Business

Column: The legal system is closing in on crypto, and things may only get worse

Forget what T.S. Eliot said about April. For the crypto community and its related scamsters, the cruelest month was March.

That month saw a string of jury verdicts and judicial rulings that laid bare the dark underside of cryptocurrency trading, reinforcing its reputation as a haven for fraud and other illegality. The terrain hasn’t proved any more inviting in April thus far, as regulatory investigations and judicial rulings continue to rock the asset class and its promoters back on their heels.

From the standpoint of ordinary investors and the economy as a whole, this is all good. As I’ve written before, the value of crypto tokens, from bitcoin down to the jokiest versions such as dogecoin, is so nebulous that they lend themselves to schemes aimed at separating unwary or gullible investors from their (real) money.

The ‘crypto’ nomenclature may be of recent vintage, but the challenged transactions fall comfortably within the framework that courts have used to identify securities for nearly eighty years.

— U.S. Judge Katherine Polk Failla

The value of cryptocurrencies can be placed anywhere. They don’t produce income like bonds, and their prices can’t be pegged to liquid markets like those of public company securities. To this day, no one has ever explained what cryptocurrencies are useful for, other than paying ransom to crooks holding databases or computer systems hostage.

As recently as Monday, Change Healthcare, a medical transactions processor owned by United Health Group, received a second demand for a ransom payable in crypto tokens only weeks after paying a reported $22-million ransom to rescue personal information, including payment data and medical records for thousands of patients.

That hack of Change’s database disrupted healthcare claims payments nationwide, even forcing some medical providers to lay off workers or shut down entirely for lack of funds.

The new demand apparently came from a ransomware group that feels it has been cheated by its partners in the first demand, who may have absconded with the original payoff. If there’s no honor among thieves, as the adage says, that goes double in crypto. No, not double — squared.

Let’s take a look at crypto’s March Madness before moving on to April.

The highest-profile blow, of course, was the March 28 sentencing of convicted crypto fraudster Sam Bankman-Fried for his conviction in October on seven fraud counts related to the collapse of his FTX crypto exchange.

Federal Judge Lewis Kaplan sentenced Bankman-Fried to a 25-year prison term and ordered him to forfeit more than $11 billion. Kaplan observed that Bankman-Fried had scarcely expressed remorse for his crimes. Kaplan justified the lengthy term by observing from the bench that otherwise Bankman-Fried would “be in a position to do something very bad in the future, and it’s not a trivial risk.”

That’s not all. The day before Bankman-Fried’s sentencing, federal Judge Katherine Polk Failla issued a ruling that may have a more far-reaching effect on the crypto business. Failla cleared the Securities and Exchange Commission to proceed with its lawsuit alleging that the giant crypto broker and exchange Coinbase has been dealing in securities without a license.

What’s important about Failla’s ruling is that she dismissed out of hand Coinbase’s argument, which is that cryptocurrencies are novel assets that don’t fall within the SEC’s jurisdiction — in short, they’re not “securities.”

Crypto promoters have been making the same argument in court and the halls of Congress, where they’re urging that the lawmakers craft an entirely new regulatory structure for crypto — preferably one less rigorous than the existing rules and regulations promulgated by the SEC and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

As it happens, Bankman-Fried made the same pitch in his appearances before congressional committees, back in the day when he was viewed as the last seemingly honest crypto promoter, before it was discovered that he had illegally appropriated his customers’ holdings to fund his and FTX’s own investment ventures.

Failla saw through that argument without breaking a sweat. “The ‘crypto’ nomenclature may be of recent vintage,” she wrote, “but the challenged transactions fall comfortably within the framework that courts have used to identify securities for nearly eighty years.”

Failla also took a swipe at the crypto gang’s amour-propre, rejecting Coinbase’s argument that the case should fall within the “major questions doctrine,” an informal rule that requires regulatory initiatives to be explicitly authorized by Congress if they involve issues of “vast economic and political significance.” Since Congress hasn’t enacted regulations specifically aimed at crypto, Coinbase said, the SEC’s lawsuit should be dismissed.

The judge’s opinion of that argument was withering. “While certainly sizable and important,” she wrote, “the cryptocurrency industry ‘falls far short of being a “portion of the American economy” bearing vast economic and political significance.’”

Crypto simply “cannot compare with those other industries the Supreme Court has found to trigger the major questions doctrine.” Those include the American energy industry and the conventional securities industry itself, she wrote.

Failla’s ruling followed another in New York federal court in which a judge deemed crypto to be securities.

In that case, Judge Edgardo Ramos refused to dismiss SEC charges against Gemini Trust Co., a crypto trading outfit run by Cameron and Tyler Winkelvoss, and the crypto lender Genesis Global Capital.

The SEC charged that a scheme in which Gemini pooled customers’ crypto assets and lent them to Genesis while promising the customers high interest returns is an unregistered security. The SEC case, like that against Coinbase, will proceed.

Both rulings tended to negate a 2023 ruling from federal Judge Analisa Torres of New York in an SEC enforcement action against Ripple, the developer of a crypto token known as XRP. Torres found that under some circumstances the token might not be a security. But her ruling is being buried by an onslaught of decisions by her colleagues that the crypto marketers and exchanges are dealing in unregistered securities, which is illegal.

The hangover from March continued into this month. On April 5, a federal jury in New York found Terraform Labs and its chief executive and major shareholder, Do Kwon, liable in what the SEC termed “a massive crypto fraud.”

The case involved Terraform’s so-called stablecoin UST, a crypto token that was pegged 1 to 1 with the U.S. dollar. Kwon was not in court to hear the verdict; he is in custody in the Balkan country of Montenegro while U.S. and South Korean authorities vie for his extradition.

Terraform had claimed that UST coin would automatically “self-heal” via a software algorithm if its value fell below the $1 peg. That happened in May 2021. When the coin did return to its $1 value, the SEC alleged, Terraform and Kwon bragged that the price restoration was a triumph over the “decision-making of human agents in a time of market volatility.”

In fact, the algorithm had nothing to do with it. According to testimony at the trial, which began in late March, Terraform was secretly bailed out by the trading firm Jump Trading, which may have invested tens of millions of dollars to prop up UST and emerged from the deal with a profit that may have exceeded $1 billion. Failing to disclose that arrangement to investors broke the law, the SEC said.

Kwon and Terraform also lied to the public that Chai, a South Korean financial firm akin to Venmo, was using Terraform to process transactions; in fact, Chai had ceased using Terraform in 2020, the SEC said.

These deceptions, the agency alleged, painted a picture of robust health within Terraform that came apart in May 2022, when UST again depegged from the U.S. dollar and could not be restored. The value of UST fell in effect to zero, the SEC said, “wiping out over $40 billion of total market value … and sending shock waves through the crypto asset community.”

Terraform is now bankrupt; no charges have been brought against Jump.

These events should give American lawmakers pause as they ponder what to do, if anything, about regulating crypto. At a hearing Tuesday of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), the committee chairman, warned that crypto is a potential threat to national security.

“Bad actors — from North Korea to Russia to terrorist groups like Hamas — aren’t turning to crypto because they’ve seen the ads and bought the hype,” Brown said. “They’re using it because they know it’s a workaround. They know that it’s easier to move money in the shadows without safeguards, like know-your-customer rules or suspicious transaction reporting…. We must make sure that crypto platforms play by the same rules as other financial institutions.”

Brown’s words were amplified by Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo, who urged Congress to enact reforms the Treasury has proposed that would strengthen sanctions on “foreign digital asset providers that facilitate illicit finance.”

On Monday, meanwhile, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) — perhaps the most uncompromising foe of crypto on Capitol Hill — took aim at stablecoins by urging the House Financial Services Committee to avoid trying to write rules that would “fold stablecoins deeper into the banking sector.”

Given the potential of stablecoins and their ilk to “undermine consumer protection and the safety and soundness of the banking system,” she warned, any so-called reforms “could amplify and entrench these risks rather than mitigate them.”

What is driving the interest of politicians in promoting an asset class that hasn’t shown any value except where fraud or theft is involved? As is so often the case, it’s money — the green, foldable kind.

Crypto promoters have been stepping up their lobbying in Washington; crypto firms spent nearly $20 million on lobbying in the first nine months of 2023, according to the watchdog group Open Secrets.

As a push for a new regulatory approach, especially among House Republicans, dovetails with an election year, much more spending would appear to be in the offing. It’s a win-win-lose situation, with politicians and crypto promoters poised to win, and ordinary investors as well as the economy as a whole poised to lose.

Business

Red Lobster offered customers all-you-can-eat shrimp. That was a mistake

Red Lobster promised customers an endless supply of shrimp for $20 — a gamble the struggling restaurant chain hoped would help pull it out of its pandemic doldrums.

But Americans, and their appetites, had other plans.

The beloved yet beleaguered pillar of casual dining abruptly shuttered dozens of locations this week, heightening speculation that the chain is careening toward bankruptcy.

Although its dire financial situation isn’t the result of a single misstep, executives at the company that owns a large stake in the chain, as well as industry experts, said that miscalculations over the popularity of the all-you-can-eat shrimp special accelerated the company’s downward spiral.

The closures, including at least five locations in California, were announced in a LinkedIn post Monday by Neal Sherman, the chief executive of a liquidation firm called TAGeX Brands, which is auctioning off surplus restaurant equipment from the shuttered locations.

Representatives for Red Lobster did not respond to a request for comment about the closures, which were listed on its website as temporary, or whether it planned to file for bankruptcy.

But company executives have been vocal about the misguided gamble with shrimp and how they misjudged just how hungry Americans would be for a deal on the crustaceans.

In an effort to boost foot traffic and ease the sales slump that swept through the restaurant industry during the pandemic, Red Lobster executives last year decided to relaunch a popular marketing ploy from years past to lure customers: For $20 they could eat as much shrimp as they wanted.

Eager for a deal during an era of stubbornly high inflation, many consumers eagerly embraced the offer as a challenge. People took to TikTok to brag about how many of the pink morsels they could put down in a single sitting — one woman boasted she’d consumed 108 shrimp over the course of a 4-hour meal.

“In the current environment, consumers are looking to find value and stretch budgets where they can,” said Jim Salera, a research analyst at Stephens, who tracks the restaurant industry. “At $20, it’s very possible for a consumer to eat well past the very thin profit margin.”

During a presentation about sales from the third quarter of last year, Ludovic Garnier, the chief financial officer of Thai Union Group, a seafood conglomerate that has been Red Lobster’s largest shareholder since 2020, cited the endless shrimp deal as a key reason the chain had an operating loss of about $11 million during that time frame.

“The price point was $20,” Garnier said.

He paused.

“Twenty dollars,” he repeated with a tinge of regret in his voice. “And you can eat as much as you want.”

Although the promotion boosted traffic by a few percentage points, Garnier said, the number of people taking advantage of the all-you-can-eat offer far exceeded the company’s projections. In response, they adjusted the price to $22 and then $25.

All-you-can-eat offers can be effective marketing strategies to get people in the door in the competitive world of casual dining — Applebee’s offers $1 margaritas dubbed the Dollarita, buffet chains such as Golden Corral and Sizzler promise abundance at a flat rate, and Olive Garden, one of Red Lobster’s main competitors, has long lured customers with unlimited salad and bread sticks.

But Red Lobster made a few crucial missteps with the shrimp deal, said Eric Chiang, an economics professor at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and a self-proclaimed buffet aficionado.

The company not only started with a low price point, but offered a prized and pricey menu item that can serve as an entire meal — not many customers at Olive Garden, he noted, are going to stock up on bread sticks and salad alone.

“Most people will also order the Taste of Italy,” he said, “or something that gives you meat and pasta.”

Chiang said the most effective loss leaders, a term for products that aren’t profitable but bring in enough new customers or lead to the sale of enough other items to make the offer worthwhile, use cheap ingredients. A good example is 7-Eleven’s Free Slurpee Day, he said, as the company gives away about 15 cents of ice and syrup to customers who then pay to fill up their gas tanks.

Consumers are especially drawn to all-you-can-eat deals and buffets during tighter economic times, Chiang said.

“This is a story of inflation,” he said. “All you can eat for $15? That gives customers a sense of control. Like we’re not being gouged, not being nickel and dimed for every dessert.”

Red Lobster, it turns out, has been in trouble for a while.

In 2003, the chain, which at the time was owned by Darden Restaurants, the company that owns Olive Garden, offered a similarly disastrous all-you-eat crab special for around $23.

So many people came back for seconds, thirds and even fourths, executives said at the time, that it cut into profit margins. Before long, the company’s then-president stepped down.

In 2014, after a period of disappointing sales and less foot traffic, Darden sold Red Lobster to San Francisco private equity firm Golden Gate Capital for more than $2 billion, a stake that was eventually taken over by Thai Union.

Despite the turmoil, the company, which until this week touted about 700 locations, remained a brand so beloved that it earned a reference in Beyonce’s song “Formation,” in which she describes post-coital trips to Red Lobster.

After the song’s release, the company said it saw a 33% jump in sales, but that glow was short lived and had faded long before the ill-fated shrimp deal was brought back last year.

“You have to be pretty close to the edge for one promotion to tip you over the edge,” said Sara Senatore, a senior analyst at Bank of America, who follows the restaurant industry.

In January, Thai Union Group — citing a combination of financial struggles it pinned to the pandemic, high labor and material costs and the oft-cited buzzword of industry “headwinds” — announced plans to dump its stake in the company, which was founded in 1968 in Lakeland, Fla. The closures this week hit at least five California locations — Redding, Rohnert Park, Sacramento, San Diego and Torrance — according to the website of the liquidation company, which posted images of available items, including a lobster tank, seating booths, refrigerators and a coffee maker.

During a presentation to investors in February, Thiraphong Chansiri, the chief executive of Thai Union, expressed frustration with the situation surrounding Red Lobster, saying it had left a “big scar” on him.

“Other people stop eating beef,” he said. “I’m going to stop eating lobster.”

Business

Column: Exxon Mobil is suing its shareholders to silence them about global warming

You wouldn’t think that Exxon Mobil has to worry much about being harried by a couple of shareholder groups owning a few thousand dollars worth of shares between them — not with its $529-billion market value and its stature as the world’s biggest oil company.

But then you might not have factored in the company’s stature as the world’s biggest corporate bully.

In February, Exxon Mobil sued the U.S. investment firm Arjuna Capital and Netherlands-based green shareholder firm Follow This to keep a shareholder resolution they sponsored from appearing on the agenda of its May 29 annual meeting. The resolution urged Exxon Mobil to work harder to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of its products.

Exxon has more resources than just about anybody; ‘overkill’ doesn’t begin to describe the imbalance of power.

— Shareholder advocate Nell Minow

The company’s legal threat worked: Days after the lawsuit was filed, the shareholder groups, weighing their relative strength against an oil behemoth, withdrew the proposal and pledged not to refile it in the future.

Yet even though the proposal no longer exists, the company is still pursuing the lawsuit, running up its own and its adversaries’ legal bills. Its goal isn’t hard to fathom.

“What purpose does this have other than sending a chill down the spines of other investors to keep them from speaking up and filing resolutions?” asks Illinois State Treasurer Michael W. Frerichs, who oversees public investment portfolios, including the state’s retirement and college savings funds, worth more than $35 billion.

In response to the lawsuit, Frerichs has urged Exxon Mobil shareholders to vote against the reelection to the board of Chairman and Chief Executive Darren W. Woods and lead independent director Joseph L. Hooley at the annual meeting.

He’s not alone. The $496-billion California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, the nation’s largest public pension fund, is considering a vote against Woods, according to the fund’s chief operating investment officer, Michael Cohen.

“Exxon has gone well beyond any other company that we’re aware of in terms of suing shareholders for trying to bring forward a proposal,” Cohen told the Financial Times. “There doesn’t seem to be anything other than an agenda of sending a message of shutting down shareholders’ ability to speak their mind.”

California Treasurer Fiona Ma, a CalPERS board member, backs a vote against Woods. “As the largest public pension fund in the country, we have a responsibility to lead on issues that threaten to undermine shareowners,” she says.

The proxy advisory firm Glass Lewis & Co., which helps institutional investors decide how to vote on shareholder proposals and board elections, has counseled a vote against Hooley, citing Exxon Mobil’s “unusual and aggressive tactics” in fighting activist investors.

Exxon Mobil’s action against Arjuna and Follow This opens a new chapter in the long battle between corporate managements and shareholder gadflies.

Fossil fuel companies have been especially touchy about shareholder resolutions calling on them to take firmer action on global warming and to be more transparent about the effects their products have on climate.

In part that may be the result of some significant victories by activist shareholders. In 2021, nearly 61% of Chevron shareholders voted for the company to “substantially” reduce its greenhouse gas emissions — a shockingly large majority for a shareholder vote on any issue. That same year, the activist hedge fund Engine No. 1 led a campaign that unseated three Exxon Mobil board members and replaced them with directors more sensitive to climate risk.

Exxon Mobil also subjected the San Diego County community of Imperial Beach to a campaign of legal harassment over the city’s participation in a lawsuit aimed at forcing the company and others in the oil industry to pay compensation for the cost of global warming, which stems from the burning of the companies’ products.

Even in that context, Exxon Mobil’s campaign against Arjuna and Follow This represents a high-water mark in corporate cynicism.

The lawsuit asserts that the investment funds’ proposed resolution violated standards set forth by the Securities and Exchange Commission governing the propriety of such resolutions — it was related to “the company’s ordinary business operations” and closely resembled resolutions on similar topics that had failed to exceed threshold votes at the company’s 2022 and 2023 annual meetings. Both standards allow a company to block a resolution from the meeting agenda, or proxy.

That may be so, but the conventional practice is for managements to seek approval from the SEC to exclude such resolutions through the issuance of what’s known as an agency “no action” letter.

Exxon Mobil hasn’t taken that step. Instead, it filed its lawsuit in federal court in Forth Worth, where the case was certain to be heard by one of the only two judges in that courthouse, both conservatives appointed by Republican presidents — a crystalline example of partisan “judge shopping.” The case came before Trump appointee Mark T. Pittman, who has allowed it to proceed.

The company hasn’t said why it followed that course. “The U.S. system for shareholder access is the best in the world,” company spokeswoman Elise Otten told me by email. “To make sure it stays that way, the rules must be enforced or the abuse by activists masquerading as shareholders will continue threatening the system.”

In practice, however, the SEC has been quite strict about requiring that shareholder proposals meet its standards. “There can only be one reason” for the lawsuit, says shareholder advocate Nell Minow — “it’s to crush the shareholder. Exxon has more resources than just about anybody; ‘overkill’ doesn’t begin to describe the imbalance of power.”

The company accused Arjuna and Follow This of aiming not “to improve ExxonMobil’s business performance or increase shareholder value,” but of pursuing the goal of “disrupting ExxonMobil’s investments and development of fossil fuel assets and causing ExxonMobil to change its business model, regardless of the benefits, costs, or the world’s needs.”

The company maintained that the shareholder groups aimed to “force ExxonMobil to change the nature of its ordinary business or to go out of business entirely.”

That’s flatly untrue. The resolution observed that the company’s “cost of capital may substantially increase if it fails to control transition risks by significantly reducing absolute emissions.”

That judgment is shared by many institutional investors and government regulators, and points to a path for preserving Exxon Mobil’s business prospects, not destroying them.

In any case, what Exxon Mobil failed to note is that shareholder resolutions are always advisory — they can’t require management to do anything.

In its lawsuit, the company whined about the sheer burden of handling an increase in shareholder resolutions, especially those on fraught topics such as the environment and social issues. Using what it described as an SEC estimate that it costs corporations $150,000 to deal with every submitted resolution, its annual meeting statement calculated that it has spent $21 million to manage 140 submitted resolutions.

A couple of points about that. First, the SEC didn’t estimate that every resolution costs $150,000 to manage. The SEC actually cites a range of $20,000 to $150,000 each.

Second, a quick look at the company’s financial statements gives the lie to its claim that shareholder resolutions are some sort of cataclysmic burden. Its statistics applied to the entire 10-year period from 2014 through 2023, not just a single year.

Over that decade, Exxon Mobil reported total profits of $204.3 billion. In other words, processing those 140 proposals — using the SEC’s highest estimate to arrive at $21 million — cost Exxon Mobil one one-hundredth of a percent of its profits, at most, to deal with shareholder proposals.

And it’s not as if those proposals clog up the annual meeting proxy — for this year’s meeting, only four proposals will be submitted to shareholder votes. Management opposes all four, big surprise.

As for whether companies such as Exxon Mobil have better uses for their money, the proxy statement doesn’t make a great case for every expenditure.

Last year, for instance, the company paid nearly $1.5 million in relocation expenses for its top executives, including about $500,000 for Woods, in connection with the move of its headquarters from the Dallas suburbs to the Houston suburbs, about a three-hour drive away. Over the last three years, Woods collected more than $81 million in compensation, so one can see why moving house would leave him strapped.

“As a shareholder, the one thing you ask for is to look at every expenditure in terms of its return on investment,” Minow told me. “It’s unfathomable that the return on investment of this lawsuit is in any way beneficial to the company.” She’s right: It’s certain that Exxon’s legal fees on this case already exceed the putative $150,000 expense it incurred dealing with the withdrawn proposal.

Exxon Mobil’s punitive lawsuit only hints at the lengths that the fossil fuel industry will go to preserve a business model facing an inexorable decline. The companies haven’t been shy about enlisting politicians to rid them of their turbulent shareholders (to paraphrase the medieval King Henry II).

In February, Sen. Bill Hagerty (R-Tenn.) introduced a measure dubbed the “Rejecting Extremist Shareholder Proposals that Inhibit and Thwart Enterprise for Businesses Act, or “RESPITE.” The act would overturn an SEC rule stating that resolutions dealing with “significant social policy issues” can’t be excluded from the annual proxy under the traditional “ordinary business” limitation.

Don’t expect them to be shy about demanding more latitude from a reelected President Trump. The Washington Post reported last week that Trump pledged to roll back Biden administration environmental policies if the oil executives meeting with him at Mar-a-Lago would raise $1 billion for his campaign. An Exxon Mobil executive was present, the Post reported.

Business

Wonderful Co. sues to halt California card-check law that made it easier to unionize farmworkers

The Wonderful Co. is escalating its battle against unionization of its job sites, looking to halt a new state law intended to streamline the farmworker unionization process. The move comes two months after the United Farm Workers utilized the provision to become the collective bargaining representative for employees of the company’s massive grapevine nursery in Kern County.

Wonderful, the $6 billion agricultural powerhouse owned by Stewart and Lynda Resnick, said Monday it is suing the state Agricultural Labor Relations Board, challenging the constitutionality of the state’s so-called card-check system, which Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law in 2022. Under its provisions, a union can organize farmworkers by inviting them to sign authorization cards at off-site meetings, without notifying an employer, rather than voting by secret ballot at a designated polling place.

The company, whose portfolio includes such well-known brands as FIJI Water, Wonderful Pistachios and POM Wonderful, alleges in its lawsuit that the law deprives employers of due process on multiple fronts. Among them: forcing a company to enter a collective bargaining agreement even if it has formally appealed the ALRB’s certification of a union vote and presented what it believes is evidence that the voting process was fraudulent.

Wonderful said it was compelled to file its lawsuit now because, under the card-check law, the company faces a June 3 deadline to reach a collective bargaining agreement or have one dictated by the ALRB.

“Having been compelled into a constitutionally unlawful procedure that imposes a constitutionally illegitimate certification, Wonderful has no meaningful way to obtain plain, speedy or complete relief other than through an order of this Court declaring that, on its face, [this section of the labor code] is unconstitutional,” the lawsuit said.

The lawsuit, to be heard in Kern County Superior Court, seeks to enjoin the ALRB from enforcing the card-check law’s provisions.

The ALRB did not immediately respond to the The Times’ request for comment.

A spokesperson for Newsom’s office said staff members were still reviewing the complaint, but included in the response Newsom’s comments when he signed the legislation. “California’s farmworkers are the lifeblood of our state, and they have the fundamental right to unionize and advocate for themselves in the workplace,” his statement said in part.

UFW spokesperson Elizabeth Strater said the union was not surprised by Wonderful’s move.

“This is an unfortunate tactic, but it’s not surprising,” Strater said. “They’ll do pretty much anything to prevent workers from being empowered.”

William B. Gould IV, a professor of law emeritus at Stanford Law School, described the card-check system as “an excellent statute to challenge” because of the confusion and ambiguity surrounding some of its provisions and the “potential for contacts between organizers and employees” that could raise questions about whether workers were acting with free choice.

While he predicted Wonderful would have a “difficult time” making its case in California, he said the company could be aiming to take its argument to the conservative-leaning U.S. Supreme Court.

“To paraphrase Frank Sinatra, now we’re in a situation where anything goes,” said Gould, who served as chair of the ALRB from 2014 to 2017.

The lawsuit is the latest salvo in what’s been a tumultuous dispute over the UFW’s unionization campaign at the nation’s largest grapevine nursery.

In late February, the union filed a petition with the labor relations board, asserting that a majority of the 600-plus farmworkers at Wonderful Nurseries in Wasco had signed authorization cards and asking that the UFW be certified as their union representative.

Within days, Wonderful hit back with an explosive allegation: The company accused the UFW of baiting farmworkers into signing the authorization cards while helping them apply for $600 in federal relief for farmworkers who labored during the pandemic. And it submitted nearly 150 signed declarations from nursery workers saying they had not understood that by signing the cards they were voting to unionize.

The ALRB acknowledged receiving the worker declarations; nonetheless, the regional director of the labor board moved forward three days later to certify the union’s petition. She has said in subsequent hearings that she felt she had to move quickly under the timeline laid out in the card-check law, and that at the time she did not think the statute authorized her to investigate allegations of misconduct.

Wonderful appealed the certification, alleging the UFW engaged in fraud to obtain employee signatures on authorization cards. The UFW countered that Wonderful had intimidated workers into making false statements and had brought in a labor consultant with a reputation as a union buster to manipulate their emotions in the weeks that followed.

A hearing on Wonderful’s objections has been playing out before an independent hearing examiner for the past three weeks. The lawsuit seeks to pause the hearing, pending the outcome of the card-check suit.

The UFW, meanwhile, is pursuing its own complaint against Wonderful. The union has filed a formal complaint of unfair labor practices with the ALRB, alleging Wonderful held mandatory meetings where company leaders urged employees to reject the union, circulated an anti-union petition and misrepresented the union’s intentions.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Dems seeking re-election seemingly reverse course, call on Biden to 'bring order to the southern border'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpain and Argentina trade jibes in row before visit by President Milei

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFetterman says anti-Israel campus protests ‘working against peace' in Middle East, not putting hostages first

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoGerman socialist candidate attacked before EU elections

-

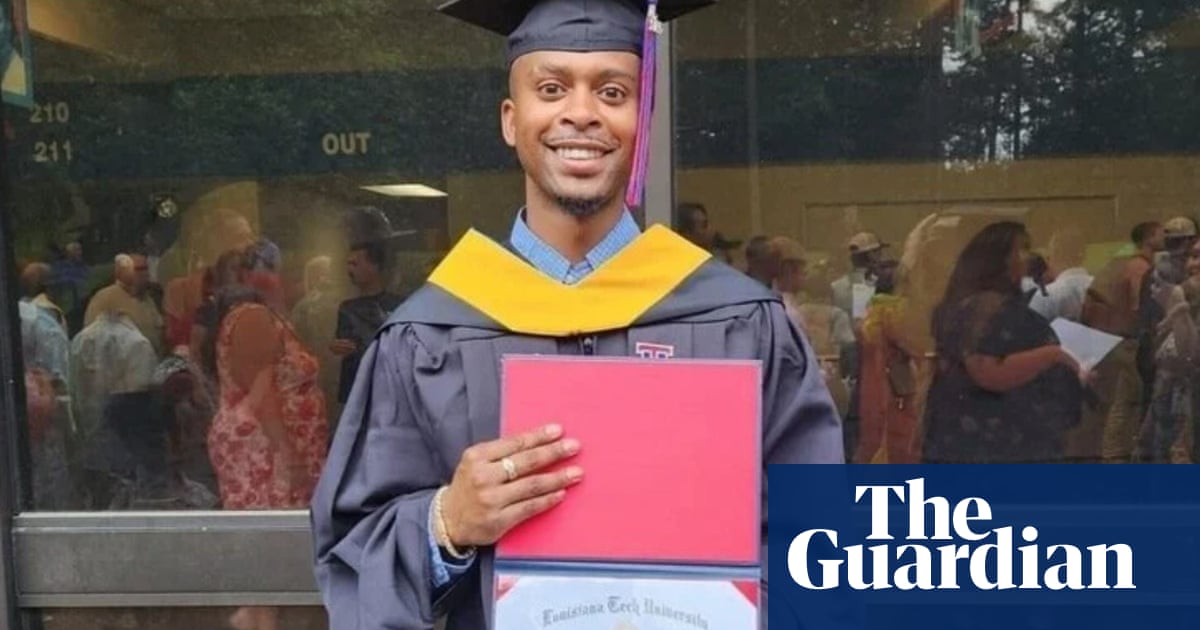

News1 week ago

News1 week agoUS man diagnosed with brain damage after allegedly being pushed into lake

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoGaza ceasefire talks at crucial stage as Hamas delegation leaves Cairo

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRepublicans believe college campus chaos works in their favor

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoConservative beer brand plans 'Frat Boy Summer' event celebrating college students who defended American flag