Science

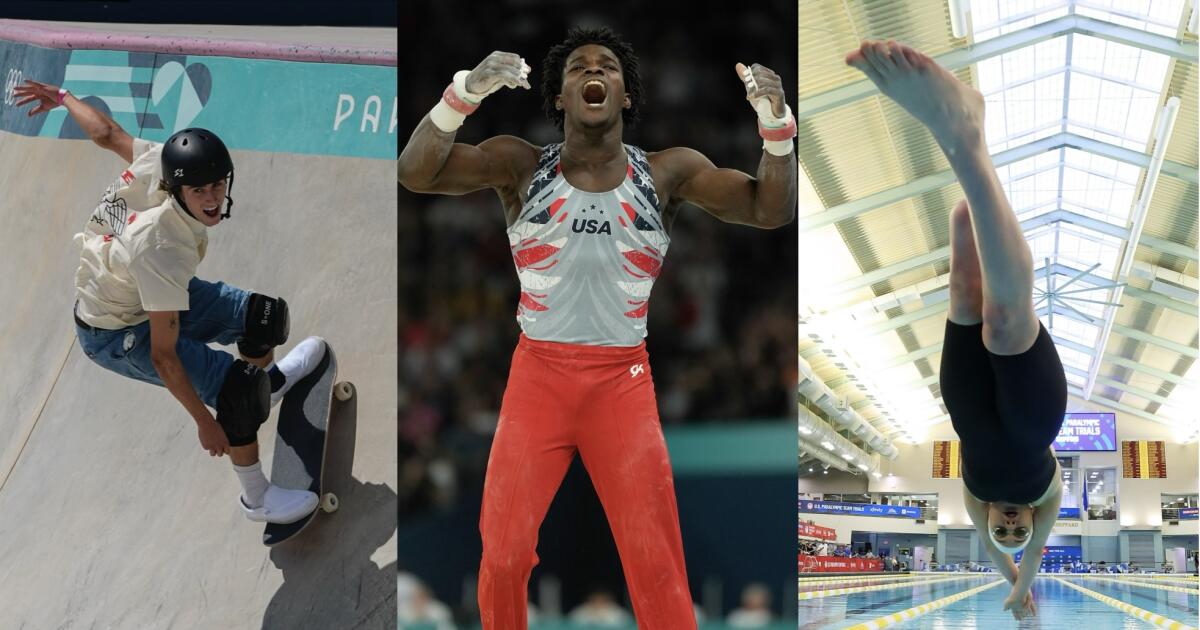

Q&A: Make the most of your workouts by training like the athletes of Team USA

The past two weeks of Olympic competition in Paris have brought us amazing stories of athletic skill, speed, triumph and redemption.

Perhaps they’ve left you newly inspired to train for a 10K or win your weekend basketball league.

Even if you’re not destined to compete on a world stage, learning how to fuel your body and mind like some of the country’s Olympic and Paralympic athletes may help you boost your own game.

Frederick Richard helped the U.S. men’s gymnastics team win a bronze medal, their first Olympic hardware in 16 years. San Diegan Tate Carew finished fifth in the men’s skateboard park final, and swimmer Ali Truwit — who lost part of her leg in a shark attack last year — will hit the pool in the coming weeks.

All three told The Times about the habits that earned them their spots on Team USA. Their comments have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How do you psych yourself up to work out on days when you just aren’t feeling it?

Frederick Richard: I have been in the gym since I was about 4 years old. I’m there because I love it but even so, there are days when I’m a little less inspired. On those days, I try to remember that it is the process that I enjoy and trust, which keeps me focused.

Ali Truwit: Knowing the deeper meaning of what I’m doing and why is my source of mental toughness on the days I’m not feeling like practicing. Right now, that larger purpose for me is turning trauma into hope and showing the world what people with disabilities are capable of. It drives me forward, even when I’m feeling sad or exhausted or in pain.

Is it OK to skip warming up or cooling down if you’re short on time?

Tate Carew: I rarely go into skating without stretching or warming up in some way. I’d rather have a shorter session knowing that I am preventing petty injuries.

FR: The warm-up and cool-down is not something to miss. You have to take care of your body.

What do you eat when you need a quick nutrition boost?

TC: A peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

FR: Celsius is my go-to drink when I need a little boost.

AT: I like to compete with a light stomach, so I like gluten-free pretzels or sometimes an apple. I love some mini Starbursts right before my race — a little sugar kick.

Do you have any tips about how to space out your meals and snacks?

FR: I definitely try not to eat too close to when I am going to bed.

TC: When I’m hungry, there is no such thing as a bad time to eat.

Any tips for staying properly hydrated? If you get sick of drinking water, is there anything you substitute instead?

AT: I carry a water bottle everywhere, all the time and try to just always be drinking. I also love Gatorade Zero!

TC: Watermelon has been a great substitute for me if I don’t feel like drinking water.

How do you get over jet lag when you travel for competitions?

FR: We generally try to get to places a day or two prior to the competition so that we can adjust to the time and the surroundings. For the Olympics we got to France about a week in advance.

AT: The way to handle conditions that aren’t ideal is to have handled them many times before in your practices. Then you know and believe you can do well anyway.

If you have trouble falling asleep the night before a high-stakes competition, what do you do?

AT: I’ve learned to put habits in place — like warm showers, relaxing mantras and funny shows — that take my mind to a more peaceful place.

FR: I try not to get too stressed, which I can do if I keep the big picture in mind. Trusting in the process is the key for me. I did bring my own mattress to Paris though!

Are there any mindfulness or meditation exercises that you find helpful?

TC: Whenever my mind feels extremely cluttered, I ask myself, “What problem do I have at this very moment?” Meaning, even if you are dealing with a lot in your home life, relationships, work, etc., what problems are you dealing with at that very moment?

AT: I love calm.com and Tamara Levitt! She has a very soothing voice, helpful big-picture insights, and breathwork. I also use progressive muscle relaxation as I’m trying to fall asleep, and I think that encourages the mind and body to let go.

How do you filter out distractions when it’s time to compete?

TC: I made my goals this year so clear that nothing would get in the way of me succeeding.

AT: I remind myself that work works and I’ve done the work. That helps a lot. One of the many reasons I train so hard is so that I can say that to myself before races.

I also just love racing so when I’m in a race, it’s often the only time of day for me that my mind is totally clear and focused.

If you make a mistake in the middle of a competition, how do you move forward instead of dwelling on it?

FR: I know that gymnastics is a judged sport so perfection is difficult. I also know that everyone is going to have some mistakes.

TC: Everything happens for a reason. In a way, it’s motivating for me.

Are there any other tips you’d like to share?

AT: Focus on what you love about competing — the people, the places, the habits you’ve ingrained in yourself, the joys of the process — and the rewards will be there no matter what.

These comments have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Science

California’s last nuclear plant clears major hurdle to power on

California environmental regulators on Thursday struck a landmark deal with Pacific Gas & Electric to extend the life of the state’s last remaining nuclear power plant in exchange for thousands of acres of new land conservation in San Luis Obispo County.

PG&E’s agreement with the California Coastal Commission is a key hurdle for the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant to remain online until at least 2030. The plant was slated to close this year, largely due to concerns over seismic safety, but state officials pushed to delay it — saying the plant remains essential for the reliable operation of California’s electrical grid. Diablo Canyon provides nearly 9% of the electricity generated in the state, making it the state’s single largest source.

The Coastal Commission voted 9-3 to approve the plan, settling the fate of some 12,000 acres that surround the power plant as a means of compensation for environmental harm caused by its continued operation.

Nuclear power does not emit greenhouse gases. But Diablo Canyon uses an estimated 2.5 billion gallons of ocean water each day to absorb heat in a process known as “once-through cooling,” which kills an estimated two billion or more marine organisms each year.

Some stakeholders in the region celebrated the conservation deal, while others were disappointed by the decision to trade land for marine impacts — including a Native tribe that had hoped the land would be returned to them. Diablo Canyon sits along one of the most rugged and ecologically rich stretches of the California coast.

Under the agreement, PG&E will immediately transfer a 4,500-acre parcel on the north side of the property known as the “North Ranch” into a conservation easement and pursue transfer of its ownership to a public agency such as the California Department of Parks and Recreation, a nonprofit land conservation organization or tribe. A purchase by State Parks would result in a more than 50% expansion of the existing Montaña de Oro State Park.

PG&E will also offer a 2,200-acre parcel on the southern part of the property known as “Wild Cherry Canyon” for purchase by a government agency, nonprofit land conservation organization or tribe. In addition, the utility will provide $10 million to plan and manage roughly 25 miles of new public access trails across the entire property.

“It’s going to be something that changes lives on the Central Coast in perpetuity,” Commissioner Christopher Lopez said at the meeting. “This matters to generations that have yet to exist on this planet … this is going to be a place that so many people mark in their minds as a place that transforms their lives as they visit and recreate and love it in a way most of us can’t even imagine today.”

Critically, the plan could see Diablo Canyon remain operational much longer than the five years dictated by Thursday’s agreement. While the state Legislature only authorized the plant to operate through 2030, PG&E’s federal license renewal would cover 20 years of operations, potentially keeping it online until 2045.

Should that happen, the utility would need to make additional land concessions, including expanding an existing conservation area on the southern part of the property known as the “South Ranch” to 2,500 acres. The plan also includes rights of first refusal for a government agency or a land conservation group to purchase the entirety of the South Ranch, 5,000 acres, along with Wild Cherry Canyon — after 2030.

Pelicans along the concrete breakwater at Pacific Gas and Electric’s Diablo Canyon Power Plant

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

Many stakeholders were frustrated by the carve-out for the South Ranch, but still saw the agreement as an overall victory for Californians.

“It is a once in a lifetime opportunity,” Sen. John Laird (D-Santa Cruz) said in a phone call ahead of Thursday’s vote. “I have not been out there where it has not been breathtakingly beautiful, where it is not this incredible, unique location, where you’re not seeing, for much of it, a human structure anywhere. It is just one of those last unique opportunities to protect very special land near the California coast.”

Others, however, described the deal as disappointing and inadequate.

That includes many of the region’s Native Americans who said they felt sidelined by the agreement. The deal does not preclude tribal groups from purchasing the land in the future, but it doesn’t guarantee that or give them priority.

The yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe of San Luis Obispo County and Region, which met with the Coastal Commission several times in the lead-up to Thursday’s vote, had hoped to see the land returned to them.

Scott Lanthrop is a member of the tribe’s board and has worked on the issue for several years.

“The sad part is our group is not being recognized as the ultimate conservationist,” he told The Times. “Any normal person, if you ask the question, would you rather have a tribal group that is totally connected to earth and wind and water, or would you like to have some state agency or gigantic NGO manage this land, I think the answer would be, ‘Hey, you probably should give it back to the tribe.’”

Tribe chair Mona Tucker said she fears that free public access to the land could end up harming it instead of helping it, as the Coastal Commission intends.

“In my mind, I’m not understanding how taking the land … is mitigation for marine life,” Tucker said. “It doesn’t change anything as far as impacts to the water. It changes a lot as far as impacts to the land.”

Montaña de Oro State Park.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

The deal has been complicated by jurisdictional questions, including who can determine what happens to the land. While PG&E owns the North Ranch parcel that could be transferred to State Parks, the South Ranch and Wild Cherry Canyon are owned by its subsidiary, Eureka Energy Company.

What’s more, the California Public Utilities Commission, which regulates utilities such as PG&E, has a Tribal Land Transfer Policy that calls for investor-owned power companies to transfer land they no longer want to Native American tribes.

In the case of Diablo Canyon, the Coastal Commission became the decision maker because it has the job of compensating for environmental harm from the facility’s continued operation. Since the commission determined Diablo’s use of ocean water can’t be avoided, it looked at land conservation as the next best method.

This “out-of-kind” trade-off is a rare, but not unheard of way of making up for the loss of marine life. It’s an approach that is “feasible and more likely to succeed” than several other methods considered, according to the commission’s staff report.

“This plan supports the continued operation of a major source of reliable electricity for California, and is in alignment with our state’s clean energy goals and focus on coastal protection,” Paula Gerfen, Diablo Canyon’s senior vice president and chief nuclear officer, said in a statement.

But Assemblymember Dawn Addis (D-Morro Bay) said the deal was “not the best we can do” — particularly because the fate of the South Ranch now depends on the plant staying in operation beyond 2030.

“I believe the time really is now for the immediate full conservation of the 12,000 [acres], and to bring accountability and trust back for the voters of San Luis Obispo County,” Addis said during the meeting.

There are also concerns about the safety of continuing to operate a nuclear plant in California, with its radioactive waste stored in concrete casks on the site. Diablo Canyon is subject to ground shaking and earthquake hazards, including from the nearby Hosgri Fault and the Shorline Fault, about 2.5 miles and 1 mile from the facility, respectively.

PG&E says the plant has been built to withstand hazards. It completed a seismic hazard assessment in 2024, and determined Diablo Canyon is safe to continue operation through 2030. The Coastal Commission, however, found if the plant operates longer, it would warrant further seismic study.

A key development for continuing Diablo Canyon’s operation came in 2022 with Senate Bill 846, which delayed closure by up to five additional years. At the time, California was plagued by rolling blackouts driven extreme heat waves, and state officials were growing wary about taking such a major source of power offline.

But California has made great gains in the last several years — including massive investments in solar energy and battery storage — and some questioned whether the facility is still needed at all.

Others said conserving thousands of acres of land still won’t make up for the harms to the ocean.

“It is unmitigatable,” said David Weisman, executive director of the nonprofit Alliance for Nuclear Responsibility. He noted that the Coastal Commission’s staff report says it would take about 99 years to balance the loss of marine life with the benefits provided by 4,500 acres of land conservation. Twenty more years of operation would take about 305 years to strike that same balance.

But some pointed out that neither the commission nor fisheries data find Diablo’s operations cause declines in marine life. Ocean harm may be overestimated, said Seaver Wang, an oceanographer and the climate and energy director at the Breakthrough Institute, a Berkeley-based research center.

In California’s push to transition to clean energy, every option comes with downsides, Wang said. In the case of nuclear power — which produces no greenhouse gas emissions — it’s all part of the trade off, he said.

“There’s no such thing as impacts-free energy,” he said.

The Coastal Commission’s vote is one of the last remaining obstacles to keeping the plant online. PG&E will also need a final nod from the Regional Water Quality Control Board, which decides on a pollution discharge permit in February.

The federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission will also have to sign off on Diablo’s extension.

Science

In search for autism’s causes, look at genes, not vaccines, researchers say

Earlier this year, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. pledged that the search for autism’s cause — a question that has kept researchers busy for the better part of six decades — would be over in just five months.

“By September, we will know what has caused the autism epidemic, and we’ll be able to eliminate those exposures,” Kennedy told President Trump during a Cabinet meeting in April.

That ambitious deadline has come and gone. But researchers and advocates say that Kennedy’s continued fixation on autism’s origins — and his frequent, inaccurate claims that childhood vaccines are somehow involved — is built on fundamental misunderstandings of the complex neurodevelopmental condition.

Even after more than half a century of research, no one yet knows exactly why some people have autistic traits and others do not, or why autism spectrum disorder looks so different across the people who have it. But a few key themes have emerged.

Researchers believe that autism is most likely the result of a complex set of interactions between genes and the environment that unfold while a child is in the womb. It can be passed down through families, or originate with a spontaneous gene mutation.

Environmental influences may indeed play a role in some autism cases, but their effect is heavily influenced by a person’s genes. There is no evidence for a single trigger that causes autism, and certainly not one a child encounters after birth: not a vaccine, a parenting style or a post-circumcision Tylenol.

“The real reason why it’s complicated, the more fundamental one, is that there’s not a single cause,” said Irva Hertz-Picciotto, a professor of public health science and director of the Environmental Health Sciences Center at UC Davis. “It’s not a single cause from one person to the next, and not a single cause within any one person.”

Kennedy, an attorney who has no medical or scientific training, has called research into autism’s genetics a “dead end.” Autism researchers counter that it’s the only logical place to start.

“If we know nothing else, we know that autism is primarily genetic,” said Joe Buxbaum, a molecular neuroscientist who directs the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “And you don’t have to actually have the exact genes [identified] to know that something is genetic.”

Some neurodevelopment disorders arise from a difference in a single gene or chromosome. People with Down syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21, for example, and Fragile X syndrome results when the FMR1 gene isn’t expressed.

Autism in most cases is polygenetic, which means that multiple genes are involved, with each contributing a little bit to the overall picture.

Researchers have found hundreds of genes that could be associated with autism; there may be many more among the roughly 20,000 in the human genome.

In the meantime, the strongest evidence that autism is genetic comes from studies of twins and other sibling groups, Buxbaum and other researchers said.

The rate of autism in the U.S. general population is about 2.8%, according to a study published last year in the journal Pediatrics. Among children with at least one autistic sibling, it’s 20.2% — about seven times higher than the general population, the study found.

Twin studies reinforce the point. Both identical and fraternal twins develop in the same womb and are usually raised in similar circumstances in the same household. The difference is genetic: identical twins share 100% of their genetic information, while fraternal twins share about 50% (the same as nontwin siblings).

If one fraternal twin is autistic, the chance that the other twin is also autistic is about 20%, or about the same as it would be for a nontwin sibling.

But if one in a pair of identical twins is autistic, the chance that the other twin is also autistic is significantly higher. Studies have pegged the identical twin concurrence rate anywhere from 60% to 90%, though the intensity of the twins’ autistic traits may differ significantly.

Molecular genetic studies, which look at the genetic information shared between siblings and other blood relatives, have found similar rates of genetic influence on autism, said Dr. John Constantino, a professor of pediatrics, psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Emory University School of Medicine and chief of behavioral and mental health at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Together, he said, “those studies have indicated that a vast share of the causation of autism can be traced to the effects of genetic influences. That is a fact.”

Buxbaum compares the heritability of autism to the heritability of height, another polygenic trait.

“There’s not one gene that’s making you taller or shorter,” Buxbaum said. Hundreds of genes play a role in where you land on the height distribution curve. A lot of those genes run in families — it’s not unusual for very tall people, for example, to have very tall relatives.

But parents pass on a random mix of their genes to their children, and height distribution across a group of same-sex siblings can vary widely. Genetic mutations can change the picture. Marfan syndrome, a condition caused by mutations in the FBN1 gene, typically makes people grow taller than average. Hundreds of genetic mutations are associated with dwarfism, which causes shorter stature.

Then once a child is born, external factors such as malnutrition or disease can affect the likelihood that they reach their full height potential.

So genes are important. But the environment — which in developmental science means pretty much anything that isn’t genetics, including parental age, nutrition, air pollution and viruses — can play a major role in how those genes are expressed.

“Genetics does not operate in a vacuum, and at the same time, the impact of the environment on people is going to depend on a person’s individual genetics,” said Brian K. Lee, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University who studies the genetics of developmental disorders.

Unlike the childhood circumstances that can affect height, the environmental exposures associated with autism for the most part take place in utero.

Researchers have identified multiple factors linked to increased risks of the disorder, including older parental age, infant prematurity and parental exposure to air pollution and industrial solvents.

Investigations into some of these linkages were among the more than 50 autism-related studies whose funding Kennedy has cut since taking office, a ProPublica investigation found. In contrast, no credible study has found links between vaccines and autism — and there have been many.

One move from the Department of Health and Human Services has been met with cautious optimism: even as Kennedy slashed funding to other research projects, the department in September announced a $50-million initiative to explore the interactions of genes and environmental factors in autism, which has been divided among 13 different research groups at U.S. universities, including UCLA and UC San Diego.

The department’s selection of well-established, legitimate research teams was met with relief by many autism scientists.

But many say they fear that such decisions will be an anomaly under Kennedy, who has repeatedly rejected facts that don’t conform to his preferred hypotheses, elevated shoddy science and muddied public health messaging on autism with inaccurate information.

Disagreements are an essential part of scientific inquiry. But the productive ones take place in a universe of shared facts and build on established evidence.

And when determining how to spend limited resources, researchers say, making evidence-based decisions is vital.

“There are two aspects of these decisions: Is it a reasonable expenditure based on what we already know? And if you spend money here, will you be taking money away from HHS that people are in desperate need of?” Constantino said. “If you’re going to be spending money, you want to do that in a way that is not discarding what we already know.”

Science

Contributor: New mothers are tempted by Ozempic but don’t have the data they need

My friend Sara, eight weeks after giving birth, left me a tearful voicemail. I’m a clinical psychologist specializing in postpartum depression and psychosis, but mental health wasn’t Sara’s issue. Postpartum weight gain was.

Sara told me she needed help. She’d gained 40 pounds during her pregnancy, and she was still 25 pounds overweight. “I’m going back to work and I can’t look like this,” she said. “I need to take Ozempic or something. But do you know if it’s safe?”

Great question. Unfortunately researchers don’t yet have an answer. On Dec. 1, the World Health Organization released its first guidelines on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists such as Ozempic, generically known as semaglutide. One of the notable policy suggestions in that report is to not prescribe GLP-1s to pregnant women. Disappointingly, the report says nothing about the use of the drug by postpartum women, including those who are breastfeeding.

There was a recent Danish study that led to medical guidelines against prescribing to patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

None of that is what my friend wanted to hear. I could only encourage her to speak to her own medical doctor.

Sara’s not alone. I’ve seen a trend emerging in my practice in which women use GLP-1s to shed postpartum weight. The warp speed “bounce-back” ideal of body shapes for new mothers has reemerged, despite the mental health field’s advocacy to abolish the archaic pressure of martyrdom in motherhood. GLP-1s are being sold and distributed by compound pharmacies like candy. And judging by their popularity, nothing tastes sweeter than skinny feels.

New motherhood can be a stressful time for bodies and minds, but nature has also set us up for incredible growth at that moment. Contrary to the myth of spaced-out “mommy brains,” new neuroplasticity research shows that maternal brains are rewired for immense creativity and problem solving.

How could GLP-1s affect that dynamic? We just don’t know. We do know that these drugs are associated with changes far beyond weight loss, potentially including psychiatric effects such as combating addiction.

Aside from physical effects, this points to an important unanswered research question: What effects, if any, do GLP-1s have on a woman’s brain as it is rewiring to attune to and take care of a newborn? And on a breastfeeding infant? If GLP-1s work on the pleasure center of the brain and your brain is rewiring to feel immense pleasure from a baby coo, I can’t help but wonder if that will be dampened. When a new mom wants a prescription for a GLP-1 to help shed baby weight, her medical provider should emphasize those unknowns.

These drugs may someday be a useful tool for new mothers. GLP-1s are helping many people with conditions other than obesity. A colleague of mine was born with high blood pressure and cholesterol. She exercised every day and adopted a pescatarian diet. Nothing budged until she added a GLP-1 to her regimen, bringing her blood pressure to a healthy 120/80 and getting cholesterol under control. My brother, an otherwise healthy young man recently diagnosed with a rare idiopathic lymphedema of his left leg, is considering GLP-1s to address inflammation and could be given another chance at improving his quality of life.

I hope that GLP-1s will continue to help those who need it. And I urge everyone — especially new moms — to proceed with caution. A healthy appetite for nutritious food is natural. That food fuels us for walks with our dogs, swims along a coastline, climbs through leafy woods. It models health and balance for the young ones who are watching us for clues about how to live a healthy life.

Nicole Amoyal Pensak, a clinical psychologist and researcher, is the author of “Rattled: How to Calm New Mom Anxiety With the Power of the Postpartum Brain.”

-

Alaska6 days ago

Alaska6 days agoHowling Mat-Su winds leave thousands without power

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump rips Somali community as federal agents reportedly eye Minnesota enforcement sweep

-

Ohio1 week ago

Who do the Ohio State Buckeyes hire as the next offensive coordinator?

-

Texas6 days ago

Texas6 days agoTexas Tech football vs BYU live updates, start time, TV channel for Big 12 title

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump threatens strikes on any country he claims makes drugs for US

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHonduras election council member accuses colleague of ‘intimidation’

-

Washington3 days ago

Washington3 days agoLIVE UPDATES: Mudslide, road closures across Western Washington

-

Iowa5 days ago

Iowa5 days agoMatt Campbell reportedly bringing longtime Iowa State staffer to Penn State as 1st hire