Science

For Patients Needing Transplants, Hope Arrives on Tiny Hooves

More than 100,000 Americans are on waiting lists for donor organs, most needing a kidney. Only 25,000 human donor kidneys become available each year. Twelve Americans on the kidney list die every day on average.

Scientists first transplanted genetically engineered pig organs into other animals and then to brain-dead human patients. In 2022, researchers received permission to transplant the organs into a few critically ill patients, and then, last year, into healthier people.

Now, for the first time, a formal clinical study of the procedure is being initiated.

“Just imagine, you have kidney disease and know your kidneys are going to fail, and you have a pig’s kidney waiting for you — and you never see dialysis,” said Mike Curtis, president and chief executive at eGenesis.

He foresees a future in which genetic engineering will make pig organs so compatible with humans that patients won’t have to take powerful drugs that prevent rejection but make them vulnerable to infections and cancer.

Babies born with serious heart defects might be given a pig’s heart temporarily while waiting for a human donor heart. A pig’s liver could potentially serve as a bridge for those in need of a human liver.

Some scientists argue that there is a moral imperative to move forward.

“Is it ethical to let thousands of people die each year on a waiting list when we have something that could possibly save their lives?” asked Dr. David K.C. Cooper, who studies xenotransplantation at Harvard and is a consultant to eGenesis.

“I think it’s beginning to be ethically unacceptable to let people die when there’s an alternative therapy that looks pretty encouraging.”

But critics say xenotransplantation is a hubristic, pie-in-the-sky endeavor aiming to solve an organ shortage with technology when there’s a simpler solution: expanding the supply of human organs by encouraging more donation.

And xenotransplantation is freighted with unanswered questions.

Pigs can carry pathogens that can find their way to humans. If a deadly virus, for example, were to emerge in transplant patients, it could spread with catastrophic consequences.

It might be years or even decades before symptoms were observed, warned Christopher Bobier, a bioethicist from the Central Michigan University College of Medicine.

“A potential zoonotic transference could happen at any point after a transplant — in perpetuity,” he said. The risk is believed to be small, he added, “but it is not zero.”

Science

When slowing down can save a life: Training L.A. law enforcement to understand autism

Kate Movius moved among a roomful of Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies, passing out a pop trivia quiz and paper prism glasses.

She told them to put on the vision-distorting glasses, and to write with their nondominant hand. As they filled out the tests, Movius moved about the City of Industry classroom pounding abruptly on tables. Then came the cowbell. An aide flashed the overhead lights on and off at random. The goal was to help the deputies understand the feeling of sensory overwhelm, which many autistic people experience when incoming stimulation exceeds their capacity to process.

“So what can you do to assist somebody, or de-escalate somebody, or get information from someone who suffers from a sensory disorder?” Movius asked the rattled crowd afterward. “We can minimize sensory input. … That might be the difference between them being able to stay calm and them taking off.”

Movius, founder of the consultancy Autism Interaction Solutions, is one of a growing number of people around the U.S. working to teach law enforcement agencies to recognize autistic behaviors and ensure that encounters between neurodevelopmentally disabled people and law enforcement end safely.

She and City of Industry Mayor Cory Moss later passed out bags filled with tools donated by the city to aid interactions: a pair of noise-damping headphones to decrease auditory input, a whiteboard, a set of communication cards with words and images to point to, fidget toys to calm and distract.

“The thing about autistic behavior when it comes to law enforcement is a lot of it may look suspicious, and a lot of it may feel very disrespectful,” said Movius, who is also the parent of an autistic 25-year-old man. Responding officers, she said, “are not coming in thinking, ‘Could this be a developmentally disabled person?’ I would love for them to have that in the back of their minds.”

A sheriff’s deputy reads a pamphlet on autism during the training program.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Autism spectrum disorder is a developmental condition that manifests differently in nearly every person who has it. Symptoms cluster around difficulties in communication, social interaction and sensory processing.

An autistic person stopped by police might hold the officer’s gaze intensely or not look at them at all. They may repeat a phrase from a movie, repeat the officer’s question or temporarily lose their ability to speak. They might flee.

All are common involuntary responses for an autistic person in a stressful situation, which a sudden encounter with law enforcement almost invariably is. To someone unfamiliar with the condition, all could be mistaken for intoxication, defiance or guilt.

Autism rates in the U.S. have increased nearly fivefold since the Centers for Disease Control began tracking diagnoses in 2000, a rise experts attribute to broadening diagnostic criteria and better efforts to identify children who have the condition.

The CDC now estimates that 1 in 31 U.S. 8-year-olds is autistic. In California, the rate is closer to 1 in 22 children.

As diverse as the autistic population is, people across the spectrum are more likely to be stopped by law enforcement than neurotypical peers.

About 15% of all people in the U.S. ages 18 to 24 have been stopped by police at some point in their lives, according to federal data. While the government doesn’t track encounters for disabled people specifically, a separate study found that 20% of autistic people ages 21 to 25 have been stopped, often after a report or officer observation of a person behaving unusually.

Some of these encounters have ended in tragedy.

In 2021, Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies shot and permanently paralyzed a deaf autistic man after family members called 911 for help getting him to a hospital.

Isaias Cervantes, 25, had become distressed about a shopping trip and started pushing his mother, his family’s attorney said at the time. He resisted as two deputies attempted to handcuff him and one of the deputies shot him, according to a county report.

In 2024, Ryan Gainer’s family called 911 for support when the 15-year-old became agitated. Responding San Bernardino County sheriff‘s deputies shot and killed him outside his Apple Valley home.

Last year, police in Pocatello, Idaho, shot Victor Perez, 17, through a chain-link fence after the nonspeaking teenager did not heed their shouted commands. He died from his injuries in April.

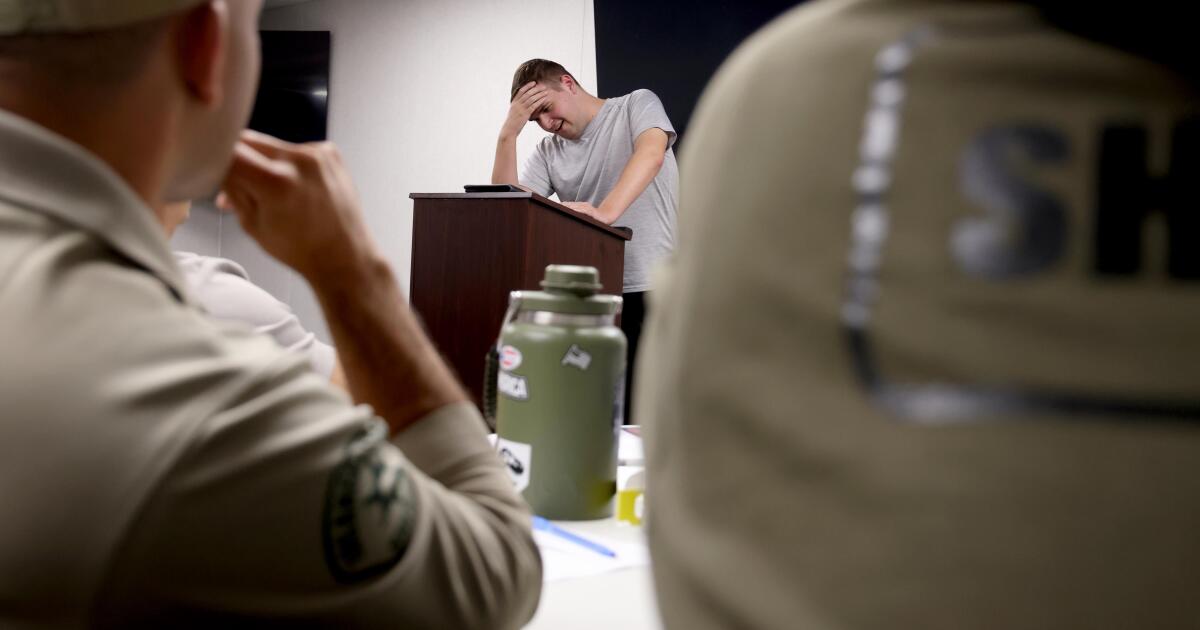

Sheriff’s deputies take a trivia quiz using their non-writing hands, while wearing vision-distorting glasses, as Kate Movius, standing left, and Industry Mayor Cory Moss, right, ring cowbells. The idea was to help them understand the sensory overwhelm some autistic people experience.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

As early as 2001, the FBI published a bulletin on police officers’ need to adjust their approach when interacting with autistic people.

“Officers should not interpret an autistic individual’s failure to respond to orders or questions as a lack of cooperation or as a reason for increased force,” the bulletin stated. “They also need to recognize that individuals with autism often confess to crimes that they did not commit or may respond to the last choice in a sequence presented in a question.”

But a review of multiple studies last year by Chapman University researchers found that while up to 60% of officers have been on a call involving an autistic person, only 5% to 40% had received any training on autism.

In response, universities, nonprofits and private consultants across the U.S. have developed curricula for law enforcement on how to recognize autistic behaviors and adapt accordingly.

The primary goal, Movius told deputies at November’s training session, is to slow interactions down to the greatest extent possible. Many autistic people require additional time to process auditory input and verbal responses, particularly in unfamiliar circumstances.

If at all possible, Movius said, wait 20 seconds for a response after asking a question. It may feel unnaturally long, she acknowledged. But every additional question or instruction fired in that time — what’s your name? Did you hear me? Look at me. What’s your name? — just decreases the likelihood that a person struggling to process will be able to respond at all.

Moss’ son, Brayden, then 17, was one of several teenagers and young adults with autism who spoke or wrote statements to be read to the deputies. The diversity of their speech patterns and physical mannerisms showed the breadth of the spectrum. Some were fluently verbal, while others communicated through signs and notes.

“This population is so diverse. It is so complicated. But if there’s anything that we can show [deputies] in here that will make them stop and think, ‘Hey, what if this is autism?’ … it is saving lives,” Moss said.

Mayor Cory Moss, left, and Kate Movius hug at the end of the training program last November. Movius started Autism Interaction Solutions after her son was born with profound autism.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Some disability advocates cautioned that it takes more than isolated training sessions to ensure encounters end safely.

Judy Mark, co-founder and president of the nonprofit Disability Voices United, says she trained thousands of officers on safe autism interactions but stopped after Cervantes’ shooting. She now urges families concerned about an autistic child’s safety to call an ambulance rather than law enforcement.

“I have significant concern about these training sessions,” Mark said. “People get comfort from it, and the Sheriff’s Department can check the box.”

While not a panacea, supporters argue that a brief course is better than no preparation at all. Some years ago, Movius received a letter from a man whose profoundly autistic son slipped away as the family loaded their car at the beach. He opened the unlocked door of a police vehicle, climbed into the back and began to flail in distress.

Though surprised, the officer seated at the wheel de-escalated the situation and helped the young man find his family, the father wrote to Movius. He had just been to her training.

Science

Bodies of all 9 skiers killed in devastating avalanche recovered by authorities

California search-and-rescue teams have recovered the bodies of all nine missing skiers killed Tuesday in a devastating avalanche in a remote region of Sierra Nevada north of Lake Tahoe.

When a catastrophic avalanche rumbled over a stretch of the High Sierra, dozens of law enforcement officers scoured the mountainside for a group of 15 skiers, including four mountain guides.

Within hours, crews rescued six survivors and discovered eight deceased skiers near the Frog Lake Backcountry Huts. Another skier was still missing, but was presumed dead.

After five days of navigating deep snowpack and treacherous weather conditions, authorities announced they had found the body of the ninth victim.

During a press conference on Saturday afternoon, Nevada County identified the victims as six skiers and three professional mountain guides:

- Andrew Alissandratos, 34, of Verdi, Nev., a Blackbird Mountain Guide

- Carrie Atkin, 46, of Soda Springs, Calif.

- Nicole Choo, 42, of South Lake Tahoe, Calif., Blackbird Mountain Guide

- Lizabeth Clabaugh, 52, of Boise, Idaho

- Michael Henry, 30, from Soda Springs, Calif., a Blackbird Mountain Guide

- Danielle Keatley, 44, of Soda Springs and Larkspur, Calif.

- Kate Morse, 45, of Soda Springs and Tiburon, Calif.

- Caroline Sekar, 45, of Soda Springs and San Francisco, Calif.

- Katherine Vitt, 43, of Greenbrae, Calif.

Authorities lamented the fast-moving disaster as the deadliest avalanche in modern California history.

“There are no words that truly capture the significance of this loss and our hearts mourn alongside the families of those affected by this catastrophic event,” Nevada County Sheriff Shannan Moon said in a statement on Saturday. “The weight of this event is felt across many families, friends, and colleagues, and we stand together with them during this difficult time.” Moon said.

The avalanche occurred amid a powerful atmospheric river storm that unleashed several feet of snow onto the Sierra Nevada mountains. First responders maneuvered through the blizzard on snowcats and skis to rescue the survivors.

But the unstable snowpack, high winds and whiteout conditions made search-and-recovery efforts too perilous, prompting first responders to leave behind the bodies of deceased skiers and suspend operations on Wednesday and Thursday.

Authorities carved paths through the deep snow to eventually continue the search, and California Highway Patrol officers found the ninth victim.

The Nevada County Sheriff‘s Office was also assisted by California National Guard, California State Parks, Placer County Sheriff’s Office, Washoe County Sheriff’s Office, California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, Truckee Police Department and the United States Forest Service.

Science

Video: ‘Very Successful Day’: NASA Completes Artemis II Launchpad Test

new video loaded: ‘Very Successful Day’: NASA Completes Artemis II Launchpad Test

transcript

transcript

‘Very Successful Day’: NASA Completes Artemis II Launchpad Test

NASA successfully completed a rehearsal to launch the Artemis II rocket on Thursday. The mission would send astronauts around the Moon’s orbit for the first time in more than 50 years.

-

“Very successful day. I’m very proud of this team and all that they accomplished to get us to yesterday, and then to go execute with such precision.” “Following that successful wet dress yesterday, we’re now targeting March 6 as our earliest launch attempt. I am going to caveat that — I want to be open, transparent with all of you, that there is still pending work.”

By Jorge Mitssunaga

February 20, 2026

-

Montana4 days ago

Montana4 days ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma6 days ago

Oklahoma6 days agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Secret New York City Passage Linked to Underground Railroad

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoChicago-area teacher breaks silence after losing job over 2-word Facebook post supporting ICE: ‘Devastating’

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoWorld reacts as US top court limits Trump’s tariff powers

-

Politics3 days ago

Politics3 days agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT