West

Caitlyn Jenner predicts a 'change' in Californians after LA fires shine ‘bright light’ on state's ‘weaknesses’

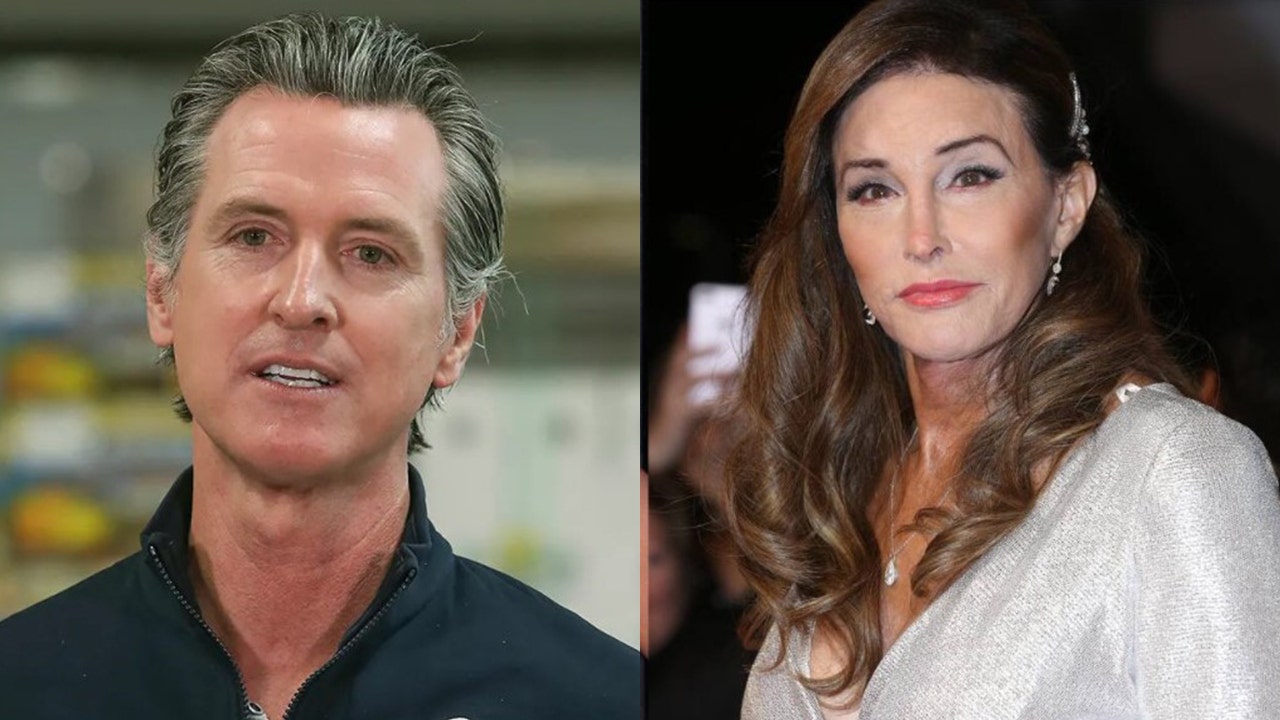

Long-time California resident and Fox News contributor Caitlyn Jenner predicts that there will be a “change” in thinking across the state after the way leadership handled the wildfires still affecting parts of Los Angeles County.

EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE WATER DROPS IN CALIFORNIA DURING WILDFIRES

Jenner, who said she has lived in California since 1973, recalled the first time she saw the state’s “Welcome to California, the Golden State” sign on Highway 82.

“Boy, have I seen this state decline over the years. We’re not gold, we’re not silver, we’re not bronze. We don’t even make the finals anymore,” Jenner told “The Story,” arguing that the state’s decline is because of the politicians running it.

The former 2021 Republican recall election candidate argued that the details emerging from how officials failed to prepare for the wildfires are going to shine a “bright light” on California’s “weaknesses.”

California Governor Gavin Newsom and Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass tour the downtown business district of Pacific Palisades as the Palisades Fire continues to burn on January 8, 2025 in Los Angeles, California (Eric Thayer/Getty Images)

“Light is good because it’s a disinfectant. I mean, we have so many issues here, mostly with the politicians,” said Jenner, likening the politician’s responses to problems like a game of “whack-a-mole.”

“You know that game when you play, when you have the mole and you have the board in front of you and the head pops up, you got a hammer, and you bang it down? And then another one comes up over here, and you bang it down,” she described.

FILMMAKER CALLS OUT LA COUNTY’S ‘USELESS’ MANAGEMENT OVER WILDFIRE THAT DESTROYED PEOPLE’S LIVES

“That’s what they do. Soon as the problem comes up, then they try to do what they can do to fix it. Instead of being on the offensive a year before the fires,” Jenner further explained her analogy.

Jenner criticized Gov. Gavin Newsom’s response to the wildfires, highlighting how she has had properties affected by several fires over the years and that they happen “all the time.”

“This is devastating stuff. And they’re not on the offense,” said Jenner, acknowledging the massive winds that contributed to the level of devastation from the flames.

Malibu, CA – January 08: Beachfront homes are devastated by the Palisades fire on PCH on Wednesday, Jan. 8, 2025 in Malibu, CA. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Outside of the unusually windy conditions, California has been dealing with a water infrastructure problem, which Jenner highlighted.

“Certainly in the 60s, we had the California aqueduct come through. The greatest project in history [for] water in California. Since then, we’ve been run by liberal Democrats and we just get less and less. And it’s just, it’s a shame because there are a lot of things you can do, and they just have their priorities in the wrong spot,” she said.

California suffers from an outdated water reserves system that was incapable of storing all the water from the record rainfall last year. Without the reservoirs providing adequate storage, much of the rain water had to be dumped into the ocean.

Jenner detailed how she believes that California has and will continue to swing more Republican after the wildfire mismanagement in L.A. and President-elect Donald Trump’s election victory.

“What [Trump] did to this state, if you looked at over the last few elections, the amount of blue which was on our state, it was half the state. Now it’s about a third,” said Jenner, detailing how most of the California blue zones are in the major metropolitan areas of San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego.

“I hope the people of California can really change their thinking. And I think what’s happening [with] this fire is going to change their thinking. It’s things like this that have to happen,” said Jenner, explaining how California as a whole is controlled by Democrats.

“They control the money. They control the votes. They control the unions. And to me, the whole state is like a big scam,” she said.

Read the full article from Here

Alaska

Alaska Sports Scoreboard: Feb. 28, 2026

High school

Basketball

Girls

Monday

Kenai Central 63, Nikiski 33

Colony 68, Grace Christian 46

Tuesday

South 33, East 22

Service 62, Dimond 47

Redington 47, Houston 17

Wasilla 60, Mountain City Christian Academy 44

Kenai Central 54, Homer 27

Bartlett 53, Chugiak 29

Mt. Edgecumbe 59, Sitka 50

Wednesday

Shishmaref 82, Aniguiin 34

Shaktoolik 73, Anthony Andrews 25

Savoonga 61, White Mountain 56

Glennallen 68, Nenana 26

Seward 72, Houston 8

Service 65, South 26

Brevig Mission 65, Koyuk Malimiut 47

Chief Ivan Blunka 67, Manokotak 30

Thursday

White Mountain 76, Anthony Andrews 50

Hoonah 44, Skagway 21

Koyuk Malimiut 53, Aniguiin 51

Nunamiut 74, Kali 17

Glennallen 25, Delta 20

Birchwood Christian 42, Nanwalek 24

Ninilchik 33, Lumen Christi 30

Dimond 59, Chugiak 54

Shaktoolik 57, Savoonga 24

Colony 43, Mountain City Christian 41

Alak 67, Meade River 66

Lathrop 42, West Valley 34

Seward 78, Nikiski 32

Grace Christian 56, Soldotna 41

Kenai Central 56, Houston 10

Wasilla 72, Palmer 27

Bristol Bay 55, Chief Ivan Blunka 30

Nome-Beltz 33, Bethel 24

Scammon Bay 46, Ignatius Beans 28

Aniak 83, Akiachak 45

Shishmaref 53, Brevig Mission 51

Metlakatla 64, Haines 21

Friday

Chief Ivan Blunka 68, Togiak 38

Meade River 80, Nuiqsut Trapper 34

Nunamiut 68, Alak 50

Cook Inlet Academy 33, Birchwood Christian 32

Meade River 71, Kali 46

Kalskag 62, Akiachak 47

Hoonah 39, Kake 37

Soldotna 36, Palmer 23

Delta 54, Valdez 45

Unalakleet 61, Chevak 45

Minto 46, Hutchison 26

West 71, Bartlett 65

Seward 63, Homer 19

North Pole 61, West Valley 25

Newhalen 78, Chief Ivan Blunka 40

Birchwood Christian 43, Nanwalek 28

Bethel 42, Nome-Beltz 35

Aniak 65, Tuluksak 50

Scammon Bay 49, St. Mary’s 38

Monroe Catholic 84, Galena 42

Ketchikan 57, Redington 24

Meade River 69, Alak 62

Fort Yukon 60, Jimmy Huntington 19

Grace Christian 50, Kenai Central 45

Shaktoolik 44, Shishmaref 34

Wrangell 44, Petersburg 31

Saturday

Unalakleet 41, Chevak 37

Meade River 54, Nunamiut 51

Monroe Catholic 68, Galena 32

Newhalen 32, Bristol Bay 26

Cook Inlet Academy 65, Birchwood Christian 32

Soldotna 55, Palmer 42

Nunamiut 48, Meade River 46

Boys

Sunday

SISD 51, Yakutat 18

Monday

Eagle River 54, Birchwood Christian 52

Colony 69, Grace Christian 64

Kenai Central 68, Nikiski 30

Tuesday

Susitna Valley 48, Lumen Christi 46

Dimond 54, Service 47

South 50, East 46

Houston 53, Redington 40

Wasilla 63, Mountain City Christian Academy 50

Kenai Central 74, Homer 47

Chugiak 66, Bartlett 45

Wednesday

SISD 59, Yakutat 17

Shishmaref 85, Savoonga 45

Hydaburg 58, Hoonah 51

Shaktoolik 103, Martin L Olson 49

Skagway 68, Gustavus 24

Davis-Romoth 108, Kobuk 31

Klawock 68, SISD 27

Glennallen 61, Nenana 57

Gambell 46, James C Isabell 31

South 63, Service 60

Seward 81, Houston 73

Bristol Bay 80, Chief Ivan Blunka 61

Mt. Edgecumbe 68, Sitka 59

Scammon Bay 79, Ignatius Beans 34

Brevig Mission 73, Aniguiin 67

Thursday

Savoonga 69, James C Isabell 61

Hoonah 64, Yakutat 45

Alak 88, Meade River 38

Shaktoolik 110, Brevig Mission 30

Chief Ivan Blunka 62, Tanalian 39

Nunamiut 66, Kali 48

Davis-Romoth 91, Buckland 45

Ninilchik 83, Lumen Christi 38

Monroe Catholic 43, North Pole 42

King Cove 57, Bristol Bay 41

Metlakatla 52, Haines 46

Nome-Beltz 62, Bethel 45

Skagway 79, Angoon 30

Birchwood Christian 69, Nanwalek 63

Dimond 60, Chugiak 57

Colony 75, Mountain City Christian Academy 49

Wasilla 66, Palmer 40

Klawock 63, Hydaburg 49

Shishmaref 58, Gambell 47

Grace Christian 63, Soldotna 52

Seward 66, Nikiski 51

Kenai Central 61, Houston 48

Nuiqsut Trapper 64, Alak 51

West Valley 51, Lathrop 44

Akiachak 83, Akiak 64

Scammon Bay 62, Marshall 54

Friday

Hoonah 71, SISD 38

Hydaburg 61, Kake 50

Chief Ivan Blunka 73, Bristol Bay 68

Kali 63, Meade River 45

Nunamiut 80, Nuiqsut Trapper 62

Service 58, East 50

Angoon 61, Hoonah 56

Cook Inlet Academy 73, Birchwood Christian 34

King Cove 75, Newhalen 39

Petersburg 53, Wrangell 20

Skagway 46, Klawock 43

Metlakatla 50, Haines 42

Nome-Beltz 71, Bethel 43

Juneau-Douglas 67, Tri-Valley 45

Wasilla 73, Chugiak 43

West 83, Bartlett 36

Colony 73, Kodiak 32

Delta 62, Valdez 54

West Valley 72, North Pole 46

Palmer 57, Soldotna 47

Nenana 55, Cordova 53

Chief Ivan Blunka 63, Manokotak 48

Scammon Bay 67, St. Mary’s 54

Unalakleet 87, Chevak 64

Shaktoolik 73, Shishmaref 54

Saturday

Unalakleet 95, Chevak 44

Cook Inlet Academy 95, Birchwood Christian 50

South 73, Eagle River 35

Palmer 45, Soldotna 40

• • •

College

Hockey

Friday

UAF 2, UAA 0

Saturday

UAA vs. UAF (Late)

• • •

Women’s basketball

Thursday

UAA 79, Western Oregon 58

Saint Martin’s 99, UAF 59

Saturday

Western Oregon 73, UAF 58

UAA vs. Saint Martin’s (Late)

• • •

Men’s basketball

Thursday

Saint Martin’s 77, UAF 65

UAA 80, Western Oregon 59

Saturday

UAF 82, Western Oregon 74

UAA vs. Saint Martin’s (Late)

• • •

NAHL

Friday

Anchorage Wolverines 5, Chippewa Steel 4

Saturday

Anchorage Wolverines vs. Chippewa Steel (Late)

• • •

2026 Fur Rondy Frostbite Footrace

5K Women

1. Courtney Spann, Anchorage, AK 26:05; 2. Racheal Kerr, Alakanuk, AK 26:07; 3. Anne-Marie Meyer, Yakima, WA 27:06; 4. Riann Anderson, Anchorage, AK 27:09; 5. Nevaeh Dunlap, Anchorage, AK 27:47; 6. Rita McKenzie, Anchorage, AK 27:55; 7. Marta Burke, Anchorage, AK 28:08; 8. Rachel Penney, Eagle River, AK 29:24; 9. Victoria Grant, Eagle River, AK 29:33; 10. Gretchen Klein, Craig, AK 29:36; 11. Penny Wasem, Willow, AK 29:42; 12. Chantel Van Tress, JBER, AK 29:51; 13. Janet Johnston, Anchorage, AK 30:18; 14. Dianna Clemetson, Anchorage, AK 31:33; 15. Sarah Hoepfner, Anchorage, AK 32:02; 16. Ireland Hicks, Seward, AK 33:21; 17. Lilly Schoonover, Seward, AK 33:21; 18. Suzanne Smerjac, Anchorage, AK 33:32; 19. Mindy Perdue, Wasilla, AK 34:12; 20. Oxana Bystrova, Anchorage, AK 34:23; 21. Charlene Canino, Anchorage, AK 34:49; 22. Tami Todd, Wasilla, AK 34:50; 23. Kaiena Tuiloma, Anchorage, AK 34:57; 24. Meg Kurtagh, Anchorage, AK 35:05; 25. Larue Groves, Chugiak, AK 35:13; 26. Rose Van Hemert, Anchorage, AK 36:12; 27. Morgan Daniels, Crestview, FL 36:25; 28. Elle Kauppi, Anchorage, AK 37:31; 29. Miranda Gibson, Wasilla, AK 37:46; 30. Caroline Secoy, JBER, AK 37:46; 31. Jordyn McNeil, Palmer, AK 38:29; 32. Ryan Plant, Palmer, AK 38:30; 33. Samantha Williams, Anchorage, AK 39:00; 34. Wendy Heck, Willow, AK 39:33; 35. Stephanie Kesler, Anchorage, AK 43:29; 36. Denise Wright, Anchorage, AK 43:50; 37. Brie Flores, Anchorage, AK 46:14; 38. Anabell Lewis, Anchorage, AK 46:15; 39. Jessica Lose, Anchorage, AK 46:18; 40. Kaylie Bylsma, Anchorage, AK 46:18; 41. Alicyn Giannakos, Anchorage, AK 46:38; 42. Natasha Henderson, Anchorage, AK 46:39; 43. Shannon Thompson, Anchorage, AK 48:40; 44. Heather Holcomb, Palmer, AK 48:40; 45. Debora Milligan, Iron Mountain, MI 57:36; 46. Rondy McKee, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico, 57:37

5K Men

1. James Miller, Anchorage, AK 18:28; 2. Barefoot Bogey, Woburn, MA 18:37; 3. Keaden Dunlap, Anchorage, AK 19:22; 4. Maximus Tagle-Martinez, JBER, AK 20:03; 5. Gavin Hanks, Eagle River, AK 20:59; 6. Patrick McAnally, Anchorage, AK 21:37; 7. Anthony Gomez, Anchorage, AK 22:37; 8. Christopher Hilliard, JBER, AK 23:20; 9. Terry Schimon, University Place, WA 23:37; 10. Ryan Moldenhauer, Anchorage, AK 24:12; 11. Matthew Haney, Anchorage, AK 24:24; 12. Dan Burke, Anchorage, AK 25:44; 13. Paul Chandanabhumma, Seattle, WA 25:52; 14. Woods Miller, Wasilla, AK 26:51; 15. Bill Grether, Anchorage, AK 27:10; 16. Charles Simmons, Anchorage, AK 27:15; 17. Jacob Cassianni, Anchorage, AK 27:32; 18. John Brewer, Anchorage, AK 28:09; 19. Dustin Whitcomb, Eagle River, AK 28:14; 20. Greg MacDonald, Anchorage, AK 28:28; 21. Kevin Redmond, Anchorage, AK 28:38; 22. Olin Jensen, Anchorage, AK 28:45; 23. Michael Loughlin, Anchorage, AK 29:18; 24. Daryl Schaffer, Anchorage, AK 30:30; 25. Aaron Paul, Anchorage, AK 30:37; 26. Mark Ireland, Anchorage, AK 30:37; 27. Christopher Pineda, Eagle River, AK 30:39; 28. Eric Jostsons, Anchorage, AK 31:07; 29. Justin Fitzgerald, Anchorage, AK 31:36; 30. Steve Lambert, Anchorage, AK 32:09; 31. Justin Atteberry, Anchorage, AK 32:21; 32. Matthew Beardsley, Anchorage, AK 34:07; 33. Caleb Penney, Eagle River, AK 34:21; 34. Evgenii Ivanov, Anchorage, AK 34:22; 35. Eliezer Rivera, Anchorage, AK 35:12; 36. David Massey, Anchorage, AK 35:38; 37. Zachary Todd, Wasilla, AK 35:39; 38. Ed Hills, Anchorage, AK 36:52; 39. Chucky Williams, Anchorage, AK 36:54; 40. Rick Taylor, Wasilla, AK 39:32; 41. Steven Shamburek, Anchorage, AK 43:48; 42. Dave Jones, Anchorage, AK 46:46; 43. Tom Meacham, Anchorage, AK 46:47; 44. Russell Martin, Ventura, CA 47:34; 45. David Martin, Ventura, CA 47:45; 46. Zachary Lounsberry, Palmer, AK 48:41

2.5K Women

1. Kelsey Kramer, Wilmington, NC 13:50; 2. Alannah Dunlap, Anchorage, AK 15:09; 3. Kelsea Johnson, Anchorage, AK 15:45; 4. Kirsten Kling, Anchorage, AK 16:05; 5. Miriam Hayes, Anchorage, AK 16:55; 6. Brianna Slayback, Anchorage, AK 17:04; 7. Haley Hoffman, Alexandria, VA 18:01; 8. Kathryn Hoke, Anchorage, AK 18:32; 9. Rachel Stein, Palmer, AK 18:51; 10. Shayla Harrison, Anchorage, AK 19:29; 11. Danielle Harrison, Anchorage, AK 19:30; 12. Nikki Withers, Tacoma, WA 19:32; 13. Michele Robuck, Anchorage, AK 20:20; 14. Jess Adams, Anchorage, AK 20:20; 15. Ashley Martinez, Miami, FL 20:24; 16. Laura Casanover, Houston, TX 20:31; 17. Adylaine Hacker, Eagle River, AK 21:59; 18. Mary Stutzman, Tallahassee, FL 22:59; 19. Jean Bielawski, Anchorage, AK 23:24; 20. Cheryl Parmelee, Mount Dora, FL 25:45; 21. Ruth Anderson, Anchorage, AK 26:56; 22. Morgan Withers, Tacoma, WA 27:17; 23. Terri Agee, Anchorage, AK 27:31; 24. Chyll Perry, Anchorage, AK 27:35; 25. Denice Withers, Yakima, WA 28:09; 26. Sarah Camacho, Anchorage, AK 28:20; 27. Katheryn Camacho, Anchorage, AK 28:21; 28. Brooke Whitcomb, Eagle River, AK 28:41; 29. Kristine Withers, Tacoma, WA 31:19; 30. Penny Helgeson, Anchorage, AK 33:56; 31. Kimberly Halstead, Eagle River, AK 34:02; 32. Julianna Halstead, Eagle River, AK 34:09

2.5K Men

1. Riley Howard, Anchorage, AK 10:54; 2. Julian Salao, Anchorage, AK 12:26; 3. Mitch Paisker, Anchorage, AK 16:05; 4. Kaden Bartholomew, Anchorage, AK 16:24; 5. Brandon Bartholomew, Anchorage, AK 16:25; 6. Michael Hayes, Anchorage, AK 16:30; 7. Calvin Stein, Anchorage, AK 18:51; 8. Jesse Ackerson, Anchorage, AK 19:42; 9. Clinton Hacker, Eagle River, AK 21:59; 10. Daniel Hjortstorp, Gakona, AK 22:20; 11. Atlas Hjortstorp, Gakona, AK 22:20; 12. Craig Withers, Tacoma, WA 27:18; 13. Jordan Ralph, Tacoma, WA 27:19; 14. Scott King, Anchorage, AK 28:20; 15. Shawn Withers, Yakima, WA 31:18; 16. John Ruthe, Anchorage, AK 35:53

Arizona

Arizona Lottery Powerball, The Pick results for Feb. 28, 2026

Odds of winning the Powerball and Mega Millions are NOT in your favor

Odds of hitting the jackpot in Mega Millions or Powerball are around 1-in-292 million. Here are things that you’re more likely to land than big bucks.

The Arizona Lottery offers multiple draw games for those aiming to win big.

Here’s a look at Saturday, Feb. 28, 2026 results for each game:

Winning Powerball numbers

06-20-35-54-65, Powerball: 10, Power Play: 4

Check Powerball payouts and previous drawings here.

Winning The Pick numbers

09-12-15-25-31-35

Check The Pick payouts and previous drawings here.

Winning Pick 3 numbers

6-1-8

Check Pick 3 payouts and previous drawings here.

Winning Fantasy 5 numbers

07-10-22-30-36

Check Fantasy 5 payouts and previous drawings here.

Winning Triple Twist numbers

08-09-14-17-30-41

Check Triple Twist payouts and previous drawings here.

Feeling lucky? Explore the latest lottery news and results

What time is the Powerball drawing?

Powerball drawings are at 7:59 p.m. Arizona time on Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays.

How much is a Powerball lottery ticket today?

In Arizona, Powerball tickets cost $2 per game, according to the Arizona Lottery.

How to play the Powerball

To play, select five numbers from 1 to 69 for the white balls, then select one number from 1 to 26 for the red Powerball.

You can choose your lucky numbers on a play slip or let the lottery terminal randomly pick your numbers.

To win, match one of the 9 Ways to Win:

- 5 white balls + 1 red Powerball = Grand prize.

- 5 white balls = $1 million.

- 4 white balls + 1 red Powerball = $50,000.

- 4 white balls = $100.

- 3 white balls + 1 red Powerball = $100.

- 3 white balls = $7.

- 2 white balls + 1 red Powerball = $7.

- 1 white ball + 1 red Powerball = $4.

- 1 red Powerball = $4.

There’s a chance to have your winnings increased two, three, four, five and 10 times through the Power Play for an additional $1 per play. Players can multiply non-jackpot wins up to 10 times when the jackpot is $150 million or less.

Are you a winner? Here’s how to claim your lottery prize

All Arizona Lottery retailers will redeem prizes up to $100 and may redeem winnings up to $599. For prizes over $599, winners can submit winning tickets through the mail or in person at Arizona Lottery offices. By mail, send a winner claim form, winning lottery ticket and a copy of a government-issued ID to P.O. Box 2913, Phoenix, AZ 85062.

To submit in person, sign the back of your ticket, fill out a winner claim form and deliver the form, along with the ticket and government-issued ID to any of these locations:

Phoenix Arizona Lottery Office: 4740 E. University Drive, Phoenix, AZ 85034, 480-921-4400. Hours: 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, closed holidays. This office can cash prizes of any amount.

Tucson Arizona Lottery Office: 2955 E. Grant Road, Tucson, AZ 85716, 520-628-5107. Hours: 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, closed holidays. This office can cash prizes of any amount.

Phoenix Sky Harbor Lottery Office: Terminal 4 Baggage Claim, 3400 E. Sky Harbor Blvd., Phoenix, AZ 85034, 480-921-4424. Hours: 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Sunday, closed holidays. This office can cash prizes up to $49,999.

Kingman Arizona Lottery Office: Inside Walmart, 3396 Stockton Hill Road, Kingman, AZ 86409, 928-753-8808. Hours: 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday, closed holidays. This office can cash prizes up to $49,999.

Check previous winning numbers and payouts at https://www.arizonalottery.com/.

This results page was generated automatically using information from TinBu and a template written and reviewed by an Arizona Republic editor. You can send feedback using this form.

California

San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan officially announce run for California governor

Watch CBS News

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO4 days ago

Denver, CO4 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT