California

In California, It’s 72 With a Chance of “Weather Whiplash” | Connecting California

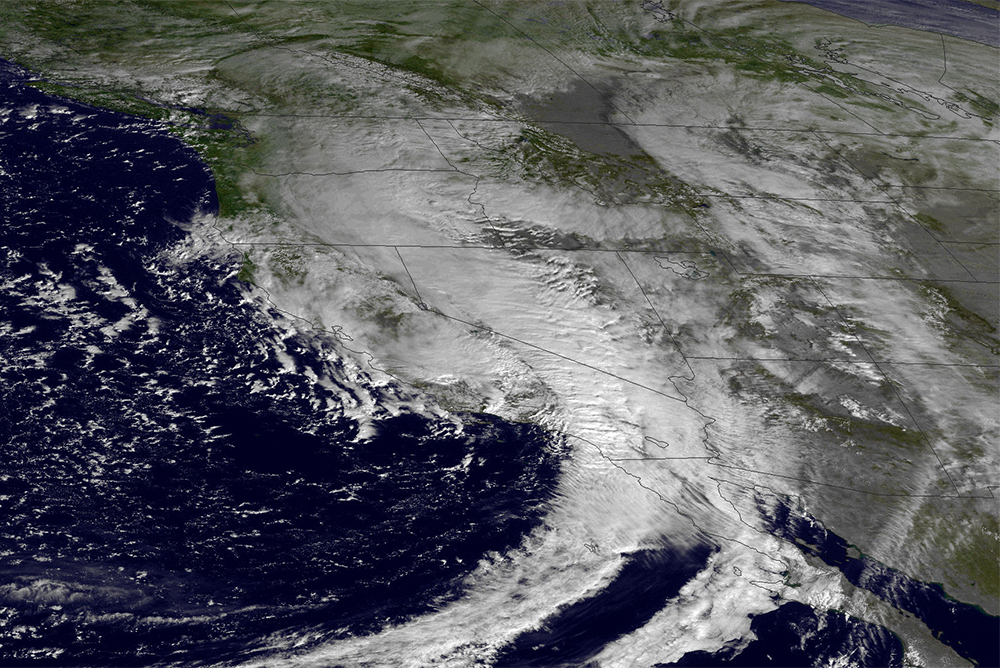

Why is it so hard to make seasonal weather predictions in California—and what’s the path to more accurate forecasts? Columnist Joe Mathews asks in the latest Connecting California. Satellite image courtesy of NOAA Photo Library/Flickr (CC BY 2.0 DEED).

California weather is harder to predict than it looks. Even Harris K. Telemacher came to learn that.

Telemacher was a Los Angeles TV weathercaster with an ocean of knowledge—he had a PhD in arts and humanities and quoted Shakespeare—but no real meteorological training. So, he assumed that California weather was predictable and decided to tape his televised forecasts weeks in advance, always promising sunny and warm days. This worked until an unexpected Pacific storm deluged the Southland during one of his pre-recorded forecasts.

Telemacher was a fictional character invented and inhabited by Steve Martin in the classic satire L.A. Story. But he embodied a real-life cliché that needs retiring.

California weather has never been as predictable as a Steve Martin gag—especially when it comes to the rain and snow of Golden State winters like this one.

In fact, no state in the lower 48 sees as much variability in its year-to-year precipitation as California. Such variability makes our weather at least as unpredictable as anything else in this volatile state. Last year, California was in the midst of the driest three-year run in recorded history when NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, published a seasonal forecast for a drier-than-average winter. Instead, we experienced one of our wettest winters ever.

Now, another winter of weather surprises has arrived, demonstrating that California desperately needs better seasonal forecasts so we can plan and protect ourselves in this era of climate change.

Seasonal forecasts are not the predictions of tomorrow’s weather that you see delivered on your TV by Telemacher and his present-day imitators. Seasonal forecasts provide a range of possible weather and climate changes for the next season on the calendar, usually about a month or so in advance. (Federal agency forecasts for winter are usually out by Halloween.) Meteorologists will tell you that while it’s impossible to tell you the weather on a particular day months in advance, they should be able to predict, broadly, how wet or dry the next season should be.

But that’s always been hard to do in California. Lately, it’s become even harder because of the state’s “weather whiplash”—the term that the Public Policy Institute of California has used in recent years to describe the seesawing we’ve seen between flood and drought.

Our current inability to predict seasonal wet conditions makes it harder to manage water supplies (we need to store more in wet winters to prepare for drier years), prepare for disasters (including unpredictable floods, like the one that recently inundated San Diego), and do long-term economic planning for agriculture, which supplies food to the entire nation.

Another winter of weather surprises has arrived, demonstrating that California desperately needs better seasonal forecasts so we can plan and protect ourselves in this era of climate change.

It’s not just winter weather that’s hard to foresee. Predicting scorching heat, as the state’s daily average maximum temperature rises by more than 4 degrees, is difficult. Impactful heat waves, called Heat Health Events, are expected to increase in frequency and duration, especially in the Central Valley and Sierra. Calling those ahead of time could be a matter of life and death.

But improving seasonal forecasts is easier said than done. Even the most advanced meteorologists have struggled with making seasonal forecasts. Indeed, recent studies, now getting attention in California policy circles, suggest that our state and its meteorologists need a better understanding of the peculiarities of the Pacific Ocean to improve their forecasts.

Making expectations about how much rain or snow is likely to fall in California depends on predicting atmospheric patterns over the northern Pacific Ocean. To do so, meteorologists have tended to look at sea surface temperatures in the South Pacific and the phenomena known as El Niño and La Ninã. Warm temperatures, or “El Niño” conditions, were believed to herald rain. Cool “La Niña” conditions were thought to signal a dry winter.

But a recent paper highlighted by PPIC, with authors from UCLA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, found that El Niño conditions don’t explain most of the variability of our weather. To cite one example, tropical sea surface temperatures and conditions were very similar in 2021–22 and 2022–23, but the first winter was dry and the second was one of the wettest in history.

“It remains elusive how predictable the year-to-year variability of CA winter precipitation is and why it is challenging to achieve skillful seasonal prediction of CA precipitation,” the paper said.

According to its authors, to arrive at more accurate seasonal forecasts, scientists need a better understanding of the ocean’s “circulation anomalies,” which are deviations in averages and expected conditions independent of El Niño. Current climate models, the paper argued, “show nearly no skill in predicting these,” which means that they have “limited predictive skill for California winter precipitation.”

The paper also argued that current climate models can’t predict patterns that stem from tropical convection (i.e. tropical clouds and thunderstorms) or the stratospheric polar vortex. This means that for better seasonal forecasts, meteorologists need a better understanding of conditions and patterns not only in the relatively nearby western Pacific but also in waters as far away as the Indian and Arctic oceans.

How do we achieve this?

One answer is to devote more time and resources to observing oceans, sea ice, and clouds—and their impacts on precipitation. Another answer is to employ better computer capacity and artificial intelligence to build better climate models. This is a planetary problem—if you want better predictions of California precipitation, you need to improve modeling and data for the climate of the whole earth.

But such improvements won’t happen fast. So, for at least a few more winters, we’re stuck with unreliable seasonal forecasts and unpredictable weather.

California

California residents flee massive wildfire sparked by burning car

Thousands of Northern California residents were forced to evacuate their homes as a massive wildfire scorched more than 250 square miles. The Park Fire, California’s largest this year, was started by a man who pushed a burning car into a gully.

California

California's billionaire utopia faces a major setback

Silicon Valley’s billionaire-backed plan to turn 60,000 acres into a utopian “city of yesterday” is officially delayed by at least two years. California Forever confirmed on July 22 that its “East Solano Plan” rezoning proposal will not appear on the region’s November election ballot. Instead, the $900 million project will first receive a full, independent environmental impact review while preparing a development agreement with local county supervisors.

Speaking with The New York Times this week, California Democratic state senator John Garamendi said, “The California Forever pipe dream is in a permanent deep freeze.”

First unveiled in August 2023 after years of stealth land purchases just outside San Francisco, organizers bill the 60,000 acre East Solano Plan as a multistep campaign to build “one of the most walkable and sustainable [towns] in the United States.” Concept art on California Forever’s website depicts idyllic pedestrian squares and solar farms, with lofty promises to bring hundreds of thousands of jobs to the area along with “novel methods of design, construction, and governance,” according to a previous profile. Overseen by former Goldman Sachs trader Jan Sramek, California Forever received financial backing from wealthy venture capitalists including LinkedIn’s co-founder Reid Hoffman and Lauren Powell Jobs, billionaire philanthropist and widow of Steve Jobs.

[ California’s billionaire utopia may not be as eco-friendly as advertised.]

But from the start, locals, environmental advocates, and politicians pushed back against the East Solano Plan. By November 2023, news broke that California Forever’s parent company previously sued a group of locals for $510 billion, citing antitrust violations after the defendants refused to sell their land (the locals later agreed to sell for $18,000 per acre). Meanwhile, state representatives voiced security concerns about the proposed city’s proximity to the nearby Travis Air Force Base.

Last month, the accredited Solano Land Trust announced its opposition to the plan, citing what it believed would be a “detrimental impact” to the region’s “water resources, air quality, traffic, farmland, and natural environment.” The land trust also alleged California Forever backers misled the public by describing much of the area as “non-prime farmland” with “low quality soils.” In reality, the Solano Land Trust explained that the “sensitive habitat… home to rare and endangered plants and animals” includes some of the state’s most water-efficient farmland.

In this week’s announcement, Sramek claims a recent poll conducted by California Forever indicated 65 percent of East Solano residents “support development of good paying jobs, more affordable homes, and clean energy,” while noting that “most voters are also asking for a full environmental impact report to be completed first.”

“The idea of building a new community and economic opportunity in eastern Solano seemed impossible on the surface,” Sramek wrote to Popular Science last year. “But after spending a lot of time learning about the community, which I now call home, I became convinced that with thoughtful design, the right long-term patient investors, and strong partnerships… we can create a new community.”

California

Tech Jobs Keep Moving Out of California. Don’t Panic Yet.

It has been a weird four years for California’s technology sector. It boomed early in the Covid-19 pandemic as people in the US and around the world geared up for remote work and directed their spending to online services (games, streaming, spin classes, etc.) they could consume without leaving home. But that rise in remote work, combined with highest-in-the-nation real estate costs, strict pandemic rules and other factors, also led to something of an exodus from the state’s coastal cities, with high-profile departures of tech leaders in 2020 and 2021 and even occasional claims that the San Francisco Bay Area’s reign as global tech capital was ending.

A few high-profile departures are still taking place, with Elon Musk announcing this month that he will be moving the headquarters of two more of his companies — X, the former Twitter, and SpaceX — from California to Texas, where he moved Tesla Inc.’s headquarters in 2021. But there have also been stories of tech leaders returning and San Francisco beginning a resurgence, with the boom in generative artificial intelligence — the biggest story in tech now — very much concentrated around the San Francisco Bay. My fellow Bloomberg Opinion columnist Conor Sen thinks it might even be a good time to buy some slightly marked-down San Francisco real estate.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoOne dead after car crashes into restaurant in Paris

-

Midwest1 week ago

Midwest1 week agoMichigan rep posts video response to Stephen Colbert's joke about his RNC speech: 'Touché'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Young Republicans on Why Their Party Isn’t Reaching Gen Z (And What They Can Do About It)

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: A new generation drives into the storm in rousing ‘Twisters’

-

Politics1 week ago

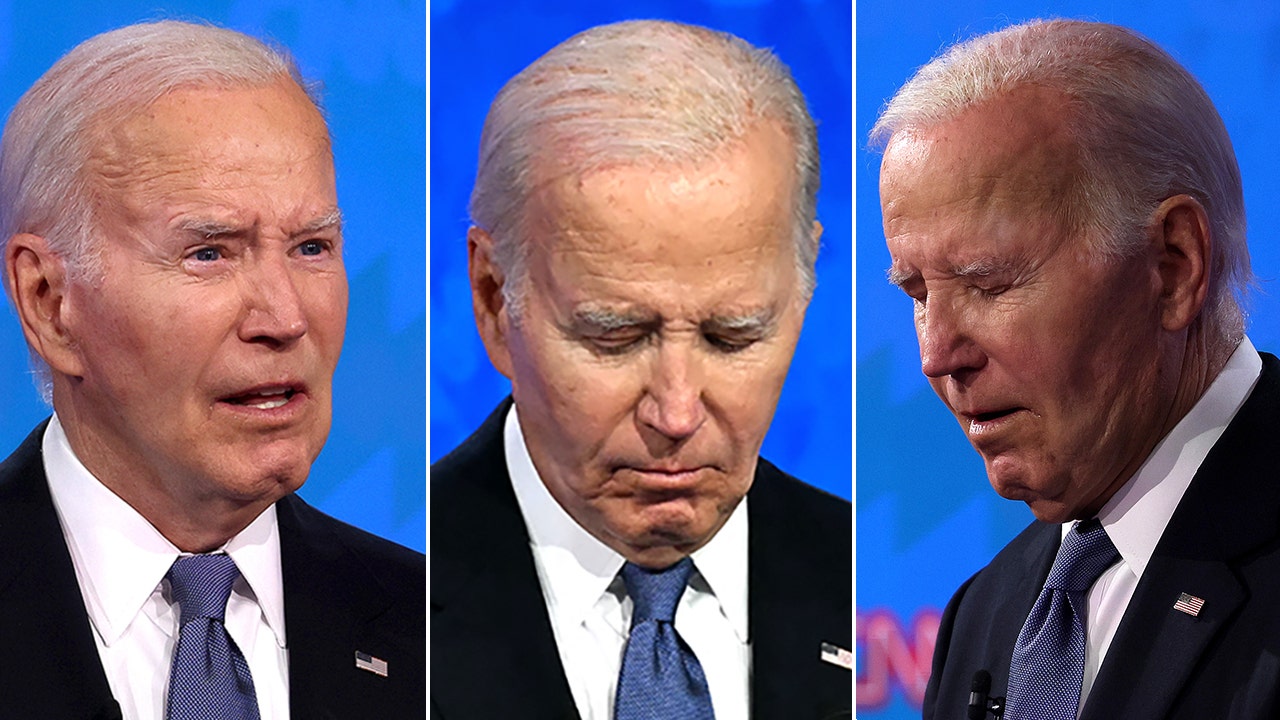

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics: The Call is Coming from Inside the House

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIn Milwaukee, Black Voters Struggle to Find a Home With Either Party

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: J.D. Vance Accepts Vice-Presidential Nomination

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrump to take RNC stage for first speech since assassination attempt