Mississippi

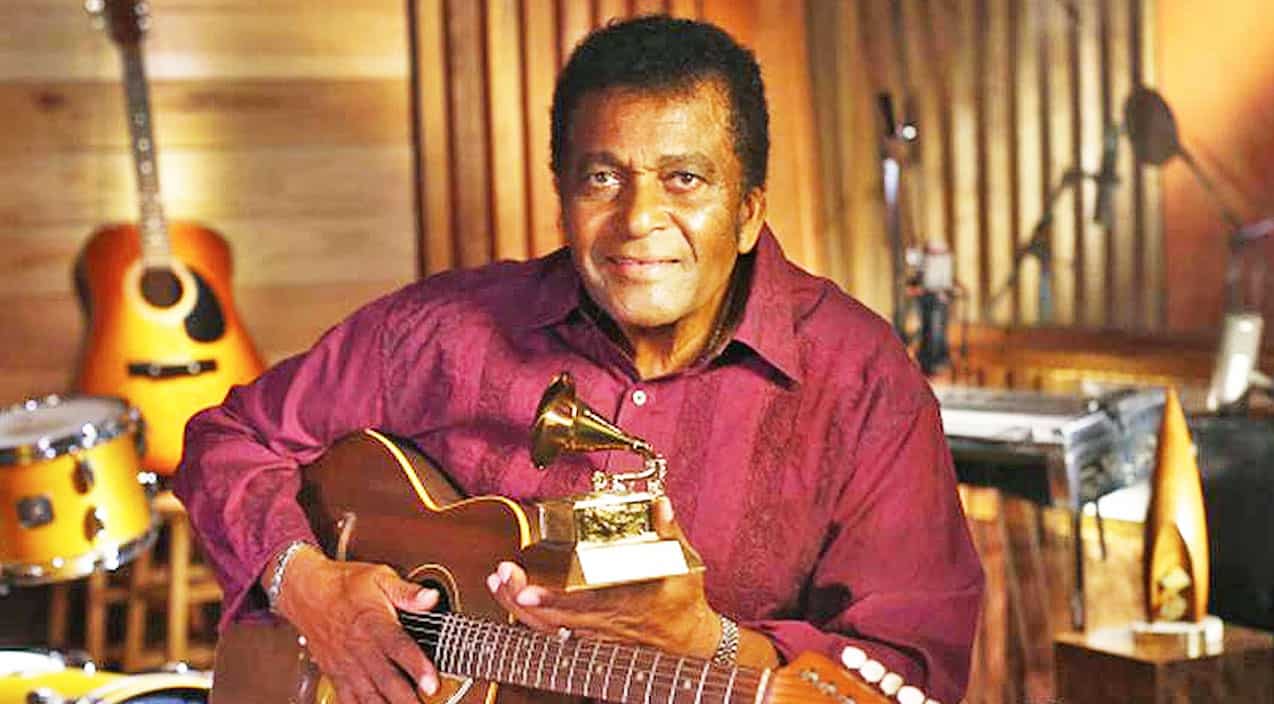

The Man from Sledge: Mississippi legend Charley Pride

From baseball to country music, Mississippi-native Charley Pride, a man of humble beginnings, left a big mark on the world.

I stare at the blank document on my computer, waiting for the words to flow. While I wait, Charley Pride is singing in the background—I need some inspiration. Kiss an Angel Good Morning is the current song, and I find myself singing along with this familiar piece instead of typing. YouTube videos provide many of his number-one hits. They document his performances at county fairs, on The Marty Stuart Show, a duet with Johnny Cash, live concerts, and more.

When was the first time you heard Charley Pride sing? Was it from a record or in person? Did you find yourself being drawn in to listen to his rich, baritone voice?

What came from my throat was my voice, no one else’s. No one had ever told me that whites were supposed to sing one kind of music and blacks another—I sang what I liked in the voice I had.

Excerpt from Pride: The Charley Pride Story

Mississippi Origins

Charley, the fourth of eleven children, was born on March 18, 1934, to Fowler MacArthur Pride and Tessie B. Stewart Pride. His father named him Charl, but his name became Charley Frank Pride when the midwife completed the birth certificate and the name remained with him throughout his life.

His parents were sharecroppers and cotton pickers. Their portion of land was located approximately 50 miles south of Memphis, in the northwest corner of Mississippi, near Sledge. The love for country music originated with Fowler Pride. When Charley was young, his father purchased a Philco radio for the family. They enjoyed listening to the WSM-AM broadcasts from the Grand Ole Opry. He grew to love country music along with Gospel and the blues.

Charley purchased his first guitar for ten dollars, a Silvertone, from the Sears Roebuck catalog at age fourteen. Guitar lessons came from listening to the music he heard on the radio and practicing. His teachers were his radio heroes: Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, and Hank Williams. But music wasn’t Charley’s only talent.

Barriers and Bridges in Baseball

Two years later, Charley left his family to play baseball in the Iowa State League and then professionally with the Negro American League as a pitcher. In 1953, Charley signed a contract with the Boise Yankees, a Class C farm team associated with the New York Yankees. A shoulder injury hampered his pitching ability.

Pride moved around with several teams: the El Paso Kings and the Yaquis in Nogales, Mexico, before rejoining the Memphis Red Sox in 1956. He won 14 games as a pitcher, which brought him into a position with the Negro American League All-Star Team. While playing on the team, he had the opportunity to play against a group of major-league players called the Willie Mays All-Stars, facing off in the field against Hank Aaron and Willie Mays. Eventually, after playing in several exhibition games, Charley brought home a significant victory for the Negro League all-stars. In four innings, Charley delivered a shutout ballgame, a major upset.

Towards the end of 1956, Pride was drafted by the U.S. Army. He had basic training at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, then assigned to Fort Carson, Colorado. And he continued to play baseball in the “All Army” sports. The team in 1957 consisted of men who would play professionally, Willie Kirkland, George Altman, and Eddie Kopacz. Pride also continued singing.

There were times when he was asked to sing at the officer’s club, an unusual request for a black man at that point in time.

His baseball idol, Jackie Robinson, broke the color barrier in baseball in 1947 when he played in the Major Leagues. The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum website quotes Pride: “To say that he was my idol would be an understatement. As far as I was concerned, Jackie Robinson had rewritten the future.”

As a player and then as a singer, Charley often sang the National Anthem for baseball games. In 2010, he became part-owner of the Texas Rangers. He enjoyed being a participant at their training camps in Port Charlotte and Pompano Beach, Florida, and Surprise, Arizona, working out with the team and hosting an annual concert at the clubhouse for the staff and players. After his death the team’s training complex in Surprise, Arizona was renamed “Charley Pride Field.”

Montana to Nashville

Charley met Rozene Cohran when he was playing baseball in Memphis. They married in 1956 and later had three children: Kraig, Dion, and Angela. He received his discharge from the Army in 1958, and it was back to the Memphis Red Sox. Pride had a passion for playing baseball. And he continued to find ways to play until he turned to a full-time music career.

Charley and Rozene made the transition in 1960 to Helena, Montana where he worked for the Anaconda Mining Company. Charley continued playing baseball for the East Helena Smelterites, a semi-pro baseball team.

An invitation came to try out for the Los Angeles Angels in 1961. The tryouts didn’t go well – after two weeks, he returned to Montana to continue work at the smelter. Charley took advantage of opportunities to play his guitar and sing at churches, nightclubs, honky-tonks, and perform the national anthem at the baseball games.

A local disc jockey, Tiny Stokes, introduced Charley to country music singers Red Sovine and Red Foley. For one of their shows, they asked him to sing Lovesick Blues and Heartaches by the Number. The foundation was being laid for Charley Pride’s music career.

Another opportunity for an audition in Florida with the New York Mets came in 1963. After a disappointing tryout, Charley was on a bus to Tennessee, a slight detour on his way back to Montana. Red Sovine had told him when he was ready to pursue a singing career to stop by Cedarwood Publishing, a company that booked Sovine’s shows. While Charley was visiting Red, he had the opportunity to meet Jack Johnson—a man who was on a mission—to find a promising black country music singer. Charley recorded a couple of songs before heading back to Montana.

It would be 1965 before any significant progress was made. Charley and Rozene returned to Nashville. Soon Charley met “Cowboy” Jack Clement through Jack Johnson. At his request, Charley recorded two songs, The Snakes Crawl at Night and Atlantic Coastal Line. The recordings were sent to the people in Nashville, but the response they hoped for did not come.

A connection with Chet Atkins, a guitarist who was moving up the ladder with RCA records, was a turning point for Pride. Atkins not only encouraged and backed him but signed him with the RCA label. “Atkins took Charley under his wing, nurtured his talent, and spearheaded a shrewd promotional campaign that addressed the racial challenges of mid-1960s America.”

Charley Pride’s records caught hold in the country music world in 1967. From that year through 1987, record sales worldwide ranged in the tens of millions. He had 30 number one hits and 52 Top 10 Billboard singles. His many accolades include the Hollywood Walk of Fame Star received in 1999 and three GRAMMY awards and a Recording Academy Lifetime Achievement Award. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000. The years of listening to the Grand Ole Opry show came full circle. In 1993, Charley Pride was the first African American to be inducted into the Grand Ole Opry. He was also a businessman who invested in real estate and created an artist booking and management company called Chardon.

Mississippi Honors Pride

Pride’s first public concert in Mississippi was in May 1971 – a sold-out show at Delta State University. On March 29, 2011, the small town of Sledge and the state of Mississippi established a road marker, making it a part of the Mississippi Country Music Trail—established in 2009. The recognition of Charley Pride at age 73 also included renaming a portion of Highway 3 from Sledge to Tutwiler, now known as the Charley Pride Highway.

According to an article in the April 2011 issue of Taste of Country, Pride said, “I am completely honored and humbled by this recognition. It’s a wonderful feeling. Who’d have thought that a kid who walked four miles to school and back every day would ever get such a tribute?”

People around the world continue to enjoy his music. For Mississippians, we take pride in knowing that Charley Pride’s humble beginnings and love for country music started here. The song Mississippi Cotton Picking Delta Town (1974, written by Harold Dorman and George Gann) reflects his upbringing in Sledge.

Charley Pride died on December 12, 2020, from complications due to COVID-19. He was 86 years old.

Want to learn more about the life of Charley Pride? Read his autobiography, Pride: The Charley Pride Story, written with Jim Henderson, or visit Pride’s website: Charley Pride.

Mississippi

Minor earthquake recorded in Mississippi on Thanksgiving

MADISON COUNTY, Miss. (WJTV) – A minor earthquake was recorded in Mississippi early Thanksgiving morning.

According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the 2.5-magnitude earthquake occurred southeast of Canton near the Ross Barnett Reservoir around 1:48 a.m. on Thursday, November 28.

Officials with the Michigan Technological University said earthquakes below 2.5-magnitude are “generally not felt.” So far, there are no reports of any damage in Madison County.

The last earthquake that occurred in Madison County was a 2.8-magnitude earthquake in 2019.

Mississippi

Thanksgiving on Mississippi Public Broadcasting Think Radio, set to air on Thursday, November 28th

MISSISSIPPI (KTVE/KARD) — For Thanksgiving, on Thursday, November 28, 2024, the Mississippi Public Broadcasting Radio will air a special programming.

Photo courtesy of Mississippi Public Broadcasting

According to officials, “Turkey Confidential” and “Feasting with the Great American Songbook: An Afterglow Thanksgiving Special” will run from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Francis Lam will be taking calls and help those in need of Thanksgiving cooking tips for the biggest cooking day of the year.

According to officals, “Feasting with the Great American Songbook: An Afterglow Thanksgiving Special” will explore classic jazz and popular songs about food by singers like Louis Armstrong, Louis Jordan, and Fats Waller, perfect for listening while sitting at the table.

Mississippi

Southeast Mississippi Christmas Parades 2024 | WKRG.com

MISSISSIPPI (WKRG) — It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas on the Gulf Coast and that means Santa Claus will be heading to town for multiple parades around the area.

WKRG has compiled a list of Christmas parades coming to Southeast Mississippi.

Christmas on the Water — Biloxi

- Dec. 7

- 6 p.m.

- Begins at Biloxi Lighthouse and will go past the Golden Nugget

Lucedale Christmas Parade

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoTrump nominates Dr. Oz to head Medicare and Medicaid and help take on 'illness industrial complex'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoInside Elon Musk’s messy breakup with OpenAI

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoHoliday gatherings can lead to stress eating: Try these 5 tips to control it

-

Health3 days ago

Health3 days agoCheekyMD Offers Needle-Free GLP-1s | Woman's World

-

Science2 days ago

Science2 days agoDespite warnings from bird flu experts, it's business as usual in California dairy country

-

Technology1 day ago

Technology1 day agoLost access? Here’s how to reclaim your Facebook account

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoAlameda County child believed to be latest case of bird flu; source unknown

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoBehind Comcast's big TV deal: a bleak picture for once mighty cable industry