Science

Robert H. Grubbs, Caltech Nobel Prize winner who revolutionized green chemistry, dies

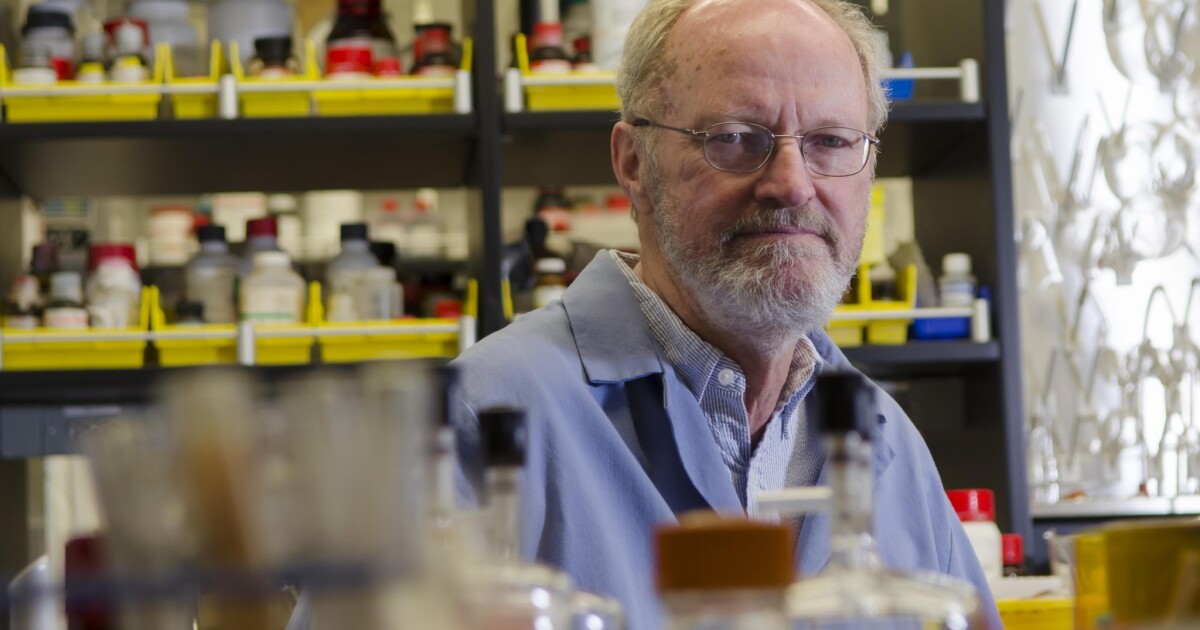

Robert H. Grubbs, the Caltech Nobel Prize winner whose strategies of breaking up molecules and rebuilding them in response to specification revolutionized the sector of natural chemistry, has died at 79.

Exploiting a course of often known as metathesis, during which carbon compounds trade components with each other, Grubbs confirmed how one can create a broad vary of latest merchandise, from environmentally pleasant plastics to resins to prescribed drugs.

His discoveries constructed on the work of two different scientists, Yves Chauvin of France and Richard Schrock of MIT, with whom he shared the $1.3-million Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2005. “He was the one who took what I did and turned it into one thing sensible,” Schrock mentioned on the time.

A serious advantage of Grubbs’ course of was that it minimized wasteful and dangerous byproducts of chemical reactions, an necessary advance within the discipline of what’s now known as inexperienced chemistry. “Bob’s power as a scientist was his creativity,” mentioned Dennis Dougherty, the Norman Davidson Management Chair in Chemistry at Caltech. “He was essentially the most inventive chemist I ever interacted with.”

Grubbs, who was admired as a lot for his heat and private simplicity as for his achievements, died of a coronary heart assault Dec. 19 on the Metropolis of Hope hospital in Duarte, the place he was being handled for lymphoma, his son Barney mentioned.

Robert H. Grubbs was born Feb. 27, 1942, in a farmhouse his father constructed close to Possum Trot, Ky. The center baby between two sisters, he described his upbringing as one thing out of a rural American novel of manners, with a supportive prolonged household of aunts, uncles and grandparents, a lot of them farmers in tobacco nation. His mom taught faculty for 35 years whereas his father labored as a mechanic for the Tennessee Valley Authority.

A lanky boy — he stood 6 toes, 6 inches in maturity — he was desirous about all issues mechanical; any cash earned was spent on nails as a substitute of sweet. Having spent his summers in farm work and development, he enrolled on the College of Florida as an agricultural chemistry main. There, he landed a summer season job analyzing steer feces.

A good friend working in a chemistry lab saved him from a profession learning animal matter, Grubbs mentioned, by inviting him to assist out at night time. “I discovered that natural chemical compounds smelled a lot better than steer feces and that there was nice pleasure in making new molecules,” he wrote later.

Natural compounds based mostly on advanced preparations of carbon atoms are the idea of all life that we all know. Studying how these compounds react on a molecular stage, and how one can adapt them to new makes use of, fascinated Grubbs as a scholar. “Constructing new molecules was much more enjoyable than constructing homes,” he mentioned.

He earned his bachelor and grasp’s levels on the College of Florida, then acquired his doctorate from Columbia College, the place he met and married his spouse, Helen O’Kane, who turned a particular schooling instructor. He spent a yr at Stanford College as a Nationwide Institutes of Well being fellow earlier than becoming a member of the school of Michigan State College in 1968. A decade later, he was employed by Caltech, the place he turned the Victor and Elizabeth Atkins Professor of Chemistry in 1990.

When his profession started, “organometallic chemistry was in its infancy and it supplied a fertile discipline for a mechanistic chemist,” Grubbs mentioned. He turned significantly desirous about metathesis, a phrase that means altering locations, involving chemical reactions during which two carbon-based molecules trade fragments underneath the affect of a 3rd molecule, often known as a catalyst. On this manner, bits of molecules will be selectively stripped out and changed with items from one other compound.

The pure course of was first noticed within the Nineteen Fifties within the petrochemical business, however scientists didn’t know what was happening, and even how one can use it. Chauvin supplied the primary theoretical mannequin in 1970, suggesting that the method is initiated by a household of chemical compounds known as metallic carbenes, during which a metallic atom is double-bonded to a carbon atom. In what has been likened to a dance, the metal-carbon double-bond binds to a carbon-carbon bond in a goal molecule, forming a hoop of 4 atoms. The 4 then separate into new couplets, with totally different companions.

On the Royal Swedish Academy of Science’s information convention asserting the Nobel award in 2005, the method was demonstrated by two dancing {couples}. All 4 dancers then joined palms earlier than separating once more, with every member dancing off with a brand new accomplice.

After Chauvin’s report, Schrock started looking for a catalyst that might perform the response in a predictable manner, lastly deciding on molybdenum and tungsten. The issue was that these metals weren’t steady in air and had been incompatible with many different compounds.

In 1992, Grubbs solved the issue through the use of ruthenium as a catalyst. It proved to be rather more steady and might be utilized in a wide range of substrates, together with water and alcohol. A type of compounds turned often known as the “Grubbs catalyst” and was the usual towards which all others had been measured.

To Grubbs, it was a shock the method labored. “Carbon-carbon double bonds are normally one of many strongest factors within the molecule,” Grubbs advised the New York Instances. “To have the ability to rip them aside and put them again collectively very cleanly was an entire shock to natural chemists.”

His work was tailored in a brand new household of custom-built compounds with specialised properties, akin to medicine for varied illnesses, plastics made out of vegetable oils, slightly than petroleum, and herbicides.

Grubbs’ unfussy method to his accomplishments revealed itself maybe greatest in his response to being named a Nobelist. “I had simply opened a bottle of fine port,” he advised the Los Angeles Instances’ Tom Maugh by cellphone from New Zealand, “so I continued consuming it.”

In his free time, he turned a climber, scaling rocks in Joshua Tree and Yosemite, and late in life adopted fly-fishing as a passion, his son mentioned.

Over his profession, Grubbs suggested and mentored greater than 100 doctoral candidates and nearly 200 postdoctoral associates. He additionally co-founded a number of firms, together with Materia Inc. of Pasadena, which held the rights to his catalysts.

“Bob was an inspiration to Caltech colleagues and to scientists all over the world, for his human qualities as a lot as for his pathbreaking contributions to analysis and society. We’ll keenly miss his knowledge and imaginative and prescient,” mentioned Caltech President Thomas F. Rosenbaum.

Moreover the Nobel Prize, Grubbs was the recipient of the Benjamin Franklin Medal from the Franklin Institute, the Arthur C. Cope Award from the American Chemical Society and the Gold Medal from the American Institute of Chemists. He was a member of the Nationwide Academy of Sciences, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a member of the Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels. He acquired honorary levels from, amongst others, the Georgia Institute of Know-how, the College of Crete in Greece, the College of Warwick in the UK, and Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen College in Germany.

He authored greater than 400 papers and held 80 patents.

Grubbs is survived by his spouse; kids Kathleen, Brendan and Barney; 4 grandchildren; and two sisters.

Johnson is a former Instances employees author. Workers author Gregory Yee contributed to this report.

Science

Why the U.S. surgeon general wants cancer warning labels on alcoholic drinks

Alcoholic drinks are a leading cause of cancer and should carry a warning about that risk on their labels, the U.S. surgeon general said Friday.

Alcohol is a factor in nearly 100,000 newly diagnosed cancers each year and roughly 20,000 deaths from the disease, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy said in an advisory intended to focus the public’s attention on the health risk. By comparison, traffic accidents tied to drinking kill about 13,500 Americans each year.

“Alcohol consumption is the third leading preventable cause of cancer in the United States, after tobacco and obesity,” the 22-page advisory said. “While scientific evidence for this connection has been growing over the past four decades, less than half of Americans recognize it as a risk factor for cancer.”

Labels on bottles and cans of alcoholic beverages already warn about drinking while pregnant. They also warn about drinking before driving or operating other machinery. In California, the voter-approved Proposition 65 also requires businesses that serve or sell alcoholic beverages to provide a warning about health risks, including cancer.

Any decision to update or expand the label would require congressional approval, an uncertain prospect. Murthy was appointed by President Biden, who has a little more than two weeks left in office. President-elect Donald Trump has picked Janette Nesheiwat, an executive at a New York-based chain of urgent care clinics, as his nominee for surgeon general.

Executives in the beer, wine and spirits industry said Friday that the scientific data linking alcohol to cancer are mixed.

Amanda Berger, senior vice president at the Distilled Spirits Council, noted that a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found that alcohol was associated with a higher risk of breast cancer but did not find such associations with other types of cancer.

That report also concluded that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with lower risks of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease, compared with never consuming alcohol.

“The current health warning on alcohol products has long informed consumers about the potential risks of the consumption of alcohol,” Berger said. “Many lifestyle choices carry potential risks, and it is the federal government’s role to determine any proposed changes to the warning statements based on the entire body of scientific research.”

The surgeon general’s advisory said that cancers of the colorectum, esophagus, liver, mouth, throat and larynx are all tied to drinking, as is breast cancer in women. The risk of developing breast, mouth or throat cancers may increase with less than one drink per day, it said.

(Office of the U.S. Surgeon General)

Yet more than half of Americans are unaware that their drinking behavior affects their cancer risk. A survey by the American Institute for Cancer Research found that 89% of Americans recognized that smoking causes cancer and 53% knew that obesity was a risk factor, but only 45% realized that alcohol could cause cancer as well.

Nearly half of alcohol-related cancers in the U.S. are breast cancers in women, according to a study published by the American Cancer Society. About 1 in every 6 female breast cancers is due to alcohol, and the disease accounts for about 60% of all alcohol-related cancer deaths in women.

As a result, drinking is a bigger cancer risk for women than men. In 2019, about 54,330 women were diagnosed with a cancer that resulted from drinking, as were roughly 42,400 men. About 60% of alcohol-related cancer deaths in women are due to breast cancer, while liver cancer and colorectal cancer are responsible for about 54% of alcohol-related cancer deaths in men.

For women who consume less than one drink a week, the absolute risk of developing an alcohol-related cancer is 16.5%. Having one drink per day increases that risk to 19%, and having two drinks each day raises it to 21.8%, according to the advisory.

For men, drinking once a week is tied to a 10% absolute risk of an alcohol-related cancer. That risk rises to 11.4% by having one drink per day, and to 13.1% by having two drinks per day, the advisory says.

The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer says alcohol is a Group 1 carcinogen, putting it in the company of tobacco, asbestos and ultraviolet radiation. The U.S. National Toxicology Program declared in 2000 that alcohol causes cancer in humans, and organizations including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, the American Cancer Society and the American Assn. for Cancer Research agree that at least seven kinds of cancer are related to drinking.

There is also evidence to suggest that drinking contributes to skin, prostate, pancreatic and stomach cancers, though more research is needed, the surgeon general’s advisory says.

Scientists first linked alcohol consumption to certain cancers nearly 50 years ago, and the evidence showing that drinking is a risk factor for at least seven types of cancer has grown since then, the advisory says.

For instance, an observational study of 28 million people in 195 countries and territories found that the more alcohol a person consumed, the higher their risk of cancer. A study involving more than 1 million women found that those who had up to 1 drink per day were 10% more likely to get breast cancer compared with those who abstained. Likewise, a study with 36,000 people found that those who consumed about a drink per day were 40% more likely to develop mouth cancer than people who didn’t drink.

Laboratory experiments have shown how alcohol leads to cancer.

When alcohol is metabolized in the body, it breaks down into a chemical called acetaldehyde that can attach itself to DNA. The resulting damage can trigger the uncontrolled cell growth that leads to cancer.

Drinking also creates unstable molecules called reactive oxygen species that can interfere with DNA, proteins and essential fats. They also increase inflammation, which makes the body more hospitable to cancer.

There is also evidence that alcohol fuels breast cancers by affecting levels of estrogen and other hormones, and that other kinds of carcinogens — such as those found in tobacco smoke — are more easily absorbed in the body when they are dissolved in alcohol.

The companies selling alcoholic beverages say they have long urged consumers to drink the beverages safely.

“The U.S. beer industry has been a champion of responsible consumption for decades,” a spokesperson for the Beer Institute said Friday. “We encourage adults of legal drinking age to make choices that best fit their personal circumstances, and if they choose to drink, to consume alcohol beverages in moderation.”

Dr. Laura Catena, a winemaker and physician, said that she would “welcome any kind of alert or communication from the surgeon general about the cancer risks of heavy alcohol drinking,” but that it shouldn’t go beyond the established science.

The American Assn. for Cancer Research says alcohol use is responsible for 5.4% of all cancer cases in the U.S. That makes it a bigger risk factor than exposure to UV radiation, poor diet, and infections from pathogens like hepatitis and the human papillomavirus. (For comparison, 19.3% of U.S. cancers are attributable to smoking, according to the association.)

Studies suggest that people who cut back on alcohol or eliminate it can reduce their risk of these cancers by 8%, and reduce their overall cancer risk by 4%.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans from the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services say there is no health reason for nondrinkers to start consuming alcohol. Those who do drink can minimize their risk by limiting their intake to no more than one drink per day for women and no more than two drinks per day for men.

A 5-ounce glass of wine, 12-ounce bottle of beer or 1.5-ounce tumbler of distilled spirits count as a single drink.

The surgeon general’s advisory says about 83% of alcohol-related cancer deaths occur in people who exceed those limits. But that means 17% of deaths were in people who engaged in moderate drinking.

Science

U.S. Surgeon General Calls for Cancer Warnings on Alcohol

Alcohol is a leading preventable cause of cancer, and alcoholic beverages should carry a warning label as packs of cigarettes do, the U.S. surgeon general said on Friday.

It is the latest salvo in a fierce debate about the risks and benefits of moderate drinking as the influential U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans are about to be updated. For decades, moderate drinking was said to help prevent heart attacks and strokes.

That perception has been embedded in the dietary advice given to Americans. But growing research has linked drinking, sometimes even within the recommended limits, to various types of cancer.

Labels currently affixed to bottles and cans of alcoholic beverages warn about drinking while pregnant or before driving and operating other machinery, and about general “health risks.”

But alcohol directly contributes to 100,000 cancer cases and 20,000 related deaths each year, the surgeon general, Dr. Vivek Murthy, said.

He called for updating the labels to include a heightened risk of breast cancer, colon cancer and at least five other malignancies now linked by scientific studies to alcohol consumption.

“Many people out there assume that as long as they’re drinking at the limits or below the limits of current guidelines of one a day for women and two for men, that there is no risk to their health or well-being,” Dr. Murthy said in an interview.

“The data does not bear that out for cancer risk.”

Only Congress can mandate new warning labels of the sort Dr. Murthy recommended, and it’s not clear that the incoming administration would support the change.

Still, President-elect Donald J. Trump does not drink, and his choice to head the Health and Human Services Department, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., swore off alcohol and drugs decades ago, and says he regularly attends AA meetings.

There is no question that heavy consumption is harmful. But supporters of moderate drinking — including makers of wine, beer and spirits, and some physicians and scientists — argue that a little alcohol each day may reduce cardiovascular disease, the No. 1 killer in the United States.

Newer scientific studies have criticized the methodology of earlier studies, however, and have challenged that view, which was once a consensus.

While most cancer deaths occur at drinking levels that exceed the current recommended dietary guidelines, the risk for cancers of the breast, the mouth and the throat may rise with consumption of as little as one drink a day, or even less, Dr. Murthy said on Friday.

Overall, one of every six breast cancer cases is attributable to alcohol consumption, Dr. Murthy said. More recent studies have also linked moderate alcohol consumption to certain forms of heart disease, including atrial fibrillation, a heart arrhythmia.

Two scientific reviews will be used to inform the updated recommendations about alcohol consumption in the federal dietary guidelines.

Five years ago, the scientific report that informed the writing of the 2020-2025 dietary guidelines acknowledged that alcohol is a carcinogen and generally unhealthy and suggested “tightening guidelines” by capping the recommendation for men at one standard drink, or 14 grams of alcohol a day.

When the final guidelines were drafted, however, there was no change in the advice that moderate drinking of up to two drinks a day for men was acceptable.

But the government acknowledged emerging evidence indicating that “even drinking within the recommended limits may increase the overall risk of death from various causes, such as from several types of cancer and some forms of cardiovascular disease.”

Since then, even more studies have linked alcoholic beverages to cancer. Yet any attempt to change the warning labels on alcoholic beverages is likely to face an uphill battle.

The current warning label has not been changed since it was adopted in 1988, even though the link between alcohol and breast cancer has been known for decades.

It was first mentioned in the 2000 U.S. Dietary Guidelines. In 2016, the surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs and health linked alcohol misuse to seven different types of cancer.

More recently, a scientific review of the research on moderate drinking, carried out under the auspices of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, was commissioned by Congress.

That analysis found a link between alcohol consumption and a slight increase in breast cancer, but no clear link to any other cancers. The report also revived the theory that moderate drinking is linked to fewer heart attack and stroke deaths, and fewer deaths overall, compared with never drinking.

The World Health Organization says there is no safe limit for alcohol consumption, however, and 47 nations require warnings on alcoholic beverages. But cancer is rarely mentioned.

To date, only South Korea has a label warning about liver cancer, though manufacturers can choose alternative labels that don’t mention cancer. Ireland is currently slated to introduce labels that say there is a “direct link between alcohol and fatal cancers” in 2026.

The industry has a strong history of fighting warning labels that mention cancer, and alcohol-producing nations have also challenged warning labels under international trade law.

Industry opposition led to the premature termination of a federally funded Canadian study of the impact of warning labels that mentioned cancer.

The surgeon general’s advisory provided a brief overview of research studies and reviews published in the past two decades, including a global study of 195 countries and territories involving 28 million people.

They all found that higher levels of alcohol consumption were associated with a greater risk of cancer.

Other studies looked at specific cancers, like breast cancer and mouth cancer, finding the risks increased by 10 percent and 40 percent, respectively, for those who had just one drink a day, when compared with those who did not drink.

The report described the biological mechanisms by which alcohol is known to induce cancerous changes at the cellular level.

The most widely accepted theory is that inside the body, alcohol breaks down into acetaldehyde, a metabolite that binds to DNA and damages it, allowing a cell to start growing uncontrollably and creating a malignant tumor.

Animal experiments have shown that rodents whose drinking water was spiked with either ethanol, the alcohol used in alcoholic beverages, or with acetaldehyde developed large numbers of tumors all over their bodies.

Research has shown that alcohol generates oxidative stress, which increases inflammation and can damage DNA.

It also alters levels of hormones like estrogen, which can play a role in breast cancer development, and makes it easier for carcinogens like tobacco smoke particles to be absorbed into the body, increasing susceptibility to cancers of the mouth and the throat.

The surgeon general’s report also goes into detail about the increase in risk associated with drinking, differentiating between the increases in absolute risk and in relative risk.

For example, the absolute risk of breast cancer over a woman’s life span is about 11.3 percent (11 out of 100) for those who have less than a drink a week.

The risk increases to 13.1 percent (13 of 100 individuals) at one drink a day, and up to 15.3 percent (15 of 100) at two drinks per day.

For men, the absolute risk of developing an alcohol-related cancer increases from about 10 percent (10 of every 100 individuals) for those who consume less than one drink a week to 11.4 percent (11 per 100) for those who have a drink every day on average. It rises to 13 percent (13 of 100 individuals) for those who have two drinks a day on average.

Many Americans don’t know there is a link between alcohol and cancer.

Fewer than half of Americans identified alcohol use as a risk factor for cancer, compared with 89 percent who recognized tobacco as a carcinogen, according to a 2019 survey of U.S. adults aged 18 and older carried out by the American Institute for Cancer Research.

Yet alcohol consumption is the third leading preventable cause of cancer, after tobacco and obesity, according to the surgeon general’s report.

Dr. Murthy said it was important to know that the risk rises as alcohol consumption increases. But each individual’s risk of cancer is different, depending on family history, genetic makeup and environmental exposures.

“I wish we had a magic cutoff we could tell people is safe,” he said. “What we do know is that less is better when it comes to reducing your cancer risk.”

“If an individual drinks occasionally for special events, or if you’re drinking a drink or two a week, your risk is likely to be significantly less than if you’re drinking every day,” he added.

Science

107 more women accuse former Cedars-Sinai physician of sexual misconduct

More than 100 women have filed a new lawsuit against obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Barry J. Brock and the facilities where he worked, claiming that Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and other medical practices knowingly concealed his alleged sexual abuses and medical misconduct.

The 107 new plaintiffs join 60 other former patients who have accused Brock in lawsuits last year of inappropriate and medically unjustifiable behavior that at times resulted in lasting physical complications.

Brock didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment Thursday.

Brock, 74, has previously denied all allegations of impropriety. The longtime OB-GYN was a member of the Cedars-Sinai physician network until 2018 and retained his clinical privileges there until mid-2024.

Cedars-Sinai “received numerous complaints regarding [his] sexually exploitative and abusive behavior, dating back several decades,” the lawsuit alleges. Nevertheless, “Brock has been allowed to continue injuring, exploiting, and abusing patients under the guise of medical care at Cedars-Sinai from 1979 through August of 2024,” the suit says.

A Cedars-Sinai spokesperson said that “the type of behavior alleged about Dr. Barry Brock is counter to Cedars-Sinai’s core values and the trust we strive to earn every day with our patients.”

“Dr. Brock no longer has privileges to practice medicine at Cedars-Sinai, and we have reported this matter to the California Medical Board,” the spokesperson said.

In July, Cedars-Sinai said it suspended Brock’s hospital privileges after receiving “concerning complaints” from former patients. His hospital privileges were terminated a few months later.

In the most recent suit, filed Dec. 27 in Los Angeles County Superior Court, former patients accuse Brock of groping their breasts and genitals unnecessarily under the pretense of legitimate medical examinations.

More than a dozen women say in the suit that Brock fondled their clitorises during exams and procedures. Three women alleged that Brock used examination instruments in inappropriate and violating ways, thrusting them in their bodies while at times making lewd comments.

Several said that he conducted vaginal examinations without wearing gloves, which the Federation of State Medical Boards lists as an example of sexual impropriety.

A woman who saw Brock once in 2015 when her regular doctor was unavailable asked why he wasn’t wearing gloves, the lawsuit states. Brock allegedly responded: “Your down there is much dirtier than my hands.”

Former patients allege in the latest suit that Brock’s frequent comments about their bodies or sexual desirability, often made during the middle of sensitive physical examinations, left them deeply uncomfortable. When one patient disclosed during a visit that she was a lesbian, the suit alleges, Brock replied, “Well, I can change that.”

Another woman said that she noticed photographs she had taken as a model on an exam room computer during one of her visits. “I was looking at your modeling pictures and take a look at this one. You can see your [vulva] right through the outfit,” Brock allegedly told her, using a crude term for female genitalia.

Multiple patients say in the lawsuit that Brock dismissed complaints of pain or medical concerns with sexually inappropriate comments. To a patient who told him that a pap smear was causing her pain, the lawsuit alleges, Brock made a comment about her sexual history and replied that she “should like it.”

Others said Brock’s care left them with lasting physical complications.

One woman said Brock delivered her baby in 2005 as the on-call doctor at Cedars-Sinai and proceeded to suture her perineal area after birth, a procedure he told her husband would leave the patient “like a virgin.” Two decades later, the woman still finds sexual intercourse painful as a result of the suturing, the suit alleges. Four other plaintiffs also reported lasting pain as a result of post-birth stitches Brock inserted after delivery.

Several patients allege in the suit that they reported their discomfort to office staff, nurses or other doctors, and received responses that suggested that his behavior was known to staff.

When one woman who saw Brock from 2002 to 2012 “would express to the nurses or other doctors that his behavior was rough and rude,” the lawsuit states, she “would be told, ‘That’s just how he is’ and ‘Don’t put much on it.’”

Another disclosed to a labor and delivery nurse that Brock had called her a crude name during one of her visits, the suit alleges.

The nurse responded “that she was not surprised, and implied that Brock had a reputation for making off colored remarks,” the suit states.

The lawsuit also names Beverly Hills OB-GYN and Rodeo Drive Women’s Health Center, where Brock worked after leaving the Cedars-Sinai physician network. Neither responded immediately to requests for comment on Thursday.

At the time Cedars suspended Brock’s privileges, a spokesperson for the medical center said that privacy laws prohibited it from confirming the existence of any patient complaints or disciplinary action taken against Brock before 2024.

Brock, who retired from medicine in August, said previously that he surrendered his privileges without any “hearing on the merits” of the allegations under investigation.

The plaintiffs who have brought suit against Brock so far are represented by a legal team that includes Anthony T. DiPietro, who has also represented patients of convicted sex offender and former Columbia University gynecologist Robert Hadden, and Mike Arias, who like DiPietro has represented patients of former USC gynecologist George Tyndall.

Brock, they allege, “has only recently ‘retired’ so that Cedars-Sinai can continue trying to conceal from plaintiffs, and the public at large, that Brock is a known serial predator, who has sexually exploited and abused hundreds, if not thousands, of unsuspecting female patients.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoOn a quest for global domination, Chinese EV makers are upending Thailand's auto industry

-

Health6 days ago

Health6 days agoNew Year life lessons from country star: 'Never forget where you came from'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24982514/Quest_3_dock.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24982514/Quest_3_dock.jpg) Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoMeta’s ‘software update issue’ has been breaking Quest headsets for weeks

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPassenger plane crashes in Kazakhstan: Emergencies ministry

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoIt's official: Biden signs new law, designates bald eagle as 'national bird'

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoThese are the top 7 issues facing the struggling restaurant industry in 2025

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Politics is bad for business.' Why Disney's Bob Iger is trying to avoid hot buttons

-

Culture3 days ago

Culture3 days agoThe 25 worst losses in college football history, including Baylor’s 2024 entry at Colorado