World

French police: Why their protest measures are so controversial

French police reject accusations of violence but protesters, journalists and experts decry the repeated use of weapons and restrictive preventative measures.

French police are some of the most heavily armed in Europe, drawing from an arsenal holding sting-ball grenades, GM2L tear gas and flash-balls—some classified as war materials—to ‘maintain order’ in nationwide protests. But researchers argue that excessive police force is effectively executed by design in a system that is resistant to change.

Human rights organisations, including the UN, Council of Europe and Amnesty International have sounded alarms on the force’s violent tactics, particularly during pension reform protests this year.

“There is, effectively, a regime of police violence in France,” Mathieu Rigouste, researcher in social sciences and author of La Domination Policière, said. “Not only in France, obviously… and this is characterised again by the retirement protest movement, by a general use of massive brutality, heavy use of poisonous gas and mutilating weapons.”

Adjacent EU countries have implemented de-escalation policies and operate with theoretically higher accountability and less weaponry, according to Sebastian Roché, a researcher specialising in policing at the National Center for Scientific Research.

“There’s a big difference between the French approach and the approaches of the big European neighbours that also have problems with protests,” he said.

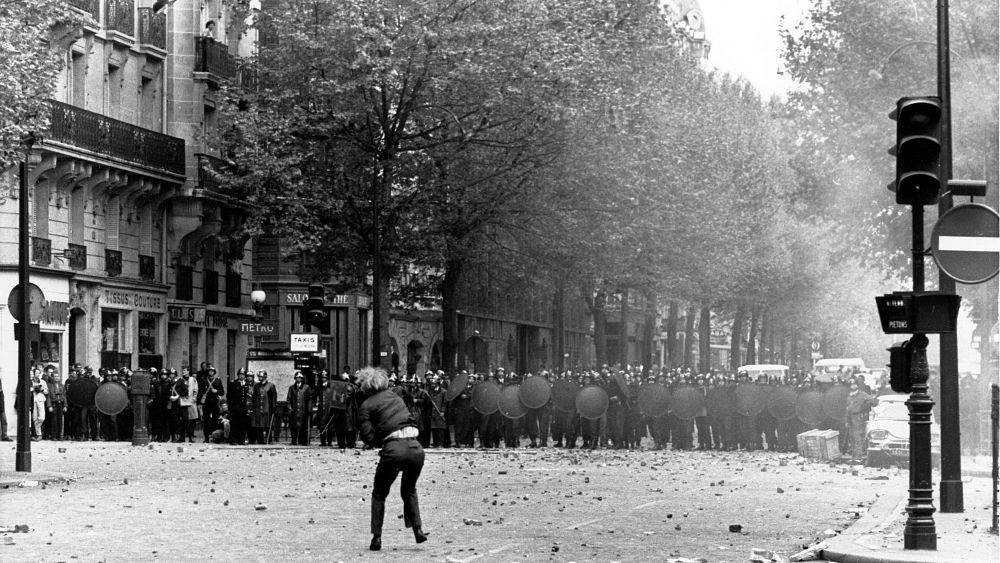

Experts cite colonialism, the aftermath of the 1968 protests and a general superiority complex as some of the influential factors on French policing and resistance to reform.

Flash-balls, grenades, water cannons, GM2L tear gas, batons

French police have flash-balls, grenades and grenade launchers, water cannons, GM2L tear gas, batons and tonfas, quads and firearms at their disposal during protests, which are responsible for almost all of the injuries caused on the ground, according to Roché.

From the flash-ball alone—which launches a 28-gram rubber bullet at 350 km/h—there have been 29 permanent mutilations and 620 people hit since November 2018, the start of the yellow vests movement, according to violencespoliciers.fr. The site notes that 28% of the victims were hit in the head.

Though France isn’t the only country in Europe that’s equipped with these arms, it’s an anomaly in comparison to other long-standing European democracies. Police forces in Greece and certain regions of Spain carry similar weaponry, according to Roché. But in comparison to the UK, Germany and the Scandinavian countries—who also use arms to disperse protesters—the French arsenal is even more expansive.

“The Germans use water cannons from big vehicles that project water onto protesters to push them back…this is their principal instrument,” Roché said. “The English don’t have water cannons—they judge that they’re impractical, dangerous and expensive… same for the Scandinavian countries, they don’t have grenades and rubber bullets.”

‘Tear gas was used in Algeria before being used in May 1968 in France’

Researchers argue French policing tactics today have links to colonialism and the aftermath of the May 1968 protests. The arms deployed in French protests were ‘tested’ during colonial rule.

“Tear gas was used in Algeria before being used in May 1968 in France,” Roché said.

Rigouste argues colonialism has a pervasive impact on French policing beyond its arsenal, noting that the current model is more media and police-centric, while the previous was more militarised.

“These management models, these regimes of violence, [were] imported and translated, remodelled in France itself… it’s not exactly the same model, but there are links, there’s a continuity,” he said.

After the May 1968 protests, the French government formed the ‘Voltigeurs,’ a specialised police force on motorcycles that many cite as the precursor to today’s Brav-M, the motorised unit accused of excessive violence against protesters.

“In 1968, the permanent war market that was essential to contemporary capitalism opened up to a new market, to regenerate capitalism in the market of interior war—the market of security,” Rigouste said.

‘There is no legal definition of order’

A key difference between France and countries like Germany and the UK is that while the latter theoretically follow principles of de-escalation at protests, the French approach adapts to the violence level of the protesters to “maintain order,” according to Roché.

But this could be a grey zone by definition. Police operate under the National Schema of Maintaining Public Order. But “order” is a subjective term, leaving room for interpretation.

“There is no legal definition of order,” Roché said.

The protests this spring sparked concern as to whether the French police actually follow their own rules.

Police are obligated to facilitate the work of journalists during protests, and journalists should even benefit from added protection, according to the public order schema.

“What we’ve seen is the contrary— journalists that filmed were threatened sometimes… hit to the ground, their material was damaged or broken by the police,” Roché said.

Rémy Buisine, a journalist, brought attention to this issue when he was struck by a truncheon while lying on the ground, shortly after he had been hit by a sting-ball grenade while filming an Instagram live for Brut.

“What’s really problematic is that we have a usage of force, even violence, brutality… and it’s carried out before there’s trouble,” Vincent Victor, co-founder of violencespoliciers.fr, said. “This is completely illegal… in these conditions, the usage of force is disproportionate compared to the situation.”

But Eric Henry, National Delegate for the union Alliance Police Nationale, maintains that French police always operate within their legal bounds during protests.

“There’s only legitimate force, strictly necessary, the force that is authorised by the law, so the police can defend themselves or to protect [peaceful demonstrators],” he told Euronews. “Police violence doesn’t exist.”

‘The arrests are preventative’

Preventative arrests are another issue that sparks concern, according to Roché and Rigouste.

Police carry out pre-checks to look for items like goggles or gas masks that could indicate resistance to tear gas, for example. There are groups — like Black-Blocs — that attend protests specifically to provoke violence, and the schema does account for taking an anticipatory role in preventing this.

During May Day this year, 108 police officers were injured, according to the Interior Ministry. But assumptions some attend to incite violence are not grounds for taking people into custody, according to Rigouste, referring to arrests in Sainte-Soline this spring.

“The arrests are preventive, meaning we arrest people based on what we presume their ideas and the possibilities of taking action are,” he said.

“[The police] are there to help demonstrators get from Point A to Point B… to allow people to protest safely, to preserve the freedom to demonstrate– that’s their role,” Céline Verzeletti, Secretary General at the CGT union said. “But today, we have the impression that they’re there to arrest protesters, or threaten protesters.”

Roché notes the police have also used intimidation tactics to deter people from attending protests in the first place, despite protesting being considered a fundamental right in France.

“Throughout history, when [the government] was confronted with revolts, with uprisings, when they’re threatened by popular revolt, they step up their regime of repression, and they militarise more and more,” Rigouste said. “And this is something that is seen throughout history in all nation states.”

‘It’s a culture that evolves in a closed space’

In Europe, there have been concerted efforts to evolve policing tactics. In 2010, twelve countries—including Sweden, Germany, the UK, Denmark and Austria—participated in the EU-backed GODIAC project (“Good practice for dialogue and communication as strategic principles for policing political manifestations in Europe”) to promote communication during protests.

GODIAC initiated field study groups, workshops and seminars over a three-year period. The reports would then be used for future police training. France did not participate, but it has now included a section on communication in the schema.

Roché believes the French police force suffers from a superiority complex.

“If you listen to the heads of the police and politicians… they think they’re the best in the world,” he said. “Since they’re the best in the world, they have nothing to learn from others.”

This spring, in the midst of nationwide retirement protests — and videos of police and protester clashes circulating through social media— Darmanin said point-blank on RTL radio that “there is no police violence”.

Roché argues a centralised structure, compared to other countries in the EU, could bolster a superior stance.

“So it’s a culture that evolves in a closed space,” he said. “It’s more difficult to reform it.”

World

Video: South Korea’s Political Instability Deepens With New Impeachment

Lawmakers from South Korea’s governing party protested on Friday against a vote to impeach the country’s acting president, Han Duck-soo. The motion, which passed 192-0, came less than two weeks after President Yoon Suk Yeol was also ousted by the opposition in the National Assembly.

World

Man on vacation with family goes overboard on Norwegian cruise ship in Bahamas

The frantic search for a Norwegian Cruise Line passenger who went overboard has been called off.

A spokesperson for the cruise line confirmed to Fox News Digital that the 51-year-old went overboard from Norwegian Cruise Line’s Norwegian Epic late Thursday afternoon.

The incident was first noted at approximately 3 p.m. as Norwegian Epic was sailing from Ocho Rios, Jamaica en route to Great Stirrup Cay in the Bahamas.

The passenger was on the cruise with his family, the spokesperson said. The cruise left from Port Canaveral, Florida on Saturday, Dec. 21 and was a seven-night Western Caribbean voyage.

DISNEY CRUISE LINE NO LONGER ACCEPTING PHOTOCOPIES OF GUEST BIRTH CERTIFICATES

The cruise liner Norwegian Jewel built at the ship yard Meyer in Papenburg, northern Germany, goes down the river Ems. (AP Photo/Joerg Sarbach, File)

The cruise line said that authorities were quickly notified and search and rescue efforts were immediately implemented.

SOCIAL MEDIA USERS GET DRAMATIC AFTER CARNIVAL CRUISE SHIP HITS ICE IN ALASKA: ‘TITANIC MOMENT’

“After an extensive search that was unfortunately unsuccessful, the ship was released by the authorities to continue its voyage,” the spokesperson said.

The Norwegian Epic, which was built in 2010 and refurbished in 2020, has 19 decks. (Norwegian Cruise Line)

Norwegian Cruise Line said the passenger’s loved ones on board were “being attended to and supported during this very challenging situation.”

“Our thoughts and prayers are with his loved ones during this difficult time,” the spokesperson added.

The Norwegian Epic, which was built in 2010 and refurbished in 2020, has 19 decks. It can accommodate 4,070 passengers with double occupancy of its cabins and has 1,724 crew members.

It was not immediately clear what caused the man to go overboard. The man has not been identified.

World

Olive oil, milk and cereals: How did food prices fluctuate in 2024?

After food prices soared in 2021 and 2022, over five essential food products saw price drops in 2024, including milk and cereals.

In 2024, agricultural prices in the European Union saw a modest decline, falling by 2% compared to 2023.

This price decline followed sharp increases in 2021 and 2022 that occurred due to the COVID-19 pandemic, extreme weather conditions and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Despite a surge in olive oil prices in 2024, the prices of cereals dropped by 15%, eggs by 8%, and vegetables and horticultural products declined by 2%.

The price of pigs and poultry also shrank by 7% and 8%, respectively.

According to Eurostat figures, milk prices decreased in 16 EU countries in 2024.

The sharpest decline was recorded in Finland with a 12% drop in prices, followed by Portugal with 10% and Spain with 8%.

By contrast, the sharpest increase was in Ireland with a 15% rise in prices, followed by Lithuania with 11% and Latvia with 10%.

In terms of production, the cost of seeds and veterinary services rose by 3%.

However, prices for fertilisers and soil improvers plummeted by 18%, food for animals by 11%, and plant protection products and pesticides by 2%.

Commission measures between farmers and buyers

After a year in which farmers have protested regularly, the EU Commission has presented an initiative to ensure they receive fair compensation and are no longer forced to sell products below production costs.

The proposed measures include mandatory written contracts that require buyers to clearly outline key terms such as price, quantity, and delivery timelines, taking into account market conditions and cost fluctuations.

The package also introduces a regulation to enhance enforcement of the Unfair Trading Practices (UTPs) Directive, which was adopted five years ago but remains largely unimplemented.

Video editor • Mert Can Yilmaz

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png) Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoGoogle’s counteroffer to the government trying to break it up is unbundling Android apps

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNovo Nordisk shares tumble as weight-loss drug trial data disappoints

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoIllegal immigrant sexually abused child in the U.S. after being removed from the country five times

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week ago'It's a little holiday gift': Inside the Weeknd's free Santa Monica show for his biggest fans

-

Lifestyle1 week ago

Lifestyle1 week agoThink you can't dance? Get up and try these tips in our comic. We dare you!

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png) Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoThere’s a reason Metaphor: ReFantanzio’s battle music sounds as cool as it does

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoFox News AI Newsletter: OpenAI responds to Elon Musk's lawsuit

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoFrance’s new premier selects Eric Lombard as finance minister