Science

An essential medical device fails people of color. A clinic is suing to fix that

Roots Community Health Center was slammed in 2020, with lines for its COVID-19 testing stations stretching around the block and exam rooms full of people struggling to breathe.

Patient after patient at the East Oakland clinic extended their fingers so that healthcare workers could clip on a pulse oximeter, a device that measures the degree to which red blood cells are saturated with oxygen. For healthy people, a normal “pulse ox” reading is typically between 95% and 100%.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had instructed providers to give oxygen therapy to any COVID patient with a pulse oximeter reading below 90%. Like their counterparts around the country, Roots doctors advised concerned patients to buy inexpensive pulse oximeters so they could monitor their levels at home.

As the pandemic ground on, it became clear that Black and brown patients were dying of COVID at disproportionately high rates, both across the U.S. and in Roots’ own Alameda County.

In the rare hour when she wasn’t in the clinic, Roots founder and Chief Executive Dr. Noha Aboelata paged through medical research in search of answers that might help her patients, the vast majority of whom were Black or brown.

One paper in the New England Journal of Medicine stopped her cold. University of Michigan researchers examined records of thousands of hospitalized COVID patients and looked for instances of “occult hypoxia” — a situation when a patient’s pulse oximeter reads in the healthy range, but their actual blood oxygen levels are dangerously low. The researchers found that this happened to Black patients nearly three times as often as it did to white patients.

Dr. Noha Aboelata said it was “devastating” to realize that researchers had known for years that patients with dark skin were more likely to get false readings from pulse oximeters.

(Carolyn Fong)

Aboelata recalled the “devastating feeling” of diving further into the literature and realizing that this disparity was not a new discovery.

Research dating back to 1990 found that inaccurate pulse oximeter readings were more common in Black patients than non-Black ones. In 2005, detailed lab experiments showed that pulse oximeters frequently overestimated blood oxygen levels in patients with more skin pigmentation.

“This device is really used almost like a vital sign, like you would use a blood pressure cuff,” Aboelata recalled. “How horrified you would feel if you suddenly found out that your blood pressure cuff didn’t work on a certain demographic of your patients?”

She alerted colleagues to the findings and investigated the effect the devices had on the fates of COVID patients of color. She asked the Food and Drug Administration to require pulse oximeter makers to test their devices on people of color and to warn consumers about the heightened risk of false readings. Attorneys for Roots sent letters to companies that made or sold pulse oximeters in California asking them to improve their products and disclose their limitations.

When little changed, Roots filed a lawsuit in November against CVS, Walgreens, GE Healthcare and nine other companies that make, sell or distribute pulse oximeters in California.

“The pigmentation-derived inaccuracies of pulse oximeter readings in people with darker skin consistently skew — or are biased — in one dangerous direction: showing that their blood is more oxygenated than it is in reality,” the lawsuit states. “Individuals with darker skin who use the devices are no less entitled to accurate readings than individuals with lighter skin.”

The suit asks that the companies either find a fix or place warning labels on the products to alert users that skin pigment may affect results.

Before pulse oximeters were widely adopted in the 1980s, the only way to gauge a patient’s blood oxygen saturation was to draw a sample of blood from their arterial vein, a painful procedure that had to be followed by immediate laboratory analysis. The portable, noninvasive oximeters were “a true innovation,” said Dr. Phil Bickler, a neuroanesthesiologist who directs the Hypoxia Research Laboratory at UC San Francisco.

“It’s arguably one of the most important clinical monitors ever devised,” Bickler said, second only to the thermometer.

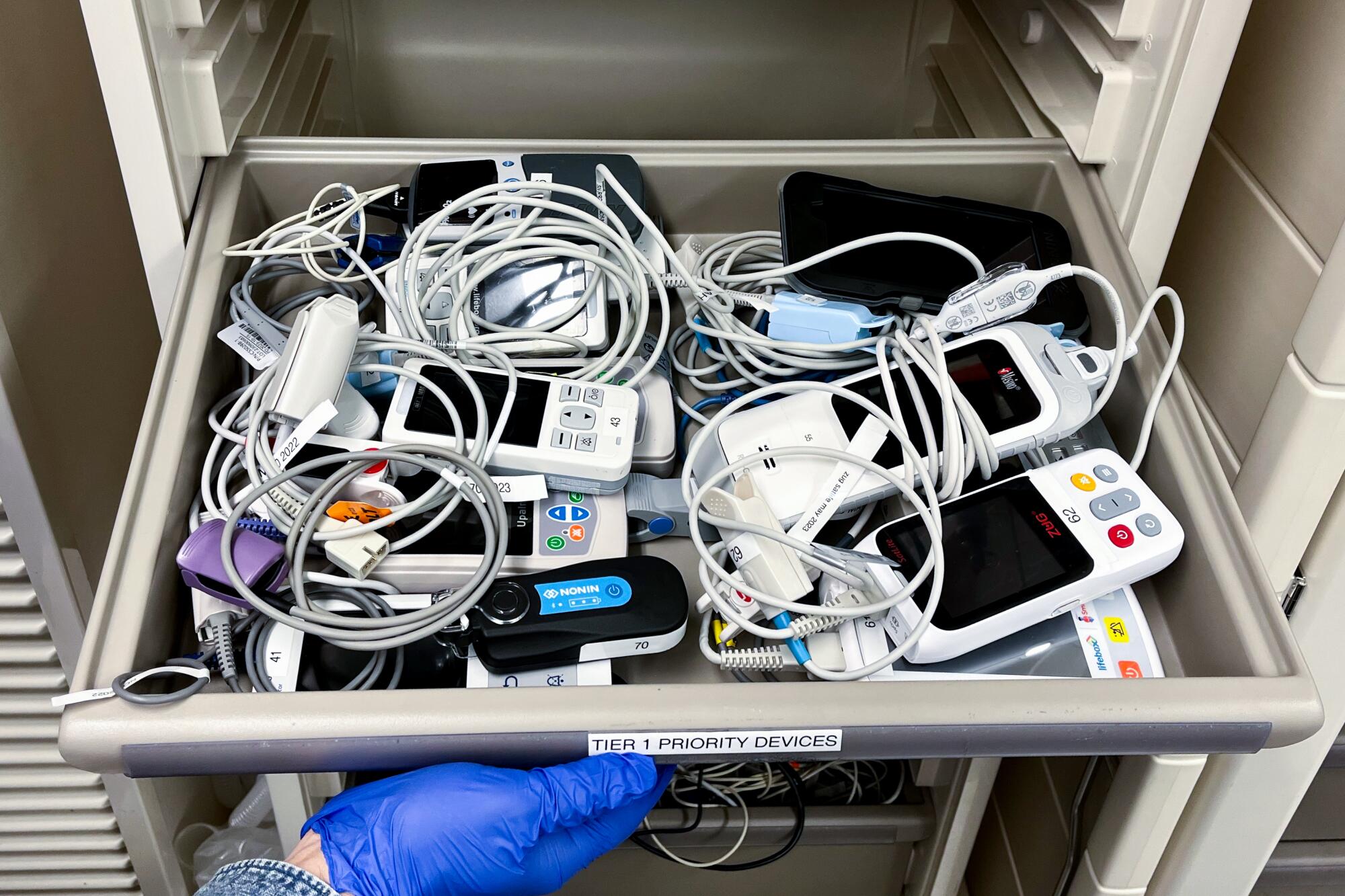

Clinical research coordinator René Vargas Zamora opens a drawer of pulse oximeters at UC San Francisco’s Hypoxia Lab.

(Corinne Purtill/Los Angeles Times)

A pulse oximeter works by shining a light that passes through skin, blood and tissues in the finger and then measuring how much light comes out the other side.

Oxygen-rich blood absorbs more infrared light. So does melanin, the pigment that helps determine skin, hair and eye color. As a result, patients with darker skin tones are more likely to get pulse oximeter readings that show their blood oxygen saturation to be higher than it actually is.

Skin pigment isn’t the only variable that can skew those results. Cold hands, trembling fingers, incorrect probe placement, even nail polish can throw a reading off by a few percentage points too. Knowing this, doctors traditionally used the pulse ox as one data point among many when determining a patient’s course of treatment.

Then COVID-19 hit. As emergency rooms filled and oxygen tanks grew scarce, the CDC anointed pulse oximeter readings as the official standard in its guidelines for COVID care: Below 90%, the patient should be started on oxygen therapy. Above that, it was the doctor’s call.

As the sheer volume of patients grew, so did the number of people with occult hypoxia. Their pulse ox readings were 92% or higher, yet they often had shortness of breath, erratic heartbeats, headaches, confusion and other symptoms of low oxygen saturation.

Many providers around the country also noted that patients with occult hypoxia were more likely to have darker-toned skin.

“Honestly, we had no idea what to make of it,” said Dr. Michael Sjoding, a pulmonologist at the University of Michigan.

He and his colleagues initially wondered whether something about the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself made it harder to detect hypoxia.

Then Sjoding came across an article by Amy Moran-Thomas, a medical anthropologist at MIT. After spending sleepless nights monitoring her husband’s pulse oximeter readings as he suffered through COVID, Moran-Thomas began digging into the history of the device.

She found the 1990 paper that noted hypoxic Black patients were more likely to get deceptively high readings. She found the 2005 study from Bickler’s lab noting the devices were more likely to overestimate oxygen saturation in patients with dark skin than in those with light skin, results the lab confirmed in a follow-up study two years later.

“I was shocked, because I’m a pulmonary critical care physician, I’m a lung doctor, and I didn’t know this whole literature,” Sjoding said.

He and his colleagues pulled data from their own hospital and found Black patients had nearly three times the rate of occult hypoxia as white patients. They published their results in December 2020.

After Aboelata read their paper, she scoured her memory for patients the devices might have betrayed.

She recalled a Black man she had tried to get approved for home oxygen therapy prior to the pandemic. Medicare only paid for the treatment if a patient’s oxygen saturation was below 90%, and “his pulse ox reading just looked too good compared to what I was seeing,” Aboelata said. She sent him to the hospital for an arterial blood gas draw. Sure enough, his oxygen was low enough to qualify.

Patients shared similar stories, “things like, ‘The ambulance didn’t take them to the hospital because they said that their reading was fine,’ or, ‘We were sent home from the emergency department because they said our reading was fine,’” Aboelata said.

In normal times, she said, providers are much more likely to err on the side of caution for a potentially hypoxic patient. But in the worst days of COVID, every bed, oxygen tank and minute was precious. Providers relied on what they believed was the pulse oximeter’s impartial measure to make extremely difficult decisions, unaware that the device did not evaluate all patients equally well.

Aboelata and colleagues from UCSF and Sutter Health’s Institute for Advancing Health Equity published their own study in the American Journal of Epidemiology showing that Black patients whose pulse oximeters overestimated blood oxygen levels waited an extra 4½ hours, on average, to start supplemental oxygen. They were also slightly less likely to be admitted to the hospital or receive oxygen therapy at all.

“There’s just no way to really know how far-reaching this impact is,” Aboelata said. “The likelihood [is] that people were left home to die, or sent home to die.”

In February 2021, the FDA issued a safety notice cautioning users that pulse oximeters can be thrown off by a number of variables, including skin pigment.

The following year, the FDA convened an advisory committee on the topic. The panel recommended the agency demand better consumer labels and more stringent testing from companies seeking approval for their devices.

Currently, the FDA recommends — but doesn’t require — that pulse oximeter makers ensure that in their clinical trials, either two participants or 15% of total participants are “darkly pigmented” people, a definition open to interpretation.

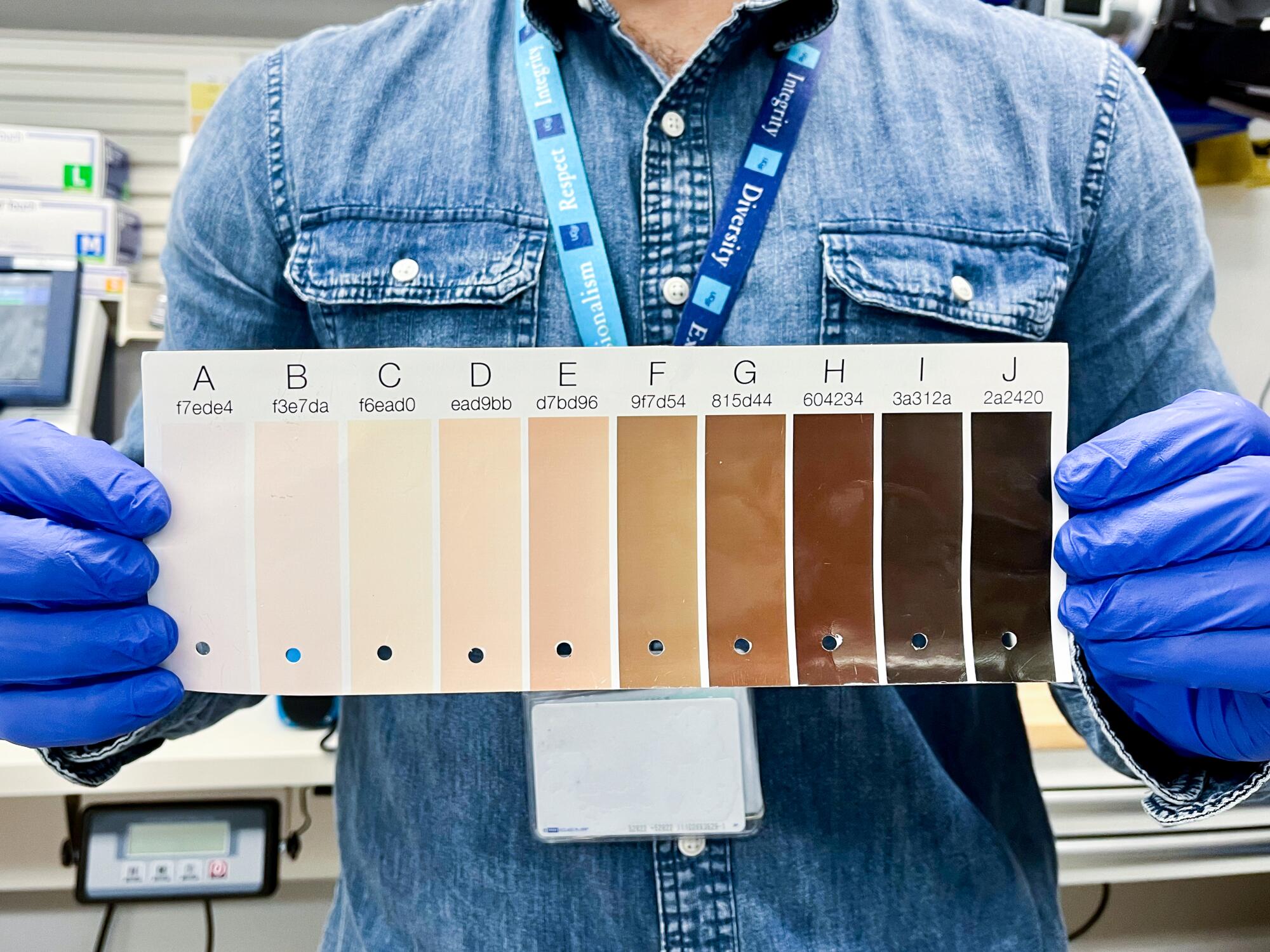

Clinical research coordinator René Vargas Zamora holds up an example of the Monk Skin Tone Scale at UC San Francisco’s Hypoxia Lab.

(Corinne Purtill/Los Angeles Times)

This month, the panel advised the FDA to require that new devices be tested on at least 24 people whose skin tones collectively span the Monk Skin Tone scale, a 10-color palette often used to train artificial intelligences to recognize people of different colors. The proposal would divide the scale into three parts, with each part represented by at least 25% of study participants.

To better understand the relationship between skin pigment and pulse ox accuracy, the FDA funded a study at Bickler’s UCSF lab. Results are expected this summer.

“Some companies have posted data showing good performance with darkly pigmented skin for their devices. But I know that those have been tested under ideal conditions,” said Bickler, whose lab investigates the effects of low oxygen on the human body and the devices that measure it. “When pulse oximeters are used in the real world, conditions are not ideal. People are dehydrated, they’re in shock, they’re moving. There’s all kinds of interference that can happen and that get in the way of good performance.”

For Bickler, it’s gratifying to see the government finally address a problem that has been known for decades but that device manufacturers seemed reluctant to address.

“There’s a lot of inertia and denial in the industry,” he said. “It was an inconvenient problem that could be ignored, up until COVID.”

Dr. Phil Bickler is a neuroanesthesiologist who directs the Hypoxia Research Laboratory at UC San Francisco.

(Corinne Purtill/Los Angeles Times)

The Times reached out to all the defendants being sued by Roots. Those that responded declined to comment on pending litigation.

Only one company has taken actions to address Roots’ concerns. Illinois-based NuvoMed pulled its pulse oximeters from the market in California and agreed to place warning labels on their remaining inventory after receiving Roots’ October letter, said Jonathan Weissglass, the clinic’s attorney.

“Ideally, we’d like the pulse oximeters to be fixed so that the problem doesn’t occur,” Weissglass said. “In the meantime, we feel there needs to be an adequate warning about the inaccuracies for people with darker skin. … We’ve all seen warning labels that say, ‘Pregnant women should consult with a doctor before using’ or something like that. It’s the same basic idea.”

On a recent afternoon at the clinic, medical assistant Evelyn Rivas clipped a pulse oximeter onto Ja-May Scott’s index finger as she checked his vital signs.

The devices are still an important part of Roots’ toolkit. But “we just view it with more suspicion, frankly, in a lot of our patients,” Aboelata said. “We would really like to be equipped with devices that we know can be accurate for all skin tones. And we feel like in 2024, this shouldn’t be too much to ask.”

Science

Q&A: Learn how Olympians keep their cool from Team USA's chief sports psychologist

Your morning jog or weekly basketball game may not take place on an Olympic stage, but you can use Team USA’s techniques to get the most out of your exercise routine.

It’s not all about strength and speed. Mental fitness can be just as important as physical fitness.

That’s why the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee created a psychological services squad to support the mental health and mental performance of athletes representing the Stars and Stripes.

“I think happy, healthy athletes are going to perform at their best, so that’s what we’re striving for,” said Jessica Bartley, senior director of the 15-member unit.

Bartley studied sports psychology and mental health after an injury ended her soccer career. She joined the USOPC in 2020 and is now in Paris with Team USA’s 592 competitors, who range in age from 16 to 59.

Bartley spoke with The Times about how her crew keeps Olympic athletes in top psychological shape, and what the rest of us can learn from them. Her comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Why is exercise good for mental health?

It gets you moving. It gets the endorphins going. And there’s often a lot of social aspects that are really helpful.

There are a number of sports that stretch your brain in ways that can be really, really valuable. You’re thinking about hand-eye coordination, or you’re thinking about strategy. It can improve memory, concentration, even critical thinking.

What’s the best way to get in the zone when it’s time to compete?

When I work with athletes, I like to understand what their zone is. If a 0 or a 1 is you’re totally chilled out and a 10 is you’re jumping around, where do you need to be? What’s your number?

People will say, “I’m at a 10 and I need to be at an 8 or a 7.” So we’ll talk about ways of bringing it down, whether it’s taking a deep breath, listening to relaxing music, or talking to your coach. Or there’s times when people say they need to be more amped up. That’s when you see somebody hitting their chest, or jumping up and down.

If you make a mistake in the middle of a competition, how do you move on instead of dwelling on it?

I often teach athletes a reset routine. I played goalie, so I had a lot of time to think after getting scored on. I would undo my goalie gloves and put them back on, which to me was a reset. I would also wear an extra hairband on my wrist, and when I would snap it, that meant I needed to get out of my head.

It’s not just a physical reset — it helps with a mental reset. If you do the same thing every single time, it goes through the same neural pathway to where it’s going to reset the brain. That can be really impactful.

Do Olympic athletes have to deal with burnout?

Oh, yeah. Everybody has a day where they don’t want to do whatever it is. That’s when you have to ask, “What’s in my best interests? Do I need a recovery day, or do I really need to get in the pool, or get in the gym?”

Sometimes you really do need what we like to refer to as a mental health day.

How can you psych yourself up for a workout when you just aren’t feeling it?

It’s really helpful to think about why you’re doing this and why you’re pushing yourself. Do you have goals related to an activity or sport? Is there something tied to values around hard work or discipline, loyalty or dependability?

When you don’t want to get in the gym, when you don’t want to go for a run, think about something bigger. Tie it back to values.

Is sleep important for maintaining mental health?

Yes! We started doing mental health screens with athletes before the Tokyo Games. We asked about depression, anxiety, disordered eating and body image, drugs and alcohol, and sleep. Sleep was actually our No. 1 issue. It’s been a huge initiative for us.

How much sleep should we be getting?

It’s different for everyone, but generally we know seven to nine hours of sleep is good. Sometimes some of these athletes need 10 hours.

I highly recommend as much sleep as you need. If you didn’t get enough sleep, napping can be really valuable.

Is napping just for Olympic athletes or is it good for everybody?

Everybody! Naps are amazing.

What if there’s no time for a nap?

There are different ways of recharging. Naps could be one of them, but maybe you just need to get off your feet for 20 minutes. Maybe you need to do a meditation or mindfulness exercise and just close your eyes for five minutes.

How do you minimize the effects of jet lag?

We try to shift one hour per day. That’s the standard way of doing it. If you can, it’s super helpful. But it’s not always possible.

The thing we tell athletes is that our bodies are incredible, and you will even things out if you can get back on schedule. One or two nights of crummy sleep is not going to impact your overall performance.

What advice do you give athletes who have trouble falling asleep the night before a competition?

You don’t want to change much right before a competition, so I usually direct athletes to do what they would normally do.

Do you need to unwind by reading a book? Do you need to talk on the phone with somebody and get your mind off things? Can you put your mind in a really restful place and think about things that are really relaxing?

Are there any mindfulness or meditation exercises that you find helpful?

There are some athletes who benefit greatly from an hourlong meditation. I love something quick, something to reset my brain, maybe close my eyes for a minute.

If I’m feeling like I need to take a moment, I love mindful eating. You savor a bite and go, “Oh, my gosh, I have not been fully engaged with my senses today.” Or you could take a mindful walk and take in the sights, the smells, all of the things that are around you.

What do you eat when you need a quick nutrition boost?

Cashews. I tend to carry those with me. They’ve got enough energy to make sure I keep going, physically.

I’ve always got gummy bears on me too. There’s no nutritional value but they keep me going mentally. I’m a big proponent of both.

Is it OK to be superstitious in sports?

It depends how flexible you are. Maybe you put on your socks or shoes a certain way, or listen to certain music. Routines are really soothing. They set your brain up for success in a particular performance. It can be really, really helpful.

But I’ve also seen an athlete forget their lucky underwear or their lucky socks, and they’re all out of sorts. So your routine has to be flexible enough that you’re not going to completely fall apart if you don’t do it exactly.

Are Olympians made of stronger psychological stuff than the rest of us?

Not necessarily. There are some who don’t get feathers ruffled and have a high tolerance for the fanfare. There’s also a lot of regular human beings who just happen to be fantastic at a particular activity.

Science

‘Ready, Steady, Slow’: Championship Snail Racing at 0.006 M.P.H.

Earlier this month, the rural village of Congham, England, played host to a less likely group of athletes: dozens of garden snails. They had gathered to compete in the World Snail Racing Championships, where the world record time for completing the 13.5 inch course stands at 2 minutes flat. At that speed — roughly 0.006 miles per hour — it would take the snails more than six days to travel a mile.

Science

Caring for condor triplets! Record 17 chicks thrive at L.A. Zoo under surrogacy method

A new method of rearing California condors at the Los Angeles Zoo has resulted in a record-breaking 17 chicks hatched this year, the zoo announced Wednesday.

All of the newborn birds will eventually be considered for release into the wild under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s California Condor Recovery Program, a zoo spokesperson said.

“What we are seeing now are the benefits of new breeding and rearing techniques developed and implemented by our team,” zoo bird curator Rose Legato said in a statement. “The result is more condor chicks in the program and ultimately more condors in the wild.”

Breeding pairs of California condors live at the zoo in structures the staff “affectionately calls condor-miniums,” spokesperson Carl Myers said. When a female produces a fertilized egg, the egg is moved to an incubator. As its hatching approaches, the egg is placed with a surrogate parent capable of rearing the chick.

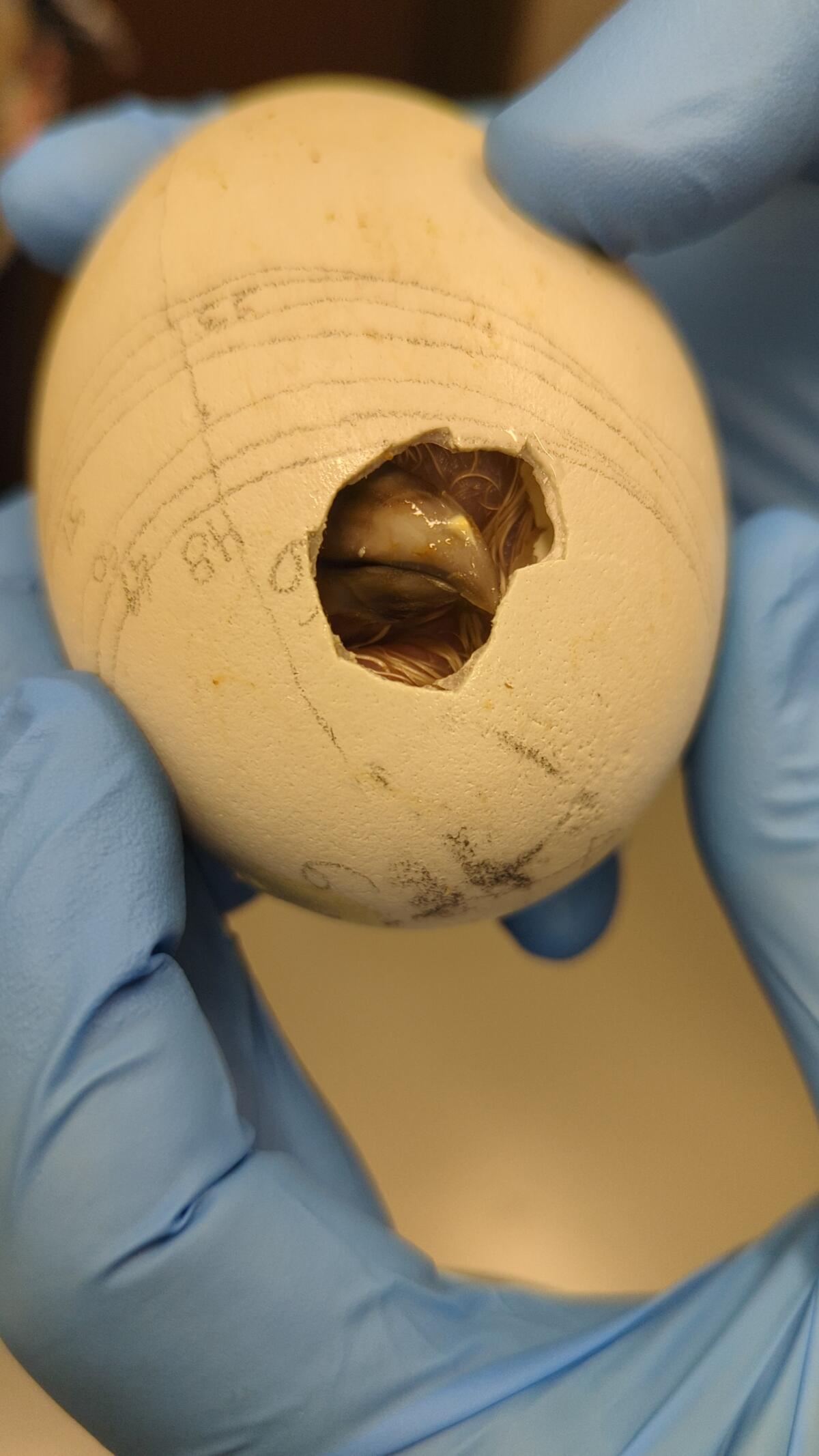

California condor eggs are cared for at L.A. Zoo. The animal is critically endangered.

(Jamie Pham / L.A. Zoo)

This bumper year of condor babies is the result of a modification to a rearing technique pioneered at the L.A. Zoo.

Previously, when the zoo found itself with more fertilized eggs than surrogate adults available, staff raised the young birds by hand. But condors raised by human caretakers have a lower chance of survival in the wild (hence the condor puppets that zookeepers used in the 1980s to prevent young birds from imprinting on human caregivers).

In 2017, the L.A. Zoo experimented with giving an adult bird named Anyapa two eggs instead of one. The gamble was a success. Both birds were successfully released into the wild.

Faced with a large number of eggs this year, “the keepers thought, ‘Let’s try three,’” Myers said. “And it worked.”

The zoo’s condor mentors this season ultimately were able to rear three single chicks, eight chicks in double broods and six chicks in triple broods. The previous record number of 15 chicks was set in 1997.

Condor experts applauded the new strategy.

“Condors are social animals and we are learning more every year about their social dynamics. So I’m not surprised that these chick-rearing techniques are paying off,” said Jonathan C. Hall, a wildlife ecologist at Eastern Michigan University. “I would expect chicks raised this way to do well in the wild.”

The largest land bird in North America with an impressive wingspan up to 9½ feet, the California condor could once be found across the continent. Its numbers began to decline in the 19th century as human settlers with modern weapons moved into the birds’ territory. The scavenger species was both hunted by humans and inadvertently poisoned by lead bullet fragments embedded in carcasses it ate. The federal government listed the birds as an endangered species in 1967.

A condor, one of a record-breaking 17 at the zoo, makes its way out of its shell.

(Jamie Pham / L.A. Zoo)

When the California Condor Recovery Program began four decades ago, there were only 22 California condors left on Earth. As of December, there were 561 living individuals, with 344 of those in the wild. Despite the program’s success in raising the population’s numbers, the species remains critically endangered.

In addition to the ongoing threat of lead poisoning, the large birds are also at risk from other toxins. One 2022 study found more than 40 DDT-related compounds in the blood of wild California condors — chemicals that had made their way from contaminated marine life to the top of the food chain.

“Despite our success in returning condors to the wild, free-flying condors continue to face many obstacles with lead poisoning being the No. 1 cause of mortality,” said Joanna Gilkeson, spokesperson for Fish and Wildlife’s Pacific Southwest Region. “Innovative strategies, like those the L.A. Zoo is implementing, help us to produce more healthy chicks and continue releasing condors into the wild.”

The chicks will remain in the zoo’s care for the next year and a half before they are evaluated for potential release to the wild. Thus far, the zoo has contributed 250 condor chicks to Fish and Wildlife’s program, some of which the agency has redeployed to other zoos as part of its conservation efforts.

In a paper published earlier this year, a team of researchers found that birds born in captivity have slightly lower survival rates for their first year or two but then have equally successful outcomes to wild-hatched birds.

“Because condors reproduce slowly, releases of captive-bred birds are essential to the recovery of the species, especially in light of ongoing losses due to lead-related mortality,” said Victoria Bakker, a quantitative ecologist at Montana State University and lead author of the paper. “The team at the L.A. Zoo should be recognized for their innovative and important contributions to condor recovery.”

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoOne dead after car crashes into restaurant in Paris

-

Midwest1 week ago

Midwest1 week agoMichigan rep posts video response to Stephen Colbert's joke about his RNC speech: 'Touché'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Young Republicans on Why Their Party Isn’t Reaching Gen Z (And What They Can Do About It)

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: A new generation drives into the storm in rousing ‘Twisters’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIn Milwaukee, Black Voters Struggle to Find a Home With Either Party

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics: The Call is Coming from Inside the House

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: J.D. Vance Accepts Vice-Presidential Nomination

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrump to take RNC stage for first speech since assassination attempt