Business

Cameras, cops and paranoia: How Amazon’s surveillance network alters L.A. neighborhoods

Ed Dorini’s house sits at the end of a cul-de-sac that snakes its way up a hill in the Sun Valley area, one of Los Angeles’ northernmost corners. It’s a small enclave whose residents are a little whiter and a little wealthier than the rest of Los Angeles. In this neighborhood, “people take care of their properties,” Dorini said in an interview in his home in late May.

Dorini, 64, came to L.A. as an immigrant from Canada in the early 1980s when he “literally had nothing” and built a business in real estate. The home he owns is one he earned with hard work, which includes remodeling parts of the house himself. He’s proud of it, and he’s intent on keeping it safe: Three years ago, he installed 10 Ring cameras to monitor his property and its various entrances.

“Everybody here has guns and dogs. People aren’t afraid to use them, and I think that’s probably a deterrent,” he told the Markup. “And cameras are, too.”

At times, he’s also found Ring’s companion app, Neighbors, useful. Both Neighbors and Ring are owned by Amazon, and the former is a social platform where Ring doorbell users — and people who join the app independently — can publish posts and footage about things happening in their neighborhood, such as theft or missing pets.

In February 2022, Dorini wrote two posts with accompanying videos about what he considered a safety issue: “Illegal dumping onto [name of street redacted] drive. Anyone recognize this truck.” Ten minutes later, he wrote: “Anyone recently have a bathroom demoed by someone with this big dump truck. Call me.”

This article was co-published with The Markup, a nonprofit, investigative newsroom that challenges technology to serve the public good. Sign up for its newsletters here.

Both of these posts landed in the inbox of 15 officers with the Los Angeles Police Department who had opted in to receive crime alerts posted on Neighbors. Dorini’s post was one of more than 13,000 Neighbors posts published by Angelenos that were automatically forwarded to LAPD officers, detectives and sergeants in just over two years, according to email correspondences that the Markup received via public records requests.

Neighbors has built a forum in which private citizens can monitor one another in service of keeping neighborhoods “safe,” as the company puts it.

That raises important questions: Safe for whom, and from what? While homeowners may believe their cameras and posts are preventing break-ins and theft, some research has shown that surveillance is a poor deterrent of such property crimes. And by trusting their cameras to keep watch for them, users render themselves blind to the ways in which community surveillance breeds paranoia, perpetuates prejudice and puts people at heightened risk of police or vigilante violence.

In the United States, where police disproportionately kill, harm and jail Black, Latino and Indigenous people at a higher rate than white people, this translates into an additional risk to people of color. That is particularly true when, as the Markup’s analysis of Neighbors posts in L.A. and research from other academics has found, its most active users live in whiter, more affluent areas.

Neighbors is “a continuation of a long history of communities coming together and creating their own surveillance systems that shape who they believe belongs somewhere and who doesn’t belong somewhere,” said Ángel Díaz, visiting assistant professor at USC Gould Law School. “And that is something that we have enshrined not only through law enforcement, but through laws around disorderly conduct and things like that.”

The Markup worked with students from the NYCity News Service at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at City University of New York to perform the public records requests (full disclosure: Craig Newmark is also a funder of the Markup).

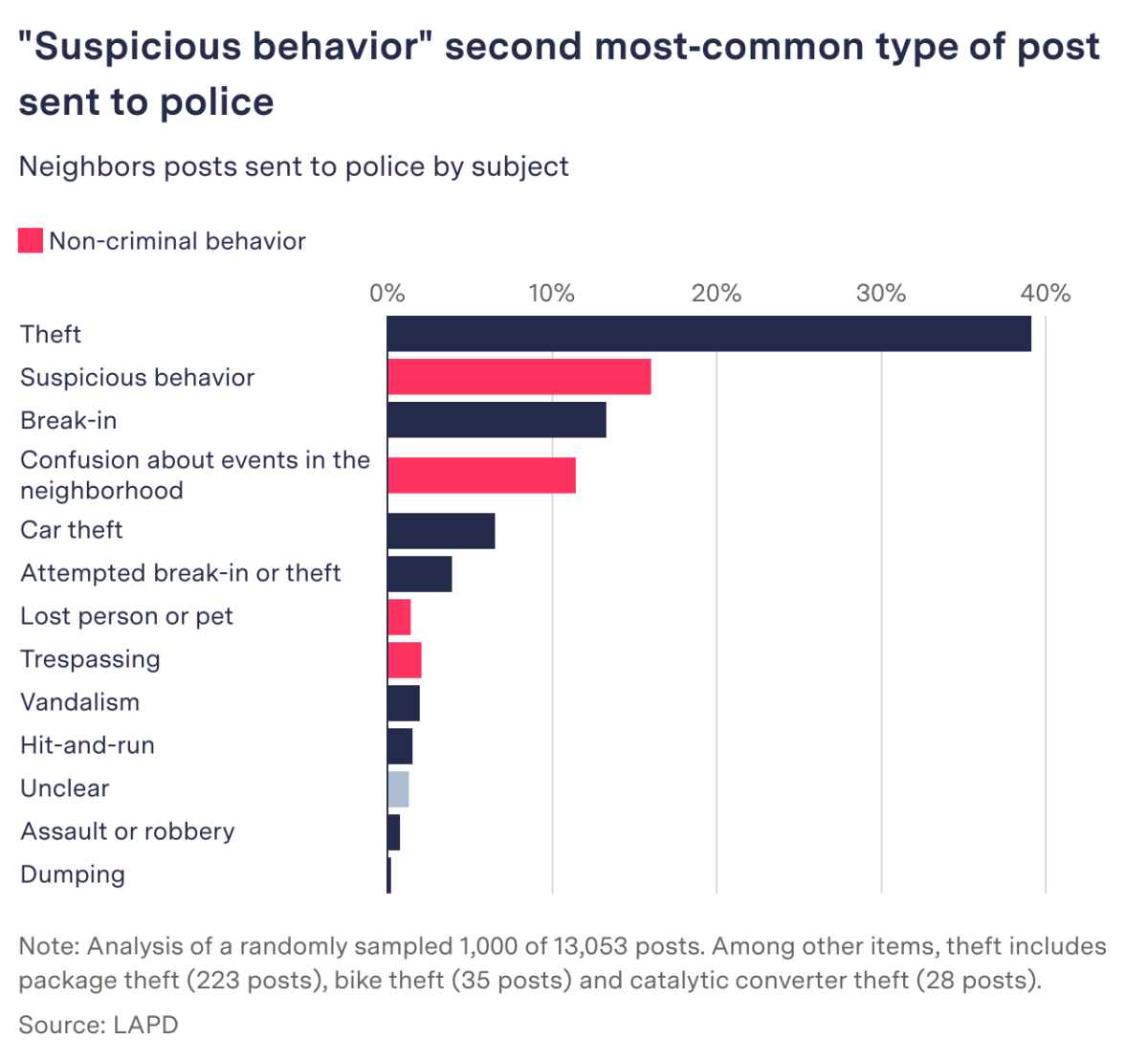

Our analysis of a random sample of Neighbors posts found that more than 30% of the posts the LAPD received did not describe criminal activity, even if users classified them as “crime.” The content of these posts often included behavior residents deemed suspicious, such as someone “checking cars.” According to emails between Neighbors employees and the LAPD, only posts classified as “crime” were supposed to be forwarded to officers — but this did not always happen. Dorini, for example, classified his posts that landed in officers’ inboxes under “safety.”

“Reports of suspicious behavior are coded ways of saying someone does not belong, which in many affluent areas correlates with targeting people of a different race,” Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a professor of law at American University and author of “The Rise of Big Data Policing: Surveillance, Race, and the Future of Law Enforcement,” said in an email.

“In affluent communities that rely on police to keep out ‘the other,’ they will feel more comfortable reporting the suspicion,” Ferguson said. “In less affluent communities that have more complex relationship[s] with the police, the decision to report suspicion will be more circumspect.”

As of September, 2,604 police departments across the United States have forged partnerships similar to LAPD’s with Amazon’s Ring network. In addition to that, 589 fire departments and 66 local government agencies have also signed on. It’s part of a marketing strategy at Ring that targets not just retail customers but also law enforcement agencies, without always making the relationship between police and Ring fully clear to its consumers.

The Markup reached out to 24 consumers whose posts were forwarded to LAPD officers, and three people responded. None were aware that their information had been subject to police monitoring, though they had differing perspectives on the role of law enforcement.

One person, Lenin, who did not want to give his last name, was surprised and said it was “not cool” that LAPD was receiving these alerts.

The majority of people interviewed, however, were unfazed.

“Honestly, I don’t really care either way, you know,” said Dorini’s neighbor, Juan Longfellow. “Everyone has cameras. So, I mean, it’s kind of everywhere. … I’m not one of those people who’s afraid for my privacy or whatever.”

When the Markup told Dorini about Neighbors sending posts to police, he was delighted.

“I like it,” he said. “If [police] got thousands of other ears and eyes out there, [helping] them get involved with, you know, dealing with issues — well, for me, that’s a good thing.”

Ring‘s policy is not to hand over footage from consumer doorbell cameras to authorities unless they have a warrant or there’s a life-threatening situation. Ring spokesperson Mai Nguyen said that posts on Neighbors do not reveal the addresses of users or the Ring device’s owner. Footage and information posted on Neighbors, however, are allowed to be shared, according to the terms of service.

Moreover, although Ring refers to its programs with police departments as “partnerships,” the LAPD’s spokesperson doesn’t see it as one.

“We do not work specifically with RING. We work with citizens, or whoever has a RING system, as part of a crime investigation,” wrote Officer Drake Madison in an email response to a query from the Markup. “Video surveillance is a great tool. Unfortunately, we will not be speaking on the RING system at this time,” he added in a final email.

‘A neighborhood thing’

In its ethnic and economic makeup, Dorini’s neighborhood is typical of those where Ring camera users tend to be concentrated. Walking in the neighborhood, security systems are prevalent — half of the two dozen homes on Dorini’s block have visible cameras.

Even though crime rates ticked up between 2018 and 2022 in Los Angeles, they were still well below levels in the 1990s, and the crime rates in Dorini’s area and adjacent neighborhoods remained the same or decreased between 2018 and 2022, according to a USA Today analysis of data collected by the nonprofit Crosstown.

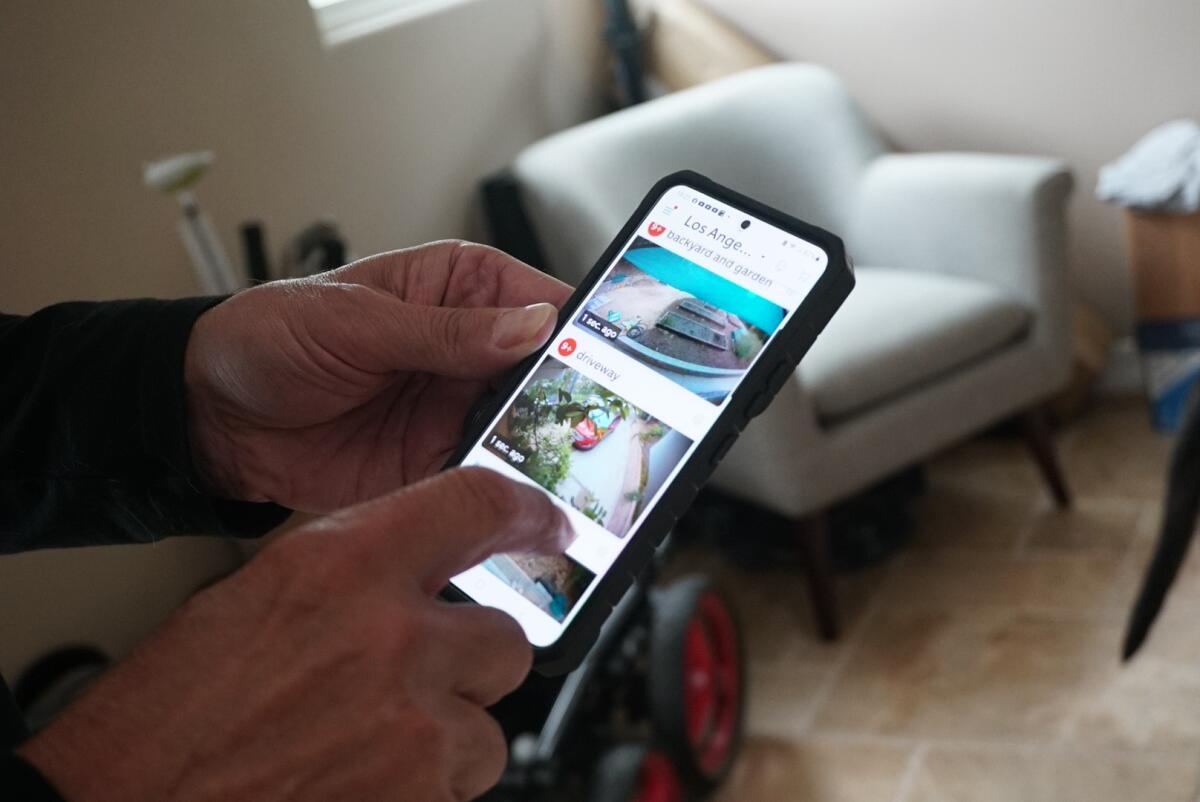

Ed Dorini checks his cameras using the Ring app on his phone.

(Lam Thuy Vo)

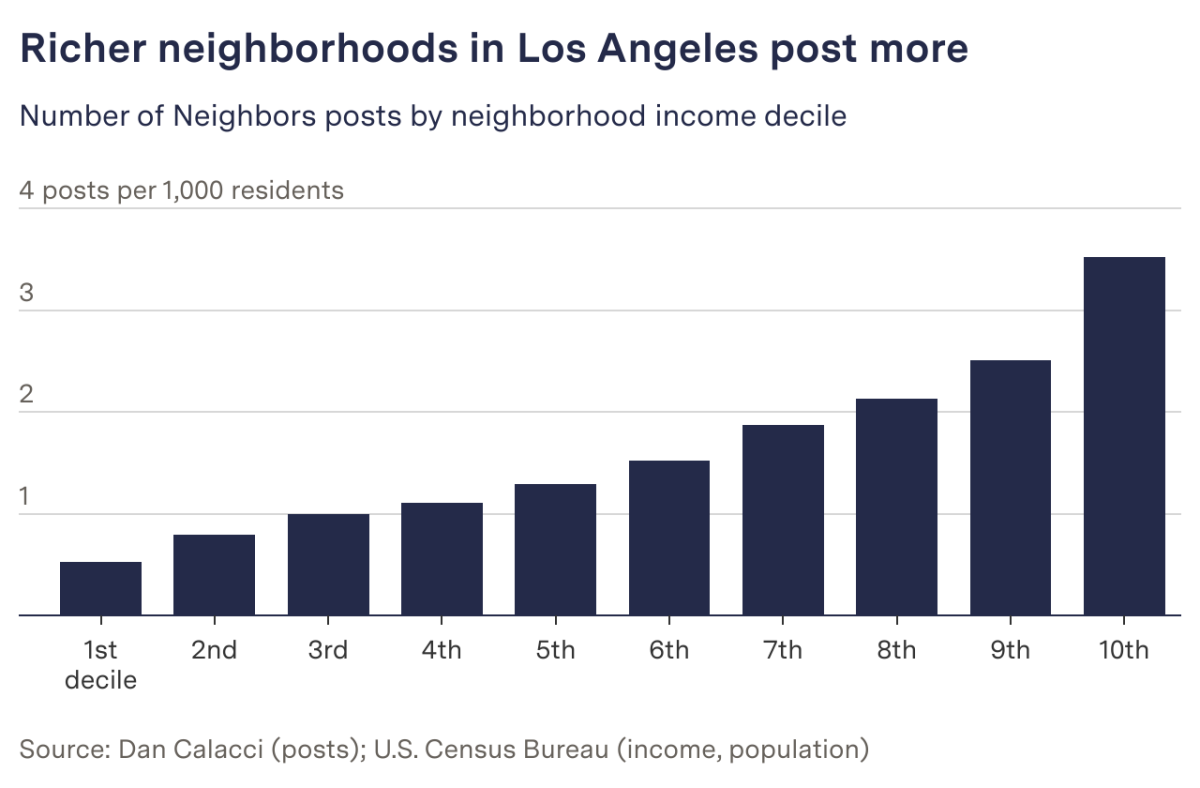

The Markup analyzed the connection between income and Ring camera usage using a database of Neighbors posts from 2018 to 2020 that Princeton researcher Dan Calacci shared with the Markup. The Markup narrowed down the database, which consists of nearly 875,000 posts, to only Neighbors posts located in 25 of the biggest cities in the U.S. where Ring partnered with the police, and found that Los Angeles was among four cities where users in neighborhoods with higher income levels tended to post more often.

When the Markup further analyzed Neighbors posts published in 2019 in Los Angeles, an even clearer trend emerged: Richer areas of the city posted roughly six times more on Neighbors than poorer areas.

Much of what Dorini and his wife would see on their Ring footage was wildlife — cheeky coyotes crawling through backyards or deer trotting along — but it was also a way to keep an eye on the property and keep people from “monkeying around our house.” As he scrolled through the Ring app, it displayed live feed after live feed of the spaces around him.

Being a Ring owner gave him a different benefit, too, he said. “We didn’t really realize that it was going to have a network situation. […] We noticed that it started to become like a neighborhood thing.”

The neighbors on this block all know one another, and they will often work together to ensure their homes are safe, Dorini said. Once, he said, he and his neighbors used their security camera footage to help police track down an alleged burglar who had walked through their backyards. Dorini said he was unaware of whether the person was accused of stealing in their neighborhood.

Elsewhere in the Sun Valley area, one person wrote a post in 2018 — which was categorized as “suspicious” — about a “Hispanic man with sleeping bag.” “Male Hispanic in his 20’s with a sleeping bag was hanging out by our driveway,” the post read. “Asked him to leave twice and he said he had been hiking and said he used sleeping bag to sit on his hike. We told him to leave as he doesn’t belong here and he got very annoyed, and a neighbor followed him down the street. Please be careful!”

In response to questions from the Markup, Ring spokesperson Nguyen offered a statement providing an overview of Ring’s work with police and its content moderation policies.

“Ring does not tolerate racial profiling and hateful content when it comes to content on Neighbors,” Nguyen said. “We’ve invested many resources to help us deliver on this commitment — Neighbors has strict community guidelines, trained moderators, user flagging capabilities, and other tools in place to help create a safe place for all members of the community. We prompt users to review their posts for potential bias before submitting to Neighbors, and all content submitted to our app is reviewed before it’s published to help ensure it adheres to our community guidelines.”

Ring updated its guidelines in 2021 to require community members to publish posts based on actions they’ve observed or recorded, rather than on suspicions. On the website it said that “Neighbors acknowledges that posts reporting concerns about an individual can be influenced by implicit bias and profiling — even if unintentional.” It is unclear how much of an effort Ring has made to ensure that people follow these guidelines.

“The paranoia of somebody’s imagination is making its way into that of other people,” said Díaz, the visiting law professor at USC, about neighborhood platforms like Neighbors. “And so, if you’re just passively keeping up with alerts and read them and move on with your day, you get inundated with this fear that your neighborhood is very unsafe, based on unsubstantiated accusations that are oftentimes more reflective of people’s own prejudices than anything else.”

Calacci’s analysis of his own database of Neighbors posts found that people who are homeowners and live in white “enclaves” (white neighborhoods surrounded by other white neighborhoods) are more likely to post on the platform. His analysis also showed that majority-white neighborhoods that tend to call 311 to sweep homeless encampments also post more on the Neighbors platform.

“Such calls bear the closest resemblance to the notion of neighborhood gatekeeping — they literally entail policing presence and belonging in a neighborhood,” Calacci wrote in his paper, which was published last year.

In 2021, the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition audited the Police Department’s Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR) program, in which community members were encouraged to report suspicious activities to help officers prevent terrorism attacks. The coalition’s analysis showed that close to 60% of reports were filed in communities that were predominantly white, and that roughly half of them were deemed unfounded.

Hamid Khan, the coalition’s founder, said programs like SAR show that police will often hear from anonymous voices from largely white neighborhoods. Technology like Neighbors’ email alerts to LAPD just streamlines this process, “so that’s where the license for racial profiling comes in,” he said.

No choice but to move

Drive south from Dorini’s home for about an hour — down to near Broadway and 92nd Street — and you’ll find yourself where Ernie Arzu lived when a Neighbors post he wrote about a friend’s missing dog got forwarded to the LAPD.

His post about a Yorkshire Terrier named Bella Dior was like many others in his neighborhood: Missing animals posts made up about half of the 12 Neighbors posts the Markup was able to identify in Calacci’s database to be from his area. The neighborhood is 77% Latino and 19% Black; by comparison, Dorini’s is 64% white, 20% Latino, 12% Asian and 2% Black.

Only one post from Arzu’s area of South Los Angeles was categorized as suspicious behavior.

Arzu had bought a Ring camera, largely to keep an eye on his 15-year-old daughter who he said “sometimes likes to sneak out,” but doesn’t check in on the footage all that much.

Arzu is a Black personal trainer and caretaker, whose family is originally from Belize. He’s lived in the city since 1986, when he moved there as a 10-year-old.

“I’ve been in L.A. for as long as I can remember,” he said.

The crime rate in his neighborhood is 93 crimes per 1,000 residents, compared with the citywide average of 60 per 1,000 residents. But despite people who live in the area experiencing more crime than the average Angeleno, Arzu said that LAPD would rarely help.

The only time Arzu called the police when he was living there was when he saw “young kids” vandalize a neighbor’s home. The police did not arrive at the scene until five hours after the call, he said. Arzu was doing yard work in his front yard when the officers arrived. Instead of looking for the teens who had destroyed his neighbor’s property, Arzu said, they asked him for his ID, assuming he did not live at his residence.

“[The LAPD] don’t really mess with us. There’s nothing positive. And it’s nothing negative,” he said.

Past research has shown that Black people experience more violence and harassment from police, as well as harsher policing strategies, than their white counterparts. Tufts University Assistant Sociology Professor Daanika Gordon describes how in more affluent, white neighborhoods, police act as “responsive service providers” while Black populations are simultaneously oversurveilled and socially controlled — not to mention neglected and underpoliced when it comes to emergency services.

But the lack of help also had a different effect: Arzu’s wife would obsess over crime on Neighbors. She felt unsafe in the neighborhood, so Arzu and his family recently decided there was no other recourse than to move away.

“My wife wants to move. She [doesn’t] like the neighborhood. There’s crime,” he said. “I don’t see no crime, but apparently there is. Then you know, it’s just a little quiet neighborhood to me.”

NYCity News Service writers Randi Love, James O’Donnell, Ariana Perez-Castells, Natalia Sánchez Loayza and Paisley Trent contributed to this report.

This series was made possible through support from the Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network.

Business

How Poshmark Is Trying to Make Resale Work Again

Lauren Eager got into thrifting in high school. It was a way to find cheap, interesting clothes while not contributing to the wastefulness of fast fashion.

In 2015, in her first year of college, she downloaded the app for Poshmark, a kind of Instagram-meets-eBay resale platform. Soon, she was selling as well as buying clothes.

This was the golden age of online reselling. In addition to Poshmark, companies like ThredUp and Depop had sprung up, giving a second life to old clothes. In 2016, Facebook debuted Marketplace. Even Goodwill got into the action, starting a snazzy website.

The platforms tapped into two consumer trends: buying stuff online and the never-gets-old delight of snagging a gently used item for a fraction of the original cost. During the Covid-19 pandemic, as people cleaned out their closets, enthusiasm for reselling intensified. It was so strong that Poshmark decided to go public. On the day of its initial public offering in January 2021, the company’s market value peaked at $7.4 billion, roughly the same as PVH’s, the company that owns Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, at the time.

Then, the business of old clothes started to fray.

Using the Poshmark app, Ms. Eager and others said, started to feel like trying to find something in a messy closet. The app was cluttered with features that did not work or that she did not use, and it felt “spammy,” she said, sending too many push notifications.

Many platforms found selling used items hard to scale. Now, online resellers are trying to recalibrate. Last year, ThredUp decided to exit Europe and focus on selling in the United States. Trove, a company that helps brands like Canada Goose and Steve Madden resell their goods, purchased a competitor, Recurate. The RealReal, a luxury consignor, appointed a new chief executive as the company tried to improve profitability.

Poshmark is undergoing perhaps the biggest reinvention. In 2023, Naver, South Korea’s biggest search engine as well as an online marketplace, bought the company in a deal valued at $1.6 billion, less than half its IPO price.

Something of a mash-up of Google and Amazon, Naver is betting it can rebuild Poshmark, which has 130 million active users, with the same technology that made Naver dominant in its own country.

It may also help breathe new life into the resale market. Analysts think the resale fashion market still has room to grow in the United States, with revenue expected to increase 26 percent to $36.3 billion by 2028, according to the retail consultancy firm Coresight Research.

New legislation in California could help. The law, passed last year, requires brands and retailers that operate in the state and generate at least $1 million to set up a “producer responsibility organization” to collect and then reuse, repair or recycle its products. Resale platforms like ThredUp and Poshmark could be in a position to help brands carry out that mandate.

At the moment, though, Naver’s focus for Poshmark is more basic: Make it a better place to sell and shop. The company has the “operating know-how” to do that, said Philip Lee, a founder of the media outlet The Pickool, which covers both South Korean and U.S. tech companies.

“They’re trying to renovate Poshmark and then expand the market share,” he said.

A Marriage of Search and Commerce

Poshmark, which is based in Redwood City, Calif., was founded in 2011 by Manish Chandra, an entrepreneur and former tech executive, and three others. In trying to expand, Poshmark faced a problem common to resellers: Capturing the excitement of the secondhand-shopping treasure hunt while not frustrating buyers with an endless scroll. The company knew it needed better search, as well as interactive elements that gave people more reasons to come beyond paying $19 for a J. Crew sweater.

For its part, Naver was looking for ways to push beyond South Korea, where its commerce and search businesses were already mature. The growing online resale market in the United States presented an opportunity, and also gave the company access to the largest consumer market in the world.

“Commerce is a big growth engine for us,” Namsun Kim, Naver’s chief financial officer, said. And the peer-to-peer sector, where users sell to one another, was still in its infancy, with room to expand. But, Mr. Kim added, “it’s a more challenging segment, and that’s why it’s harder for a lot of the larger players to enter.”

There are two common business models for resale: peer-to-peer and consignment. With consignment, a platform collects and redistributes physical goods. Poshmark uses the peer-to-peer model, which relies on scores of people — many of them novices — haggling over prices and then mailing items to one another. This decentralization can be a headache for brands, which like to maintain a certain level of control of their products. And platforms like Poshmark must make buyers comfortable with trusting the sellers on their site.

Before the Naver purchase, it was difficult to push through needed technological changes, said Vanessa Wong, the vice president of product at Poshmark.

“I would always talk to my engineers and ask, ‘What if we do this or do that?’ They’re like, ‘That’s hard. The effort’s really high,’” Ms. Wong said.

Naver’s purchase offered both the investment and the expertise to pull off the changes. Founded in 1999, the company is everywhere in South Korea.

“We are not just a simple search technology or A.I. service,” said Soo-yeon Choi, the chief executive of Naver, whose headquarters are near Seoul. The company, she said, “alleviates the frustrations of people, which is what is needed to help growth.”

Search built Naver “into the massive power that they are in Korea,” said Mr. Chandra, who stayed on as chief executive after Naver’s purchase. It was the top priority when the company bought Poshmark.

Several new elements for users and sellers have been introduced. With a tool called Posh Lens, users can take a photo of an item and, using Naver’s machine-learning technology, the site populates listings that are the same or similar to the shoe or tank top that they’re searching for. A paid ad feature for sellers called “Promoted Closet,” pushes listings higher on customer feeds.

Poshmark also introduced live shows, some of which are themed, to draw in the TikTok generation and increase engagement. One party auctioned off clothing previously worn by South Korean celebrities, a connection that was made with the help of Naver.

Still, the resale market is going through growing pains and has not quite found its footing since the height of the pandemic. It’s not clear whether the changes taking place at Poshmark will be enough. In May, Mr. Kim, Naver’s finance chief, said in an earnings call that Poshmark’s profitability was improving, but by November, the company was cautioning that growth had slowed because of weakness in the peer-to-peer resale market in North America.

Missteps and Reinvention

The company has already done some backpedaling on unpopular decisions.

In October, Poshmark introduced a new fee structure, which increased costs for buyers. Sellers, fearing that higher costs would make consumers bolt, revolted. Within weeks, the company scrapped the new fee structure.

And there are still user headaches: tags and keywords that help users find what they’re looking for can be miscategorized. Sellers sometimes tag their products incorrectly to get more eyeballs on their less popular products. (Hard-to-offload Amazon leggings, for example, may be listed as Free People apparel.)

The company is beta testing changes with its frequent sellers — people like Alex Mahl, who sells thousands of dollars in apparel on the site each year. And within dedicated Facebook groups related to Poshmark, there’s a lot of chatter about the changes that sellers and buyers would still like to see.

“The only way for it to do well is there’s going to be constant changes,” Ms. Mahl said about the tweaks on Poshmark. “If you were just on an app that never changed — one, it would be boring, and two, the opportunity to just do better wouldn’t be there.”

One recent morning, Ms. Eager, the seller who joined Poshmark back in college, was pleasantly surprised to find that the app had some new features she actually liked. She snapped a photo of her Aerie gray tank top with Posh Lens. Within seconds, the app populated listings of similar products. It was so much better than conjuring up the adjectives needed to describe it.

“Love it,” Ms. Eager exclaimed.

Business

When receipts of home renovations are lost, is the tax break gone too?

Dear Liz: I have sold my family home recently after almost 50 years. I had done lots of improvements throughout those years. Due to a fire 15 years ago, all the documentation for these improvements has been destroyed. How do I document the improvements for the capital gains tax calculation?

Answer: As you probably know, you can exclude $250,000 of capital gains from the sale of a principal residence as long as you own and live in the home at least two of the previous five years. The exclusion is $500,000 for a couple.

Once upon a time, that meant few homeowners had to worry about capital gains taxes on the sale of their home. But the exclusion amounts haven’t changed since they were created in 1997, even as home values have soared. Qualifying home improvements can be used to increase your tax basis in the home and thus decrease your tax bill, but the IRS probably will demand proof of those changes should you be audited.

You could ask any contractors you used who are still in business if they will provide written verification of the work they performed, suggests Mark Luscombe, principal analyst for Wolters Kluwer Tax & Accounting. You also could check your home’s history with your property tax assessor to see if its assessment was adjusted to reflect any of the improvements.

At a minimum, prepare a list from memory of the improvements you made, including the year and the approximate cost. If you don’t have pictures of the house reflecting the changes, perhaps friends and relatives might. This won’t be the best evidence, Luscombe concedes, but it might get the IRS to accept at least some increase in your tax basis.

If you’re a widow or widower, there’s another tax break you should know about. At least part of your home would have gotten a step-up in tax basis if you were married and your co-owner spouse died. In most states, the half owned by the deceased spouse would get a new tax basis reflecting the home’s current market value. In community property states such as California, both halves of the house get this step-up. A tax pro can provide more details.

Other homeowners should take note of the importance of keeping good digital records. While documents may not be lost in a fire, they may be misplaced, accidentally discarded or (in the case of receipts) so faded they’re illegible. To make sure documents are available when you need them, consider scanning or taking photographs of your records and keeping multiple copies, such as one set in your computer and another in a secure cloud account.

When an employee is misclassified as contractor

Dear Liz: A parent recently wrote to you about a son who was being paid as a contractor. I know someone else who got a job that did not “take out taxes from his paycheck.” Such workers believe they are pocketing more money, but unfortunately, too many do not know about the nature of withholding. They only learn if they choose to file for their expected refund, but instead discover an exorbitant tax liability that a paycheck-to-paycheck worker cannot pay.

The sad fact is that many of these employers improperly classify their workers, who are truly employees, as independent contractors! And they do this to avoid paying their own portion of Social Security and unemployment taxes and also workers compensation insurance.

If workers believe that they have been misclassified (the IRS website provides all criteria), they can file IRS Form SS-8 and Form 8919, which will allow them to pay only their allocated half of their Social Security taxes. Hopefully the IRS will then contact these employers to correct their wrong classifications. And finally, it should be a law that, when hired, all true independent contractors should be given a clear form (not fine print on their employment agreements) that informs them of their status and the need to make estimated tax payments.

Answer: A big factor in determining whether a worker is an employee or contractor is control. Who controls what the worker does and how the worker does the job? The more control that’s in the employer’s hands, the more likely the worker is an employee.

However, the IRS notes that there are no hard and fast rules and that “factors which are relevant in one situation may not be relevant in another.”

The form you mentioned, IRS Form SS-8, also can be filed by any employer unsure if a worker is properly classified.

Liz Weston, Certified Financial Planner®, is a personal finance columnist. Questions may be sent to her at 3940 Laurel Canyon, No. 238, Studio City, CA 91604, or by using the “Contact” form at asklizweston.com.

Business

Inside Elon Musk’s Plan for DOGE to Slash Government Costs

An unpaid group of billionaires, tech executives and some disciples of Peter Thiel, a powerful Republican donor, are preparing to take up unofficial positions in the U.S. government in the name of cost-cutting.

As President-elect Donald J. Trump’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency girds for battle against “wasteful” spending, it is preparing to dispatch individuals with ties to its co-leaders, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, to agencies across the federal government.

After Inauguration Day, the group of Silicon Valley-inflected, wide-eyed recruits will be deployed to Washington’s alphabet soup of agencies. The goal is for most major agencies to eventually have two DOGE representatives as they seek to cut costs like Mr. Musk did at X, his social media platform.

This story is based on interviews with roughly a dozen people who have insight into DOGE’s operations. They spoke to The Times on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

On the eve of Mr. Trump’s presidency, the structure of DOGE is still amorphous and closely held. People involved in the operation say that secrecy and avoiding leaks is paramount, and much of its communication is conducted on Signal, the encrypted messaging app.

Mr. Trump has said the effort would drive “drastic change,” and that the entity would provide outside advice on how to cut wasteful spending. DOGE itself will have no power to cut spending — that authority rests with Congress. Instead, it is expected to provide recommendations for programs and other areas to cut.

But parts of the operation are becoming clear: Many of the executives involved are expecting to do six-month voluntary stints inside the federal government before returning to their high-paying jobs. Mr. Musk has said they will not be paid — a nonstarter for some originally interested tech executives — and have been asked by him to work 80-hour weeks. Some, including possibly Mr. Musk, will be so-called special government employees, a specific category of temporary workers who can only work for the federal government for 130 days or less in a 365-day period.

The representatives will largely be stationed inside federal agencies. After some consideration by top officials, DOGE itself is now unlikely to incorporate as an organized outside entity or nonprofit. Instead, it is likely to exist as more of a brand for an interlinked group of aspirational leaders who are on joint group chats and share a loyalty to Mr. Musk or Mr. Ramaswamy.

“The cynics among us will say, ‘Oh, it’s naïve billionaires stepping into the fray.’ But the other side will say this is a service to the nation that we saw more typically around the founding of the nation,” said Trevor Traina, an entrepreneur who worked in the first Trump administration with associates who have considered joining DOGE.

“The friends I know have huge lives,” Mr. Traina said, “and they’re agreeing to work for free for six months, and leave their families and roll up their sleeves in an attempt to really turn things around. You can view it either way.”

DOGE leaders have told others that the minority of people not detailed to agencies would be housed within the Executive Office of the President at the U.S. Digital Service, which was created in 2014 by former President Barack Obama to “change our government’s approach to technology.”

DOGE is also expected to have an office in the Office of Management and Budget, and officials have also considered forming a think tank outside the government in the future.

Mr. Musk’s friends have been intimately involved in choosing people who are set to be deployed to various agencies. Those who have conducted interviews for DOGE include the Silicon Valley investors Marc Andreessen, Shaun Maguire, Baris Akis and others who have a personal connection to Mr. Musk. Some who have received the Thiel Fellowship, a prestigious grant funded by Mr. Thiel given to those who promise to skip or drop out of college to become entrepreneurs, are involved with programming and operations for DOGE. Brokering an introduction to Mr. Musk or Mr. Ramaswamy, or their inner circles, has been a key way for leaders to be picked for deployment.

That is how the co-founder of Loom, Vinay Hiremath, said he became involved in DOGE in a rare public statement from someone who worked with the entity. In a post this month on his personal blog, Mr. Hiremath described the work that DOGE employees have been doing before he decided against moving to Washington to join the entity.

“After 8 calls with people who all talked fast and sounded very smart, I was added to a number of Signal groups and immediately put to work,” he wrote. “The next 4 weeks of my life consisted of 100s of calls recruiting the smartest people I’ve ever talked to, working on various projects I’m definitely not able to talk about, and learning how completely dysfunctional the government was. It was a blast.”

These recruits are assigned to specific agencies where they are thought to have expertise. Some other DOGE enrollees have come to the attention of Mr. Musk and Mr. Ramaswamy through X. In recent weeks, DOGE’s account on X has posted requests to recruit a “very small number” of full-time salaried positions for engineers and back-office functions like human resources.

The DOGE team, including those paid engineers, is largely working out of a glass building in SpaceX’s downtown office located a few blocks from the White House. Some people close to Mr. Ramaswamy and Mr. Musk hope that these DOGE engineers can use artificial intelligence to find cost-cutting opportunities.

The broader effort is being run by two people with starkly different backgrounds: One is Brad Smith, a health care entrepreneur and former top health official in Mr. Trump’s first White House who is close with Jared Kushner, Mr. Trump’s son-in-law. Mr. Smith has effectively been running DOGE during the transition period, with a particular focus on recruiting, especially for the workers who will be embedded at the agencies.

Mr. Smith has been working closely with Steve Davis, a collaborator of Mr. Musk’s for two decades who is widely seen as working as Mr. Musk’s proxy on all things. Mr. Davis has joined Mr. Musk as he calls experts with questions about the federal budget, for instance.

Other people involved include Matt Luby, Mr. Ramaswamy’s chief of staff and childhood friend; Joanna Wischer, a Trump campaign official; and Rachel Riley, a McKinsey partner who works closely with Mr. Smith.

Mr. Musk’s personal counsel — Chris Gober — and Mr. Ramaswamy’s personal lawyer — Steve Roberts — have been exploring various legal issues regarding the structure of DOGE. James Burnham, a former Justice Department official, is also helping DOGE with legal matters. Bill McGinley, Mr. Trump’s initial pick for White House counsel who was instead named as legal counsel for DOGE, has played a more minimal role.

“DOGE will be a cornerstone of the new administration, helping President Trump deliver his vision of a new golden era,” said James Fishback, the founder of Azoria, an investment firm, and confidant of Mr. Ramaswamy who will be providing outside advice for DOGE.

Despite all this firepower, many budget experts have been deeply skeptical about the effort and its cost-cutting ambitions. Mr. Musk initially said the effort could result in “at least $2 trillion” in cuts from the $6.75 trillion federal budget. But budget experts say that goal would be difficult to achieve without slashing popular programs like Social Security and Medicare, which Mr. Trump has promised not to cut.

Both Mr. Musk and Mr. Ramaswamy have also recast what success might mean. Mr. Ramaswamy emphasized DOGE-led deregulation on X last month, saying that removing regulations could stimulate the economy and that “the success of DOGE can’t be measured through deficit reduction alone.”

And in an interview last week with Mark Penn, the chairman and chief executive of Stagwell, a marketing company, Mr. Musk downplayed the total potential savings.

“We’ll try for $2 trillion — I think that’s like the best-case outcome,” Mr. Musk said. “You kind of have to have some overage. I think if we try for two trillion, we’ve got a good shot at getting one.”

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCarter's judicial picks reshaped the federal bench across the country

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSouth Korea extends Boeing 737-800 inspections as Jeju Air wreckage lifted

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg) Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoMeta is highlighting a splintering global approach to online speech

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSeeking to heal the country, Jimmy Carter pardoned men who evaded the Vietnam War draft

-

Science1 day ago

Science1 day agoMetro will offer free rides in L.A. through Sunday due to fires

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump Has Reeled in More Than $200 Million Since Election Day