Colorado

Opinion: The surprise release of wolves near my ranching town has eroded rancher’s trust

At 5:20 p.m. on Dec. 18, I received an email from the Colorado Parks and Wildlife. I signed up for the mailing list for wolf reintroduction updates after Proposition 114 was passed because I knew this decision could determine the viability of my future in ranching.

As I opened the email, I expected another fact sheet of advice on how to deal with an encounter; I was floored by what I read. Five wolves had been released in Radium, a small town that I was once assured was a doable day-long horse ride from my home.

Disbelief is what first struck me, and now writing this, a pit in my stomach that comes from some combination of fear, stress, and anxiety. I hear my neighbors and friends demanding that someone, really anyone, hear their side of the story and try to understand how this action has devastated their futures as livestock producers.

To be a rancher is to raise an animal or a product that you are proud to stand behind and say “This is the product of my family’s hard work.” This means that the livestock’s health and safety come above everything. It means laying awake at 3 a.m. thinking about how an early frost will affect the health of cattle.

Ranching is kids learning from their parents, raising their 4-H animals themselves, and taking pride in feeding and checking them morning and evening. It is going through livestock every 3 hours around the clock during calving and lambing, and staying up to make sure everything is going smoothly. At gathering time, it is checking ‘just one more spot’ as the light is quickly fading and returning home well after dark, knowing that at first light they will be back out searching.

I have spent the last year investigating and researching policies reflective of the urbanization of Colorado and the effects that it has on ranchers. Notably, the importance of trust in agents of change and the growing urban-rural divide of Colorado.

These two notes I made from the works I studied are imperative to the conversation when looking forward to a Colorado landscape inclusive of wolves. A 2022 paper by Shelby Carlson and other researchers in Conservation Biology emphasizes that acceptance of wildlife, specifically carnivore, risks is dependent on trust in the agency managing those risks. Meanwhile, the Craig Daily Press reported in March that the 10-J ruling, in effect Dec. 8, is seen as “an essential tool for [ranchers] dealing with an already bad situation” and supports Carlson’s research. By implementing this rule, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Colorado Parks and Wildlife are working to build trust with ranchers.

But the Craig Daily Press coverage of a local public comments session details the fear, helplessness, stress, and anger of attendants.

These feelings from early 2023 are echoed as wolves enter the landscape, with local ranchers feeling blindsided by agents of change without warning of the introduction to their backyard. While Radium is within the area that the CPW announced as a favorable environment for wolf introduction, there hasn’t been meaningful contact from the organization to livestock owners in the area since.

Trust between the CPW and ranchers has further been broken as it was uncovered by 9NEWS that three of the five wolves released on Dec. 18 came from packs depredating on livestock in Oregon. In an interview with 9NEWS on Nov. 28, a CPW specifically said their organization would not translocate wolves from problem packs.

Two of the wolves are from a pack that in August the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife authorized the killing of four wolves in the chronically depredating Five Points Pack. On Dec. 22, CPW announced that they had released 10 wolves total, with the following five not announced publicly. Looking at the list of released wolves and the packs they came from, eight of the 10 are definitively from packs that have engaged in livestock depredation.

As far as building relationships with the ranching community, this action immensely harms any sort of trust that the CPW could have hoped to build with local ranchers.

The urban-rural divide of Colorado boils down to a difference in experience and lifestyle between the citizens of the state. The physical separation between the two population types, rural and urban, mirrors the opposing voting tendencies, creating a natural dichotomy. This can further be connected to Carolan’s later research highlighting the feeling of rural communities that they are being left behind as they have less political capital (Carolan 2020).

The social, geographical, and political divide of Colorado’s citizens comes from lived experiences and shared worldviews with their respective communities. The trouble comes from the division of these groups, and the actions taken that affect the livelihoods of entire communities. This division is only bridged through sharing experiences and listening with intention.

So with the wolves now here in Colorado, what are ranchers feeling?

Sadness, that as stewards of the land, they will have to see the wildlife and their livestock not only face the hardships of a Colorado winter but now also change their ingrained herd patterns and habits in response to wolf predation.

Helplessness, as many parents explain to their children that they cannot do their chores alone anymore because as parents they fear for their safety with wolves in the area. The conversations are tough especially around not being able to defend their livestock, and having no meaningful response to the endless “but why?” Followed by questions about whether their 4-H steer, or lamb, or pig will be OK.

Worry, as in the days following the release, helicopters and planes circle areas that they only check in the fall and spring for wildlife counts, and the worry of not knowing what is happening right in their own backyards.

Anger, at choices made by populations whose livelihoods will be unaffected. Anger that this particular choice may be the breaking point for a family ranch already burdened by the strains of operating a livestock business. Anger that agents of change are not holding their word and introducing real danger to livestock producers.

Fear for family, livestock, and the future. Fear that two of the wolves released already know how to attack livestock, and may target local ranches rather than hunting wildlife. Fear that the future holds impending danger for the viability of old and young ranchers alike in Colorado.

The damage to the livelihoods of many ranchers in Colorado was done as those five wolves stepped into the landscape. Now, it is imperative to work collectively to understand to what extent this choice will affect the rural population and to support the community with the most to lose.

Skylar Fischer is a young rancher working in Toponas, Colorado.

Sign up for Sound Off to get a weekly roundup of our columns, editorials and more.

To send a letter to the editor about this article, submit online or check out our

Colorado

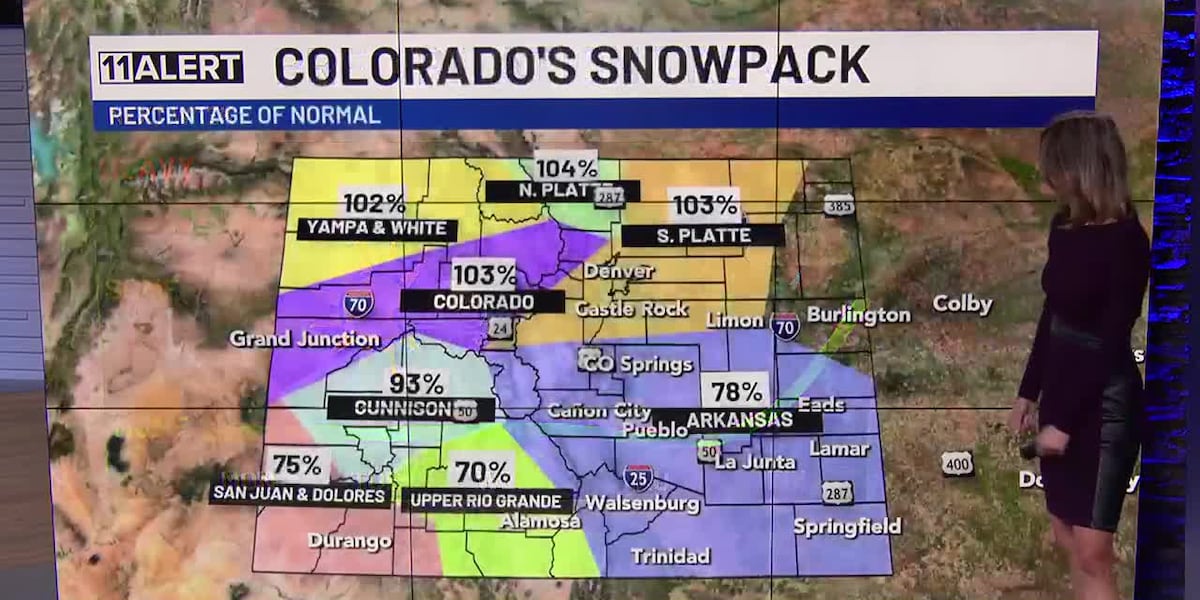

Big warming trend ahead for southern Colorado

- Highs in the 60s and 70s

- Staying breezy

- Dry trend continues

EARLY NEXT WEEK: Temperatures will begin to climb to reach 60s and 70s for most. Expect lots of sunshine with dry time continuing too. Wind gusts will be up to 25 MPH.

Download the KKTV 11 Alert Weather App Here:

LATER IN THE WEEK: Southern Colorado stays breezy with gusts continuing to stay elevated. Temperatures stay 10 to 15 degrees above seasonal averages, so high fire danger is likely to return.

THE WEEKEND: We return to seasonal temperatures on Saturday with rain chances too. Sunday is expected to remain fairly cool too.

Copyright 2025 KKTV. All rights reserved.

Colorado

Maryland and Colorado State play in second round of NCAA Tournament – WTOP News

No. 11 Maryland and Colorado State square off in the NCAA Tournament second round.

Colorado State Rams (26-9, 19-4 MWC) vs. Maryland Terrapins (26-8, 15-7 Big Ten)

Seattle; Sunday, 7:10 p.m. EDT

BETMGM SPORTSBOOK LINE: Terrapins -7.5; over/under is 142.5

BOTTOM LINE: No. 11 Maryland and Colorado State square off in the NCAA Tournament second round.

The Terrapins’ record in Big Ten play is 15-7, and their record is 11-1 against non-conference opponents. Maryland ranks seventh in the Big Ten with 9.1 offensive rebounds per game led by Julian Reese averaging 3.0.

The Rams are 19-4 against MWC teams. Colorado State scores 75.3 points and has outscored opponents by 8.1 points per game.

Maryland averages 81.6 points, 14.4 more per game than the 67.2 Colorado State allows. Colorado State scores 8.8 more points per game (75.3) than Maryland allows (66.5).

TOP PERFORMERS: Ja’Kobi Gillespie is shooting 41.0% from beyond the arc with 2.4 made 3-pointers per game for the Terrapins, while averaging 14.7 points, 4.9 assists and 1.9 steals. Derik Queen is averaging 17.7 points and 10.7 rebounds over the past 10 games.

Nique Clifford is averaging 18.9 points, 9.7 rebounds and 4.4 assists for the Rams. Kyan Evans is averaging 13.8 points over the last 10 games.

LAST 10 GAMES: Terrapins: 8-2, averaging 78.9 points, 33.4 rebounds, 13.2 assists, 8.4 steals and 4.6 blocks per game while shooting 45.5% from the field. Their opponents have averaged 66.4 points per game.

Rams: 10-0, averaging 77.3 points, 28.5 rebounds, 15.9 assists, 6.0 steals and 2.1 blocks per game while shooting 50.8% from the field. Their opponents have averaged 63.1 points.

___

The Associated Press created this story using technology provided by Data Skrive and data from Sportradar.

Copyright

© 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, written or redistributed.

Colorado

Mild temperatures for the week ahead in Denver

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

-

Midwest1 week ago

Midwest1 week agoOhio college 'illegally forcing students' to share bathrooms with opposite sex: watchdog

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoJudges threatened with impeachment, bombs for ruling against Trump agenda

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussia, China call on US to drop Iran sanctions, restart nuclear talks

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAll illegal migrants held in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba have been sent to Louisiana

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFor Canadians Visiting Myrtle Beach, Trump Policies Make the Vibe Chillier

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoArlington National Cemetery stops highlighting some historical figures on its website

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoVance to Lead G.O.P. Fund-Raising, an Apparent First for a Vice President

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoBlack Lives Matter Plaza Is Gone. Its Erasure Feels Symbolic.