

Use this form to tell us what you think about the state of New York City’s streets.

Business

L.A. influencers, businesses live or die on TikTok's algorithm. Now they fear for the future

Brandon Hurst has built a loyal social media following and a growing business selling plants on TikTok, where a mysterious algorithm combined with the right content can let users amass thousands of followers.

Hurst, who’s based in the San Fernando Valley, sold 20,000 plants in three years while running his business on Instagram. After expanding the business he launched in 2020 to TikTok Shop, an e-commerce platform integrated into the popular social media app, he sold 57,000 plants in 2023.

He now conducts business entirely on TikTok and relies on its sales as his sole source of income. Hurst, 30, declined to say how much he makes.

Hurst also posts content about plant care for a 186,000-person following on TikTok. He’s one of thousands of content creators who engage with an audience on the app and make money doing it — whether by selling products or partnering with brands.

But Hurst, along with many other creators and influencers, is now wondering whether Washington could threaten the progress he’s made with his business.

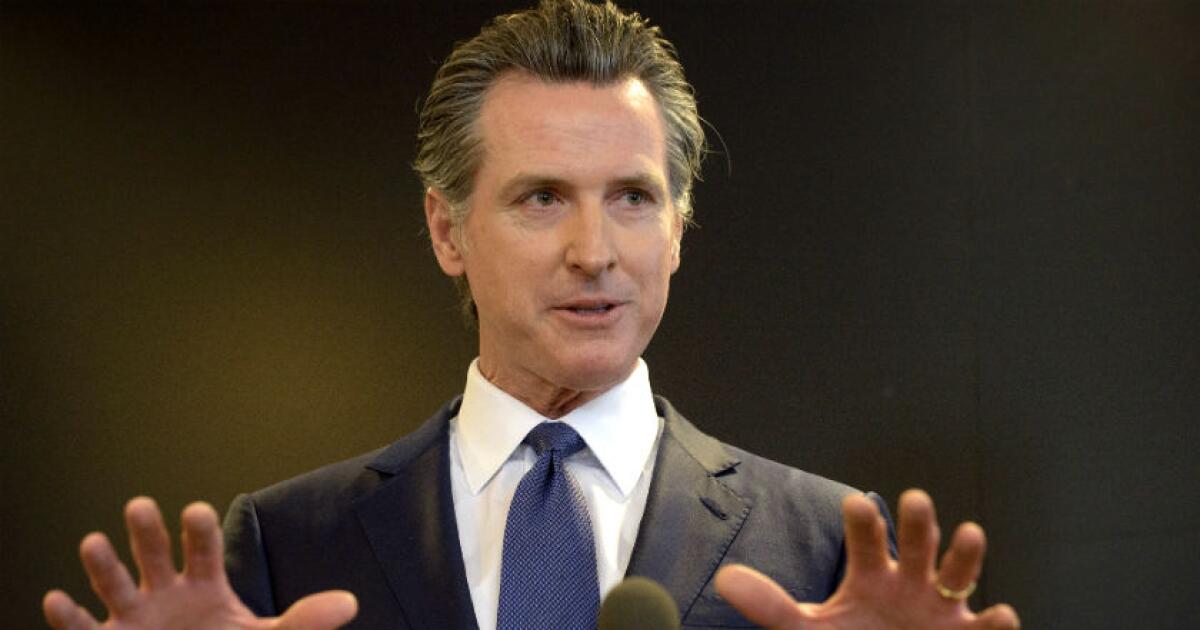

After President Biden signed a bill into law that would ban the Chinese-owned app in the U.S. unless it is sold to an American company, social media experts said the economic effects would extend beyond individual creators such as Hurst.

TikTok has advantages that set it apart from other platforms such as Instagram and Snapchat, Hurst and other creators said.

“What makes TikTok special is the algorithm,” Hurst said, noting that if TikTok’s owners sell the app, the algorithm could change.

As with other social networks, TikTok uses a secret algorithm to determine which videos to show to each user, based on what they’ve seen before and with whom they have interacted. What sets it apart is the videos are usually short, informal and designed to entertain, and many spark conversations among creators.

Many small businesses prefer TikTok because of its informality — they don’t need a big production budget to showcase their products or services. They just need a good hook to grab viewers, and once they’ve gone viral a time or two and established their niche, TikTok will bring the viewers to them.

A ban on TikTok would have cascading effects — especially in Los Angeles, where so many influencers live and work. The Hollywood apartment complex 1600 Vine, for example, is considered by many to be a headquarters for content creators.

That address isn’t the only hub for TikTok stars. Another group lives in a Beverly Hills home dubbed the Clubhouse. If TikTok is banned in the U.S., many creators would lose large portions of their business, they said.

But a sale doesn’t solve every problem either. Some players are already lining up to buy the app even though it’s not yet for sale. And creators such as the Clubhouse residents, who make content as their full-time job, fear a new TikTok ownership could make it harder to attract an audience.

Any ban is expected to face legal challenges and delays, and TikTok executives have said there will be no immediate effect on the app.

Roughly 7 million small-business owners and 1 million influencers rely on TikTok for their livelihoods, according to Rory Cutaia, chief executive of Verb Technology, which owns a livestream social media shopping platform that has partnered with TikTok Shop.

The platform Market.Live helps small-business owners launch on TikTok, where they also often post videos about their products. TikTok Shop receives around 6,000 applications from small businesses each day, Cutaia said.

Banning TikTok would send ripple effects through the economy because it’s become a primary platform for emerging companies, he said.

“You’re probably talking about billions of dollars that would be removed from the economy,” Cutaia said. “The entire world of retail has changed completely. Today, you need to be distributing your products through social media.”

People calling for the banning of TikTok attend a news conference at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., on March 23, 2023.

(J. Scott Applewhite / Associated Press)

Adam Sommers, who owns Willow Boutique in Cincinnati, Ohio, with Chelsea Sommers, said TikTok leveled the playing field for small businesses. His was one of the first to sell merchandise on TikTok Shop.

“Everybody had an opportunity to become the next giant in their industry,” Sommers said. “A lot of people have scaled probably beyond their wildest dreams.”

Influencers don’t need to own a business to make money on TikTok, one creator said. They also don’t need to have huge followings to make significant profits, according to Denise Butler, chief operating officer at Verb Technology.

“TikTok very uniquely sets up a content creator to build community and provides amazing exposure,” said Payton Reed, a lifestyle blogger based in Memphis, Tenn., with around 16,000 followers. “When I first started blogging and creating content, I didn’t realize that it could eventually turn into a career.”

Reed makes money sharing links to other products. She was able to help support her husband financially through medical school with her content creator income, she said.

For small-business owners, TikTok Shop makes it “frictionless” to sell and buy products on the app, Butler said. Users can shop while watching a relevant video, interact with others who have purchased the product and complete the purchase without leaving the app.

Although some say TikTok is superior to other platforms for its e-commerce functionality, not everyone relies solely on the app.

Adam Waheed, a sketch-comedy content creator based in Los Angeles, said it’s important to have income from more than one platform. He made around $11 million last year across his social media platforms, including Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and Facebook.

“We’ve worked so hard to build these platforms,” Waheed said. “I think for certain creators who rely more on TikTok, it’s going to be much more of an issue,” he said of the potential ban.

TikTok users in L.A. include small-business owners, content creators and everyday users who can engage with millions of personalities and products. The app is its own local economy, and a ban would leave a gaping hole, creators said.

According to a study from TikTok and Oxford Economics, 890,000 businesses and 16 million people actively use TikTok in California. Forty percent of small to midsize businesses in the state said TikTok was crucial to their business.

TikTok also released national economic data showing the app drove $15 billion in revenue for small businesses.

“More than half of small-business owners say TikTok allows them to connect with customers they can’t reach anywhere else,” the report said.

Content creators and the companies that work with them aren’t the only ones concerned about a potential TikTok ban. Sen. Laphonza Butler (D-Calif.) recently wrote a letter to Biden urging him to consider how a ban would affect laborers.

“Approximately 8,000 people work for TikTok in the United States, concentrated in California and New York,” the letter said. “Their employment and the livelihoods of their families hang in the balance.”

The senator said a ban would harm small-business owners, contractors and other workers, including janitors and servers who help businesses run.

“We need to be taking the time to consider the broader economic impacts,” she said in an interview with The Times. “There are thousands of workers who I think are not being considered.”

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAustralian lawmakers send letter urging Biden to drop case against Julian Assange on World Press Freedom Day

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBrussels, my love? Champage cracked open to celebrate the Big Bang

-

News1 week ago

A group of Republicans has united to defend the legitimacy of US elections and those who run them

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Dems seeking re-election seemingly reverse course, call on Biden to 'bring order to the southern border'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘It’s going to be worse’: Brazil braces for more pain amid record flooding

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Stop the invasion': Migrant flights in battleground state ignite bipartisan backlash from lawmakers

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoGerman socialist candidate attacked before EU elections

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpain and Argentina trade jibes in row before visit by President Milei