Science

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Some individuals argue that the identify is racist and disparages a whole continent. Others view it as offensive to homosexual males. After which there are those that concern it may result in indiscriminate killing of monkeys, as occurred in Brazil.

All that menace from one phrase: monkeypox.

Because the risk from the illness spreads, consultants around the globe have pledged to alter its identify to one thing that doesn’t carry the burden of stigma. No much less an authority than the World Well being Group is holding an open discussion board to elicit recommendations for a brand new moniker.

“Monkeypox is type of an odd identify to provide to a illness that’s now afflicting people,” mentioned Dr. Anthony Fauci, the U.S. authorities’s main skilled on infectious ailments.

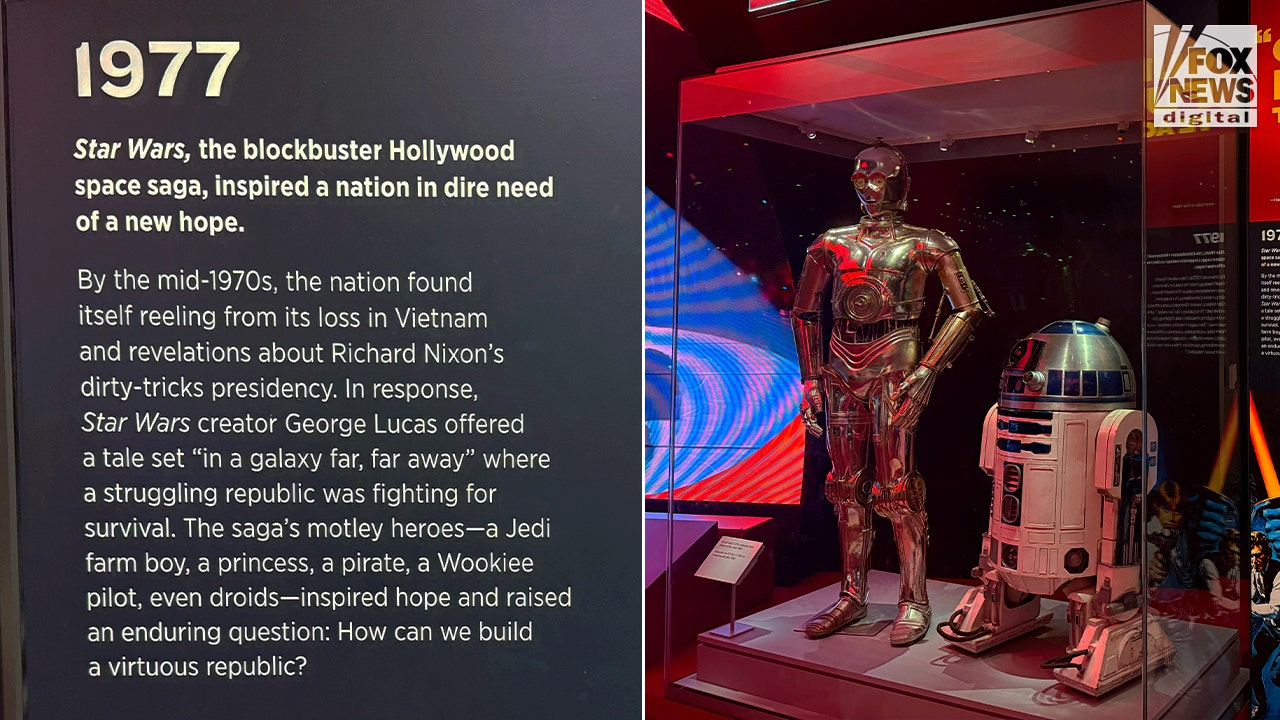

Individuals line up for the monkeypox vaccine at St. John’s Effectively Youngster & Household Heart in Los Angeles.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Occasions)

However tossing out the outdated identify is simpler than deciding on a brand new one.

Already, public well being companies, researchers and nonprofit organizations around the globe have taken it upon themselves to abbreviate or shorten the controversial identify. However at this level there’s little settlement on what to name the illness that has sickened greater than 46,700 individuals around the globe.

The California Division of Public Well being is referring to it as MPX — pronounced “M-P-X” or “em-pox” — because it waits for the WHO to choose a brand new identify. Officers in Oregon, Vermont, New Jersey and elsewhere have gone with hMPXV. Some LGBTQ neighborhood organizations in Canada use Mpox.

Altering the identify of an infectious illness in the midst of a rising outbreak could appear dangerous. However consultants are assured it may be finished — and that it could be riskier to do nothing. They concern the present identify may discourage sufferers from looking for therapy, trigger individuals to shun those that are contaminated, and reinforce racist tropes.

“Is there going to be one answer that’s going to make each single particular person glad? Nope,” mentioned Dr. Perry N. Halkitis, an infectious-disease epidemiologist and dean of the Rutgers College of Public Well being. “However there’s going to be one answer that’s going to be the least offensive of the entire options, and it’s going to maneuver us in a barely higher route with this illness.”

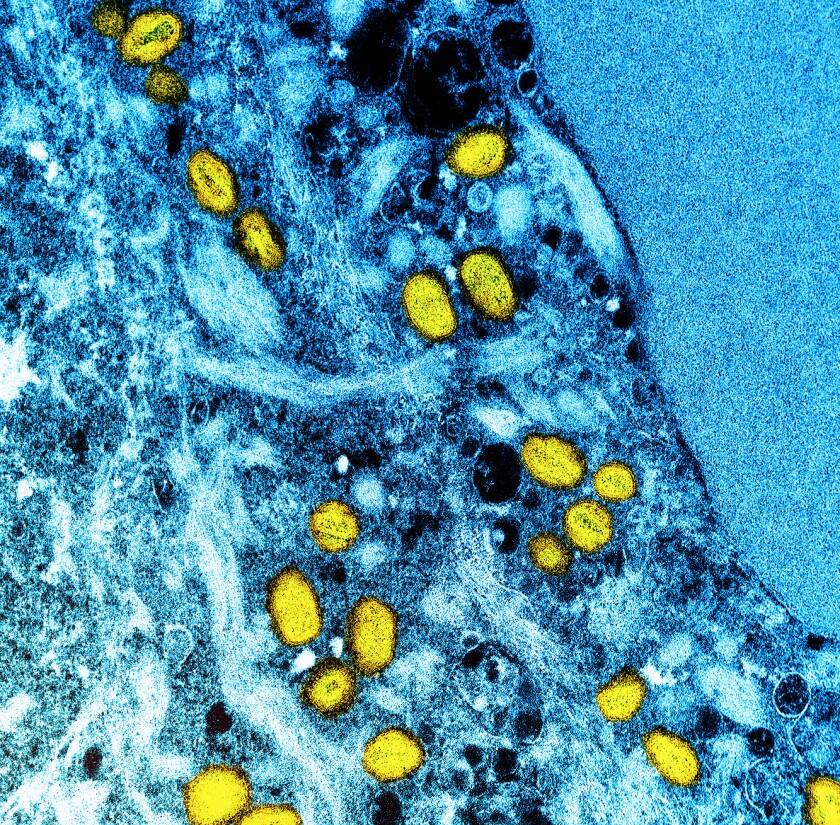

A electron micrograph photograph exhibits monkeypox particles, in yellow, infecting a cell.

(Nationwide Institute of Allergy and Infectious Ailments)

The identify dates again to 1958, when the virus was first documented in a bunch of lab monkeys in a Copenhagen analysis institute. It’s an orthopoxvirus, a sort that’s typically named for the animals by which they’re initially recognized. Its unique supply within the wild stays unknown, although it’s far more widespread in rodents than in primates.

Monkeypox was first recorded in people in 1970, in a 9-month-old boy within the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In previous outbreaks animals — particularly rodents — have been the first supply of transmission to people.

The illness is endemic in rural elements of western and central Africa, the place a number of thousand circumstances and scores of deaths are seen annually in women and men of all ages. Till not too long ago, the virus was hardly ever recognized to unfold from individual to individual. However within the present outbreak in Europe and North America, the overwhelming majority of circumstances have concerned transmission amongst males who’ve intercourse with males.

The situation — characterised by a rash and lesions that may appear to be pimples, bumps or blisters — can unfold by means of extended skin-to-skin contact with these lesions, which can be in hard-to-see locations or mistaken for different pores and skin points.

A cousin of smallpox, it acquired its identify greater than a half a century earlier than the WHO, the World Group for Animal Well being and the Meals and Agriculture Group of the United Nations set greatest practices for labeling ailments in 2015. Two of the no-no’s? Names that consult with international locations or geographical areas, and names tied to animals.

Phrases akin to “swine flu” and “Center East Respiratory Syndrome” have had “unintended unfavourable impacts by stigmatizing sure communities or financial sectors,” Dr. Keiji Fukuda, a former assistant director-general for well being safety on the WHO, mentioned in 2015.

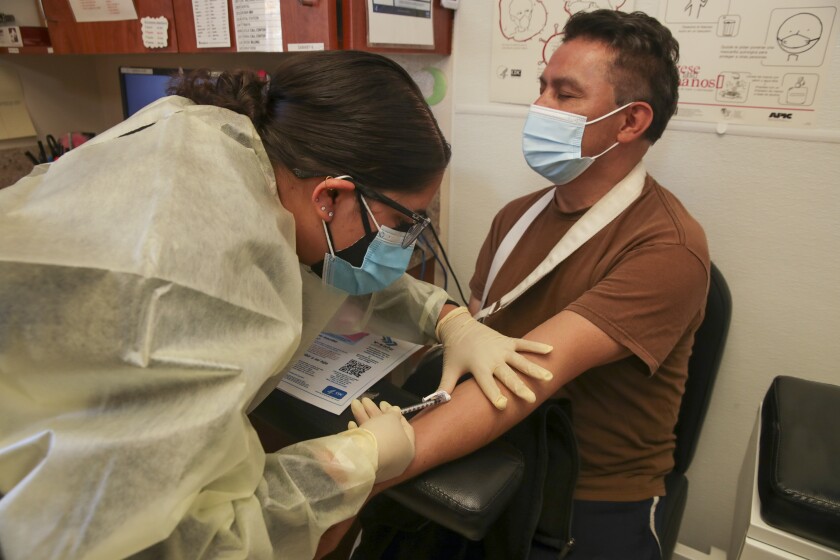

A medical employee offers a dose of the monkeypox vaccine at St. John’s Effectively Youngster & Household Heart in Los Angeles.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Occasions)

“We’ve seen sure illness names provoke a backlash towards members of specific spiritual or ethnic communities, create unjustified limitations to journey, commerce and commerce, and set off useless slaughtering of meals animals,” he mentioned. “This could have severe penalties for peoples’ lives and livelihoods.”

Considerations like these had been voiced in June about the truth that the 2 main teams of the monkeypox virus had been generally known as the Congo Basin clade and the West African clade. A global group of scientists referred to as for these labels to be dropped on the grounds that linking the illness to Africa “is just not solely inaccurate however can be discriminatory and stigmatizing.”

Christian Happi, who helped put the marketing campaign in movement, took problem with media retailers’ use of historic photographs of African sufferers for example an outbreak in the UK and North America, calling it, “nothing else however racism to the core.”

The WHO agreed with the scientists. This month, it introduced that the Congo Basin clade will now be generally known as Clade one or I, and the West African clade can be generally known as Clade two or II.

“This was a giant victory,” mentioned Happi, the founder and director of the African Heart of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Ailments in Redeemer’s College, Ede, Nigeria. “We in Africa will now not settle for to be undermined. We’ll stand as much as something that’s towards the picture of this continent or that tries to undermine the picture of this continent.”

Medical assistant Susana Alvarenga offers a dose of the monkeypox vaccine Aug. 10 at St. John’s Effectively Youngster & Household Heart.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Occasions)

Ask individuals what they dislike in regards to the identify “monkeypox” and also you’ll probably get a special reply from every of them.

For Halkitis, it’s that it displays “a historical past of nomenclature associated to ailments that assigns blame.” He cited the early days of the AIDS epidemic, when the illness was mislabeled as “gay-related immune deficiency” or “GRID.”

“Utilizing the phrase ‘monkey’ to consult with a virus not solely immediately hyperlinks it to an animal that’s related to the African continent, but in addition associates doubtlessly the habits of homosexual males as ‘monkey-like,’” Halkitis mentioned. “Within the palms of the fallacious individuals” that may stigmatize those that is likely to be affected by the illness, he added.

Halkitis isn’t involved that altering the virus’ identify mid-outbreak will sow confusion, however he did acknowledge that developing with one thing new gained’t be simple.

In a current seminar at Rutgers, he referred to the illness as “MPX,” an alternate he referred to as “completely not splendid” after studying that MPX was the identify for a sort of submachine gun. He referred to as “Mpox” a potential possibility, however not a fantastic one as a result of “the monkey attribution doesn’t actually go away.”

Individuals verify in to get a monkeypox vaccination Aug. 9 at a walk-up web site at Barnsdall Artwork Park in Hollywood.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Occasions)

“I feel there’s some actually sensible individuals on the market who work in advertising who can consider a great identify,” he mentioned.

Dr. Richard Besser, president and CEO of the Robert Wooden Johnson Basis, mentioned the present identify creates a false and disparaging affiliation between monkeys and individuals who catch the illness, which may create limitations for these looking for care.

Besser was appearing director of the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention through the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009. That illness was generally known as “swine flu,” a apply that “created false associations of people that acquired the flu with having had contact with pigs.” (The pork trade took a significant hit as effectively, he mentioned.)

“There all the time are challenges in altering a reputation of a illness within the midst of an outbreak, however that shouldn’t be a barrier to altering the identify if the identify in and of itself is inflicting hurt,” Besser mentioned. Certainly, he mentioned, the scientific neighborhood ought to have a look at “a wholesale rebranding of numerous ailments.”

“There are numerous viruses which have been named after totally different locations in Africa, which contributes to an inappropriate affiliation of illness and pestilence to elements of Africa,” Besser mentioned.

Kathleen Corridor Jamieson, director of the College of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Coverage Heart and an skilled on science communication, takes problem with the truth that the identify monkeypox “doesn’t convey helpful data.”

The “pox” half is okay as a result of the general public is acquainted with that phrase, she mentioned. However the “monkey” half would “counsel it infects monkeys.”

She mentioned the general public will simply adapt to a brand new identify as soon as there’s a consensus about what that must be.

“You’d wish to have finished it earlier than the outbreak,” she mentioned. However, “individuals will shortly neglect what you used to name it.”

The ultimate phrase on a brand new identify rests with the keepers of the Worldwide Classification of Ailments, a complete catalog of well being problems maintained by the WHO.

The renaming course of is anticipated to take quite a few months, in response to the company. The WHO will replace the general public by the top of the 12 months.

“I’m positive we is not going to give you a ridiculous identify,” mentioned WHO spokesperson Fadela Chaib.

Feedback left on proposals posted on a WHO web site illustrate why discovering a brand new identify gained’t be simple.

To somebody suggesting “Magnuspox”: “Illness names ought to ideally not use individuals’s correct names. There are individuals referred to as Magnus, and so they shouldn’t have their names related to this illness.”

To a different proposing “Pox22″: “Monkeypox was first found in people in 1970, so Pox70 would match higher in the event you wished to call it like COVID-19.”

And concerning “tinypox”: “monkeypox lesions are even greater than smallpox ones, so tiny is out of the query.”

RÉZO Santé, a Montreal-based nonprofit that gives well being providers to the queer neighborhood, submitted a proposal to undertake “Mpox,” a reputation generated by an alliance of Canadian LGBTQ organizations.

“There have been individuals who instantly noticed that monkeypox in its present type had a little bit of a stigmatizing look and it was actually necessary for us to maneuver away from that as shortly as potential,” mentioned Samuel Miriello, the director of HR and Partnerships for the group. Mpox “is the simplest identify change to know.”

The group not too long ago related with Jean-Yves Duclos, the Canadian well being minister, to debate the brand new identify, however he frightened that making a change earlier than the WHO decides on a brand new identify may end in confusion, Miriello mentioned. (Duclos didn’t reply to a request for remark.)

There’s one other potential drawback with Mpox — it’s already the identify of a degenerative illness that afflicts mutants, together with X-Males akin to Rogue and Cyclops, within the Marvel universe.

Occasions workers author Marissa Evans contributed to this report.

Science

NIH budget cuts threaten the future of biomedical research — and the young scientists behind it

Over the last several months, a deep sense of unease has settled over laboratories across the United States. Researchers at every stage — from graduate students to senior faculty — have been forced to shelve experiments, rework career plans, and quietly warn each other not to count on long-term funding. Some are even considering leaving the country altogether.

This growing anxiety stems from an abrupt shift in how research is funded — and who, if anyone, will receive support moving forward. As grants are being frozen or rescinded with little warning and layoffs begin to ripple through institutions, scientists have been left to confront a troubling question: Is it still possible to build a future in U.S. science?

On May 2, the White House released its Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request, proposing a nearly $18-billion cut from the National Institutes of Health. This cut, which represents approximately 40% of the NIH’s 2025 budget, is set to take effect on Oct. 1 if adopted by Congress.

“This proposal will have long-term and short-term consequences,” said Stephen Jameson, president of the American Assn. of Immunologists. “Many ongoing research projects will have to stop, clinical trials will have to be halted, and there’ll be the knock-on effects on the trainees who are the next generation of leaders in biomedical research. So I think there’s going to be varied and potentially catastrophic effects, especially on the next generation of our researchers, which in turn will lead to a loss of the status of the U.S. as a leader in biomedical research.“

In the request, the administration justified the move as part of its broader commitment to “restoring accountability, public trust, and transparency at the NIH.” It accused the NIH of engaging in “wasteful spending” and “risky research,” releasing “misleading information,” and promoting “dangerous ideologies that undermine public health.”

National Institutes of Health.

(NIH.gov)

To track the scope of NIH funding cuts, a group of scientists and data analysts launched Grant Watch, an independent project that monitors grant cancellations at the NIH and the National Science Foundation. This database compiles information from public government records, official databases, and direct submissions from affected researchers, grant administrators, and program directors.

As of July 3, Grant Watch reports 4,473 affected NIH grants, totaling more than $10.1 billion in lost or at-risk funding. These include research and training grants, fellowships, infrastructure support, and career development awards — and affect large and small institutions across the country. Research grants were the most heavily affected, accounting for 2,834 of the listed grants, followed by fellowships (473), career development awards (374) and training grants (289).

The NIH plays a foundational role in U.S. research. Its grants support the work of more than 300,000 scientists, technicians and research personnel, across some 2,500 institutions and comprising the vast majority of the nation’s biomedical research workforce. As an example, one study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that funding from the NIH contributed to research associated with every one of the 210 new drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration between 2010 and 2016.

Jameson emphasized that these kinds of breakthroughs are made possible only by long-term federal investment in fundamental research. “It’s not just scientists sitting in ivory towers,” he said. “There are enough occasions where [basic research] produces something new and actionable — drugs that will save lives.”

That investment pays off in other ways too. In a 2025 analysis, United for Medical Research, a nonprofit coalition of academic research institutions, patient groups and members of the life sciences industry, found that every dollar the NIH spends generates $2.56 in economic activity.

A ‘brain drain’ on the horizon

Support from the NIH underpins not only research, but also the training pipeline for scientists, physicians and entrepreneurs — the workforce that fuels U.S. leadership in medicine, biotechnology and global health innovation. But continued American preeminence is not a given. Other countries are rapidly expanding their investments in science and research-intensive industries.

If current trends continue, the U.S. risks undergoing a severe “brain drain.” In a March survey conducted by Nature, 75% of U.S. scientists said they were considering looking for jobs abroad, most commonly in Europe and Canada.

This exodus would shrink domestic lab rosters, and could erode the collaborative power and downstream innovation that typically follows discovery. “It’s wonderful that scientists share everything as new discoveries come out,” Jameson said. “But, you tend to work with the people who are nearby. So if there’s a major discovery in another country, they will work with their pharmaceutical companies to develop it, not ours.”

At UCLA, Dr. Antoni Ribas has already started to see the ripple effects. “One of my senior scientists was on the job market,” Ribas said. “She had a couple of offers before the election, and those offers were higher than anything that she’s seen since. What’s being offered to people looking to start their own laboratories and independent research careers is going down — fast.”

In addition, Ribas, who directs the Tumor Immunology Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, says that academia and industry are now closing their door to young talent. “The cuts in academia will lead to less positions being offered,” Ribas explained. “Institutions are becoming more reluctant to attract new faculty and provide startup packages.” At the same time, he said, the biotech industry is also struggling. “Even companies that were doing well are facing difficulties raising enough money to keep going, so we’re losing even more potential positions for researchers that are finishing their training.”

This comes at a particularly bitter moment. Scientific capabilities are soaring, with new tools allowing researchers to examine single cells in precise detail, probe every gene in the genome, and even trace diseases at the molecular level. “It’s a pity,” Ribas said, “Because we have made demonstrable progress in treating cancer and other diseases. But now we’re seeing this artificial attack being imposed on the whole enterprise.”

Without federal support, he warns, the system begins to collapse. “It’s as if you have a football team, but then you don’t have a football field. We have the people and the ideas, but without the infrastructure — the labs, the funding, the institutional support — we can’t do the research.”

For graduate students and postdoctoral fellows in particular, funding uncertainty has placed them in a precarious position.

“I think everyone is in this constant state of uncertainty,” said Julia Falo, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Berkeley and recording secretary of UAW 4811, the union for workers at the University of California. “We don’t know if our own grants are going to be funded, if our supervisor’s grants are going to be funded, or even if there will be faculty jobs in the next two years.”

She described colleagues who have had funding delayed or withdrawn without warning, sometimes for containing flagged words like “diverse” or “trans-” or even for having any international component.

The stakes are especially high for researchers on visas. As Falo points out for those researchers, “If the grant that is funding your work doesn’t exist anymore, you can be issued a layoff. Depending on your visa, you may have only a few months to find a new job — or leave the country.”

A graduate student at a California university, who requested anonymity due to the potential impact on their own position — which is funded by an NIH grant— echoed those concerns. “I think we’re all a little on edge. We’re all nervous,” they said. “We have to make sure that we’re planning only a year in advance, just so that we can be sure that we’re confident of where that funding is going to come from. In case it all of a sudden gets cut.”

The student said their decision to pursue research was rooted in a desire to study rare diseases often overlooked by industry. After transitioning from a more clinical setting, they were drawn to academia for its ability to fund smaller, higher-impact projects — the kind that might never turn a profit but could still change lives. They hope to one day become a principal investigator, or PI, and lead their own research lab.

Now, that path feels increasingly uncertain. “If things continue the way that they have been,” they said. “I’m concerned about getting or continuing to get NIH funding, especially as a new PI.”

Still, they are staying committed to academic research. “If we all shy off and back down, the people who want this defunded win.”

Rallying behind science

Already, researchers, universities and advocacy groups have been pushing back against the proposed budget cut.

On campuses across the country, students and researchers have organized rallies, marches and letter-writing campaigns to defend federal research funding. “Stand Up for Science” protests have occurred nationwide, and unions like UAW 4811 have mobilized across the UC system to pressure lawmakers and demand support for at-risk researchers. Their efforts have helped prevent additional state-level cuts in California: in June, the Legislature rejected Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed $129.7-million reduction to the UC budget.

Earlier this year, a coalition of public health groups, researchers and unions — led by the American Public Health Assn. — sued the NIH and Department of Health and Human Services over the termination of more than a thousand grants. On June 16, U.S. District Judge William Young ruled in their favor, ordering the NIH to reinstate over 900 canceled grants and calling the terminations unlawful and discriminatory. Although the ruling applies only to grants named in the lawsuit, it marks the first major legal setback to the administration’s research funding rollback.

Though much of the current spotlight (including that lawsuit) has focused on biomedical science, the proposed NIH cuts threaten research far beyond immunology or cancer. Fields ranging from mental health to environmental science stand to lose crucial support. And although some grants may be in the process of reinstatement, the damage already done — paused projects, lost jobs and upended career paths — can’t simply be undone with next year’s budget.

And yet, amid the fear and frustration, there’s still resolve. “I’m floored by the fact that the trainees are still devoted,” Jameson said. “They still come in and work hard. They’re still hopeful about the future.”

Science

Should bioplastics be counted as compost? Debate pits farmers against manufacturers

Greg Pryor began composting yard and food waste for San Francisco in 1996, and today he oversees nine industrial-sized composting sites in California and Oregon that turn discarded banana peels, coffee grounds, chicken bones and more into a dark, nutrient-rich soil that farmers covet for their fields and crops.

His company, Recology, processes organic waste from cities and municipalities across the Bay Area, Central Valley, Northern California, Oregon and Washington — part of a growing movement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by minimizing food waste in landfills.

But, said Pryor, if bioplastic and compostable food packaging manufacturers’ get their way, the whole system could collapse.

At issue is a 2021 California law, known as Assembly Bill 1201, which requires that products labeled “compostable” must actually break down into compost, not contaminate soil or crops with toxic chemicals, and be readily identifiable to both consumers and solid waste facilities.

The law also stipulates that products carrying a “compostable” label must meet the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program requirements, which only allow for plant and animal material in compost feedstock, and bar all synthetic substances and materials — plastics, bioplastics and most packaging materials — except for newspaper or other recycled paper without glossy or colored ink.

Close-up of text on plastic cup reading Made From Corn, referring to plant derived bioplastics.

(Getty Images)

The USDA is reviewing those requirements at the request of a compostable plastics and packaging industry trade group. Its ruling, expected this fall, could open the door for materials such as bioplastic cups, coffee pods and compostable plastic bags to be admitted into the organic compost waste stream.

Amid pressure from the industry, the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery said it will await implementing its own rules on AB 1201 — originally set for Jan. 1, 2026 — until June 30, 2027, to incorporate the USDA guidelines, should there be a change.

Pryor is concerned that a USDA ruling to allow certain plastic to be considered compost will contaminate his product, make it unsaleable to farmers, and undermine the purpose of composting — which is to improve soil and crop health.

Plastics, microplastics and toxic chemicals can hurt and kill the microorganisms that make his compost healthy and valued. Research also shows these materials, chemicals and products can threaten the health of crops grown in them.

And while research on new generation plastics made from plant and other organic fibers have more mixed findings — suggesting some fibers, in some circumstances, may not be harmful — Pryor said the farmers who buy his compost don’t want any of it. They’ve told him they won’t buy it if he accepts it in his feedstock.

“If you ask farmers, hey, do you mind plastic in your compost? Every one of them will say no. Nobody wants it,” he said.

However, for manufacturers of next-generation, “compostable” food packaging products — such as bioplastic bags, cups and takeout containers made from corn, kelp or sugarcane fibers — those federal requirements present an existential threat to their industry.

That’s because California is moving toward a new waste management regime which, by 2032, will require all single-use plastic packaging products sold in the state to be either recyclable or compostable.

A worker at Recology’s Blossom Valley composting site rides his bike back to the sorting machines after a break in Vernalis, Calif., on June 26.

(Susanne Rust / Los Angeles Times)

If the products these companies have designed and manufactured for the sole purpose of being incorporated in the compost waste stream are excluded, they will be shut out of the huge California market.

They say their products are biodegradable, contain minimal amounts of toxic chemicals and metals, and provide an alternative to the conventional plastics used to make chip bags, coffee pods and frozen food trays — and wind up in landfills, rivers and oceans.

“As we move forward, not only are you capturing all this material … such as coffee grounds, but there isn’t really another packaging solution in terms of finding an end of life,” for these products, said Alex Truelove, senior policy manager for the Biodegradable Product Institute, a trade organization for compostable packaging producers.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Material is loaded into a mixing truck where biosolids and amendments are combined then stored in climate controlled piles to cure at the Tulare Lake Compost plant. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

“Even if you could recycle those little cups, which it seems like no one is willing to do … it still requires someone to separate out and peel off the foil top and dump out the grounds. Imagine if you could just have a really thin covering or really thin packaging, and then you could just put it all in” the compost he said. “How much more likely would it be for people to participate?”

Truelove and Rhodes Yepsen, the executive director of the bioplastic institute, also point to compost bin and can liners, noting that many people won’t participate in separating out their food waste if they can’t put it in a bag — the “yuck” factor. If you create a compostable bag, they say, more people will buy into the program.

The institute — whose board members include or have included representatives from the chemical giant BASF Corp., polystyrene manufacturer Dart Container, Eastman Chemical Co. and PepsiCo — is lobbying the federal and state government to get its products into the compost stream.

Greg Pryor, Recology’s director of landfill and organics, stands in front of a pile of processed compost at the integrated waste management’s Blossom Valley compost site in Vernalis, Calif., on June 26.

(Susanne Rust / Los Angeles Times)

The institute also works as a certifying body, testing, validating and then certifying compostable packaging for composting facilities across the U.S. and Canada.

In 2023, it petitioned the USDA to reconsider its exclusion of certain synthetic products, calling the current requirements outdated and “one of the biggest stumbling blocks” to efforts in states, such as California, that are trying to create a circular economy, in which products are designed and manufactured to be reused, recycled or composted.

In response, the federal agency contracted the nonprofit Organics Material Review Institute to compile a report evaluating the research that’s been conducted on these products’ safety and compostability.

The institute’s report, released in April, highlighted a variety of concerns including the products’ ability to fully biodegrade — potentially leaving microplastics in the soil — as well as their tendency to introduce forever chemicals, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and other toxic chemicals into the soil.

“Roughly half of all bioplastics produced are non-biodegradable,” the authors wrote. “To compensate for limitations inherent to bioplastic materials, such as brittleness and low gas barrier properties, bioplastics can contain additives such as synthetic polymers, fillers, and plasticizers. The specific types, amounts, and hazards of these chemicals in bioplastics are rarely disclosed.”

The report also notes that while some products may break down relatively efficiently in industrial composting facilities, when left out in the environment, they may not break down at all. What’s more, converting to biodegradable plastics entirely could result in an increase in biodegradable waste in landfills — and with it emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, the authors wrote.

Yepsen and Truelove say their organization won’t certify any products in which PFAS — a chemical often used to line cups and paper to keep out moisture — was intentionally added, or which is found in levels above a certain threshold. And they require 90% biodegradation of the products they certify.

Judith Enck, a former regional Environmental Protection Agency director, and the founder of Beyond Plastics, an anti-plastic waste environmental group based in Bennington, Vt., said the inclusion of compost as an end-life option for packaging in California’s new waste management regime was a mistake.

“What it did was to turn composting into a waste disposal strategy, not a soil health strategy,” she said. “The whole point of composting is to improve soil health. But I think what’s really driving this debate right now is consumer brand companies who just want the cheapest option to keep producing single-use packaging. And the chemical companies, because they want to keep selling chemicals for packaging and a lot of so-called biodegradable or compostable packaging contains those chemicals.”

Bob Shaffer, an agronomist and coffee farmer in Hawaii, said he’s been watching these products for years, and won’t put any of those materials in his compost.

“Farmers are growing our food, and we’re depending on them. And the soils they grow our crops in need care,” he said. “I’ll grow food for you, and I’ll grow gorgeous food for you, but give us back the food stuff you’re not using or eating, so we can compost it, return it to the soil, and make a beautiful crop for you. But be mindful of what you give back to us. We can’t grow you beautiful food from plastic and toxic chemicals.”

Recology’s Pryor said the food waste his company receives has increasingly become polluted with plastic.

He pointed toward a pile of food waste at his company’s composting site in the San Joaquin Valley town of Vernalis. The pile looked less like a heap of rotting and decaying food than a dirty mound of plastic bags, disposable coffee cups, empty, greasy chip bags and takeout boxes.

“I’ve been doing this for more than three decades, and I can tell you the food we process hasn’t changed over that time,” he said. “Neither have the leaves, brush and yard clippings we bring in. The only thing that’s changed? Plastics and biodegradable plastics.”

He said if the USDA and CalRecycle open the doors for these next-generation materials, the problem is just going to get worse.

“People are already confused about what they can and can’t put in,” he said. “Opening the door for this stuff is jut going to open the floodgates. For all kinds of materials. It’s a shame.”

Science

Federal contractors improperly dumped wildfire-related asbestos waste at L.A. area landfills

Federal contractors tasked with clearing ash and debris from the Eaton and Palisades wildfires improperly sent truckloads of asbestos-tainted waste to nonhazardous landfills, including one where workers were not wearing respiratory protection, according to state and local records.

From Feb. 28 to March 24, federal cleanup crews gathered up wreckage from six burned-down homes as part of the wildfire recovery efforts led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its primary contractor Environmental Chemical Corp.

However, prior to reviewing mandated tests for asbestos, crews loaded the fire debris onto dump trucks bound for Simi Valley Landfill and Recycling Center, and possibly Calabasas Landfill in unincorporated Agoura and Sunshine Canyon Landfill in Los Angeles’ Sylmar neighborhood, according to reports by the California Office of Emergency Services and Ventura County.

Later on, federal contractors learned those tests determined that the fire debris from these homes contained asbestos, a fire-resistant building material made up of durable thread-like fibers that can cause serious lung damage if inhaled.

The incident wasn’t reported to landfill operators or environmental regulators until weeks later in mid-April.

Many Southern California residents and environmental groups had already objected to sending wildfire ash and debris to local landfills that were not designed to handle high levels of contaminants and potentially hazardous waste that are often commingled in wildfire debris. They feared toxic substances — including lead and asbestos — could pose a risk to municipal landfill workers and might even drift into nearby communities as airborne dust.

The botched asbestos disposal amplifies those concerns and illustrates that in some cases federal contractors are failing to adhere to hazardous waste protocols.

“You have to wonder if they caught it here, how many times didn’t they catch it?” asked Jane Williams, executive director of the nonprofit California Communities Against Toxics. “It’s the continued failure to effectively protect the public from the ash. This is further evidence of that failure. This is us deciding those who work and live around these landfills are expendable.”

As of May 1, nearly 1 million tons of disaster debris has been taken to four landfills in Southern California. Simi Valley, an 887-acre landfill in Ventura County, has taken two-thirds of the tonnage. Several residents who live nearby voiced their disappointment ahead of the June 24 Ventura County Board of Supervisors vote to approve emergency waivers to allow fire debris to continue to be disposed of at Simi Valley Landfill — without a cap on tonnage — until Sept. 3.

“When I told my kids about the fire debris being dumped at the landfill, they asked me, why would anyone allow us to be exposed to this?” said Nicole Luekenga, a resident of nearby Moorpark, at the June 24 board meeting. “We are deeply concerned about the potential health risks from the fire debris being dumped at a residential landfill in our community. It feels as though profit and convenience are being prioritized over public safety, and that is unacceptable.”

An Environmental Chemical Corp. official acknowledged the lapse in asbestos protocols led to the improper disposal in February and March. He said the ash and debris from the six homes — four in Altadena, one in Pacific Palisades and one in Malibu — contained “trace amounts” of asbestos but did not elaborate on the specific type of building material that contained asbestos, or why the debris wasn’t flagged.

Asbestos has historically been used in a variety of construction materials — large and small — including roofing shingles, cement pipes, popcorn ceilings and insulation.

The company official said the improper disposal may have been due to a failure of either its workers or subcontractors to properly review paperwork. He also said he was unaware of any other cases in which asbestos or hazardous waste were improperly disposed. The Army Corps of Engineers declined to comment on the matter.

Environmental Chemical officials told Simi Valley Landfill that the asbestos should be presumed to be friable, a form of the fibrous mineral that is more easily broken down into smaller pieces and considered hazardous waste, according to an April letter from the landfill’s owner, Waste Management, to the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board.

During the time the asbestos waste was taken to the landfills, workers handling fire debris at Simi Valley Landfill had not been wearing protective masks or respirators, according to inspection reports. Typically municipal landfill workers don’t wear face coverings because they are mostly handling trash and nonhazardous waste.

But experts say protective masks are essential for protecting worker health at landfills. Landfill workers or hired contractors regularly drill pipelines extending hundreds of feet underground into the layers of the waste to extract gases that can build up when garbage decomposes. Experts say drilling into hazardous waste, such as asbestos waste, could expose workers to harmful substances if they aren’t wearing appropriate protective equipment.

During at least one visit in March, a Ventura County inspector found workers without masks in parts of the landfill designated for fire debris. Waste Management staff told the county inspector that mask-wearing was voluntary for employees. In April, county inspectors observed at least four workers constructing a new well in the fire debris area without respiratory protection, and another worker with only a cloth face mask.

High-filtration respirators are typically considered the best form of protection against asbestos. Protective masks, such as N95 masks, can guard against breathing in small particles, but should not be used to protect against asbestos.

Since learning about the asbestos-containing fire debris, local regulators have ordered the operators of Simi Valley Landfill to consult with safety professionals to determine the appropriate level of protective gear needed to protect against breathing in hazardous contaminants.

Army Corps officials had previously vowed that contractors would test for asbestos and take steps to segregate this waste and to take it to the appropriate disposal locations, such as Azusa Land Reclamation Co., a 300-acre landfill in the San Gabriel Valley that is also owned by Waste Management.

Waste Management officials said the company intends to leave the asbestos-containing waste in place, because attempting to excavate it could increase the likelihood that some of the toxic material would be released into the air. Nicole Stetson, district manager at Waste Management, urged the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Board to ask Environmental Chemical what actions it would take to prevent more asbestos from inadvertently being dumped there.

The landfill staff “followed all relevant procedures during affected period and could not have prevented these events through any reasonable means,” Stetson wrote in a letter in April.

So far, regulators have been mum on whether any enforcement action has been taken after the lapse in hazardous waste protocols. The regional water board declined to comment. CalRecycle referred questions to local authorities that it partners with to provide oversight and ensure compliance.

The Army Corps of Engineers is more than halfway through its mission of clearing the wildfire debris from the vast majority of homes and schools that were razed in the Eaton and Palisades wildfires. So far, it has overseen the removal of fire debris from nearly 9,000 properties.

The wildfire ash and debris the Army Corps has moved from disaster sites to landfills probably contains elevated levels of toxic metals. For example, Nick Spada, a researcher with the UC Davis Air Quality Research Center, has collected dozens of ash samples from the burn scars and, in preliminary findings, found elevated levels of lead, arsenic, cadmium and antimony in the test materials.

Spada is sampling the air near Simi Valley Landfill in hopes of identifying the levels of dust pollution from the site. The air sampling will help determine the types of metals in the air along with the particle sizes. (Smaller particles can cause more health complications because after they are inhaled into lungs, some are tiny enough to enter the bloodstream.)

Spada said the forthcoming results should provide communities with important greater insight into public health risks associated with the wildfire debris that continues to be dumped there. But, beyond the community, Spada is also concerned with those who are the closest to the debris: the workers.

“I see our role as raising concerns and then exploring them and trying to help out our friends in the regulatory agencies and the government that are all working as hard as they can trying to get a handle on this massive tragedy,” he said. “I’m concerned about all the workers who are in the burn areas, who are doing this work without respirators. It’s really hot, so heat-related illnesses is a primary concern, as is respiration of these particles.”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoHow Every Senator Voted on the Iran War Powers Resolution

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump's 'big, beautiful bill' faces Republican family feud as Senate reveals its final text

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoFacebook is starting to feed its Meta AI with private, unpublished photos

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoWhy Mariah Carey Doesn’t Use a Scale After Her 70-Lb Weight Loss

-

World1 week ago

Tech industry group sues Arkansas over new social media laws

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWhat is birthright citizenship and what happens after the Supreme Court ruling?

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoCalifornia lawmakers approve expanded $750-million film tax credit program

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoAfter U.S. and Israeli Strikes, Could Iran Make a Nuclear Bomb?