Science

Just Between Us Squirrels, There Might Be Trouble in the Arctic Dating Scene

Male Arctic ground squirrels go through puberty every year. As if that wasn’t hard enough, now the females have a problem, too.

According to a paper published on Thursday in the journal Science, climate change appears to be making them emerge from hibernation earlier. That matters, because it could throw off the timing of the animals’ mating cycle.

Typically, males come out of hibernation before females to prepare for the spring mating season. They need time to reach sexual maturity again, every year, because their testosterone levels drop sharply during the winter.

Then, the females wake up. But scientists have found that as temperatures rise, female ground squirrels are emerging up to 10 days earlier than they used to. Researchers think it has to do with earlier thawing of the soil.

The hibernation pattern of the males, meanwhile, does not appear to be changing.

“This study suggests that males and females of the same species can respond differently to climate change,” said Helen E. Chmura, a research ecologist with the United States Forest Service who was lead author on the paper. “This could have important implications for reproduction.”

The squirrels’ troubles are part of a much larger crisis. Around the world, wildlife is struggling. On land, the main cause is humans taking over too much of the planet, erasing the biodiversity that was there before. In the oceans, the main problem is overfishing. Climate change is making survival even more difficult.

For now, Arctic ground squirrels are still plentiful in the wild. The International Union for Conservation of Nature classifies them as a species of least concern, meaning that they are not threatened or in need of conservation efforts. But the paper says the new hibernation mismatch “has the potential to affect their survival probability.”

Any decline in squirrel populations could disrupt the local food web. Almost all Arctic predators, from wolves to eagles, rely on them as a food source.

Although the Arctic is warming faster than any other region on Earth, there is relatively little research on how this heating is affecting animals. This new paper, which covers more than 25 years in Northern Alaska, is one of the first long-term research projects to present strong evidence that warming is directly changing the physiological processes of Arctic species.

“This study is relatively unusual because it shows that warming is directly impacting a mammal,” said Cory T. Williams, an assistant professor at Colorado State University and a co-author of the study. “Some people might say, ‘OK, a 10-day advance over 25 years doesn’t seem that fast.’ But in terms of climate, that’s incredibly fast.”

Arctic ground squirrels might look cute, but males can be very territorial. They get into a lot of fights during mating season, some deadly. They have tails, but not long, bushy ones like squirrels found farther south. And they make distinctive whistling noises that could easily be mistaken for the chirp of a small bird. Some Alaska Natives call them parka squirrels because their fur makes a nice, warm fringe for the hood of a coat.

Scientists have long been interested in their hibernation patterns.

During the long winter sleep, the squirrels’ core body temperature can drop to about 27 degrees Fahrenheit, or roughly minus 3 Celsius, with their resting heart rate falling as low as three beats per minute. More knowledge about that process could lead to advances in therapeutic hypothermia, a medical treatment in which the body temperature is lowered to prevent injury. It’s sometimes used after cardiac arrest.

But the most pressing challenge, scientists say, is getting a grip on the changes happening in the Far North.

“The big gap is just understanding what is happening in the Arctic in general,” Dr. Williams said. “This study shows why we need long-term projects to understand the changes happening across different levels.”

Science

Q&A: Learn how Olympians keep their cool from Team USA's chief sports psychologist

Your morning jog or weekly basketball game may not take place on an Olympic stage, but you can use Team USA’s techniques to get the most out of your exercise routine.

It’s not all about strength and speed. Mental fitness can be just as important as physical fitness.

That’s why the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee created a psychological services squad to support the mental health and mental performance of athletes representing the Stars and Stripes.

“I think happy, healthy athletes are going to perform at their best, so that’s what we’re striving for,” said Jessica Bartley, senior director of the 15-member unit.

Bartley studied sports psychology and mental health after an injury ended her soccer career. She joined the USOPC in 2020 and is now in Paris with Team USA’s 592 competitors, who range in age from 16 to 59.

Bartley spoke with The Times about how her crew keeps Olympic athletes in top psychological shape, and what the rest of us can learn from them. Her comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Why is exercise good for mental health?

It gets you moving. It gets the endorphins going. And there’s often a lot of social aspects that are really helpful.

There are a number of sports that stretch your brain in ways that can be really, really valuable. You’re thinking about hand-eye coordination, or you’re thinking about strategy. It can improve memory, concentration, even critical thinking.

What’s the best way to get in the zone when it’s time to compete?

When I work with athletes, I like to understand what their zone is. If a 0 or a 1 is you’re totally chilled out and a 10 is you’re jumping around, where do you need to be? What’s your number?

People will say, “I’m at a 10 and I need to be at an 8 or a 7.” So we’ll talk about ways of bringing it down, whether it’s taking a deep breath, listening to relaxing music, or talking to your coach. Or there’s times when people say they need to be more amped up. That’s when you see somebody hitting their chest, or jumping up and down.

If you make a mistake in the middle of a competition, how do you move on instead of dwelling on it?

I often teach athletes a reset routine. I played goalie, so I had a lot of time to think after getting scored on. I would undo my goalie gloves and put them back on, which to me was a reset. I would also wear an extra hairband on my wrist, and when I would snap it, that meant I needed to get out of my head.

It’s not just a physical reset — it helps with a mental reset. If you do the same thing every single time, it goes through the same neural pathway to where it’s going to reset the brain. That can be really impactful.

Do Olympic athletes have to deal with burnout?

Oh, yeah. Everybody has a day where they don’t want to do whatever it is. That’s when you have to ask, “What’s in my best interests? Do I need a recovery day, or do I really need to get in the pool, or get in the gym?”

Sometimes you really do need what we like to refer to as a mental health day.

How can you psych yourself up for a workout when you just aren’t feeling it?

It’s really helpful to think about why you’re doing this and why you’re pushing yourself. Do you have goals related to an activity or sport? Is there something tied to values around hard work or discipline, loyalty or dependability?

When you don’t want to get in the gym, when you don’t want to go for a run, think about something bigger. Tie it back to values.

Is sleep important for maintaining mental health?

Yes! We started doing mental health screens with athletes before the Tokyo Games. We asked about depression, anxiety, disordered eating and body image, drugs and alcohol, and sleep. Sleep was actually our No. 1 issue. It’s been a huge initiative for us.

How much sleep should we be getting?

It’s different for everyone, but generally we know seven to nine hours of sleep is good. Sometimes some of these athletes need 10 hours.

I highly recommend as much sleep as you need. If you didn’t get enough sleep, napping can be really valuable.

Is napping just for Olympic athletes or is it good for everybody?

Everybody! Naps are amazing.

What if there’s no time for a nap?

There are different ways of recharging. Naps could be one of them, but maybe you just need to get off your feet for 20 minutes. Maybe you need to do a meditation or mindfulness exercise and just close your eyes for five minutes.

How do you minimize the effects of jet lag?

We try to shift one hour per day. That’s the standard way of doing it. If you can, it’s super helpful. But it’s not always possible.

The thing we tell athletes is that our bodies are incredible, and you will even things out if you can get back on schedule. One or two nights of crummy sleep is not going to impact your overall performance.

What advice do you give athletes who have trouble falling asleep the night before a competition?

You don’t want to change much right before a competition, so I usually direct athletes to do what they would normally do.

Do you need to unwind by reading a book? Do you need to talk on the phone with somebody and get your mind off things? Can you put your mind in a really restful place and think about things that are really relaxing?

Are there any mindfulness or meditation exercises that you find helpful?

There are some athletes who benefit greatly from an hourlong meditation. I love something quick, something to reset my brain, maybe close my eyes for a minute.

If I’m feeling like I need to take a moment, I love mindful eating. You savor a bite and go, “Oh, my gosh, I have not been fully engaged with my senses today.” Or you could take a mindful walk and take in the sights, the smells, all of the things that are around you.

What do you eat when you need a quick nutrition boost?

Cashews. I tend to carry those with me. They’ve got enough energy to make sure I keep going, physically.

I’ve always got gummy bears on me too. There’s no nutritional value but they keep me going mentally. I’m a big proponent of both.

Is it OK to be superstitious in sports?

It depends how flexible you are. Maybe you put on your socks or shoes a certain way, or listen to certain music. Routines are really soothing. They set your brain up for success in a particular performance. It can be really, really helpful.

But I’ve also seen an athlete forget their lucky underwear or their lucky socks, and they’re all out of sorts. So your routine has to be flexible enough that you’re not going to completely fall apart if you don’t do it exactly.

Are Olympians made of stronger psychological stuff than the rest of us?

Not necessarily. There are some who don’t get feathers ruffled and have a high tolerance for the fanfare. There’s also a lot of regular human beings who just happen to be fantastic at a particular activity.

Science

‘Ready, Steady, Slow’: Championship Snail Racing at 0.006 M.P.H.

Earlier this month, the rural village of Congham, England, played host to a less likely group of athletes: dozens of garden snails. They had gathered to compete in the World Snail Racing Championships, where the world record time for completing the 13.5 inch course stands at 2 minutes flat. At that speed — roughly 0.006 miles per hour — it would take the snails more than six days to travel a mile.

Science

Caring for condor triplets! Record 17 chicks thrive at L.A. Zoo under surrogacy method

A new method of rearing California condors at the Los Angeles Zoo has resulted in a record-breaking 17 chicks hatched this year, the zoo announced Wednesday.

All of the newborn birds will eventually be considered for release into the wild under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s California Condor Recovery Program, a zoo spokesperson said.

“What we are seeing now are the benefits of new breeding and rearing techniques developed and implemented by our team,” zoo bird curator Rose Legato said in a statement. “The result is more condor chicks in the program and ultimately more condors in the wild.”

Breeding pairs of California condors live at the zoo in structures the staff “affectionately calls condor-miniums,” spokesperson Carl Myers said. When a female produces a fertilized egg, the egg is moved to an incubator. As its hatching approaches, the egg is placed with a surrogate parent capable of rearing the chick.

California condor eggs are cared for at L.A. Zoo. The animal is critically endangered.

(Jamie Pham / L.A. Zoo)

This bumper year of condor babies is the result of a modification to a rearing technique pioneered at the L.A. Zoo.

Previously, when the zoo found itself with more fertilized eggs than surrogate adults available, staff raised the young birds by hand. But condors raised by human caretakers have a lower chance of survival in the wild (hence the condor puppets that zookeepers used in the 1980s to prevent young birds from imprinting on human caregivers).

In 2017, the L.A. Zoo experimented with giving an adult bird named Anyapa two eggs instead of one. The gamble was a success. Both birds were successfully released into the wild.

Faced with a large number of eggs this year, “the keepers thought, ‘Let’s try three,’” Myers said. “And it worked.”

The zoo’s condor mentors this season ultimately were able to rear three single chicks, eight chicks in double broods and six chicks in triple broods. The previous record number of 15 chicks was set in 1997.

Condor experts applauded the new strategy.

“Condors are social animals and we are learning more every year about their social dynamics. So I’m not surprised that these chick-rearing techniques are paying off,” said Jonathan C. Hall, a wildlife ecologist at Eastern Michigan University. “I would expect chicks raised this way to do well in the wild.”

The largest land bird in North America with an impressive wingspan up to 9½ feet, the California condor could once be found across the continent. Its numbers began to decline in the 19th century as human settlers with modern weapons moved into the birds’ territory. The scavenger species was both hunted by humans and inadvertently poisoned by lead bullet fragments embedded in carcasses it ate. The federal government listed the birds as an endangered species in 1967.

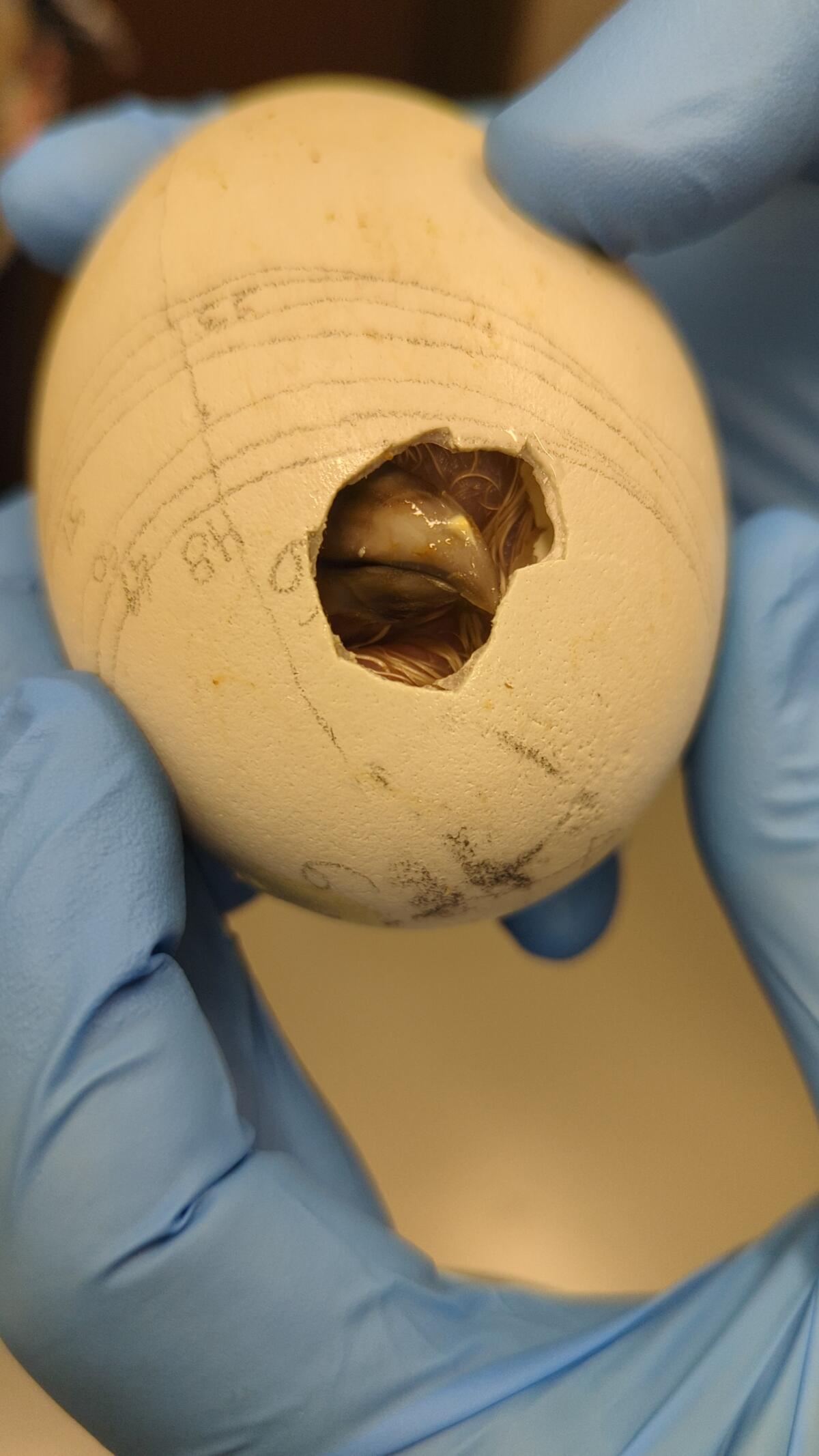

A condor, one of a record-breaking 17 at the zoo, makes its way out of its shell.

(Jamie Pham / L.A. Zoo)

When the California Condor Recovery Program began four decades ago, there were only 22 California condors left on Earth. As of December, there were 561 living individuals, with 344 of those in the wild. Despite the program’s success in raising the population’s numbers, the species remains critically endangered.

In addition to the ongoing threat of lead poisoning, the large birds are also at risk from other toxins. One 2022 study found more than 40 DDT-related compounds in the blood of wild California condors — chemicals that had made their way from contaminated marine life to the top of the food chain.

“Despite our success in returning condors to the wild, free-flying condors continue to face many obstacles with lead poisoning being the No. 1 cause of mortality,” said Joanna Gilkeson, spokesperson for Fish and Wildlife’s Pacific Southwest Region. “Innovative strategies, like those the L.A. Zoo is implementing, help us to produce more healthy chicks and continue releasing condors into the wild.”

The chicks will remain in the zoo’s care for the next year and a half before they are evaluated for potential release to the wild. Thus far, the zoo has contributed 250 condor chicks to Fish and Wildlife’s program, some of which the agency has redeployed to other zoos as part of its conservation efforts.

In a paper published earlier this year, a team of researchers found that birds born in captivity have slightly lower survival rates for their first year or two but then have equally successful outcomes to wild-hatched birds.

“Because condors reproduce slowly, releases of captive-bred birds are essential to the recovery of the species, especially in light of ongoing losses due to lead-related mortality,” said Victoria Bakker, a quantitative ecologist at Montana State University and lead author of the paper. “The team at the L.A. Zoo should be recognized for their innovative and important contributions to condor recovery.”

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoOne dead after car crashes into restaurant in Paris

-

Midwest1 week ago

Midwest1 week agoMichigan rep posts video response to Stephen Colbert's joke about his RNC speech: 'Touché'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Young Republicans on Why Their Party Isn’t Reaching Gen Z (And What They Can Do About It)

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: A new generation drives into the storm in rousing ‘Twisters’

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics: The Call is Coming from Inside the House

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIn Milwaukee, Black Voters Struggle to Find a Home With Either Party

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: J.D. Vance Accepts Vice-Presidential Nomination

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrump to take RNC stage for first speech since assassination attempt