Science

'I don't want him to go': An autistic teen and his family face stark choices

Christine LyBurtus was aching and fearful of what might happen when her 13-year-old son returned home.

Noah had been sent to Children’s Hospital of Orange County for a psychiatric hold lasting up to 72 hours after he punched at walls, flipped over a table, ripped out a chunk of his mother’s hair and tried to break a car window.

“There’s nothing else to call it except a psychotic episode,” LyBurtus said.

The clock was ticking on that August day in 2022. The single mother wanted help to prevent such an episode from happening again, maybe with a different medication. Hospital staff were waiting for a psychiatric bed, possibly at another hospital with a dedicated unit for patients with autism or other developmental disabilities.

But as the hours ran out on the hold, it became clear that wasn’t happening. LyBurtus brought Noah home to their Fullerton apartment.

“When he came back home, it kind of broke my heart,” said his sister, Karissa, who is two years older. “He looked like, ‘What the heck did you guys put me into?’”

Christine LyBurtus makes a snack for Noah.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The next night, Noah was back in the ER after smashing a television and attacking his mother. This time, he was transferred to a different hospital for three weeks, prescribed medications for psychosis, and then sent to a residential facility in Garden Grove.

LyBurtus said she was told it would be a stopgap measure — just for three weeks — until she could line up more help at home. But when she phoned to ask about visiting her son, LyBurtus said she was told she couldn’t see him for a month.

“He lives here now,” someone told her, she said, and the staff needed time to “break him in.”

LyBurtus felt like she was being pushed to give up her son, instead of getting the help her family needed. She insisted on bringing him home.

::

Autism is a developmental condition that can shape how people think, communicate, move and process sensory information. When Noah was 3, a doctor noted he was a “very cute little boy” who played alone, rocked back and forth, and sometimes bit himself. Noah’s eye contact was “fleeting.” He could speak about 20 words, but often cried or pulled his mother’s hand to communicate.

The physician summed up his behavior as “characteristic of a DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder.”

When he was in elementary school, LyBurtus stopped working full time outside the home and enrolled in a state program that paid her as his caregiver. She relies on Medi-Cal for his medical care, and much of his schooling has been in Orange County-run programs for children with moderate to severe disabilities.

Noah does not speak but sometimes uses pictures, an app on a tablet, or some sign language to communicate. When a reporter visited their home last year, Noah bobbed his head and shoulders as he listened to music on his iPad. He flapped his hands as LyBurtus made him a peanut-butter-and-banana smoothie, and then dutifully followed her instructions to chuck the peel and put the almond milk away. It was a good day, LyBurtus said with relief.

But on other days, LyBurtus said her son could be rigid; his demands, unpredictable. “Some days he’s fixated on having three pairs of pants on … Some days he wants to take seven showers. The next day, I can’t get him to take showers.”

Christine LyBurtus greets Noah as he arrives home from school.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

When frustrated, Noah might erupt, banging his head against walls and trying to jump out the windows of their apartment. He had kicked and bitten his mother when she tried to redirect him. In the worst instances, LyBurtus had resorted to hiding in the bathroom — her “safe room” — and urged Karissa to lock herself in the bedroom.

As Noah grew taller and stronger, LyBurtus stripped bare the walls of her apartment to try to make it safe, installed shatterproof windows and removed a knob from a closet door to prevent Noah from using it as a foothold to scale over the top of the closet door. She made sure to flag her address for the Fullerton Police Department so it knew her son was developmentally disabled.

“I’m just so grateful that my son never got shot,” LyBurtus said.

Each of the 911 calls was the start of a Sisyphean routine. Noah “has been challenging to place in [a] mental health facility due to behavioral care needs with severe autism,” a doctor wrote when he was back at Children’s Hospital of Orange County yet again.

Noah leaps into the air inside his Fullerton home. At left is Terrence Morris, one of Noah’s caregivers.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

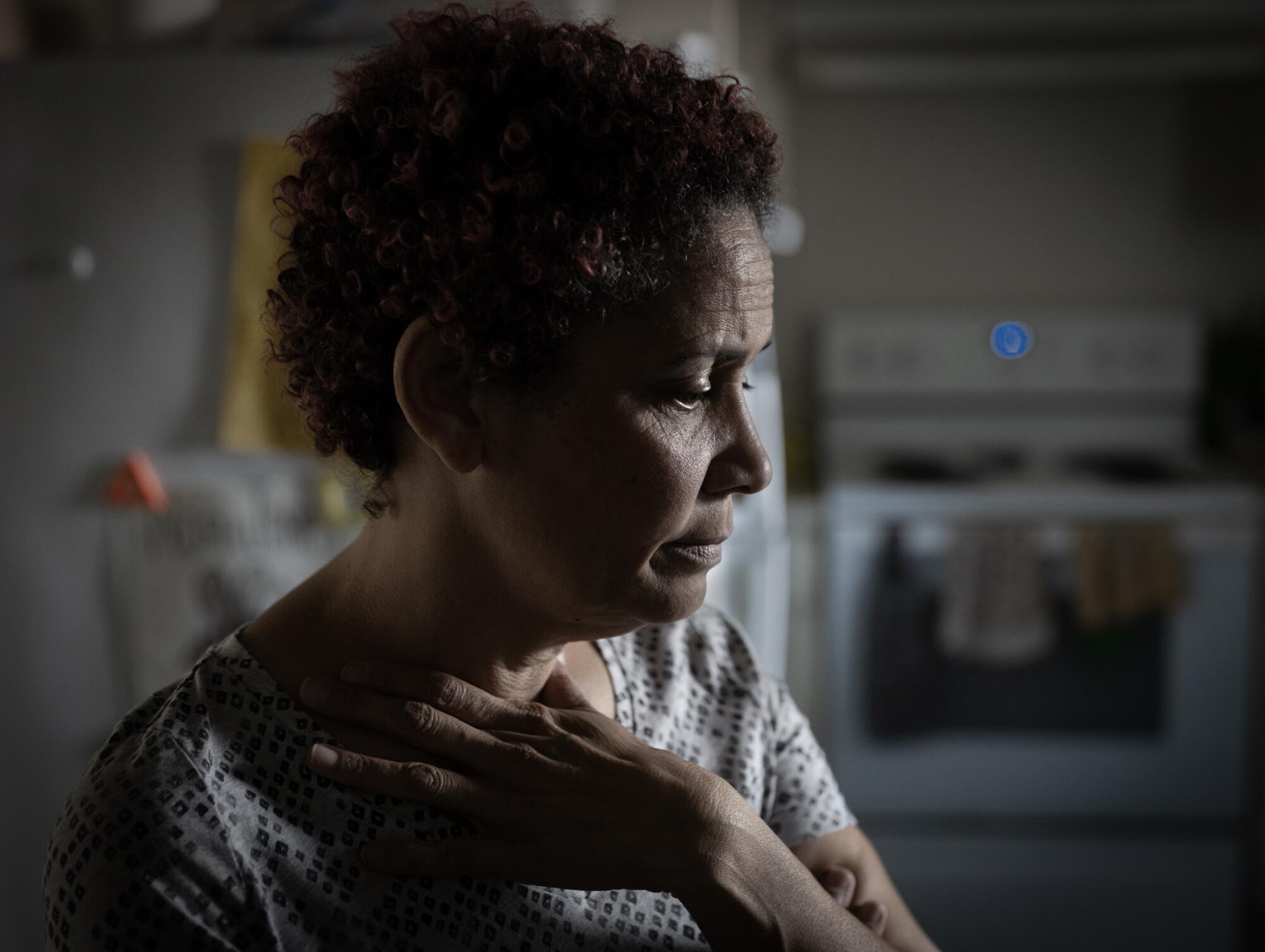

As the family tried to get through each crisis, LyBurtus was also facing a common struggle among parents of California children with disabilities: not getting the help they were supposed to receive from the state.

LyBurtus was getting assistance through a local regional center, one of the nonprofit agencies contracted by the California Department of Developmental Services. She said she’d been authorized to receive 40 hours weekly of respite care — meant to relieve families of children with disabilities for short periods — but was sometimes receiving only 12 to 16 hours.

She was also supposed to have two workers at a time, LyBurtus said, but caregivers were so scarce that she was scheduling one at a time in order to cover as many hours as she could.

In the meantime, Noah wasn’t sleeping and she was going through so much laundry detergent and quarters that her grocery budget was drained. At one point, she wanted to go to a food bank, but there would be no one to watch him.

“I could not be anymore tired and frustrated!!!!” she wrote to her regional center coordinator. “Is the only way Noah is going to get help [is] if I abandoned him and surrender him to the State!?!?”

Christine LyBurtus said she’s struggled to find the right care for Noah.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

::

Across the country, surging numbers of young people have landed in emergency rooms in the throes of a mental health crisis amid a shortage of needed care. Children in need of psychiatric care are routinely held in emergency departments for hours or even days. Even amid COVID, as people tried to avoid emergency rooms, mental health-related visits continued to rise among teens in 2021 and 2022.

Among those hit hardest by the crisis are autistic youth, who turn up in emergency rooms at higher rates than other kids — and are much more likely to do so for psychiatric issues. Many have overlapping conditions such as anxiety, and researchers have also found they face a higher risk of abuse and trauma.

“We’re a misunderstood, marginalized population of people” at higher risk of suicide, Lisa Morgan, founder of the Autism and Suicide Prevention Workgroup, said at a national meeting.

Yet the available assistance is “not designed for us.”

According to the National Autism Indicators Report, more than half of parents of autistic youth who were surveyed had trouble getting the mental health services their autistic kids needed, with 22% saying it was “very difficult” or “impossible.” A report commissioned by L.A. County found autistic youth were especially likely to languish in ERs amid few options for ongoing psychiatric treatment.

Karissa interacts with her brother, Noah, as he watches a video after school.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In decades past, many psychiatrists were unwilling to diagnose mental health disorders in autistic people, believing “it was either part of the autism or for other reasons it was undiagnosable,” said Jessica Rast, an assistant research professor affiliated with the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute. Much more is now known about both autism and mental health treatment, but experts say the two fields aren’t consistently linked in practice.

Mental health providers may focus on an autism diagnosis for a prospective patient and say, “‘Well, that’s not in our wheelhouse. We’re treating things like depression or anxiety,’” said Brenna Maddox, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

Yet patients or their families “weren’t asking for autism treatment. They were asking for depression or anxiety or other mental health treatment,” Maddox said.

In the meantime, the system that serves children with developmental disabilities has faltered.

“Never have I seen that we can’t staff the needed things on so many cases,” Larry Landauer, executive director of the Regional Center of Orange County, said last year. Statewide, “there’s thousands and thousands of cases that are struggling.”

“If I’m a respite worker and I get called on to provide help to families … who am I going to select?” Landauer asked. “The [person] that watches TV and plays on his iPad and I just sit and monitor him? Or do I take someone that is significantly behaviorally challenged — that pulls my hair, that scares me all the time, that tries to run out the door? … Those are the ones getting left out.”

::

The fall and winter of 2022 were so trying that LyBurtus eventually took matters into her own hands. Noah bit his mother and smashed a bathroom window and tried to climb out before the Fullerton Fire Department arrived. Weeks later, LyBurtus had to dial 911 again after he bit his sister’s finger badly enough to draw blood.

Caregiver Terrence Morris, left, keeps a watchful eye on Noah.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

He ended up in a hold at Children’s Hospital of Orange County, which searched for another facility that might help him, but “all placement options declined patient placement,” according to his medical records.

Noah was again sent home with his mother, but the next day, he was back at Children’s Hospital of Orange County after slamming his head against a tile floor.

LyBurtus, frantic and bruised, made call after call and finally used her credit card to pay for an ambulance to take him to UCLA Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital, where he was admitted.

Week by week, psychiatrists there said Noah seemed to be making some strides as they adjusted his alphabet soup of medications. But hospital staff struggled to understand what would set him off.

Once, while playing cards, Noah suddenly started knocking the cards off the table and struck another patient in the face. Another day, he appeared suddenly to be frightened after using the bathroom, and then charged at a computer plugged in nearby.

But there were also days when he danced to a Michael Jackson song, or played Giant Jenga outside on the deck. One day, a doctor wrote, “He made eye contact for a few seconds. I waved to him, and he looked at his hand, as though he was wondering what to do with it in return.”

Christine LyBurtus washes her son’s face. When Noah was 3, a doctor noted he was a “very cute little boy” who played alone, rocked back and forth, and sometimes bit himself.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

LyBurtus was straining to find more help at home so UCLA held off on discharging him, but at the end of January 2023 Noah was sent home. With no changes in medication planned, “and the strong possibility that Noah grew tired of the inpatient setting, the ward no longer was deemed therapeutic or necessary,” a doctor wrote.

Less than a month later, he was back in the emergency room at Children’s Hospital of Orange County after biting and attacking his mother.

A psychiatrist at the pediatric hospital wrote that because he had limited ability to communicate, another round of psychiatric hospitalization would do little unless it was specialized for “individuals with neurodevelopmental needs.” When the 72-hour hold at children’s hospital ran out, LyBurtus asked for an ambulance to take Noah home, fearful of driving him herself.

In May, the month Noah turned 14, LyBurtus heard the regional center had found a place for Noah: a four-bed facility in Rio Linda, a tiny town near Sacramento that she’d never heard of. He could live there for more than a year, she was told, and then hopefully return home with the right support.

Christine LyBurtus shows photographs to Noah.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

But LyBurtus fretted about what she would do if something happened to him so far away. She felt, she said, like she had failed her child. Months passed as they waited for a spot there; LyBurtus said she was told they were trying to hire the needed staff.

“I don’t want him to go,” she said, “but I don’t want to continue going on the way that we’re going on.”

Then in August, LyBurtus was told the regional center had found a spot at a facility much closer to home: the state-run South STAR facility in Costa Mesa, about 20 miles from their apartment. Noah would occupy one of only 15 STAR beds across the state for developmentally disabled adolescents in “acute crisis.”

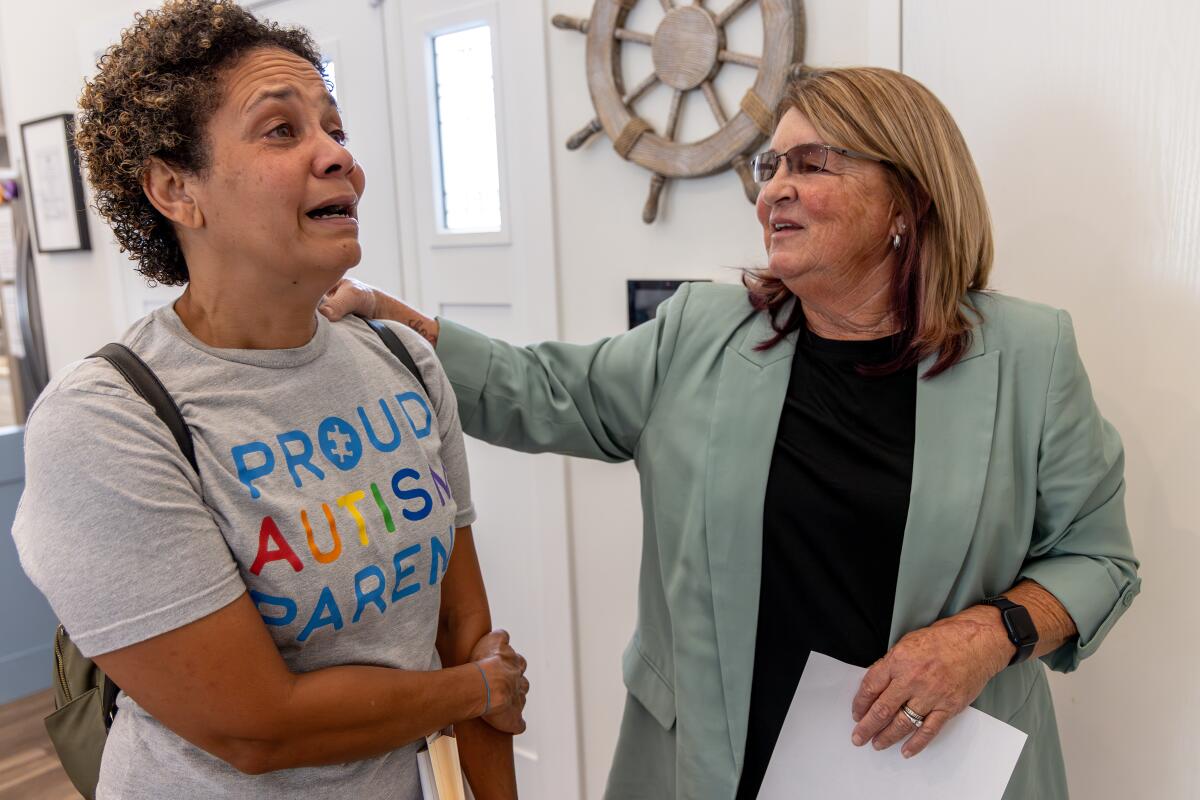

On a bright September morning, LyBurtus pulled up at an unassuming gray house with a “Home Sweet Home” sign by the door. The three teens living there were gone for the morning while an administrator and South STAR program director Kim Hamilton-Royse showed LyBurtus around the house.

Minutes into the tour, LyBurtus found herself crying. Hamilton-Royse stopped her explanation of the daily schedule. “I know this is super hard for you,” she said gently.

But LyBurtus brightened at the sight of the sensory room outfitted with crash pads and a mesmerizing, colorful cylinder of bubbling water. Hamilton-Royse pointed out a vibrating chair and added that they had a projector that would fill the room with illuminated stars.

LyBurtus took photos on her smartphone to show Noah. “You’re not going to be able to get him out of here,” she said.

As they rounded the rest of the house — bedrooms with dressers secured to the wall, a living room with paintings of sailboats, a fish tank — Hamilton-Royse asked if LyBurtus felt any better.

Christine LyBurtus reacts while boxing up items for Noah’s move.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

“I do,” she said. “I just hope that he can behave.”

Hamilton-Royse reassured her that South STAR had never kicked anyone out. “And we’ve had some really challenging folks,” she said.

“I promise you we’ll take very good care of him.”

As she returned to her car, LyBurtus took a deep breath. “It’s hard not to feel like I’m betraying him,” she said, her voice shaking. “But I can’t keep living like this, you know?”

1

2

3

1. Christine Lyburtus tours a residential care facility in Costa Mesa, about 20 minutes from her home. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 2. At the South STAR facility, LyBurtus was told, Noah would occupy one of only 15 STAR beds across the state for developmentally disabled adolescents in “acute crisis.” (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 3. “I just hope that he can behave,” LyBurtus said of son Noah. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Three days later, Noah went back to the Children’s Hospital of Orange County on another psychiatric hold. He came home, then was back in the emergency department a week and a half later.

::

The October night before Noah left home, LyBurtus had brought home sushi for him, one of his favorite foods. He fell asleep around 6:30 p.m, and woke up again at 1 a.m. LyBurtus gave him his medication and as he drifted back to sleep, his mother held him, enjoying the peace.

When he woke up in the morning, she could tell he knew something was up. His clothes had been packed. She’d already shown him photos of the Costa Mesa home and told him, “This is where you’re going. I’m still your mom. I’m still going to go and see you.”

Noah embraces his mother shortly before he was picked up and driven to a residential care facility in Costa Mesa.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

When the black SUV arrived, LyBurtus offered Oreos to coax him into the unfamiliar car. She followed the SUV in her car, staying far enough behind to avoid having Noah see her when he arrived. LyBurtus had been told it would ease the transition.

Back at home, she sank into the bathtub, utterly spent. “I’m going to have to just go with trusting this process as much as I can,” she said, “because I don’t have another choice right now.”

The next day, she met with the South STAR staff to tell them more about Noah. What he likes to eat. What triggers him. His favorite things to do. The Costa Mesa home called whenever staff had physically restrained Noah, but when a weekend passed without a call, she felt some relief.

Lyburtus smiled at the photos and videos sent home: putting together an elaborate stacking toy, washing dishes. It felt like things were going well, LyBurtus said. The staff had scaled back the amount of psychiatric medication he was taking.

But more than a month later, when she first went to visit Noah, he excitedly took her to the front door, as if to say, “Let’s go,” she recalled. She gently told him she was just visiting.

Christine LyBurtus is comforted by caregivers Schahara Zad, left, and Terrence Morris after Noah moved into his residential care facility.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

He led her to the side door instead. She steered him away again. They stepped into the courtyard, and Noah immediately went to the gate to exit.

LyBurtus fell into a funk. As she worried about Noah, she was also figuring out how to make ends meet. With Noah in the Costa Mesa home, Lyburtus was no longer being paid more than $4,000 a month as his caregiver, her sole source of income for years. She tried a number of jobs but ultimately found the work that suited her: caregiving for an elderly woman and children with disabilities.

Her second and third visits with Noah were easier. She snapped photos — Mother and son nestled together on the couch. Noah touching her forehead.

The STAR program runs up to 13 months. As time passed, the regional center had started talking to her about where Noah would go next. LyBurtus was startled.

Wasn’t the plan for him to come home, she asked?

Christine LyBurtus, left, is briefed by Kim Hamilton-Royse while touring a residential care facility for her son.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

That was still on the table, LyBurtus said she was told. But if he wasn’t ready, they didn’t want to wait until the last minute to find somewhere else for Noah, who turned 15 in May.

LyBurtus wanted to block out the idea of him going to another facility.

“I never want to live the way we were living again,” she said.

“But is that worse than him being hours away? I don’t know.”

Science

Owners of fire-destroyed Palisades mobile home park seek to displace residents for development deal

For months, former residents of the Pacific Palisades Bowl Mobile Estates have feared the uncommunicative owners of the property would seek to displace them in favor of a more lucrative development deal after the Palisades fire destroyed the rent-controlled, roughly 170-unit mobile home park.

A confidential memorandum listing the Bowl for sale indicates the owners intend to do exactly that.

The memorandum, quietly posted on a website associated with the global commercial real estate company CBRE, says that the Palisades fire created a “blank canvas for redevelopment” at a site “ideally positioned for a transformative residential or mixed-use project.”

“I just thought, oh my god, this is so much propaganda and false advertising,” said Lisa Ross, a 33-year resident of the Bowl and a Realtor. “How can they even get away with printing this?”

Neither the current owners of the Bowl nor the real estate companies listed on the memorandum responded to requests for comment.

The memorandum describes the current single-family residential zoning as “favorable” for developers; however, the city and mobile housing law experts have painted a different picture.

Fire debris at Pacific Palisades Bowl in January 2026.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“Multifamily and mixed-use development on this site is not allowed by existing zoning and land use regulations,” Mayor Karen Bass’s office said in a statement Wednesday, adding only low density single-family housing or reconstructing the mobile home park are currently allowed. “Mayor Bass will continue taking action and [work] with residents to restore the Palisades community.”

City Councilmember Traci Park also reiterated her focus on getting the mobile home park rebuilt and allowing residents to return, with a spokesperson noting she is not entertaining the potential for any rezoning efforts from a developer.

Zoning changes typically require a city council vote and are subject to the mayor’s approval or veto.

Beyond the zoning laws, the site is also currently governed by a state law requiring cities to preserve affordable housing along the coast and a city ordinance protecting mobile home residents against sudden displacement.

Spencer Pratt, a resident of the Palisades and an outspoken supporter of the neighborhood’s mobile home community, criticized the mayor and the owners in a statement to The Times. “It’s unfortunate that Karen Bass has not advocated for mobile home residents impacted by the fire,” he said, “and that the current owner of the Bowl is ignoring good faith offers from residents to buy the property.”

The mayor’s office disputed this, noting Bass recently led a delegation of Palisadians, including mobile home owners, to Sacramento to advocate for recovery. “Mayor Bass’ priority is getting every Palisadian home — single-family homeowners, town home owners, renters, mobile home owners.”

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass speaks during a private ceremony outside City Hall with faith leaders, LAPD officers and city officials to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Eaton and Palisades fires on Jan. 7, 2026.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Bass also advocated for the federal government to include the Bowl in its debris cleanup efforts; however, the Federal Emergency Management Agency ultimately refused to include it, unlike other mobile home parks impacted by the Palisades fire. Its reasoning: It could not trust the owners to rebuild the park as affordable housing.

Court rulings over the years found the owners routinely failed to maintain the infrastructure and worked to replace the park with an “upscale resort community.” Residents also accused the owners of attempting to circumvent rent control regulations.

After the fire, it ultimately took more than 13 months to begin cleaning up the debris.

Ross said she approached the owners with independent mobile home park developers who were interested in buying the fire-destroyed lot and letting residents rebuild within months. She also approached the owners with a proposition that the former residents band together to buy the park. She heard nothing back.

“They don’t communicate,” Ross said. “It’s a feuding family. That’s also why we had so many problems with maintenance and with upgrades in the park.”

Pratt, who is running for mayor against Bass, also called on private developers like Rick Caruso to step in and save the Bowl. (Caruso’s team noted his rebuilding nonprofit is looking into how to help residents of the Bowl.)

Ross is a fan of Pratt’s proposition. “We need those kinds of people — we need Rick Caruso. That would be great,” Ross said. To sweeten the deal: “I’ll cook for him. I would make him all his favorite dishes.”

Science

A virus without a vaccine or treatment is hitting California. What you need to know

A respiratory virus that doesn’t have a vaccine or a specific treatment regimen is spreading in some parts of California — but there’s no need to sound the alarm just yet, public health officials say.

A majority of Northern California communities have seen high concentrations of human metapneumovirus, or HMPV, detected in their wastewater, according to data from the WastewaterScan Dashboard, a public database that monitors sewage to track the presence of infectious diseases.

A Los Angeles Times data analysis found the communities of Merced in the San Joaquin Valley, and Novato and Sunnyvale in the San Francisco Bay Area have seen increases in HMPV levels in their wastewater between mid-December and the end of February.

HMPV has also been detected in L.A. County, though at levels considered low to moderate at this point, data show.

While HMPV may not necessarily ring a bell, it isn’t a new virus. Its typical pattern of seasonal spread was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, and its resurgence could signal a return to a more typical pre-coronavirus respiratory disease landscape.

Here’s what you need to know.

What is HMPV?

HMPV was first detected in 2001, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s transmitted by close contact with someone who is infected or by touching a contaminated surface, said Dr. Neha Nanda, chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist for Keck Medicine of USC.

Like other respiratory illnesses, such as influenza, HMPV spreads and is more durable in colder temperatures, infectious-disease experts say.

Human metapneumovirus cases commonly start showing up in January before peaking in March or April and then tailing off in June, said Dr. Jessica August, chief of infectious diseases at Kaiser Permanente Santa Rosa.

However, as was the case with many respiratory viruses, COVID disrupted that seasonal trend.

Why are we talking about HMPV now?

Before the pandemic hit in 2020, Americans were regularly exposed to seasonal viruses like HMPV and developed a degree of natural immunity, August said.

That protection waned during the pandemic, as people stayed home or kept their distance from others. So when people resumed normal activities, they were more vulnerable to the virus. Unlike other viruses, there isn’t a vaccine for human metapneumovirus.

“That’s why after the pandemic we saw record-breaking childhood viral illnesses because we lacked the usual immunity that we had, just from lack of exposure,” August said. “All of that also led to longer viral seasons, more severe illness. But all of these things have settled down in many respects.”

In 2024, the national test positivity for HMPV peaked at 11.7% at the end of March, according to the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System. The following year’s peak was 7.15% in late April.

So far this year, the highest test positivity rate documented was 6.1%, reported on Feb. 21 — the most recent date for which complete data are available.

While the seasonal spread of viruses like HMPV is nothing new, people became more aware of infectious diseases and how to prevent them during the pandemic, and they’ve remained part of the public consciousness in the years since, August and Nanda said.

What are the symptoms of HMPV?

Most people won’t go to the doctor if they have HMPV because it typically causes mild, cold-like symptoms that include cough, fever, nasal congestion and sore throat.

HMPV infection can progress to:

- An asthma attack and reactive airway disease (wheezing and difficulty breathing)

- Middle ear infections behind the ear drum

- Croup, also known as “barking” cough — an infection of the vocal cords, windpipe and sometimes the larger airways in the lungs

- Bronchitis

- Fever

Anyone can contract human metapneumovirus, but those who are immunocompromised or have other underlying medical conditions are at particular risk of developing severe disease — including pneumonia. Young children and older adults are also considered higher-risk groups, Nanda said.

What is the treatment for HMPV?

There is no specified treatment protocol or antiviral medication for HMPV. However, it’s common for an infection to clear up on its own and treatment is mostly geared toward soothing symptoms, according to the American Lung Assn.

A doctor will likely send you home and tell you to rest and drink plenty of fluids, Nanda said.

If symptoms worsen, experts say you should contact your healthcare provider.

How to avoid contracting HMPV

Infectious-disease experts said the best way to avoid contracting HMPV is similar to preventing other respiratory illnesses.

The American Lung Assn.’s recommendations include:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water. If that’s not available, clean your hands with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

- Clean frequently touched surfaces.

- Crack open a window to improve air flow in crowded spaces.

- Avoid being around sick people if you can.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

Assistant data and graphics editor Vanessa Martínez contributed to this report.

Science

After rash of overdose deaths, L.A. banned sales of kratom. Some say they lost lifeline for pain and opioid withdrawal

Nearly four months ago, Los Angeles County banned the sale of kratom, as well as 7-OH, the synthetic version of the alkaloid that is its active ingredient. The idea was to put an end to what at the time seemed like a rash of overdose deaths related to the drug.

It’s too soon to tell whether kratom-related deaths have dissipated as a result — or, really, whether there was ever actually an epidemic to begin with. But many L.A. residents had become reliant on kratom as something of a panacea for debilitating pain and opioid withdrawal symptoms, and the new rules have made it harder for them to find what they say has been a lifesaving drug.

Robert Wallace started using kratom a few years ago for his knees. For decades he had been in pain, which he says stems from his days as a physical education teacher for the Glendale Unified School District between 1989 and 1998, when he and his students primarily exercised on asphalt.

In 2004, he had arthroscopic surgery on his right knee, followed by varicose vein surgery on both legs. Over the next couple of decades, he saw pain-management specialists regularly. But the primary outcome was a growing dependence on opioid-based painkillers. “I found myself seeking doctors who would prescribe it,” he said.

He leaned on opioids when he could get them and alcohol when he couldn’t, resulting in a strain on his marriage.

When Wallace was scheduled for his first knee replacement in 2021 (he had his other knee replaced a few years later), his brother recommended he take kratom for the post-surgery pain.

It seemed to work: Wallace said he takes a quarter of a teaspoon of powdered kratom twice a day, and it lets him take charge of managing his pain without prescription painkillers and eases harsh opiate-withdrawal symptoms.

He’s one of many Angelenos frustrated by recent efforts by the county health department to limit access to the drug. “Kratom has impacted my life in only positive ways,” Wallace told The Times.

For now, Wallace is still able to get his kratom powder, called Red Bali, by ordering from a company in Florida.

However, advocates say that the county crackdown on kratom could significantly affect the ability of many Angelenos to access what they say is an affordable, safer alternative to prescription painkillers.

Kratom comes from the leaves of a tree native to Southeast Asia called Mitragyna speciosa. It has been used for hundreds of years to treat chronic pain, coughing and diarrhea as well as to boost energy — in low doses, kratom appears to act as a stimulant, though in higher doses, it can have effects more like opioids.

Though advocates note that kratom has been used in the U.S. for more than 50 years for all sorts of health applications, there is limited research that suggests kratom could have therapeutic value, and there is no scientific consensus.

Then there’s 7-OH, or 7-Hydroxymitragynine, a synthetic alkaloid derived from kratom that has similar effects and has been on the U.S. market for only about three years. However, because of its ability to bind to opioid receptors in the body, it has a higher potential for abuse than kratom.

Public health officials and advocates are divided on kratom. Some say it should be heavily regulated — and 7-OH banned altogether — while others say both should be accessible, as long as there are age limitations and proper labeling, such as with alcohol or cannabis.

In the U.S., kratom and 7-OH can be found in all sorts of forms, including powder, capsules and liquids — though it depends on exactly where you are in the country. Though the Food and Drug Administration has recommended that 7-OH be included as a Schedule 1 controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act, that hasn’t been made official. And the plant itself remains unscheduled on the federal level.

That has left states, counties and cities to decide how to regulate the substances.

California failed to approve an Assembly bill in 2024 that would have required kratom products to be registered with the state, have labeling and warnings, and be prohibited from being sold to anyone younger than 21.

It would also have banned products containing synthetic versions of kratom alkaloids. The state Legislature is now considering another bill that basically does the same without banning 7-OH — while also limiting the amount of synthetic alkaloids in kratom and 7-OH products sold in the state.

“Until kratom and its pharmacologically active key ingredients mitragynine and 7-OH are approved for use, they will remain classified as adulterants in drugs, dietary supplements and foods,” a California Department of Public Health spokesperson previously told The Times.

On Tuesday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state’s efforts to crack down on kratom products has resulted in the removal of more than 3,300 kratom and 7-OH products from retail stores. According to a news release from the governor’s office, there has been a 95% compliance rate from businesses in removing the products.

(Los Angeles Times photo illustration; source photos by Getty Images)

Newsom has equated these actions to the state’s efforts in 2024 to quash the sale of hemp products containing cannabinoids such as THC. Under emergency state regulations two years ago, California banned these specific hemp products and agents with the state Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control seized thousands of products statewide.

Since the beginning of 2026, there have been no reported violations of the ban on sales of such products.

“We’ve shown with illegal hemp products that when the state sets clear expectations and partners with businesses, compliance follows,” Newsom said in a statement. “This effort builds on that model — education first, enforcement where necessary — to protect Californians.”

Despite the state’s actions, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors is still considering whether to regulate kratom, or ban it altogether.

The county Public Health Department’s decision to ban the sale of kratom didn’t come out of nowhere. As Maral Farsi, deputy director of the California Department of Public Health, noted during a Feb. 18 state Senate hearing, the agency “identified 362 kratom-related overdose deaths in California between 2019 and 2023, with a steady increase from 38 in 2019 up to 92 in 2023.”

However, some experts say those numbers aren’t as clear-cut as they seem.

For example, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that in a number of recent L.A. County deaths that were initially thought to be caused by kratom or 7-OH, there wasn’t enough evidence to say those drugs alone caused the deaths; it might be the case that the danger is in mixing them with other substances.

Meanwhile, the actual application of this new policy seems to be piecemeal at best.

The county Public Health Department told The Times it conducted 2,696 kratom-related inspections between Nov. 10 and Jan. 27, and found 352 locations selling kratom products. The health department said the majority stopped selling kratom after those inspections; there were nine locations that ignored the warnings, and in those cases, inspectors impounded their kratom products.

But the reality is that people who need kratom will buy it on the black market, drive far enough so they get to where it’s sold legally or, like Wallace, order it online from a different state.

For now, retailers who sell kratom products are simply carrying on until they’re investigated by county health inspectors.

Ari Agalopol, a decorated pianist and piano teacher, saw her performances and classes abruptly come to a halt in 2012 after a car accident resulted in severe spinal and knee injuries.

“I tried my best to do traditional acupuncture, physical therapy and hydrocortisone shots in my spine and everything,” she said. “Finally, after nothing was working, I relegated myself to being a pain-management patient.”

She was prescribed oxycodone, and while on the medication, battled depression, anhedonia and suicidal ideation. She felt as though she were in a fog when taking oxycodone, and when it ran out, ”the pain would rear its ugly head.” Agalopol struggled to get out of bed daily and could manage teaching only five students a week.

Then, looking for alternatives to opioids, she found a Reddit thread in which people were talking up the benefits of kratom.

“I was kind of hesitant at first because there’re so many horror stories about 7-OH, but then I researched and I realized that the natural plant is not the same as 7-OH,” she said.

She went to a local shop, Authentic Kratom in Woodland Hills, and spoke to a sales associate who helped her decide which of the 47 strains of kratom it sold would best suit her needs.

Agalopol currently takes a 75-milligram dose of mitragynine, the primary alkaloid in kratom, when necessary. It has enabled her to get back to where she was before her injury: teaching 40 students a week and performing every weekend.

Agalopol believes the county hasn’t done its homework on kratom. “They’re just taking these actions because of public pressure, and public pressure is happening because of ignorance,” she said.

During the course of reporting this story, Authentic Kratom has shut down its three locations; it’s unclear if the closures are temporary. The owner of the business declined to comment on the matter.

When she heard the news of the recent closures, Agalopol was seething. She told The Times she has enough capsules of kratom for now, but when she runs out, her option will have to be Tylenol and ibuprofen, “which will slowly kill my liver.”

“Prohibition is not a public health strategy,” said Jackie Subeck, executive director of 7-Hope Alliance, a nonprofit that promotes safe and responsible access to 7-OH for consumers, at the Feb. 18 Senate hearing. “[It’s] only going to make things worse, likely resulting in an entirely new health crisis for Californians.”

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Wisconsin4 days ago

Wisconsin4 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Oregon7 days ago

Oregon7 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling