Business

Charles Munger, who helped build one of the greatest fortunes in U.S. history, has died

Charles Munger helped build one of the greatest fortunes in U.S. history, but he often explained his success in terms that sounded deceptively uncomplicated.

“Take a simple idea and take it seriously.”

“Load up on the very few insights you have instead of pretending to know everything about everything at all times.”

And above all, he stressed the need for patience and a long-term investment view — an approach that has vanished from much of Wall Street in recent decades.

In his trademark curmudgeonly style, Munger advised investors to take stakes in a relative handful of great companies and then “just sit on your ass.”

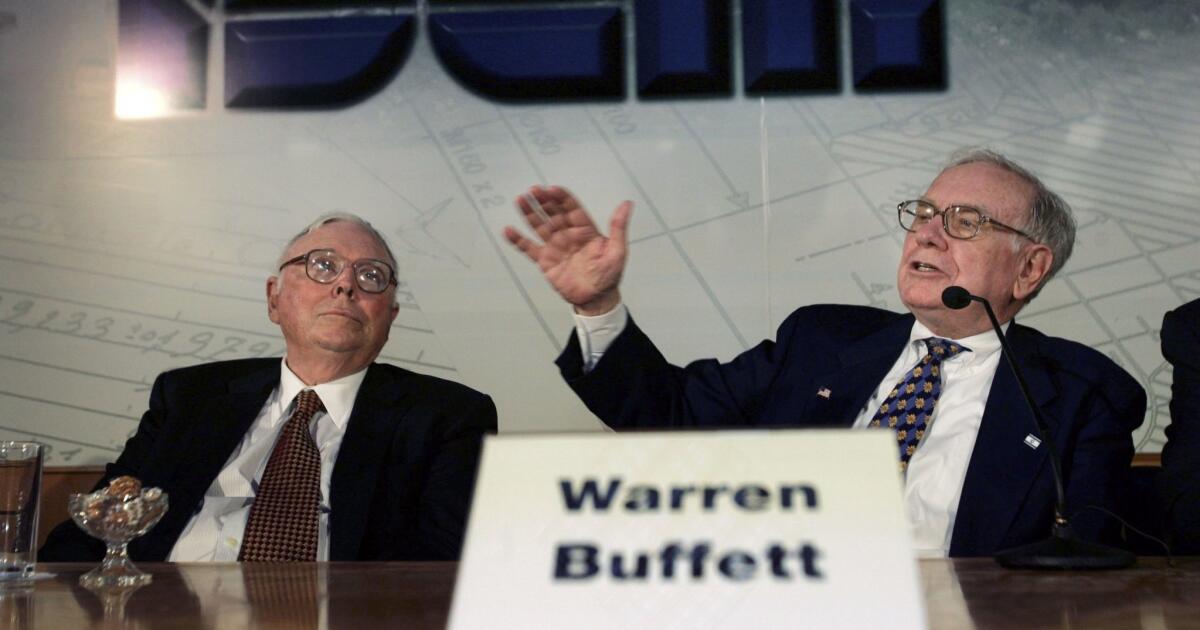

Munger, the longtime investment partner of billionaire Warren E. Buffett, died Tuesday at a California hospital, according to Berkshire Hathaway, where he was vice chairman. He was 99.

“Berkshire Hathaway could not have been built to its present status without Charlie’s inspiration, wisdom and participation,” Buffett said in a news release.

Though born in Omaha, like Buffett, Munger lived in Los Angeles most of his life. And for the most part, he shunned the media spotlight that Buffett often relished.

However, with a net worth that Forbes estimated at $2.6 billion upon his death, he was able to make a big impact with his philanthropy both locally and elsewhere.

He was a longtime benefactor and board chairman of Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles. He also funded a science center at Harvard-Westlake School in L.A. and a research center at the Huntington Library.

In higher education, Munger said he wanted to foster more dialogue and mixing of ideas on campus. In 2013 Munger donated $110 million in stock for a graduate residence at the University of Michigan. He gave $43.5 million in 2004 for a graduate residence adjacent to Stanford Law School.

But it was a 2016 donation that led to perhaps the biggest controversy of his career. He pledged $200 million to build new dorms at UC Santa Barbara, which had a severe shortage of student housing.

He pushed for the construction of an 11-story warehouse-size building that would feature 4,500 beds in small rooms — similar to but larger than the Michigan dorm. Unveiled in 2021, the massive UCSB structure was dubbed “Dormzilla” by its critics, and the university is reportedly considering alternatives.

Munger sometimes was described as Buffett’s “sidekick,” but that grossly understated his influence on Buffett, who is six years his junior.

Berkshire, with more than $1 trillion in assets, owns such well-known brands as insurance company Geico, the BNSF railroad, See’s Candies, Fruit of the Loom and Dairy Queen.

After meeting Munger at a dinner party in Omaha in 1959, Buffett — then an ambitious but novice investor — said he quickly realized that there was “only one partner who fit my bill of particulars in every way: Charlie.”

Buffett’s wife, the late Susie Buffett, once wrote of the two men that “both thought the other was the smartest guy they ever met.”

In the last few decades Munger’s name has become better known, at least among serious investors, as he shared the spotlight with Buffett at Berkshire’s annual shareholder meeting. The two became a nightclub act of sorts, peppering sage investment advice with one-liners that kept the crowd of thousands enraptured.

One of Munger’s most famous zingers encapsulated his frequently acerbic wit: “I’m right, and you’re smart, and sooner or later you’ll see I’m right.”

Charles Thomas Munger was born on Jan. 1, 1924, in Omaha to Al and Florence Munger. His father was a lawyer, and his grandfather had been a federal judge.

As described by Michael Broggie in the 2005 book “Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger,” Munger’s family fared comparatively well during the Great Depression.

Still, young Charlie was expected to work. One of his first jobs was clerking — for $2 per 12-hour shift — at Buffett & Son, an upscale Omaha grocery run by Warren Buffett’s grandfather. But Munger never met the younger Buffett during their youth.

A voracious reader whose hero was Benjamin Franklin, Munger showed an aptitude for business early on when he began to raise hamsters to trade with other kids.

“Even at an early age, Charlie showed sagacious negotiating ability, and usually gained a bigger specimen or one with unusual coloring,” Broggie wrote.

After high school, Munger enrolled at the University of Michigan as a math major, but he left in 1943 to join the war effort. He enlisted in the Army Air Forces and was trained in meteorology at Caltech in Pasadena.

Though he lacked a bachelor’s degree, Munger in 1946 decided to apply to Harvard Law School. He was accepted after a family friend intervened.

Munger excelled at Harvard, graduating magna cum laude. His first law job was at Wright & Garrett in Los Angeles.

But in his personal life, Munger struggled. At age 21 he had married Nancy Huggins, a family friend. They divorced in 1953, when Munger was 29.

Shortly afterward the oldest of their three children, Teddy, was diagnosed with leukemia. He died at age 9.

In 1956 Munger married Nancy Barry Borthwick, a Stanford University economics graduate. They had met through Munger’s friend Roy Tolles. Borthwick had two sons from her first marriage. She and Munger had four more children together.

The size of the family was key to Munger’s fateful decision to shift career tracks from law to investing.

“Nancy and I supported eight children,” Munger said in 1996. “And I didn’t realize that the law was going to get as prosperous as it suddenly got.”

He put it another way to Janet Lowe, who wrote the biography “Damn Right! Behind the Scenes With Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger” in 2000.

“Like Warren, I had a considerable passion to get rich,” Munger told Lowe. “Not because I wanted Ferraris — I wanted the independence. I desperately wanted it.”

In 1962 Munger co-founded the L.A. law firm Munger Tolles & Hills (today known as Munger Tolles & Olson). But by then his investing pursuits were already taking up much of his time.

Though he began trading investment ideas with Buffett in 1959, from 1962 to 1975 Munger was mostly focused on building his own stock investment fund, Wheeler, Munger & Co., according to biographer Broggie.

Munger racked up strong returns in the fund, but, like most investors, he was hit hard in the deep bear market of 1973-74, amid the first Arab oil embargo.

After the market rebounded in 1975, Munger decided to stop directly managing money for others. Instead, he joined with Buffett in investing via the “holding company” concept: The two would buy businesses and make stock investments through a publicly traded company. They would control the firm by virtue of their large stake in it, but other investors could buy the company’s shares if they wanted to join in as essentially silent partners.

Their primary vehicle was Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Munger became vice chairman of the firm in 1978.

Munger also ran a smaller holding company, Pasadena-based Wesco Financial, which was majority-owned by Berkshire. It was merged into Berkshire in 2011. Separately, Munger headed Daily Journal Corp., an L.A.-based publisher of legal newspapers, including the L.A. Daily Journal.

But Berkshire’s success is what made Munger’s name synonymous with brilliant investing.

Buffett credited Munger with refining the former’s basic “value” approach to investing. Buffett was a devotee of Ben Graham, the father of the value school, which preached the discipline of buying shares only in companies that met rigid financial criteria.

Munger, however, convinced Buffett that a long-term investor could prosper by focusing on the very best companies — even if they didn’t meet all of Graham’s value requirements.

Munger’s approach was crystallized in his most famous investing maxim: “A great business at a fair price is superior to a fair business at a great price.”

Munger “expanded my horizons,” Buffett has said.

That, in turn, led to Berkshire’s purchases of huge stakes over the years in such blue-chip companies as Coca-Cola, American Express, IBM and Wells Fargo, in addition to the dozens of companies Berkshire owns outright.

Munger owned only a small fraction of Berkshire stock, but the success of Berkshire Hathaway made him a billionaire anyway.

Later in life, Munger at times became almost apologetic for his financial success. In a 1998 speech he bemoaned the allure of Wall Street for talented young people, “as distinguished from work providing much more value to others.”

“Early Charlie Munger is a horrible career model for the young, because not enough was delivered to civilization for what was wrested from capitalism,” he said.

He was an outspoken critic of excessive executive pay. He and Buffett drew annual salaries of $100,000 at Berkshire, a pittance compared with what most top Fortune 500 executives are paid.

Though a self-described conservative Republican (in contrast to Buffett, a Democrat), on some issues Munger defied the conservative stereotype. He was a longtime supporter of Planned Parenthood, for example, and fought in the 1960s to legalize abortion.

“I’m more conservative, but I’m not a typical Colonel Blimp,” Munger said in 1996, referring to the jingoistic, reactionary British cartoon character.

Munger’s wife, Nancy Barry Munger, died in 2010.

He is survived by eight children and stepchildren, 15 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

Times staff writer Laurence Darmiento contributed to this report. Petruno is a former staff writer.

Business

Sony Pictures CEO Tony Vinciquerra talks 'arms dealer' strategy, defends 'Spider-Man' spinoffs

When Tony Vinciquerra arrived at Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2017, it was far from business as usual.

The Culver City studio was still reeling from a 2014 cyber attack that exposed employees’ personal information and revealed internal communications, damaging its reputation and leading to major financial losses. Its film studio was in such a slump that Tokyo parent company Sony Corp. took a nearly $1 billion write-down just months before Vinciquerra was announced as the new chief executive and chairman.

At the time, he was working at private equity firm TPG after a long career at Fox Networks.

“When people approached me about this job, I really wasn’t looking to go back to work full-time, be in the office every day,” said Vinciquerra, 70. “But what was really attractive was the potential.”

Under his leadership, Sony Pictures mounted a comeback.

The film studio revitalized several franchises, including “Jumanji” and “Bad Boys,” churned out its all-important “Spider-Man” movies and started to capitalize on its sister PlayStation video game division by making film and TV series based on that intellectual property. The studio continued to nurture its key shows “Jeopardy” and “Wheel of Fortune,” weathering host changes for both. And it branched out, making acquisitions in the anime market and in movie theaters.

But the studio also had its share of struggles. Like every studio, Sony’s business was hurt by the pandemic and last year’s dual strikes. The company mounted a failed bid for Paramount Global earlier this year. The film studio’s efforts to expand the “Spider-Man” universe into movies about characters other than the titular superhero have had middling box office results.

On Jan. 2, Vinciquerra will step down from his role and hand control to current Sony Pictures Chief Operating Officer Ravi Ahuja in a planned succession that was signaled for months.

Vinciquerra spoke with The Times ahead of his last day to reflect on his more than seven-year tenure at Sony Pictures and what’s to come for him. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Describe the state of Sony Pictures when you arrived in 2017.

The environment of the studios and the business was still vibrating from the hack. There was so much damage done by that in terms of invasion of privacy and sharing of emails. It was palpable. You could feel it even in June of ’17 when I joined.

The financials showed a lot of room for improvement. The fact that Sony owned pictures, music, PlayStation and technology … there’s no other company in the business that had that combination of assets. I didn’t understand why the company wasn’t trading IP back and forth among its units, and they weren’t really working together. So I saw that as a great opportunity; it’s really why I decided to come here.

What were your main priorities when you started in the job?

All of our competitor companies either had started, or were about to start, general entertainment streaming services, and we were under some pressure to do that as well. But we realized pretty quickly that if everybody else is doing that — all seven or eight of our competitors were doing that — why should we? Knowing that they would be fighting tooth and nail to get subscribers, why wouldn’t we just be the arms dealer to supply the weapons for those streaming services to fight each other and thereby improve our business?

We also, at the time, had 110 cable networks. And it was pretty clear that that business was on the downslope. So we set a strategy to get out of that business for the most part, except in markets where cable networks are still doing really well, which is Latin America, Spain and India.

Looking back at what’s happened with all the streamers, the arms dealer decision looks pretty prescient now.

It was pretty obvious, and also the cable network decision was pretty obvious. And really, what’s going on in the business today, most of the streaming services will become profitable, but the cable networks are going in the wrong direction, and that’s not going to change. That’s really the issue for our colleague companies.

How do you feel about the future for anime?

We haven’t rolled Crunchyroll out in the entire world yet, so we still have quite a ways to go. The audience for anime is violently passionate — violent in a good way, not violent in a bad way. They are the most passionate audience ever. It’s got a great future. And unfortunately, others have noticed now and are starting to get into the business. Netflix and Hulu are starting to get in the business and raise the cost of product for us. But, you know, that comes with success.

Part of your tenure included the strikes, and you’ve commented before on how you feel the contract terms from the unions are increasing costs and forcing productions out of the U.S. Do you think the new California film tax credit proposal will change things?

I don’t think the California change will really impact [the situation] because it still doesn’t cover above-the-line actors, it doesn’t cover casting, and it’s still a very difficult process to get done in California.

Not only did the union deals raise costs, but California raises costs as well, just the regulations and the hoops that you have to jump through to get production done here. My suggestion would be, as I’m leaving this job, is that they take a real hard look at the program and the restrictions on the business and and try to figure that out.

How do you feel about the performance of the film studio during your tenure?

We’ve had mostly very, very good results. Unfortunately, [“Kraven the Hunter”] that we launched last weekend, and my last film launch, is probably the worst launch we had in the 7 1/2 years so that didn’t work out very well, which I still don’t understand, because the film is not a bad film.

But we’ve been very successful. We’ve beat our budgets every year I’ve been here, even through strikes and COVID, and max bonuses several of the years for all the employees. It was a good run, and the film studio was a big part of it.

Going back to “Kraven the Hunter,” and Sony had “Madame Web” earlier this year, which also underperformed …

Let’s just touch on “Madame Web” for a moment. “Madame Web” underperformed in the theaters because the press just crucified it. It was not a bad film, and it did great on Netflix. For some reason, the press decided that they didn’t want us making these films out of “Kraven” and “Madame Web,” and the critics just destroyed them. They also did it with “Venom,” but the audience loved “Venom” and made “Venom” a massive hit. These are not terrible films. They were just destroyed by the critics in the press, for some reason.

Do you think that the “Spider-Man” universe strategy needs to be rethought?

I do think we need to rethink it, just because it’s snake-bitten. If we put another one out, it’s going to get destroyed, no matter how good or bad it is.

How do you feel about the state of the industry going into 2025?

There’s a period of asset readjustment coming. It’s going to be for the next year and a half to two. I think it’s going to be a little bit chaotic. The one thing we do know for sure is that the demand for entertainment is not going down. It’s becoming slightly different. But once all of these companies get to the point where they’re stable, they’ll have a great run ahead of them.

2026 is going to be a great year in the film business. And the television business is still perking along, and our market share keeps going up, so we’re very content there. And then we’re looking at other businesses. The film and TV business are probably not going to be great growth businesses, but we’re looking at other things. We have Crunchyroll, we have Alamo Drafthouse and we’re looking at location-based entertainment projects. I’m pretty comfortable with where the company is right now. It’s very stable, relative to the rest of the business.

What made Sony interested in the Alamo Drafthouse deal?

It’s a very different, very unique concept for viewing a film. It’s a very small business. So we have to grow into the markets that are important to domestic box office.

Alamo, even though it only has 41 locations, has 4.5 million loyalty program members, so we have a built-in way to talk to their customers. That’s going to be a very, very big advantage of it for us in the future. And secondly, the customer profile of Alamo Drafthouse is not terribly dissimilar to Crunchyroll. So we’ll use it to promote Crunchyroll, and we’ll also use it in a lot of other ways. It was not a big cash outlay, but the results of what we’re going to gain from this by having a view of our customers’ likes and dislikes will benefit us greatly in the long run.

After you step down, you’ll be moving into an advisor role for 2025. What does that role look like?

I’m here to answer questions, and I’ll be doing some work with Sony Tokyo, but I’ll be in a different office, hidden away so nobody can find me. I don’t know. We’ll see how it works out.

What are your plans for the future?

I don’t know yet. I’ve had a lot of outreach from private equity firms and and other investment-oriented companies. I’m not going to think about it until after the holidays. But most likely will involve some return to private equity or investment companies, but not for sure.

How would you describe your legacy at Sony Pictures?

Where I get my psychic reward is helping people to do their jobs better and get better in their careers, and that’s really how I judge how well I do. The second part of that corollary is to leave a place better than I found it. And I think I’ve done that most every place I’ve been at. I like to fix things and that’s really how it all comes together.

I think I’m leaving the place in a better place, but time will tell. It feels like it’s a very stable business, and I think that’s the legacy.

Business

After court loss, Albertsons and Kroger trade accusations over demise of mega-grocery-chain deal

When Kroger and Albertsons announced plans in 2022 to team up on what would be the largest supermarket merger in U.S. history, the two grocery store chains highlighted their shared values.

Now their relationship has turned sour, with each side blaming the other for the demise of what would have been a landmark deal.

A day after a federal judge temporarily halted the merger, Albertsons said Wednesday that it’s scrapping the controversial pairing and suing Kroger, alleging that the chain failed to do enough to win over regulators.

Once partners, the grocery chains are now accusing each other of breaching the merger agreement and acting in their own interests.

The fallout between Kroger and Albertsons and the failed merger raise fresh questions about the future of their businesses and the effect on people who shop at their stores. The companies, which have a big presence in California and nationwide, banked heavily on the benefits of joining forces to better compete with the likes of Walmart, Costco and Amazon.

“Anytime you get these two companies fighting with each other, that’s money that could be used for innovation and to better position themselves in the market,” said Christine Bartholomew, a law professor at the University at Buffalo.

The legal battle between the major grocery chains is the latest development in what has been a tumultuous two years for Albertsons and Kroger as they tried to win government approval for their megamerger. In February, the Federal Trade Commission sued to block Kroger’s proposed $24.6-billion acquisition of Albertsons because of concerns that it would eliminate competition, drive up food prices and harm workers.

If the merger had been approved, the two supermarket chains would have run more than 5,000 stores in 48 states, according to the FTC’s lawsuit. Albertsons owns the well-known brands Pavilions, Safeway and Vons. Ohio-based Kroger operates Ralphs, Food4Less, Fred Meyer, Fry’s, Quality Food Centers and other popular grocery stores.

The FTC’s lawsuit set the stage for a three-week trial that kicked off in a federal courtroom in Oregon over the summer. The trial featured testimony from the grocery store chains’ executives, FTC lawyers, union leaders and antitrust experts.

To address concerns about reducing competition, Kroger and Albertsons said they would sell more than 570 stores to C&S Wholesale Grocers. That plan included offloading 63 California stores, including some in Los Angeles and Huntington Beach.

The fate of those stores is unclear. Albertsons didn’t respond to questions about whether they planned to keep or close the California stores. During the trial, Albertsons said it might have to lay off workers and shutter stores if the merger didn’t go through.

The grocery chains, though, failed to convince U.S. District Court Judge Adrienne Nelson, who on Tuesday issued a preliminary injunction blocking the merger, finding that it would quash competition and leave consumers in many parts of the country without meaningful choices when shopping for food. Kroger and Albertsons also faced legal battles in other states, including in Washington, where a judge also blocked the deal Tuesday because of competition concerns.

Noting that Kroger and Albertsons are rivals, the federal government contended that reducing competition between the two would drive up grocery prices.

Kroger and Albertsons vowed to invest in lowering grocery prices if the merger went through, but the judge said in her ruling that courts should be skeptical of promises that can’t be enforced and “business realities” might force the grocery chains to alter these plans.

She also said in her ruling that the grocery chains might end up abandoning the merger because of the court order but it doesn’t force them to do so. “Any harms defendants experience as a result of the injunction do not overcome the strong public interest in the enforcement of antitrust law,” she said.

The judge’s decision to block the merger garnered praise from the FTC, the White House and United Food and Commercial Workers locals, which noted that Kroger and Albertsons have “wasted” billions of dollars on what is now a failed merger.

“Now is the time for Kroger and Albertsons executives to honor their promises to consumers and workers under oath during the trials by investing in lower prices, higher wages, and other investments to improve competitiveness,” UFCW local unions, which represent more than 100,000 workers at Albertsons- and Kroger-owned stores, said in a statement.

A variety of factors including competition and worker wages can affect food prices. Tuesday’s ruling, though, suggested that the judge, who cited economic analysis from the federal government’s expert in her 71-page decision, “didn’t really buy the arguments that Kroger and Albertsons were making, that this would be good for consumers,” Bartholomew said.

The legal blows made it more risky for Kroger and Albertsons to continue the merger plan.

Shortly after the ruling, the grocery chains turned on each other.

“Kroger’s self-serving conduct, taken at the expense of Albertsons and the agreed transaction, has harmed Albertsons’ shareholders, associates and consumers,” Tom Moriarty, Albertsons’ general counsel and chief policy officer, said in a statement.

Erin Rolfes, a spokeswoman for Kroger, disputed Albertsons’ claims, calling them “baseless and without merit.”

“This is clearly an attempt to deflect responsibility following Kroger’s written notification of Albertsons’ multiple breaches of the agreement, and to seek payment of the merger’s break fee, to which they are not entitled,” she said in a statement.

Albertsons’ lawsuit filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery is temporarily under seal, according to a statement.

The Boise, Idaho-based company is seeking a $600-million termination fee and billions of dollars in damages from Kroger as part of the lawsuit.

On Wednesday, Kroger’s stock closed up nearly 1% at $61.33, while Albertsons’ stock fell more than 1% to $18.23. Albertsons’ shares have dropped about 20% this year.

Business

On a quest for global domination, Chinese EV makers are upending Thailand's auto industry

BANGKOK — Japanese car factories in Thailand — which for decades has been the premiere hub of auto manufacturing in Southeast Asia — are shutting down or scaling back.

Subaru said it will stop producing cars at its plant this month. Suzuki plans to cease operations by the end of 2025. And Honda and Nissan say they are reducing production.

The primary culprit: Chinese electric vehicles.

As the world embraces zero-emission vehicles, Thailand has been courting Chinese automakers, which in their quest for global dominance have spent more than $1.4 billion here as of last year to build EV factories.

“Japanese automakers are under significant pressure to cut costs to compete with Chinese brands,” said Larey Yoopensuk, chairman of the Federation of Thailand Automobile Workers. “They are now questioning whether staying in Thailand is still worthwhile.”

Thailand’s government — which wants 30% of the cars it produces to be electric by 2030 — sees Chinese investment as a crucial piece of the future of its auto industry, which now accounts for 800,000 jobs and 10% of the country’s GDP.

The paradigm shift has become a source of anxiety for Thai auto workers, who have long helped produce Japanese cars and the parts that go into them, including exhaust pipes, brakes and doors. Even if Chinese factories replace Japanese ones, Yoopensuk worried that there may not be a place for him or his colleagues in the new order.

One reason is that Chinese companies in Thailand have historically been intolerant of labor unions.

“Over the past decade, this industry has been booming, with unionized workers achieving better living conditions and high incomes,” said Yoopensuk, who has worked in auto manufacturing for 35 years. “If forced out, many workers — particularly older ones — may struggle to find jobs elsewhere.”

He was also concerned that Chinese EV manufacturers would use more automation and favor immigrants from China and Vietnam over Thai workers when hiring.

“This is an issue we’re pushing back against, encouraging these companies to also create employment opportunities here,” he said.

China’s foray into Thailand’s auto industry could herald what’s to come in other parts of the world, as EV adoption grows and Chinese brands go global. Last year, the Chinese behemoth BYD, which opened a factory in Thailand this summer, briefly surpassed Tesla in global sales.

“I don’t think there is any real precedent where those Chinese EV manufacturers are reshaping the industrial landscape in another country,” said David Williams, an expert on labor standards and supply chains in Asia for the International Labor Organization.

Thailand exports just over two-thirds of the cars it makes, with the biggest share going to Australia followed by Saudi Arabia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Its most important market is domestic, and the news has been dismal. Total passenger car sales in Thailand fell 23% through September compared to the same period last year. Experts blamed rising household debt and increasingly stringent rules for securing auto loans.

Electric cars — nearly all of them Chinese — were the one bright spot, with sales up 11%.

Gasoline-powered cars still make up more than 90% of all sales in Thailand, but that is expected to fall as the government continues its push for EVs with subsidies for buyers and manufacturers.

BYD said its new plant would eventually generate about 10,000 jobs and produce 150,000 vehicles a year. When the company launched in Thailand, its distributor offered steep discounts on several models, bringing the cheapest models below $25,000.

That has intensified a price war that further threatens Japanese brands, which are fighting to keep up with cleaner cars of their own.

According to the Thai government, they have committed to investing more in local production of hybrids — which run on both battery motors and internal combustion engines — and electric pickup trucks. Honda started producing EVs in Thailand last December.

As gas-powered cars fall out of favor, some auto parts will be rendered obsolete, such as hydraulic-based steering systems and alternators.

The Thai Auto Parts Manufacturers Assn. has reportedly estimated that only about a dozen of the more than 600 auto parts makers in Thailand will be able to supply Chinese EVs.

Those that can transition to making parts for electric cars may still struggle to compete with Chinese rivals. Some auto parts suppliers have already shuttered as business has contracted.

Supat Ratanasirivilai, managing director of Thai Metal Aluminum, which produces aluminum-made parts for Japanese and American cars, said he has been negotiating with Chinese automakers since the start of the year.

But those talks have stalled since Chinese companies told him that his prices are 30-40% too high.

“We were hoping that when the Japanese carmakers’ production dropped, we may get some benefit from the Chinese carmakers,” he said. “But obviously they are not buying from the Thai suppliers.”

His company is pushing the Thai government to implement more protective measures for local workers, such as requiring EVs to be built with more locally sourced parts.

“The Thai government is really opening up everything for the Chinese carmakers. It has been very difficult for us,” he said. “I don’t know what’s to come next.”

Special correspondent Poypiti Amatatham in Bangkok contributed to this report.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png) Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoGoogle’s counteroffer to the government trying to break it up is unbundling Android apps

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoNovo Nordisk shares tumble as weight-loss drug trial data disappoints

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoIllegal immigrant sexually abused child in the U.S. after being removed from the country five times

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days ago'It's a little holiday gift': Inside the Weeknd's free Santa Monica show for his biggest fans

-

Lifestyle6 days ago

Lifestyle6 days agoThink you can't dance? Get up and try these tips in our comic. We dare you!

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoFox News AI Newsletter: OpenAI responds to Elon Musk's lawsuit

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png) Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoThere’s a reason Metaphor: ReFantanzio’s battle music sounds as cool as it does

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoFrance’s new premier selects Eric Lombard as finance minister