Science

Just off California, octopuses are converging by the thousands. Here’s why

It was the last hour of a 30-hour dive, nearly two murky miles below the ocean’s surface.

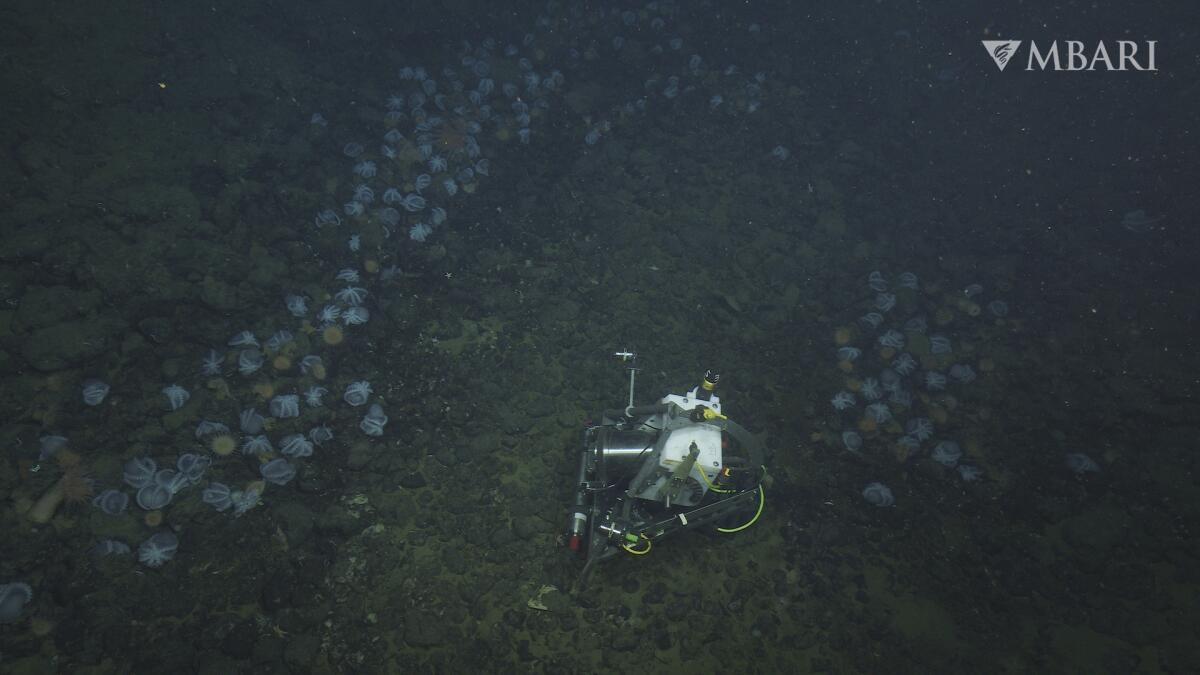

A remotely operated vehicle called the Hercules was exploring the foothills of the Davidson Seamount, an underwater volcano about 90 miles southwest of Monterey. Aboard the boat carrying researchers monitoring the Hercules, it was expected to be a fairly boring dive, said Chad King, the chief scientist on the 2018 cruise. Much research had been done near the top and slope of the seamount, but King and his fellow scientists wanted to explore around its base, expecting to find little sponges or corals amid lots of seafloor muck.

But then, just as Hercules crossed over a ridge, a curious sight floated across the screen: small, almost iridescent bulbs clinging to the seamount wall. The scientists directed Hercules down, farther into the depths.

“And sure enough, that’s where we ran into thousands and thousands of these octopus,” King said. “And we were just absolutely floored. We were just giddy.”

The scientists, led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, had alighted upon what they called an “octopus garden.” The images they captured revealed nearly 6,000 octopuses — leading scientists to estimate the total population of the area could exceed 20,000.

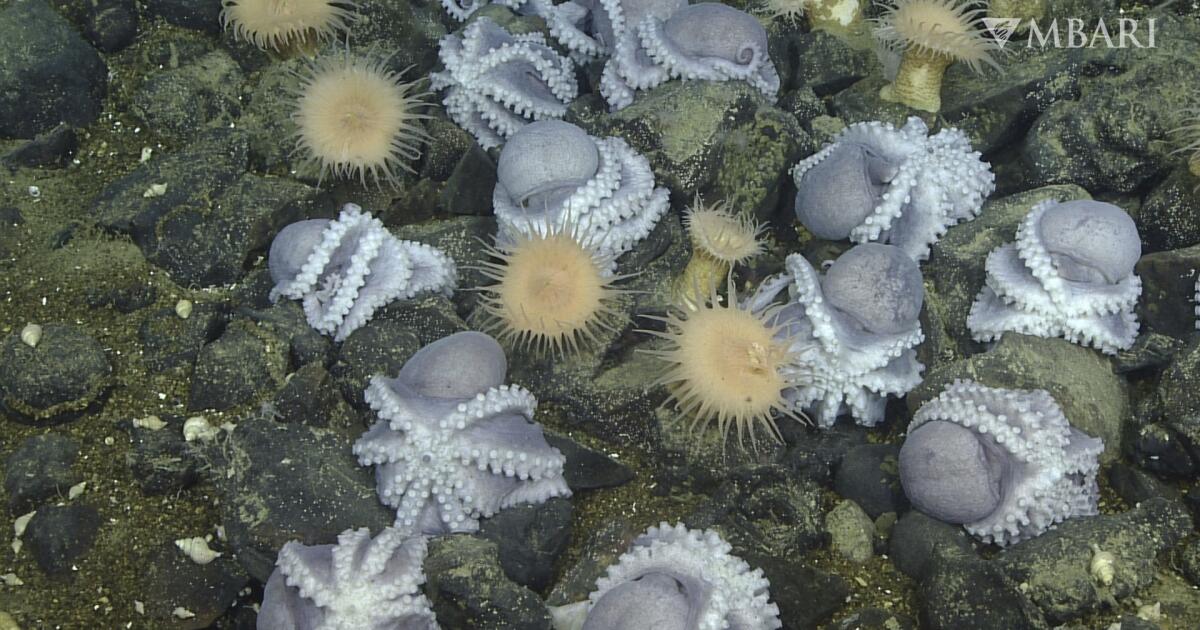

The discovery of the thousands of Muusoctopus robustus — or “pearl octopus,” as researchers dubbed it for the animal’s shape and opalescent shine — led a team of scientists on a five-year quest to solve the mystery: Why are there so many thousands of pearl octopuses at the foot of the Davidson Seamount, and how were they living there?

The researchers visited Octopus Garden more than a dozen times to find out, and a study published last week in the journal Science Advances shows they solved one part of the mystery. The pearl octopus came to the Davidson Seamount, they discovered, to nestle into the warm crooks of its wall and brood baby octopuses.

The ambient temperature of water around the seamount is about 35 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute scientists. But by using sophisticated marine thermometers, the researchers found that the octopuses were settling into crevices warmed by spring water, where the temperature reached nearly 51 degrees.

“So we’re still unsure exactly about what kind of geological circulation drives these springs, but essentially water’s getting heated somewhere underground there,” said Steve Litvin, marine ecologist at the institute. “And just like a warm spring, you know, I don’t want to say ‘Old Faithful,’ but it’s bubbling up there out of the rocks.”

A female pearl octopus broods her eggs near the Davidson Seamount off California.

(Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute)

The relatively warm spring water raises the mother octopus’ metabolism, speeding up the egg development process. Researchers found that octopus eggs in the area hatch in less than two years — far less than the estimated five to eight years it takes in colder temperatures.

“They’re in warm water, the metabolism is much faster,” King said, “so their life history has been very compressed relative to most deep-sea animals.”

Solving one mystery only ignited a burst of other questions for the scientists: Where did the octopus come from? Do they instinctively know that the warm waters will speed up the brooding process? How many other octopus nurseries exist on the seafloor around the world?

“We know so little about the deep ocean,” Litvin said. “The discovery of the garden and all these thousands of octopus … just highlights that this is the biggest ecosystem on our planet, and we know less about it than we know about the surface of the moon.”

Scientists still don’t know where the grapefruit-sized octopuses came from, or how they knew to settle against the Davidson Seamount’s warm rocks. But over years of monitoring them, they watched the octopuses mate, settle, brood and hatch new offspring.

Once an egg is hatched, the mother octopus dies. Shrimps, snails, anemones and other organisms feed off the octopus’ carcass. Most deep-sea animals rely on food floating down from the ocean surface — “marine snow,” Litvin called it. But with such a large number of octopuses living and dying in one area, he said, they provide the seafloor community “about 70% more carbon, more food than if only that marine snow was coming down.”

A time-lapse camera monitors aggregations of female pearl octopuses nesting at the Octopus Garden.

(Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute)

“You wouldn’t see this specific ecosystem at the garden,” Litvin said, “if it wasn’t for all those octopus dying.”

Once a new octopus is hatched, the juvenile swims off into the darkness, Litvin said. Where does it go? That’s a question for future research to answer, he said.

“That’s the largest aggregation of octopus in the world,” Litvin said. “So the thought that these kinds of ecosystems are still hiding from us — that after a couple of decades of a lot of deep-sea exploration, there’s still that scale of a discovery — is just amazing, and really highlights the need for continued investment in technology so we can expand our efforts to explore the deep sea, find the next Octopus Garden and literally, again, understand how that biggest ecosystem in our planet works.”

Science

What to know about chronic venous insufficiency — President Tump's health diagnosis

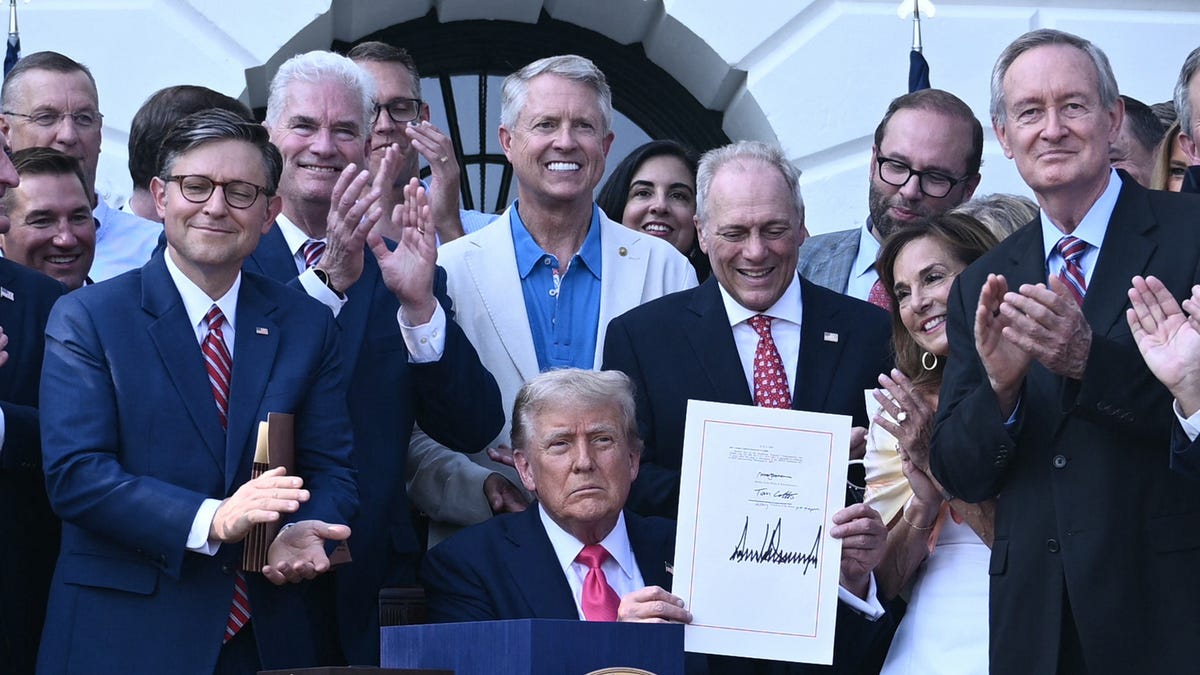

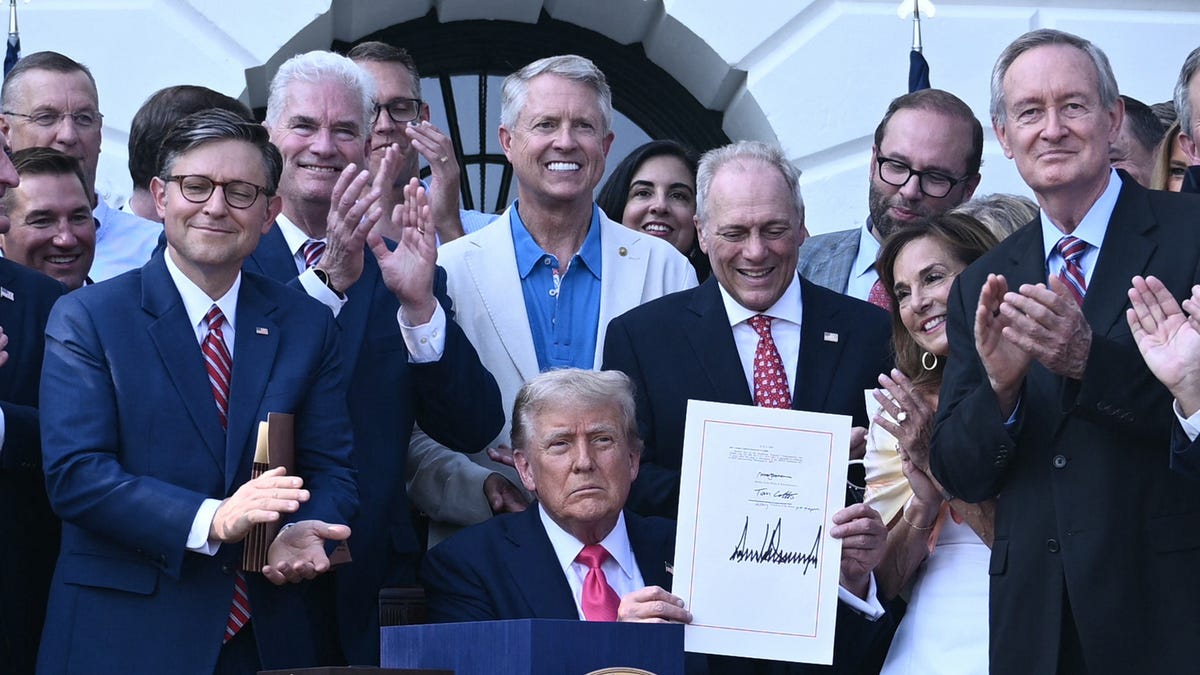

Earlier this week, President Trump was diagnosed with chronic venous insufficiency, or CVI, after he noted mild swelling in his lower legs. White House physician Dr. Sean P. Barbabella in a memo July 17 said the swelling prompted a full medical evaluation, including ultrasound tests and blood work. Those confirmed CVI, a condition the doctor described as “benign and common — particularly in individuals over the age of 70.”

Barbabella said he found no other signs of more serious cardiovascular issues like blood clots and declared the president to be in “excellent health.”

What is chronic venous insufficiency?

“CVI is when the veins of the body do not work well,” said Dr. Mimmie Kwong, assistant professor of vascular surgery at UC Davis Health, when veins cannot transport blood effectively, causing it to pool, especially in the legs.

CVI is one of the most common vein problems in the U.S. and worldwide, affecting “about one in three adults in the United States,” Kwong said.

That translates to more than 30 million people in the U.S., most often older adults, according to Dr. Ali Azizzadeh, a professor and director of Vascular Surgery at Cedars-Sinai and associate director of the Smidt Heart Institute. He noted the condition is more common in women.

As people age, the veins, such as in their legs, may have a harder time returning blood to the heart, he said.

What causes CVI?

The valves in the veins of the legs are supposed to keep blood moving in one direction: back toward the heart. But when those valves are damaged or weakened, they can stop working properly, leading blood to flow backward and collect in the lower legs.

Individuals who stand or sit for extended periods, or those with a family history of vein issues, may be at a higher risk of developing the condition.

“When the calf muscles are active, they pump the veins that return blood from the legs to the heart,” Azizzadeh explained. “With prolonged inactivity of those muscles, blood can pool in the legs.”

What does CVI feel like?

While CVI isn’t always painful, it can cause discomfort that worsens as the day goes on.

The mornings may feel the best: “The legs naturally drain while you are lying down and sleeping overnight,” said Azizzadeh, “so they will typically feel lightest in the morning.”

As the day progresses and blood starts to pool, people with CVI may experience swelling, heaviness, aching or a dull pain in their legs. The symptoms tend to worsen after prolonged periods of standing or sitting.

If swelling worsens, thickening, inflammation or dry skin can result, with more severe cases developing wounds that do not heal and can even result in amputation, Kwong said.

FILE – President Donald Trump speaks to the media as he leaves the White House, July 15, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta, File)

(Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP)

How is CVI treated?

Treatment is more manageable when problematic veins are closer to the surface of the skin, Kwong said. It’s more problematic when deep veins are affected.

The first line of treatment is usually simple lifestyle changes. “We suggest CEE: compression, elevation, and exercise,” Azizzadeh said. Wearing compression stockings can help push blood out of the legs; elevating the legs allows gravity to help drain blood from the legs toward the heart, and regular walking forces calf muscles to pump blood throughout the body.

For people with more serious cases, doctors may recommend a minimally invasive procedure that uses heat to seal off the leaky veins. Common treatments include ablation techniques, surgical removal of veins (phlebectomy), or chemical (sclerosant) injections. “All of these therapies aim to cause the veins to shut down, so they no longer cause the CVI,” Kwong said.

President Trump, left, reaches to shake hands with Bahrain’s Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa.

(Alex Brandon / Associated Press)

In Trump’s case, the condition appears to be mild and manageable, his doctor said. Barbabella emphasized there was no cause for concern and that the president remains in good overall health. But for millions of Americans living with CVI, recognizing the symptoms and knowing how to manage them can make a big difference in day-to-day comfort and long-term well-being.

Science

Immigration crackdown could stymie efforts to fight bird flu outbreak, experts fear

As authorities brace for a potential resurgence in bird flu cases this fall, infectious disease specialists warn that the Trump administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants could hamper efforts to stop the spread of disease.

Dairy and poultry workers have been disproportionately infected with the H5N1 bird flu since it was first detected in U.S. dairy cows in March 2024, accounting for 65 of the 70 confirmed infections, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As is the case throughout agriculture, immigrants make up a significant proportion of this workforce and both industry groups and academics say many of these workers probably entered the U.S. illegally. That could spell trouble for a future outbreak of bird flu, infectious disease experts say, making workers reluctant to cooperate with health investigators.

“Most dairy and poultry workers, regardless of their immigration status, are in no way going to be like, ‘hey, government, yeah, of course, check me out, I think I might have H5N1,’” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization in Canada.

“No, they’re going to keep their heads down and be as quiet as possible so that they don’t end up at” an immigration detention center, such as Alligator Alcatraz, she said.

Officials with the U.S. Department of Agriculture didn’t respond to requests for comment. Neither did the California Department of Public Health, which has been on the front line of worker testing and safety — offering $25 gift cards to workers who agree to be tested and providing personal protective equipment to farmers and workers.

“To imply that the Trump Administration’s lawful approach to immigration enforcement is somehow suppressing disease reporting is a leap unsupported by evidence and dismissive of the real work being done by the agency,” a spokesperson for the Health and Human Services Administration said in a statement.

Public health officials say the risk of H5N1 infection to the general public is low. People who work with livestock and wild animals are considered to be at elevated risk.

The Trump administration paused immigration arrests at farms, hospitals and restaurants last month, but later reversed course. This month, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said that there are plenty of able-bodied Americans to perform farm labor and that there would be “no amnesty” for undocumented farmworkers.

Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, said that there are two big risks with the administration’s crackdown.

Dairy and poultry workers are on the front line of the virus, handling both diseased and infected animals. If they are too afraid to report symptoms or get tested, “it increases the risk that someone could die because the medicines need to be given early after onset of symptoms,” she said.

Nuzzo said the crackdown also decreases the likelihood that a pandemic could be detected in its early stages.

“The virus needs to change and become easily transmissible between people to cause a pandemic and we need to know about as many infections as possible to track the virus and prevent it from gaining those abilities,” Nuzzo said. “[If] people don’t come forward, we can’t do that.”

In the spring, eight undocumented workers at a Vermont dairy were arrested; four were ultimately deported. The raids sent shock waves through the small, tight-knit dairy industry of New England and sent a message to dairies elsewhere that no place is safe.

Anja Raudabaugh, chief executive of Western United Dairies, California’s largest dairy trade association, said dairy farmers aren’t worried about bird flu, adding that measures are in place to protect workers and to prevent a rapid spread of disease.

From a public health perspective, she said, the state is better positioned than it was last year.

“One of the biggest changes in the ground response to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) is that the occupational health clinics, ERs, and other rural clinics now have access to the testing equipment necessary to detect the virus (where they didn’t last year),” she said in an email. In addition, the state’s health department has provided the anti-viral medication, Tamiflu, to health clinics “so the workers feel reinforced that their families can be protected.”

The dairy trade group also has no objections to the immigration crackdown.

“America wants this problem solved and dairy farmers are ready to be part of the solution,” Raudabaugh said. “We do not fear ICE. These are good, full-time jobs and we hire anyone who loves cows and wants to work in a quiet, blue-collar family environment.”

Dairy farmer Joey Airoso said the effect on both his workers and cows was minimal when his Pixley dairy was hit by the virus last year.

His bigger concern is “the wide open border that’s let a lot of people into are country that are here for the wrong reasons,” said Airoso, who owns about 2,600 head of cattle.

But Raw Farms dairy owner Mark McAfee said he and his neighboring farmers in Fresno County are “freaked out” by the ICE raids and “want no part of it.”

McAfee’s dairy, which produces raw milk, was shut down by the virus for several months last year. He’s worried not only about the virus returning, but also about immigration agents seizing his workers, many of whom are foreign born.

“Everybody we have is legal, but they (ICE) don’t give a damn about that — they’re picking them up, too,” he said. “Legal status doesn’t mean a lot, and that’s really scary, because that’s something we all relied upon for previous 25 years of operation.”

One question is whether the state will face another big outbreak of bird flu.

There have been only sporadic infections this summer. Detections of the virus in wastewater is low, and in the last 30 days, only two dairy herds — one each in California and Arizona — and one commercial poultry flock in Pennsylvania have reported outbreaks.

But most experts agree that’s likely to change as migrating birds congregate in fields and around lakes as they journey south later this year — passing virus between one another and infecting young birds with no immunity.

“We have 60,000 waterfowl in California right now,” said Maurice Pitesky, a poultry expert at UC Davis. “By late fall, early winter, that number will jump to 6 million.”

Waterfowl — ducks and geese — are considered the primary carriers of the virus.

Since the virus reappeared in North America at the end of 2022, new variants and widespread outbreaks have followed the migrating birds — infecting poultry farms, resident wild birds, wild mammals, such as racoons, mountain lions and skunks, as well as marine and domestic mammals.

In late 2023, the virus made a jump into dairy cattle. And in the fall of 2024, a new variant — the D1.1 version of the virus — sparked a new outbreak in dairy cows, poultry and other animals.

Andrew Ramey, director of the Molecular Ecology Lab at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Alaska Science Center, which monitors for H5N1 in wild bird populations, said one possibility is that the bird flu could return in a more virulent state.

“I think we’re all kind of bracing to see what might happen this fall,” he said.

Science

The mother of an L.A. teen who took his own life is fighting for a new mental health tool for LGBTQ+ youth

Bridget McCarthy believes that if her son Riley Chart had quick and easy access to a suicide prevention hotline designed for queer young people, he might be alive today.

Chart, a trans teen who had once endured bullying because he was different, took his own life at the family’s home during the COVID-19 lockdown in September 2020 — two weeks after his 16th birthday.

“I truly believe that had there been an LGBTQ-specific [help] number right in front of him, he would’ve tried it,” McCarthy said.

Riley Chart with his mother Bridget McCarthy.

(Paul Chart)

State lawmakers are set to vote in August on a bill that McCarthy and its sponsors say could save the lives of other young queer Californians.

California Assembly Bill 727 would require ID cards for public school students in grades 7 through 12 and students at public institutions of higher education to list the free LGBTQ+ crisis line operated by The Trevor Project on the back, starting in July 2026.

The Trevor Project is a West Hollywood-based nonprofit that the federal government cut ties with when it eliminated funding for LGBTQ+ counseling through the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (9-8-8). The lifeline was expected to stop routing crisis calls to The Trevor Project and six other LGBTQ+ contractors Thursday. It’s one of several actions in the second Trump administration that critics fear will roll back years of progress of securing health-care services for queer Americans.

“When the Trump administration threatened and then went through with their threat to cut the program completely, that told us that we had to step up to the plate,” said Democratic Assemblymember Mark González of Los Angeles, who said he introduced the legislation to ensure that queer youth receive support from counselors who can relate to their life experiences. “Our goal here is to be the safety net — especially for those individuals who are not in Los Angeles but in other parts of the state who need this hotline to survive.”

California Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis, the L.A. LGBT Center and the Sacramento LGBT Center all have signed on as co-sponsors of the bill. Gov. Gavin Newsom told Politico the Trump administration’s 9-8-8 decision was “indefensible” and that he also backs the bill. His office said the state’s $4.7 billion Master Plan for Kids’ Mental Health includes partnerships with organizations such as The Trevor Project.

González said the bill originally included private schools but in response to conservative opposition, the mandate was amended so it would be limited to public schools.

With federal funding for the LGBTQ+ crisis counselors who field calls through the 9-8-8 lifeline running out on Thursday, local nonprofits and elected officials have vowed to fill the void. L.A. County Supervisors Janice Hahn and Lindsey P. Horvath authored a motion to explore the impact of the cut and see whether the county can help to continue the service. The board unanimously approved it Tuesday.

“The federal government may be turning its back on LGBTQ+ people, but here in L.A. County we’ll do everything within our power to keep this community safe,” Hahn said in a statement after the vote.

About 40% of young queer people in the U.S. have seriously contemplated suicide compared to 13% of their peers, according to a teen mental health survey published last fall by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Trevor Project and other organizations have reported a rise in the number of people calling crisis lines to seek mental health support, both in California and nationwide.

Trans Americans have been particularly shaken by the backlash against LGBTQ+ people and by the prospect of new restrictions on gender-affirming healthcare, according to new findings published this week by researchers at the University of Vermont.

Their survey of 489 gender-diverse adults after the 2024 election, published Wednesday in JAMA Open Network, found that nearly a third of those interviewed would consider risky DIY hormone therapies if treatments disappear elsewhere. A fifth of respondents reported having suicidal thoughts.

Riley Chart with his father, Paul Chart.

(Bridget McCarthy)

As the mother of a trans child who died from suicide, McCarthy said she wants to use the lessons she’s learned to educate and advocate for other trans young people and their families in similar situations.

McCarthy, who lives in Culver City, has started a memorial fund with The Trevor Project, organized suicide prevention walks in West L.A. and attended Pride festivals to hand out crisis line information.

She remembers Riley as an artistic and warmhearted son who joined LGBTQ+ groups and built a network of friends while attending high schools in both Santa Monica and Culver City.

Riley had a therapist for support living as a trans teen, but during the pandemic, he found it hard to cope with not being able to spend time in person with his friends. The confinement made him increasingly irritable. He was staying up later than usual and spending excessive time on his phone, McCarthy said.

After Riley died, the family discovered that he’d texted a gay friend for help.

“The only other number in his phone was a 10-digit veterans hotline number — that he did not call,” McCarthy said. “That’s why you have to have a lifeline that speaks to different populations. A veterans hotline will not work for a 16-year-old kid who’s struggling with their identity.”

When Riley was 12, McCarthy took him to the Pride parade in West Hollywood hoping that he would experience the feeling of belonging that he seemed to yearn for. He loved it.

Riley Chart attending West Hollywood Pride in 2017.

(Bridget McCarthy)

“Ry said he’d found his people,” McCarthy recalls, using the family’s nickname for him. “He was like, ‘This is it — I’m home, mom.’”

When Riley’s mother took him to Pride a second time the following year, he bought a trans pride flag that became one of his prized possessions. “He was wrapped in it when he went, when he left us,” McCarthy said.

McCarthy spoke by phone from one of Riley’s favorite places, Lummi Island in Washington state, near the U.S.-Canada border. The family laid Riley’s remains on the island and McCarthy goes to visit the grave site four times a year to care for the maple tree planted in his memory, admire the painted stones his friends placed around it and talk to her son.

McCarthy said she and Riley visited family friends on the island almost every year when he was younger. Especially during middle school when he faced bullying from classmates and issues over which restroom to use, the island served as a refuge where McCarthy saw her son at his most carefree. He loved climbing trees, swimming and herding cows, far from the pressures of being a kid in L.A.

“When you’d open the car door, it was just like opening the barn gate,” McCarthy remembers. “Like a colt across a field, he would just run. It gave us a chance for some peace.”

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week ago8 ways Trump’s ‘Big, Beautiful Bill’ will affect Iowans, from rural hospitals to biofuels

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoConstitutional scholar uses Biden autopen to flip Dems’ ‘democracy’ script against them: ‘Scandal’

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDOJ rejects Ghislaine Maxwell’s appeal in SCOTUS response

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoNew weekly injection for Parkinson's could replace daily pill for millions, study suggests

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTest Your Knowledge of French Novels Made Into Musicals and Movies

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSCOTUS allows dismantling of Education Dept. And, Trump threatens Russia with tariffs

-

Business1 week ago

Musk says he will seek shareholder approval for Tesla investment in xAI

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoEx-MLB pitcher Dan Serafini found guilty of murdering father-in-law