Science

Column: He was the oldest man in the U.S., and his loving caretaker was with him to the end

The oldest male in the United States was a man of many appetites, even at 110, and his live-in caretaker did her best to feed them.

Rosario Reyes would make banana pancakes for Morrie Markoff, and he would plead for more syrup. She’d bring him a corned beef sandwich, followed by a piece of lemon meringue pie, and reluctantly give in when he insisted on washing that down with a cup of hot chocolate.

Markoff wanted to read the paper, watch the news and get in some exercise every day, and Reyes helped make it happen. He made clear that on his 111th birthday in January, he fully expected an exotic dancer to perform in the living room of his Bunker Hill apartment, for the third straight year. Reyes already had the balloons in storage.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

In their normal daily routine, they’d listen to classical music together or watch, yet again, two of Markoff’s favorite movies: “Midway” or “Guns of Navarone.” Markoff also liked “The Notebook,” which Reyes hadn’t seen. He bet her that if they watched it together, she would cry. And she did.

He called her by her nickname, Charito. She called him Mr. Morrie.

“It was kind of a remarkable relationship,” said Judith Hansen, Markoff’s daughter, who called Reyes an angel and one of countless unsung heroes in the elder-care ranks. “Dad would not have lived as long as he did without Charito. She’s an incredibly wise woman, and she knew what would keep him going. She knew that he was a man who wanted to accomplish something each day.”

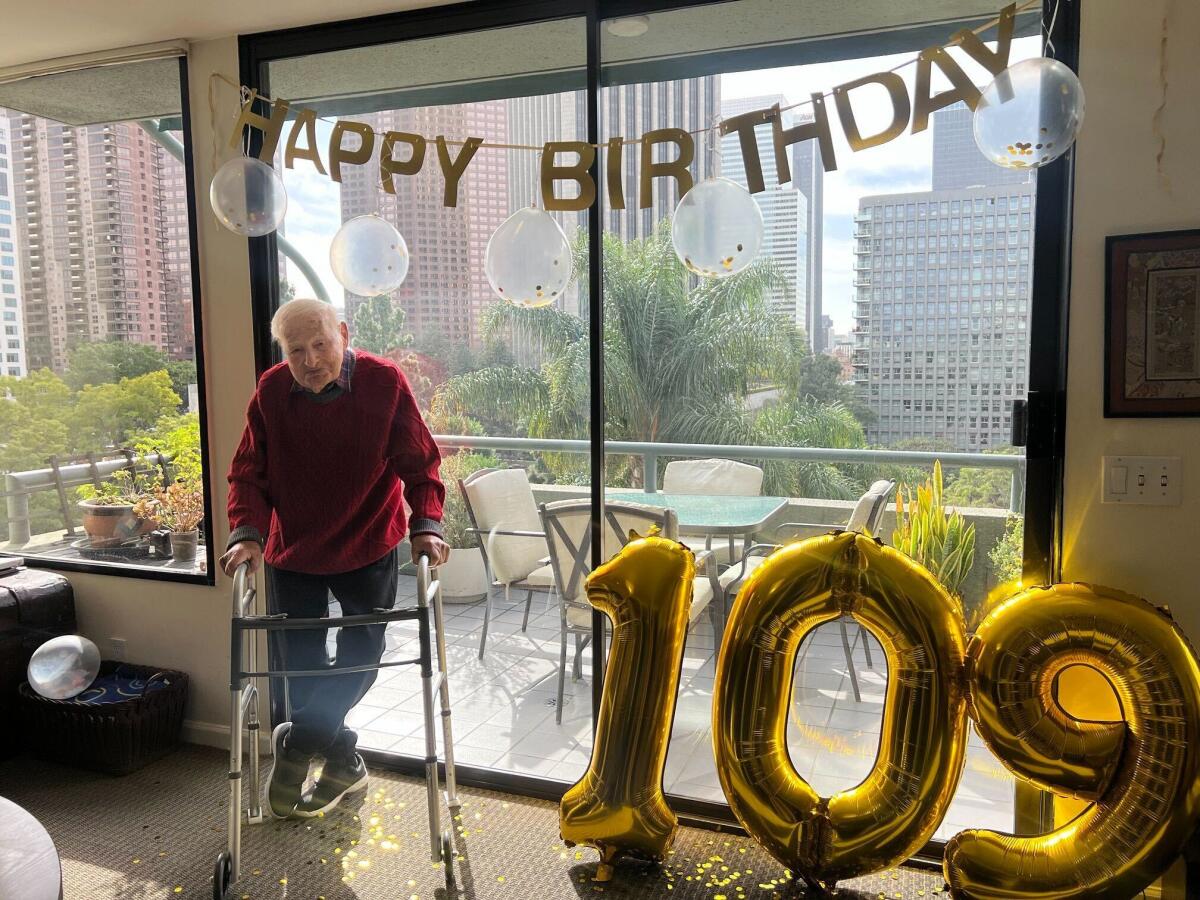

Markoff celebrated his 109th birthday in downtown Los Angeles.

(Family photo)

And he usually did, until his body began giving out in April. Markoff was briefly hospitalized a few weeks ago and died at home June 3, with Charito holding Mr. Morrie’s hands in hers.

“He died in peace,” she said.

I was lucky to have met Markoff when he responded to a 2012 column I wrote about having been resuscitated after going into cardiac arrest following knee replacement surgery. He’d been a goner, too, Markoff said, just shy of his 99th birthday, and we ought to have a cup of coffee and “hang around” together as full-fledged members of the Back From the Dead Club.

Markoff grew up in a New York City tenement, dropped out of school after eighth grade, went to a trade school, married his beloved Betty in 1938 and moved west, where he sometimes drove her crazy with his manic energy and argumentative nature. As he aged and mellowed, Markoff swooned over his beloved “Betsy,” as he called her, and after she died in 2019, he couldn’t stop singing a song he wrote about pining to be with her again.

I had the pleasure of being at Markoff’s 100th birthday party (there was cake, but no exotic dancers), Betty’s 100th and their 75th wedding anniversary. He once said to me that he couldn’t recall being bored a day in his life, and that was his gift to all of us: the reminder that if you stay plugged into the world around you and open yourself to new experiences, the aging process can slow to a crawl.

“If I had to put my finger on one thing that helped his longevity, I would say it was his innate curiosity about everything,” said his son, Steven, who, like his sister, is in his 80s.

That and, of course, the luck of good genes.

Markoff and his wife, Betty, at home in September 2013.

(Los Angeles Times)

“You could bring him a sow bug,” Steven said, “and he would say, ‘Look, it rolled into a little ball. How did it do that?’ Or he would say, ‘I just met the most interesting person in the world on a bus.’”

In fact, Morrie and Betty loved exploring Los Angeles by bus, and one day they met Tracy Huston, the owner of a Chinatown gallery. Markoff, who was trained as a machinist but held a variety of jobs, mentioned that while servicing and repairing gadgets and appliances, he’d noticed that a toilet tank float looked like the skirt of a ballerina. So he began welding scrap metal parts together, fashioning dozens of sculptures, including a ballerina.

Huston was intrigued, and in 2014, I attended Markoff’s first-ever art exhibit, in her gallery. It was yet another high point in a life that had just hit the century mark, and one of my most prized possessions — a gift from Markoff — is his sculpture of his daughter reading a book.

I once visited the Markoffs with the late Times photographer Gary Friedman, who adored them. When Markoff mentioned that he’d taken thousands of black-and-white photographs on his world travels, Friedman was astonished by the quality of the work in Markoff’s neatly archived albums and told him they ought to be in a museum.

Markoff frequently talked to me about his years-in-the-making memoir, and the working title was his answer to a question he fielded often: “What is the secret to a long life?” Markoff was 103 when he sold copies of “Keep Breathing” from his very own booth at the L.A. Times Festival of Books.

When I wrote about attending his 109th birthday party last year, I noted that Markoff’s live-in care was a luxury many people won’t be able to afford, given longer lifespans. He’d saved and invested well, Steven told me at the time, but the cost of 24-hour care can easily run $10,000-$15,000 monthly, and the shortage of home healthcare workers is a massive unaddressed challenge.

“The real lesson learned from this is how unprepared our government is to deal with end of life for people,” Steven told me the other day. “It seems to me a tragedy, with all the money that’s spent in other ways.”

When Markoff was nearing the end, Judith got the idea that with so many millions of people experiencing dementia in old age, her father’s extraordinary brain might be useful to researchers. She went to the National Institutes of Health website and was linked to Tish Hevel of the nonprofit Brain Donor Project, who gladly accepted the donation.

“Lots of studies are being done on super-agers, and he may be the super-est of super-agers,” Hevel told me. “Some people in brain banking think this could be the oldest cognitively intact brain that is now preserved.”

Hevel said 16,000 brains are in the bank, helping researchers study mental illness, Parkinson’s disease, cognitive loss and other neurological disorders. Having a healthy brain like Markoff’s can be invaluable, Hevel said, for comparative analysis.

“I think Dad would be tickled to death to know that someone was interested enough to analyze his brain,” said Steven, who had lunch with his father weekly and was struck by how sharp he remained until several weeks ago, when he began to fade and the family decided to begin hospice care.

Reyes, who has a daughter in college, met the Markoffs about 20 years ago, when she worked as their housekeeper. It was only in the last few years that the native of Peru became Markoff’s full-time caregiver. When I met with her Saturday morning at Markoff’s apartment, she shared a packet of handwritten notes he’d written to me but hadn’t yet mailed.

“With all the young people being killed in fruitless wars,” he wrote in one, using cursive on lined paper, “the undertakers don’t need me. They are busy enough.”

He was a lifelong progressive, and Reyes said he told her he had lived through many of the world’s miseries, including the Spanish flu and COVID-19 pandemics, two world wars and the death of civil discourse over the last several years.

“This was always his favorite place,” Reyes said, showing me the sunroom from which Markoff would take in the view of downtown L.A. high-rises.

He was like the Energizer bunny, she said, in a hurry to drag out the trash bins or head out for a brisk walk. She said she had to hustle to keep him busy, so each day, on a legal pad, she wrote a list of things for Markoff to do, including read the paper, exercise, play cards, watch the evening news, reach out to family and work on his blog (he billed himself as the world’s oldest blogger).

“Always make a plan,” she recalled him saying on many occasions. “Never stop. Next. Next. Next.”

Markoff celebrated his 108th birthday with his daughter-in-law, Jadwiga.

(Steve Lopez / Los Angeles Times)

She showed me a video she took of Markoff watching news of the solar eclipse in April.

“I’m a lucky man,” he said. “It’s wonderful to sit here in comfort and watch the eclipse happen.”

In Markoff’s final hours, Reyes told him he was going to be with Betty again. It was the saddest moment of her life, she told me, but knowing Markoff wouldn’t want to go on living if he couldn’t keep moving, keep discovering, keep making plans, she told him he would be better off.

His color changed at the moment of his death, Reyes said, and she told him to reach for Betty’s hand.

“He died in peace,” Reyes said. “And he’s where he wants to be.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

Science

Q&A: Learn how Olympians keep their cool from Team USA's chief sports psychologist

Your morning jog or weekly basketball game may not take place on an Olympic stage, but you can use Team USA’s techniques to get the most out of your exercise routine.

It’s not all about strength and speed. Mental fitness can be just as important as physical fitness.

That’s why the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee created a psychological services squad to support the mental health and mental performance of athletes representing the Stars and Stripes.

“I think happy, healthy athletes are going to perform at their best, so that’s what we’re striving for,” said Jessica Bartley, senior director of the 15-member unit.

Bartley studied sports psychology and mental health after an injury ended her soccer career. She joined the USOPC in 2020 and is now in Paris with Team USA’s 592 competitors, who range in age from 16 to 59.

Bartley spoke with The Times about how her crew keeps Olympic athletes in top psychological shape, and what the rest of us can learn from them. Her comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Why is exercise good for mental health?

It gets you moving. It gets the endorphins going. And there’s often a lot of social aspects that are really helpful.

There are a number of sports that stretch your brain in ways that can be really, really valuable. You’re thinking about hand-eye coordination, or you’re thinking about strategy. It can improve memory, concentration, even critical thinking.

What’s the best way to get in the zone when it’s time to compete?

When I work with athletes, I like to understand what their zone is. If a 0 or a 1 is you’re totally chilled out and a 10 is you’re jumping around, where do you need to be? What’s your number?

People will say, “I’m at a 10 and I need to be at an 8 or a 7.” So we’ll talk about ways of bringing it down, whether it’s taking a deep breath, listening to relaxing music, or talking to your coach. Or there’s times when people say they need to be more amped up. That’s when you see somebody hitting their chest, or jumping up and down.

If you make a mistake in the middle of a competition, how do you move on instead of dwelling on it?

I often teach athletes a reset routine. I played goalie, so I had a lot of time to think after getting scored on. I would undo my goalie gloves and put them back on, which to me was a reset. I would also wear an extra hairband on my wrist, and when I would snap it, that meant I needed to get out of my head.

It’s not just a physical reset — it helps with a mental reset. If you do the same thing every single time, it goes through the same neural pathway to where it’s going to reset the brain. That can be really impactful.

Do Olympic athletes have to deal with burnout?

Oh, yeah. Everybody has a day where they don’t want to do whatever it is. That’s when you have to ask, “What’s in my best interests? Do I need a recovery day, or do I really need to get in the pool, or get in the gym?”

Sometimes you really do need what we like to refer to as a mental health day.

How can you psych yourself up for a workout when you just aren’t feeling it?

It’s really helpful to think about why you’re doing this and why you’re pushing yourself. Do you have goals related to an activity or sport? Is there something tied to values around hard work or discipline, loyalty or dependability?

When you don’t want to get in the gym, when you don’t want to go for a run, think about something bigger. Tie it back to values.

Is sleep important for maintaining mental health?

Yes! We started doing mental health screens with athletes before the Tokyo Games. We asked about depression, anxiety, disordered eating and body image, drugs and alcohol, and sleep. Sleep was actually our No. 1 issue. It’s been a huge initiative for us.

How much sleep should we be getting?

It’s different for everyone, but generally we know seven to nine hours of sleep is good. Sometimes some of these athletes need 10 hours.

I highly recommend as much sleep as you need. If you didn’t get enough sleep, napping can be really valuable.

Is napping just for Olympic athletes or is it good for everybody?

Everybody! Naps are amazing.

What if there’s no time for a nap?

There are different ways of recharging. Naps could be one of them, but maybe you just need to get off your feet for 20 minutes. Maybe you need to do a meditation or mindfulness exercise and just close your eyes for five minutes.

How do you minimize the effects of jet lag?

We try to shift one hour per day. That’s the standard way of doing it. If you can, it’s super helpful. But it’s not always possible.

The thing we tell athletes is that our bodies are incredible, and you will even things out if you can get back on schedule. One or two nights of crummy sleep is not going to impact your overall performance.

What advice do you give athletes who have trouble falling asleep the night before a competition?

You don’t want to change much right before a competition, so I usually direct athletes to do what they would normally do.

Do you need to unwind by reading a book? Do you need to talk on the phone with somebody and get your mind off things? Can you put your mind in a really restful place and think about things that are really relaxing?

Are there any mindfulness or meditation exercises that you find helpful?

There are some athletes who benefit greatly from an hourlong meditation. I love something quick, something to reset my brain, maybe close my eyes for a minute.

If I’m feeling like I need to take a moment, I love mindful eating. You savor a bite and go, “Oh, my gosh, I have not been fully engaged with my senses today.” Or you could take a mindful walk and take in the sights, the smells, all of the things that are around you.

What do you eat when you need a quick nutrition boost?

Cashews. I tend to carry those with me. They’ve got enough energy to make sure I keep going, physically.

I’ve always got gummy bears on me too. There’s no nutritional value but they keep me going mentally. I’m a big proponent of both.

Is it OK to be superstitious in sports?

It depends how flexible you are. Maybe you put on your socks or shoes a certain way, or listen to certain music. Routines are really soothing. They set your brain up for success in a particular performance. It can be really, really helpful.

But I’ve also seen an athlete forget their lucky underwear or their lucky socks, and they’re all out of sorts. So your routine has to be flexible enough that you’re not going to completely fall apart if you don’t do it exactly.

Are Olympians made of stronger psychological stuff than the rest of us?

Not necessarily. There are some who don’t get feathers ruffled and have a high tolerance for the fanfare. There’s also a lot of regular human beings who just happen to be fantastic at a particular activity.

Science

‘Ready, Steady, Slow’: Championship Snail Racing at 0.006 M.P.H.

Earlier this month, the rural village of Congham, England, played host to a less likely group of athletes: dozens of garden snails. They had gathered to compete in the World Snail Racing Championships, where the world record time for completing the 13.5 inch course stands at 2 minutes flat. At that speed — roughly 0.006 miles per hour — it would take the snails more than six days to travel a mile.

Science

Caring for condor triplets! Record 17 chicks thrive at L.A. Zoo under surrogacy method

A new method of rearing California condors at the Los Angeles Zoo has resulted in a record-breaking 17 chicks hatched this year, the zoo announced Wednesday.

All of the newborn birds will eventually be considered for release into the wild under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s California Condor Recovery Program, a zoo spokesperson said.

“What we are seeing now are the benefits of new breeding and rearing techniques developed and implemented by our team,” zoo bird curator Rose Legato said in a statement. “The result is more condor chicks in the program and ultimately more condors in the wild.”

Breeding pairs of California condors live at the zoo in structures the staff “affectionately calls condor-miniums,” spokesperson Carl Myers said. When a female produces a fertilized egg, the egg is moved to an incubator. As its hatching approaches, the egg is placed with a surrogate parent capable of rearing the chick.

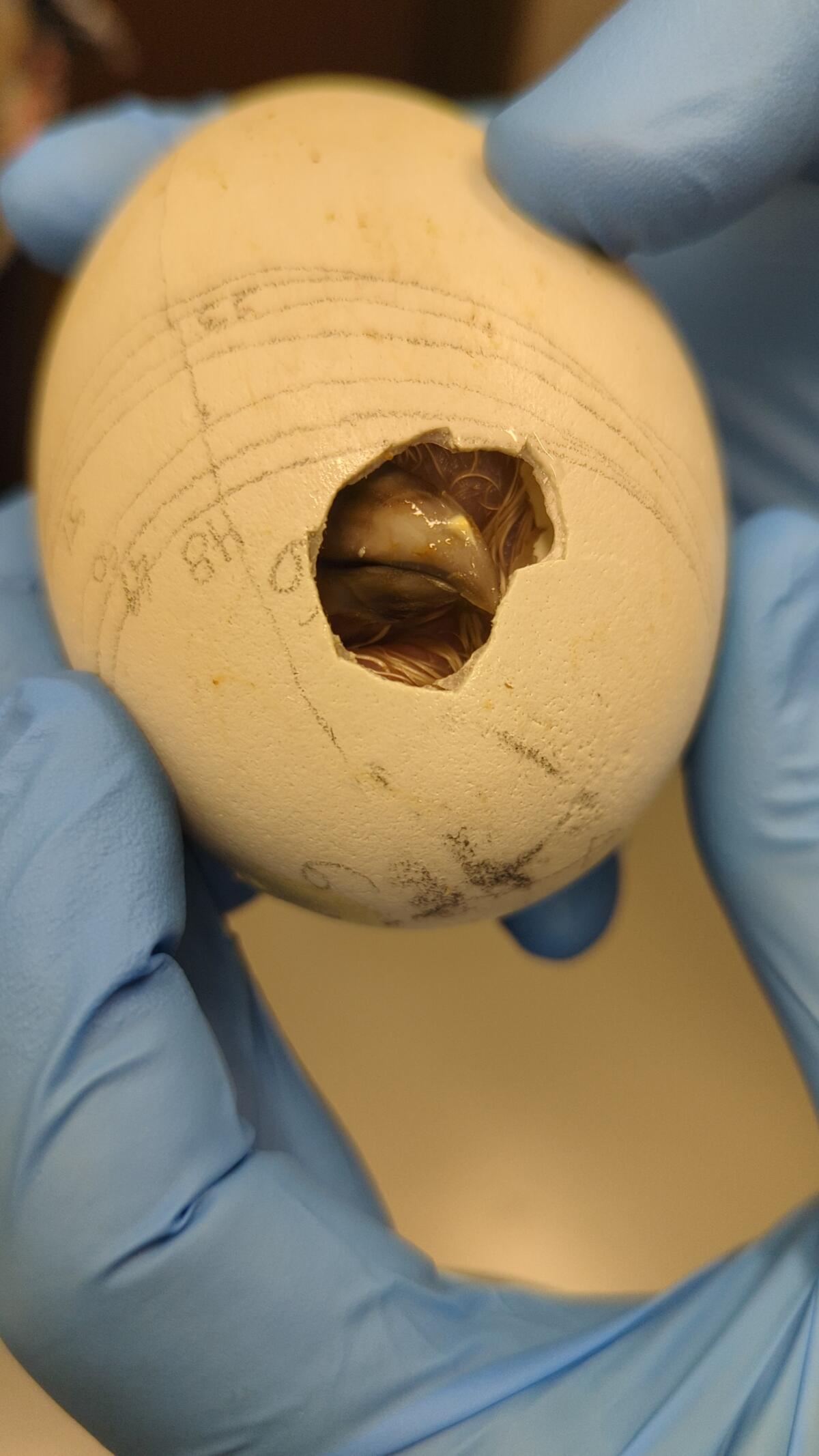

California condor eggs are cared for at L.A. Zoo. The animal is critically endangered.

(Jamie Pham / L.A. Zoo)

This bumper year of condor babies is the result of a modification to a rearing technique pioneered at the L.A. Zoo.

Previously, when the zoo found itself with more fertilized eggs than surrogate adults available, staff raised the young birds by hand. But condors raised by human caretakers have a lower chance of survival in the wild (hence the condor puppets that zookeepers used in the 1980s to prevent young birds from imprinting on human caregivers).

In 2017, the L.A. Zoo experimented with giving an adult bird named Anyapa two eggs instead of one. The gamble was a success. Both birds were successfully released into the wild.

Faced with a large number of eggs this year, “the keepers thought, ‘Let’s try three,’” Myers said. “And it worked.”

The zoo’s condor mentors this season ultimately were able to rear three single chicks, eight chicks in double broods and six chicks in triple broods. The previous record number of 15 chicks was set in 1997.

Condor experts applauded the new strategy.

“Condors are social animals and we are learning more every year about their social dynamics. So I’m not surprised that these chick-rearing techniques are paying off,” said Jonathan C. Hall, a wildlife ecologist at Eastern Michigan University. “I would expect chicks raised this way to do well in the wild.”

The largest land bird in North America with an impressive wingspan up to 9½ feet, the California condor could once be found across the continent. Its numbers began to decline in the 19th century as human settlers with modern weapons moved into the birds’ territory. The scavenger species was both hunted by humans and inadvertently poisoned by lead bullet fragments embedded in carcasses it ate. The federal government listed the birds as an endangered species in 1967.

A condor, one of a record-breaking 17 at the zoo, makes its way out of its shell.

(Jamie Pham / L.A. Zoo)

When the California Condor Recovery Program began four decades ago, there were only 22 California condors left on Earth. As of December, there were 561 living individuals, with 344 of those in the wild. Despite the program’s success in raising the population’s numbers, the species remains critically endangered.

In addition to the ongoing threat of lead poisoning, the large birds are also at risk from other toxins. One 2022 study found more than 40 DDT-related compounds in the blood of wild California condors — chemicals that had made their way from contaminated marine life to the top of the food chain.

“Despite our success in returning condors to the wild, free-flying condors continue to face many obstacles with lead poisoning being the No. 1 cause of mortality,” said Joanna Gilkeson, spokesperson for Fish and Wildlife’s Pacific Southwest Region. “Innovative strategies, like those the L.A. Zoo is implementing, help us to produce more healthy chicks and continue releasing condors into the wild.”

The chicks will remain in the zoo’s care for the next year and a half before they are evaluated for potential release to the wild. Thus far, the zoo has contributed 250 condor chicks to Fish and Wildlife’s program, some of which the agency has redeployed to other zoos as part of its conservation efforts.

In a paper published earlier this year, a team of researchers found that birds born in captivity have slightly lower survival rates for their first year or two but then have equally successful outcomes to wild-hatched birds.

“Because condors reproduce slowly, releases of captive-bred birds are essential to the recovery of the species, especially in light of ongoing losses due to lead-related mortality,” said Victoria Bakker, a quantitative ecologist at Montana State University and lead author of the paper. “The team at the L.A. Zoo should be recognized for their innovative and important contributions to condor recovery.”

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoOne dead after car crashes into restaurant in Paris

-

Midwest1 week ago

Midwest1 week agoMichigan rep posts video response to Stephen Colbert's joke about his RNC speech: 'Touché'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Young Republicans on Why Their Party Isn’t Reaching Gen Z (And What They Can Do About It)

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: A new generation drives into the storm in rousing ‘Twisters’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIn Milwaukee, Black Voters Struggle to Find a Home With Either Party

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics: The Call is Coming from Inside the House

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: J.D. Vance Accepts Vice-Presidential Nomination

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrump to take RNC stage for first speech since assassination attempt