North Carolina

A local reporter’s experience covering Western North Carolina in the wake of Helene

See Helene’s aftermath over Swannanoa in North Carolina

Drone video from Oct. 3 shows Helene’s floodwaters receding and crews beginning the cleanup process after the storm brought devastation to Swannanoa and surrounding parts in North Carolina

Reuters

It’s hard to put into words what it’s like to pull up to where a family’s home once stood and see mounds and mounds of cracked, beige dirt.

To notice that a wooden, split-rail fence managed to withstand more than 20 feet of swift-moving floodwaters, yet not realize until later that the fence bordered the home’s driveway. To walk next door to a tiling warehouse, where men in white coveralls and muddy black boots are removing storm debris, and ask if there was a house next to their place of business.

And, when one answers in the affirmative, to have him walk you and your photographer to the spot where a family once laughed and cried and prayed together – all while knowing the tragic outcome of their story.

My job is to put these kinds of experiences into words. More than a week later, I’m still struggling to.

I tried to begin this piece – a brief description of my reporting in Asheville, North Carolina, as part of the USA TODAY Network’s Hurricane Helene coverage – in a light-hearted way.

I thought about starting with how we in the Asheville Citizen-Times newsroom had to use gallon buckets to force-flush the toilets because there was no running water. About how bags of cat litter sat in the halls in case reporters needed to take them home to create a makeshift bathroom.

I thought about describing the lovely man I encountered as I traipsed around a homeless encampment, who was all too willing to show me where a tree fell on his tent and legs when Helene swept through Western North Carolina. His rebuilt camp is the tidiest I’ve ever seen – and my beat has taken me through quite a few.

But today, on an unseasonably warm Tuesday in late October, I wrote and rewrote the beginning of this piece. Because this afternoon – and the afternoon before it – my heart is heavy.

It’s heavy for the Dryes and Wiselys, two families who lost almost everyone to the floods, and the other Asheville survivors I spoke to. For the families who are still waiting to hear about loved ones.

For the homeless residents who told me they fear some of their acquaintances who perished in the storm will never be claimed by family because of their transient status. And for the Western North Carolina community as a whole, which is mourning the loss of homes and pets and landmarks and an art colony that disappeared entirely in mere hours.

As students, journalism hopefuls are taught to keep an arm’s length from stories and sources. Reporters must remain objective, professors stress, which means maintaining a certain level of detachment. If you care too much, your feelings might find their way into a piece and influence your ability to tell the story fairly.

But what this (well-intentioned) lesson leaves out is humanity.

How can one travel to natural disaster-ravaged areas, interview families who lost parents and siblings and children and grandparents, and not be impacted?

How can a reporter spend hours at a barricade situation involving an 11-month-old girl and not feel emotional when they’re told a chaplain has been called to the hospital where the baby was rushed following a gunshot wound to her head?

And how can journalists be expected to cover school shootings – as the Texas-based photographer I worked alongside in Asheville did in Uvalde in 2022 – and remain emotionless?

I don’t believe reporters can. And I also believe this is something those in the field have long known.

At the first newspaper I worked at, I had an editor who was decades into his career. He knew I was fresh out of college and hadn’t chosen the breaking news/public safety beat (which I’m so thankful I was assigned to because it’s now my specialty.) He knew that I’d write a lot of hard stories in my career.

So, one day, he offered me a piece of advice: The moment this stuff – the really tragic, heavy stories, he meant – stops getting to you, get out of the profession. Or, at the very least, take a long enough break to where you can feel the humanity of this again.

Eight or so years later, I remember those words like he spoke them yesterday. So, on days when my heart is heavy, I think it’s OK to feel this way.

Because what’s happening in Western North Carolina is heavy – and it will be for that community and those journalists for a while.

Isabel is an investigative reporter covering breaking news and public safety, with an eye toward some of Delaware’s most vulnerable: children, those struggling with addiction, and those with mental illness. She can be reached at ihughes@delawareonline.com or via X at @izzihughes_

North Carolina

Life-threatening injuries reported after shooting on I-73 South near Wendover Avenue, Greensboro police say

GREENSBORO, N.C. (WGHP) — One person was left with life-threatening injuries in an overnight shooting Sunday, according to the Greensboro Police Department.

At 12:52 a.m., officers responded to a man down call at Interstate 73 South just before the Wendover Avenue exit and found one shooting victim with life-threatening injuries. They were taken to a local hospital.

I-73 South at Wendover Avenue was closed following the shooting. As of 10:22 a.m. Sunday, the road is still closed.

No suspect information was available.

The investigation is ongoing.

North Carolina

Seth Trimble returns to lead No. 12 North Carolina past Ohio State 71-70

ATLANTA (AP) — Henri Veesaar scored the winning basket on a dunk with 7.2 seconds remaining off a pass from a stumbling Seth Trimble, and No. 12 North Carolina held off Ohio State 71-70 on Saturday.

Trimble, playing his first game since breaking his left forearm in a Nov. 9 training mishap, wanted to shoot but tripped as he spun into the lane. As the senior guard was falling, he dished the ball to Veesaar, who slipped past his defender for the emphatic slam.

Ohio State had two chances to pull off the upset.

John Mobley Jr. missed a 3-point try, only to have Devin Royal grab the offensive rebound under the basket. He went back up ahead of the horn, but Caleb Wilson blocked the shot to preserve the win for the Tar Heels.

Trimble, who played with a wrap covering much of his left arm, and Veesaar both finished with 17 points. Wilson led North Carolina (11-1) with 20.

Trimble also did a stellar defensive job on Ohio State star Bruce Thornton, who was held to 16 points on 7-of-16 shooting. He came into the game hitting 60.2% from the field.

Royal led the Buckeyes (8-3) with 18 points.

Mobley put Ohio State ahead on a 3-pointer with 48.7 seconds to go, also drawing a foul that made it a four-point play for a 70-67 lead.

Trimble hit a drive in the lane to cut the margin, and Jarin Stevenson made a steal as Ohio State tried to get the ball into the frontcourt to set up the winning basket.

It was the second game of the CBS Sports Classic at State Farm Arena in Atlanta. Kentucky defeated No. 22 St. John’s 78-66 in the opener.

Up next

Ohio State hosts Grambling State on Tuesday.

North Carolina is back in Chapel Hill to face East Carolina on Monday.

___

Get poll alerts and updates on the AP Top 25 throughout the season. Sign up here and here (AP mobile app). AP college basketball: https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-basketball-poll and https://apnews.com/hub/college-basketball

North Carolina

It’s official, North Carolina professors will have to publicly post syllabi

The UNC System has officially adopted a policy to force all state university professors to publicly post their syllabi.

System President Peter Hans approved the policy measure Friday evening, which didn’t require a vote from the UNC Board of Governors. The new regulation was posted on the System’s website without a public announcement and while all campuses are on winter break.

The decision puts North Carolina in league with other Southern states like Florida, Georgia, and Texas; two of which legislatively mandate syllabi to be public records.

The UNC System’s new syllabi policy not only requires the documents to be public records, but universities must also create a “readily searchable online platform” to display them.

All syllabi must include learning outcomes, a grading scale, and all course materials students are required to buy. Professors must also include a statement saying their courses engage in “diverse scholarly perspectives” and that accompanying readings are not endorsements. They are, however, allowed to leave out when a class is scheduled and what building it will be held in.

This policy goes into effect on Jan. 15, but universities aren’t required to publicly post syllabi or offer the online platform until fall 2026.

Hans had already announced his decision to make syllabi public records a week in advance through an op-ed in the News & Observer. He said the move would provide greater transparency for students and the general public, as well as clear up any confusion among the 16-university System.

Before now, a spokesperson told WUNC that the syllabus regulations were a “campus level issue” that fell outside of its open records policy. That campus autonomy assessment began to shift after conservative groups started making syllabi requests – and universities reached opposing decisions on how to fulfill them.

Lynn Hey (left); Liz Schlemmer (right)

Earlier this year, UNC-Chapel Hill sided with faculty, deciding that course materials belong to them and are protected by intellectual property rights. UNC Greensboro, however, made faculty turn in all of their syllabi to fulfill any records requests.

“Having a consistent rule on syllabi transparency, instead of 16 campuses coming up with different rules, helps ensure that everyone is on the same page and similarly committed heading into each new semester,” Hans said in the op-ed.

Still, faculty members from across the UNC System tried to convince Hans to change his mind before his decision was finalized.

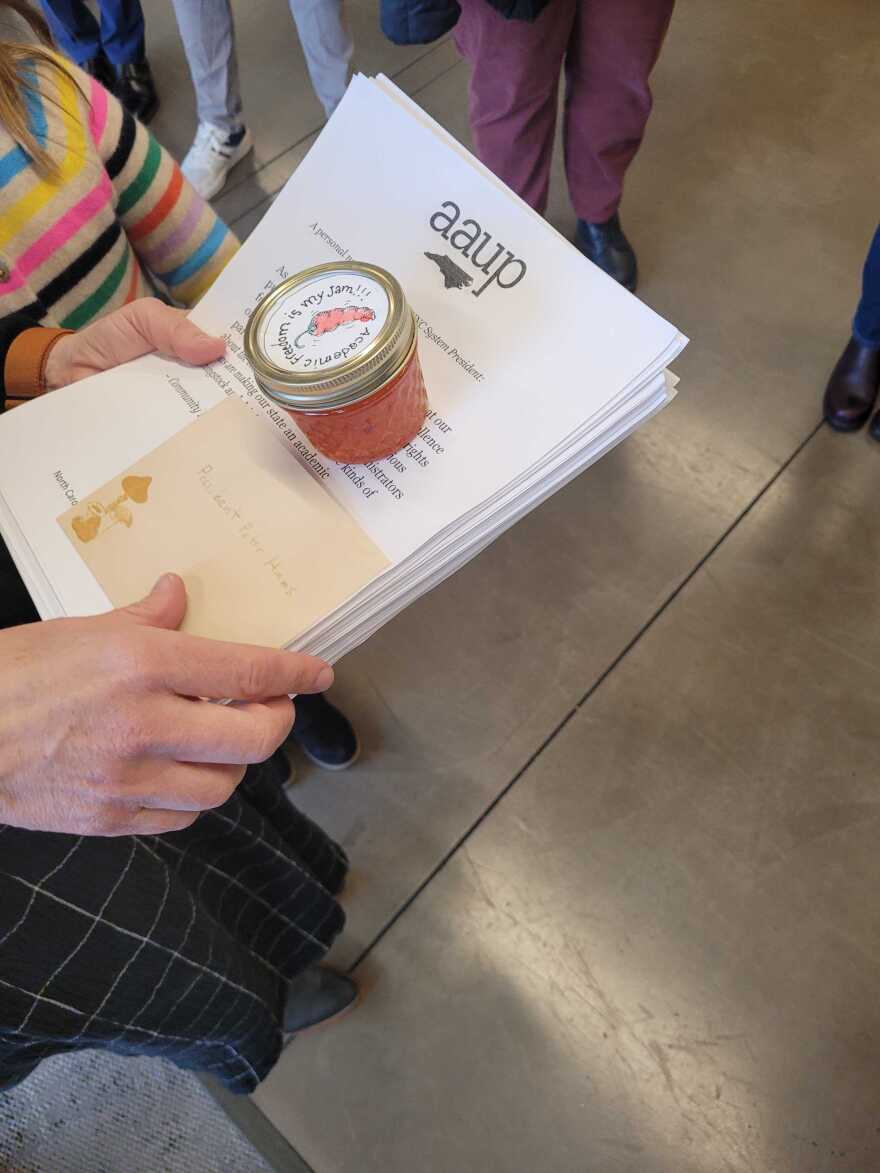

About a dozen attempted to deliver a petition to his office days after the op-ed. More than 2,800 faculty, staff, students, and other campus community members signed the document – demanding Hans protect academic freedom.

One of those signatories is Michael Palm, the president of UNC-Chapel Hill’s AAUP Chapter. He spoke to WUNC shortly before the petition drop-off.

“Transparency, accountability accessibility – these are important aspects of a public university system, but that’s not what this is about,” Palm said. “This is about capitulating to pressure at the state level and at the federal level to scrutinize faculty and intimidate faculty who are teaching unpopular subjects right now.”

A public records request from The Oversight Project put UNC-Chapel Hill at the epicenter of the syllabi public records debate in North Carolina this summer.

The organization, which is a spin-off of the conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation, requested course materials from 74 UNC-Chapel Hill classes. This included syllabi, lecture slides, and presentation materials that contained words like diversity, equity, and inclusion; LGBTQ+; and systems of oppression.

Mike Howell, The Oversight Project’s president, told WUNC in September that his goal is to ultimately get DEI teachings or what he calls “garbage out of colleges and universities.”

“One of the ends will be the public can scrutinize whether their taxpayer dollars are going toward promulgating hard-left, Marxists, racist teachings at public universities,” Howell said. “I think there’s a lot of people in North Carolina and across the country that would take issue to that.”

Faculty say pressure from outside forces is why they petitioned Hans to protect their rights to choose how and when to disseminate syllabi.

“There are people who do not have good intentions or do not have productive or scholarly or educational desires when looking at syllabi,” said Ajamu Dillahunt-Holloway, a history professor at NC State. “They’re more interested in attacking faculty and more so attacking ideas that maybe they have not fully engaged with themselves.”

In his op-ed, Hans said the UNC System will do everything it can to “safeguard faculty and staff who may be subject to threats or intimidation simply for doing their jobs.”

Hans has yet to share details about what those measures will look like, and turned down a request from WUNC for an interview to explain what safety measures the UNC System may enact.

WUNC partners with Open Campus and NC Local on higher education coverage.

-

Iowa7 days ago

Iowa7 days agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoHow much snow did Iowa get? See Iowa’s latest snowfall totals

-

Maine5 days ago

Maine5 days agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Maryland7 days ago

Maryland7 days agoFrigid temperatures to start the week in Maryland

-

South Dakota1 week ago

South Dakota1 week agoNature: Snow in South Dakota

-

New Mexico5 days ago

New Mexico5 days agoFamily clarifies why they believe missing New Mexico man is dead

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago‘Love being a pedo’: Metro Detroit doctor, attorney, therapist accused in web of child porn chats

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoOpinion | America’s Military Needs a Culture Shift