Louisiana

Louisiana’s Creole Culture Extends Far and Wide

Language experts estimate as many as 10,000 people still speak the French-based language Louisiana Creole.

In addition, many others in New Orleans and across the southern U.S. state consider themselves part of the culture that draws tens of thousands of people to events. The celebrations include autumn’s Festival Acadiens et Creoles, summer’s Creole Tomato Festival, and spring’s Tremé Creole Gumbo & Congo Square Rhythms Festival.

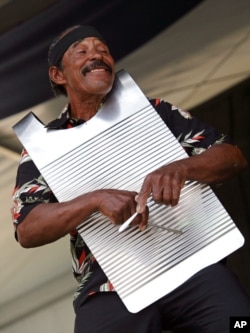

But for locals and visitors alike, everyday evidence shows how strong Creole culture is in Louisiana. The state’s performance spaces and airwaves are often filled with the driving, rhythmic sound of zydeco and other Creole and Cajun music. Louisiana’s restaurants offer dishes with rich, complex flavors including gumbo, hot sausage, red beans and rice, and shrimp étouffée.

“To celebrate Creole culture is to wake up and live in New Orleans,” said Christina Bragg. She is a member of the Mahogany Blue Babydolls, a parade group for Black and mixed-race women.

“Celebrating Creole is celebrating our day-to-day lives. The food we eat. The music we dance to. The way we gather with friends to parade during Mardi Gras,” she said. “Every day I open my eyes and breathe, it’s a celebration of Creole culture, because that’s who I am.”

Difficult to define

So, what is Creole?

“It’s food, it’s music, it’s architecture, it’s style and it’s traditions,” Mona Lisa Saloy told VOA. “There are millions of Creole people in countries across the world…we are all so much more alike than we are different. We create beautiful cultures everywhere we go, and I think that’s evident here in Louisiana.”

Saloy is the writer of the poetry collection Black Creole Chronicles and served as Louisiana’s poet laureate from 2021 to 2023. She said Creole cultures all over the world have similarities to Louisiana’s.

“Architectural styles common in New Orleans like the Creole Cottage or the Shotgun home can be found in other places with Creoles, such as in other parts of the American South and the Caribbean,” she said. “Much of our music derives from the rhythms of Africa and the Caribbean, as does much of our food — elements of gumbo such as the long rice and okra, for example, or the prevalence of beans.”

How the word “Creole” is defined changes from place to place and person to person.

The word “Creole” is believed to have come from the Portuguese word crioulo, which developed from the Latin word for “to create.” Some say it was used in the European slave trade to describe a slave born in the New World and not in Africa. The word took on different meanings in different places. Creole in much of Africa and part of the Caribbean, for example, came to mean people of mixed ethnic or racial backgrounds.

In Louisiana, the definition has changed over the years.

“Here, the definition kind of depends on who you ask,” said Vance Vaucresson. He is a New Orleans-based Creole and owner of a local restaurant, the Vaucresson Sausage Company.

“I prefer an inclusive definition,” he said. “By that definition, anyone born in Louisiana could be Creole. During our colonial era, it was meant to differentiate people born in the Americas — usually of French, Spanish or African descent — from those born in Europe or Africa.”

Describing his definition, Vaucresson added: “…it doesn’t matter. If you’re born here and embrace the culture, you can be Creole.”

In Louisiana of the 1700s and 1800s, the more inclusive definition was possibly the most accepted. White people with European ancestry were just as likely to call themselves Creole as mixed-race people of African ancestry.

White Creoles claimed the term because it set them apart from settlers who were coming from Northern states after The Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803. Mixed-race Creoles, too, claimed the term because it differentiated them from enslaved people.

Don Vappie is a Creole jazz musician in New Orleans. He described the idea of Creole before the Civil war as organized into three levels. “It was more of a three-tier racial hierarchy here, instead of the two-tiered Black-or-white experienced elsewhere in the U.S,” he said.

After the American Civil War, however, many of these differences in New Orleans disappeared.

“Creole or not, white people had more in common with white people and Black people had more in common with Black people,” Vappie told VOA.

Saloy believes Creole is firmly connected to African culture and should stay that way.

“The ingredients in our food, the rhythm in our music and dance, the details in our architecture — it’s all connected to West African culture,” she said, “That’s our heritage.”

I’m Caty Weaver. And I’m Faith Pirlo.

Matt Haines reported this story for VOANews. Caty Weaver adapted it for Learning English.

_______________________________________________

Words in This Story

rhythmic –adj. having a regular sound or movement

dish –n. a kind of food that is prepared in a particular way

Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday) –n. the Tuesday before the Catholic Lent religious observance

style –n. a particular way of designing something, doing some activity, or behaving

architectural –adj. related to the design of buildings

derive –v. to come from

prevalence –n. something that is widespread or usual

era –n. a period of time

tier –n. a level, especially one in an organization or a group

hierarchy –n. a system in which things are ordered by importance or status

ingredient –n. a material that is used to make something, especially food

Louisiana

Louisiana crawfish harvest down as much as 90% in shortage that could cripple industry for years

Louisiana experts fear that up to 90% of farm raised crawfish won’t make it after last year’s drought and this year’s late rains. The average price for a pound has already tripled.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture approved emergency financial relief for struggling crawfish farmers and fisherman for a 2024 harvest that is down 50-90% across Louisiana, according to the Louisiana State University Agricultural Center. However, the cash might not be enough to save next year’s season.

“Louisiana’s crawfish aquaculture industry will experience impacts from the 2023 drought for several seasons before an economic recovery is complete,” wrote the Ag Center’s Greg Lutz on TheFishSite.com. “Should drought conditions return before that takes place, the industry will be drastically transformed from the one we have come to know.”

Crawfish season is winding down across Louisiana, which produces about the majority of the nation’s crawfish every year, according to the Louisiana Crawfish Promotion and Research Board. Just in time for the summer heat, the mudbugs will burrow into the mud to spawn. But last year, a series of weather and climate disasters killed many. The high mortality rate of the crawfish meant fewer seeds for next year’s crop.

File: Boiled crawfish.

(Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group / Getty Images)

Drought, lack of rain, freeze took toll on crawfish

A historic drought in 2023, along with record summer heat, dried out the mud by late July through September when crayfish burrow into mud to spawn. They stay put until late fall when the usual heavy rains soften the plugs of clay soil that the moms carefully built to seal in the water, according to Lutz.

“The mama crawfish don’t come out until they hear the thunder,” wrote Lutz.

Rain is usually not an issue for hurricane-prone Louisiana.

However, the mud dried up and was too hard for mothers and babies to dig out of. Trapped moms resorted to eating their young or starving, according to a Food and Wine report. Many suffocated because their gills dried up after cracks formed in the mud, allowing in dry air.

SEE THE INVASIVE, AUSTRALIAN CRAWFISH DISCOVERED IN TEXAS

The animals that did survive were very small from lack of food. A January cold snap also stunted growth and killed off much of their food source. Both farm and wild-raised crustaceans were too small to sell. Producers reported no young crawfish in their ponds until early December, when farmers would begin to see harvestable animals in a normal year, according to the Ag Center.

“Looks like we a little less than 50% of the catch up until the end of April,” rice and crayfish farmer Paul Zaunbrecher told the Ag Center. “The revenue is probably 75% of what it was last year. So the price has made up for it somewhat.”

He is talking about a four-times price hike at the height of the season for a pound of boiled crawfish. FOX Weather checked prices and found they had soared to $16 per pound when, a year earlier, one pound went for $4-$5.

Some farmers abandoned the land

Another part of the problem is that many farmers chose not to flood their crayfish grounds. Zaunbrecher was just one of the many farmers to abandon acres.

File: Farmer Chad Hanks walks by dry cracked earth on his farm where he usually grows crawfish on October 10, 2023, in Kaplan, Louisiana.

(Getty Images)

“Some ponds never came into production because of the lack of crawfish or the inability to flood the ponds due to surface water issues,” the Ag Center’s Kenneth Gautreaux said in a video. “Some farmers feel that they were fortunate to catch what they could.”

The state only saw 44% of its normal rainfall from May-October 2023, and the average high was 3 degrees warmer than average. Harvesting fresh water came at a premium, and the Mississippi River hit record low levels, allowing salt water to enter from the Gulf of Mexico.

“As drought conditions intensified going into the autumn of 2023, it became apparent that many producers in the southwestern region of the state, who normally rely on surface water from natural watersheds and irrigation canals, would be unable to flood their ponds at all, due to excessive salinity caused by saltwater intrusion,” Lutz wrote. “Many producers in other regions were also unable to flood their ponds due to low water levels.”

SALT WATER THREATENS LOUISIANA DRINKING WATER SUPPLY AMID MISSISSIPPI RIVER DROUGHT

File: The sun sets over a field with crawfish traps near Crowley.

(Jon Shapley/Houston Chronicle / Getty Images)

The Ag center estimated the potential losses to be about $140 million to the state’s $230 million a year crawfish industry. The crawfish add $500 million to Louisiana’s economy and employ about 7,000 people.

Industry hurt for years to come

This season’s losses will mean losses next year, too.

“Crawfish have a cycle, and at the end of the season, typically, around June, there’s still a lot of crawfish left in the ponds,” Laney King of The Crawfish App told FOX Weather in an earlier interview. “We call this our carryover crawfish crop, and we rely on these carryover crawfish to then reproduce and create the next season’s crop.”

Lutz worries that mature crawfish stock will be hard to come by at any price. He estimates that the state would need about 1.5 billion pounds of mature stock to reestablish what was lost, along with the usual stock for farms that rotate between rice and crawfish. The state only harvests 100-120 pounds in an average year, according to Michigan State University.

HOW TO WATCH FOX WEATHER

File: Boiled crawfish.

(Jeff Greenberg/Universal Images Group)

Several lawmakers made appeals to the government early in the year. The governor issued a disaster declaration for the industry in early March, which allowed the Small Business Administration to make low-interest federal disaster loans available.

“Louisiana’s extreme drought conditions have affected our farmers, our economy, and our way of life,” Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry said in a statement. “All 365,000 crawfish acres in Louisiana have been affected by these conditions. That is why I am issuing a disaster declaration. The crawfish industry needs all the support it can get right now.”

The USDA waited months to amend the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybee and Farm Raised Fish Program to open funds to crayfish farmers. The last time crayfish producers were included was due to a deep freeze in 2021, according to Seafood Source.

About 85% of the state’s crawfish is farmed. None of the state is currently in drought.

Louisiana

Louisiana moves to make abortion pills a controlled substance

Outlawing abortion is only a first step for some conservative lawmakers, who keep dreaming up increasingly invasive schemes to ferret out and punish anyone trying to circumvent these bans. The latest example of this comes from Louisiana, where House lawmakers voted this week to make the abortion-inducing drugs mifepristone and misoprostol Schedule IV controlled substances.

That would make possession of these drugs a crime—punishable by a mandatory minimum prison sentence of one year and up to five years incarceration and a fine of $5,000—unless they were “obtained directly or pursuant to a valid prescription” for something other than abortion.

The alleged rationale for this bill is especially insane. State Sen. Thomas Pressly (R–Shreveport) brought in his sister, Catherine Pressly Herring, to testify about how her husband secretly slipped her abortion drugs when she was pregnant. “I share my story because no one should have abortion pills weaponized against them,” Herring said at an April hearing.

But administering abortion pills is already illegal in Louisiana, where abortion is banned with few exceptions. The state wouldn’t need a new law designating them a controlled substance in order to punish her husband’s alleged deception.

There are also ways authorities could write a law to more narrowly target such behavior—which is in fact what Sen. Pressley is trying to do with Senate Bill (SB) 276, the larger bill to which the controlled substance change is attached. SB 276 “creates the crime of coerced criminal abortion by means of fraud to prohibit a third-party from knowingly using an abortion-inducing drug to cause, or attempt to cause, an abortion on an unsuspecting pregnant mother without her knowledge or consent,” per the state legislature’s website.

The True Target: Doctors and Pharmacists?

With or without this new crime, there is no reason the state needs to make abortion pills a Schedule IV controlled substance in order to target someone who secretly slips them into his pregnant wife’s drink. But this is a common tactic used by lawmakers trying to grant the state new power: using an extreme and sympathetic example of wrongdoing to justify a wide-reaching change that will be used in matters way beyond that example.

In this case, the most likely target is doctors who prescribe mifepristone and misoprostol.

Both drugs have multiple uses beyond inducing abortions. In fact, misoprostol originally gained traction as an anti-ulcer drug. It also has a number of obstetric uses, including inducing labor and treatment after a miscarriage. And Mifepristone is prescribed to people with Cushing syndrome and uterine leiomyomas.

Prescribing mifepristone or misoprostol for non-abortion reasons is still legal in Louisiana and other states where abortion is banned. But abortion foes worry some medical professionals may use this to covertly prescribe it for abortions.

If these drugs are controlled substances, doctors will have to have a special Drug Enforcement Administration license to prescribe them and the state will be able to track when they’re prescribed, to whom, and at what pharmacy these prescriptions are filled.

Effect on Health Care

“Louisiana law typically categorizes medications, such as opioids, as Category IV drugs because they are addictive and thus have a high potential for abuse,” notes University of California, Davis School of Law professor Mary Ziegler at MSNBC:

To prescribe such drugs, physicians in the state need a special license, and the state tracks the patient, physician and pharmacy involved in each prescription. Therein lies one of the primary functions of the law: The state has had a hard time enforcing its abortion ban in part because it is hard to identify when and how pills change hands. At least when a prescription originates in state, this bill might give Louisiana prosecutors an extra edge in identifying people to prosecute.

The bill explicitly exempts pregnant women who have misoprostol or mifepristone for their own use from prosecution—another example of the weird paternalism involved in anti-abortion laws. I’m certainly glad most states don’t want to criminalize women for attempting or having abortions, but it’s also somewhat crazy to act like the woman here is not culpable for her actions but someone who helped her get abortion pills is.

While the law might not result in sending women to prison over abortion drugs, it could be bad for the health of women with miscarriages and other obstetric issues for which misoprostol and mifepristone are prescribed, as well as for people with ulcers and Cushing’s disease.

Doctors are likely to be leery of prescribing these medications for people who need them, much in the same way that crackdowns on pain pills and ADHD medications have harmed people who legitimately need these medicines for health conditions.

What’s Next

The bill seems likely to pass.

Louisiana’s Senate passed SB 276 without the controlled substances amendment by a unanimous vote back in April.

It defines the crime of coerced abortion by means of fraud as “a person knowingly and intentionally engages in the use or attempted use of an abortion-inducing drug on a pregnant woman, without her knowledge or consent, to cause an abortion,” and prescribed a punishment of five to 10 years in prison and a fine of up to $75,000 if the woman was less than three months pregnant and 10 to 20 years in prison and a fine of up to $100,000 if the pregnancy was further along than three months.

It also amends the state’s prohibition on “criminal abortion by means of abortion-inducing drugs” to include not just causing an abortion by “delivering, dispensing, distributing, or providing a pregnant woman with an abortion-inducing drug” but also with attempting to cause an abortion by these means.

SB 276 passed the House, with the amendment, on Tuesday, by a vote of 64-29. This version contains an amendment declaring “any material, compound, mixture, or preparation containing any detectable quantity of mifepristone or misoprostol” to be a Schedule IV controlled substance in Louisiana.

The measure now goes back to the Senate for another vote.

More Sex & Tech News

• Florida is micromanaging what massage therapists can wear in the name of “cracking down on human trafficking.” Under a new law signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis last week, their clothing must be “fully opaque and made of non-translucent material.” The law also stipulates that window coverings at massage businesses must allow in 35 percent of light. This is the kind of law that will do naught for “human trafficking” or labor exploitation, of course. But it does give authorities more pretense to investigate, sanction, and shut down massage businesses of the sort disfavored in many communities.

• The Woodhull Foundation and the Electronic Frontier Foundation are urging the U.S. Supreme Court to find Texas’ age-verification mandate (part of H.B. 1181) unconstitutional.

• California is the latest state to advance an age verification measure.

• Washington and Silicon Valley are gearing up for a war over AI.

Today’s Image

Louisiana

‘What they’re doing is not oversight’: Louisiana fails to closely monitor schools’ special education, audit finds

The Louisiana Department of Education failed to protect the rights of students with disabilities by making sure schools follow federal law, according to a new audit that says hundreds of schools were allowed to go years without state inspections.

More than 40% of the state’s school systems went at least seven years without the department conducting an inspection of their special-education services, according to a Louisiana Legislative Auditor report released last week. Instead, the department asked most of those school districts and charter schools to complete “self-assessments,” documenting times they failed to comply with federal law and creating their own improvement plans.

While the state’s monitoring appears to meet federal requirements, it is not robust enough to ensure that students receive the special education services they are entitled to under the law, according to the audit, which examined the department’s special-education monitoring from 2015-2022.

Due to budget cuts during that period, the department slashed its special-education staff by nearly 70%. Today, six employees are responsible for monitoring special-education compliance in the state’s nearly 190 school districts and charter schools.

“What they’re doing is not oversight,” said Kathleen Cannino, a special education advocate whose child has a disability. “Without that monitoring, these kids are lost.”

Education Department officials said the agency’s special-education monitoring meets federal requirements and includes oversight beyond what is highlighted in the audit. Still, they said they agree with some of the report’s recommendations and have made changes and plan to hire more monitors if the state provides funding.

Meredith Jordan, the department official who oversees special education, said she welcomed the audit as part of the department’s commitment to “continuous improvement.”

“We want more on-site, boots-on-the-ground monitoring” of schools’ special education programs, she said. “We’ve already taken steps to address that.”

What does federal law require?

Nearly 90,000 students in Louisiana’s public schools, or about 13% of the student population, have a disability.

Under federal law, public schools must provide those students with special education services that meet their individual needs. Louisiana received about $228 million in federal aid last year for special education. In exchange, the state must ensure that schools comply with federal law.

The state employs a ranking system to monitor special education. Using test scores and other performance measures, school systems are ranked on their likelihood of not meeting students’ needs. Lower-risk systems are asked to assess their own special-education programs, while higher-risk systems receive state inspections.

During the seven-year period ending in 2022, the department conducted just 10 on-site inspections. In those reviews, state monitors visit schools to observe special education programs in action, meet parents and interview staffers.

Only nine of the state’s 100 school districts and charter schools received on-site inspections during the years covered by the audit.

Mary Jacob, executive director of Families Helping Families of Greater New Orleans, a resource center for parents of children with disabilities, said in the past she helped arrange parent meetings during the state’s on-site inspection.

“The districts took it very seriously,” she said, adding that monitors often spent several days in a district conducting interviews and reviewing student files. “If there was something in the file that looked a little funny, we could go to the school and see what was happening.”

Now that such inspections are rare, schools face less pressure to closely follow special-education laws, Jacob said.

“They know they’re not going to get in trouble,” she said, “so why bother?”

Many districts not inspected at all

According to the audit, another 48 school systems were subjected to “desk reviews,” in which department staffers examine school files and data remotely. Schools have 30 days to provide the requested documents. In a survey of nearly 100 special-education administrators conducted by the Legislative Auditor, about one in four said there is a risk schools will alter requested documents before sending them to the state.

Still, the audit said remote or in-person inspections are essential for monitoring schools’ compliance with federal law, the audit said. They reveal whether schools properly evaluate students for disabilities, create special-education plans for each student and provide legally mandated services — “activities not included in any other type of monitoring,” according to the audit.

Yet 43 of the 100 school districts and charter schools did not receive either type of inspection from 2015-2022. Most of those school systems, which include 580 schools and nearly 36,000 students with disabilities, were asked to complete self-assessments, the audit found.

The districts chose which files to review and noted any violations of special-education law that they found. The Education Department did not track those self-reported violations, the audit said.

Cannino said that it often falls on parents and advocates like her to ensure that schools provide students with their mandated special-education services.

“You have to do it every single year because there’s no monitoring,” she said. “And it’s exhausting.”

Other findings from the audit include:

- The state Education Department received nearly $19 million in federal aid to oversee special education in fiscal year 2023, yet it spent only $612,000 on school monitoring.

- The department focused its oversight on Orleans Parish following a federal lawsuit that alleged the state failed to properly monitor special education in that parish. From 2015-2022, more than 60% of state inspections targeted Orleans Parish schools, even though they serve just 7% of the state’s students with disabilities.

- The department does not track “informal removals,” when students are kept out of school due to their behavior but are not suspended. Such removals, which includes repeatedly asking parents to pick up students who act out, can allow schools to skirt protections for students with disabilities. Under federal law, if a student is suspended or expelled for more than 10 days due to behaviors caused by a disability, the school must come up with a behavior plan for that student.

Department officials said informal removals are difficult to track because they are not clearly defined by law.

The officials also said Louisiana’s special-education monitoring currently adheres to federal guidance issued in 2023, which require states to review each school district every six years. The department also reviews school performance and spending data annually, the officials added.

The department plans to hire six additional monitors, doubling the size of that team, if the Legislature includes the requested funding in the upcoming budget, the officials said. They added that the department has already improved its system for responding to parents’ special-education complaints, which was the subject of a Legislative Auditor report last fall.

“We’ve continued to work alongside stakeholders to engage in continuous improvements for students with disabilities across the state,” Jordan, the department’s executive director of diverse learners, said in a statement. “Together, we have made several policy, procedural, and staff changes over the past year.”

But advocates who have long demanded better special-education monitoring said the department has been slow to make changes.

“This audit was validation of what we’ve been saying for three years in private meetings” with state officials, said Jodi Rollins, an advocate and parent of three children with disabilities, including a son who will soon finish high school. “My son is running out of time.”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNevada Cross-Tabs: May 2024 Times/Siena Poll

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPro-Palestinian university students in the Netherlands uphold protest

-

Politics1 week ago

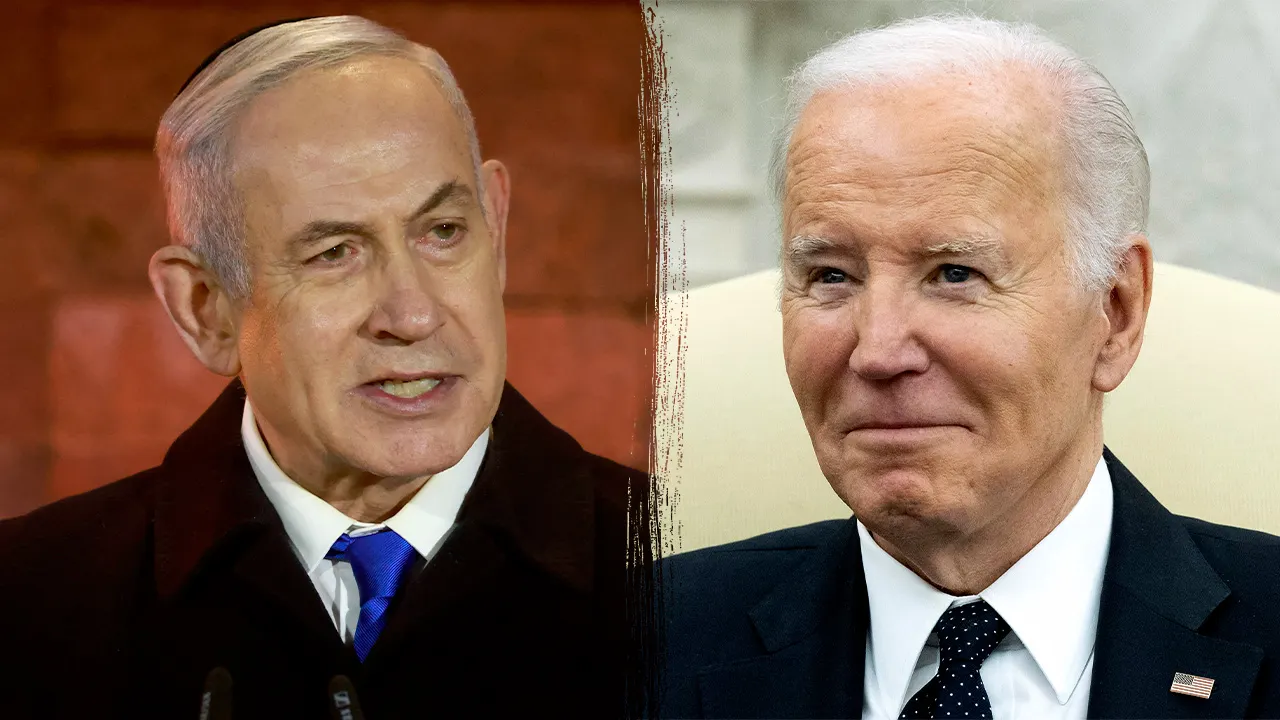

Politics1 week agoWhite House walks diplomatic tightrope on Israel amid contradictory messaging: 'You can't have it both ways'

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoSouthern border migrant encounters decrease slightly but gotaways still surge under Biden

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDem newcomer aims for history with primary win over wealthy controversial congressman

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoSlovakia PM Robert Fico in ‘very serious’ condition after being shot

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNY v. Trump trial resumes with 'star witness' Michael Cohen expected to take the stand

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoReports of Biden White House keeping 'sensitive' Hamas intel from Israel draws outrage