Science

A UCLA doctor is on a quest to free modern medicine from a Nazi-tainted anatomy book

As Dr. Kalyanam Shivkumar pondered how to fix the human heart, he was given a gift laced with horror.

Shivkumar, a cardiac electrophysiologist known as “Shiv” to friends and co-workers at UCLA, was trying to better understand the intricate details of nerves in the chest. He hoped doing so might help him improve treatments for cardiac arrhythmias — aberrant rhythms of the heart — that can prove dangerous and even deadly.

A Canadian colleague sent him a set of anatomy books renowned for the beauty and detail of their drawings, but tipped him off that the “atlas” had an appalling history.

Shivkumar was aghast to learn it was the work of an ardent Nazi whose Vienna institute had dissected the bodies of prisoners, many executed for political reasons after Austria was annexed to Nazi Germany in 1938.

“Every time I open up that book,” he said, “my sense is revulsion.”

Shivkumar is a big thinker, an erudite physician quick with an apt quotation, whose Westwood office is stacked with Sanskrit volumes of the Mahabharata alongside books about late Bruins basketball coach John Wooden.

Dr. Shumpei Mori sets up a donated heart to be photographed at UCLA as part of the Amara Yad project to create new, ethically made anatomical images.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

As he waded into the scholarly debate over using the tainted atlas, the doctor bristled at hearing others praise its illustrations as “unsurpassable.” Much of the soul searching among physicians had revolved around when and how to use it. Shivkumar wanted to put those questions to bed.

“Could we be better?” he asked. “Could we not be making something that’s completely untainted?”

That question would launch Shivkumar on a quest that has lasted more than a decade and is expected to endure for years. He wants to surpass the anatomical atlas created by Dr. Eduard Pernkopf, a fervent supporter of the Nazi regime whose work was fueled by the dead bodies of its victims.

His passion project at the UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center is called Amara Yad, a mashup of Sanskrit and Hebrew meaning “immortal hand.” The work has relied on the generosity of people who have willed their bodies for use at UCLA, as well as hearts that were donated but could not be used for transplant.

So far, Amara Yad has completed two volumes focused on the anatomy of the heart and is enlisting teams at other universities for more. The plan is to draft a freely available, ethically sourced road map to the entire body that eclipses the weathered volumes of watercolors from Pernkopf and honors the Nazis’ victims.

Anatomists have told him, “‘You’re crazy. It’s impossible. How could you ever surpass it?’” Shivkumar said of the Pernkopf atlas in a speech last year before members of the Heart Rhythm Society.

But “can it be beaten? The answer is yes.”

For decades, the origins of the Pernkopf Atlas were unknown to many who turned to its pages for guidance. Swastikas tucked into signatures of an illustrator were airbrushed out in later editions. Its history began to trickle out in journals in the 1980s.

When Dr. Howard Israel finally learned of its roots, he was horrified. Israel, an oral surgeon at Columbia University and self-described “very ordinary American Jew,” told the New York Times he had been relying on the book since he was a medical student.

‘’I felt stupid at using the book,” he told the newspaper, “that I could possibly have benefited from something that sounded so evil.” He and another physician enlisted the Holocaust remembrance group Yad Vashem and publicly pushed for the University of Vienna to investigate whose bodies were depicted in its pages.

The resulting probe found no evidence that the anatomy department under Pernkopf — who had ascended to become dean of the medical faculty at the University of Vienna in 1938 — had received bodies from the Mauthausen concentration camp, as some had wondered.

But the institute had been given at least 1,377 bodies of executed people, most of them sentenced to death for political reasons. Among the charges that led to their executions: “crimes of resistance” and “high treason.”

Using the bodies of executed people was “a centuries-old practice in anatomy,” preferred because anatomists could time their work swiftly after a scheduled death, said Dr. Sabine Hildebrandt, an anatomy educator at Harvard Medical School. What was new under the Nazis, she said, was the sheer number of executions.

The institute “was drowned in bodies,” and “the source for these bodies was mostly connected with the apparatus of repression of the Nazi regime,” said historian Herwig Czech, a member of the Lancet Commission on Medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust, at a recent forum.

By the time those findings emerged, the publisher of the anatomy book had stopped printing it.

1

2

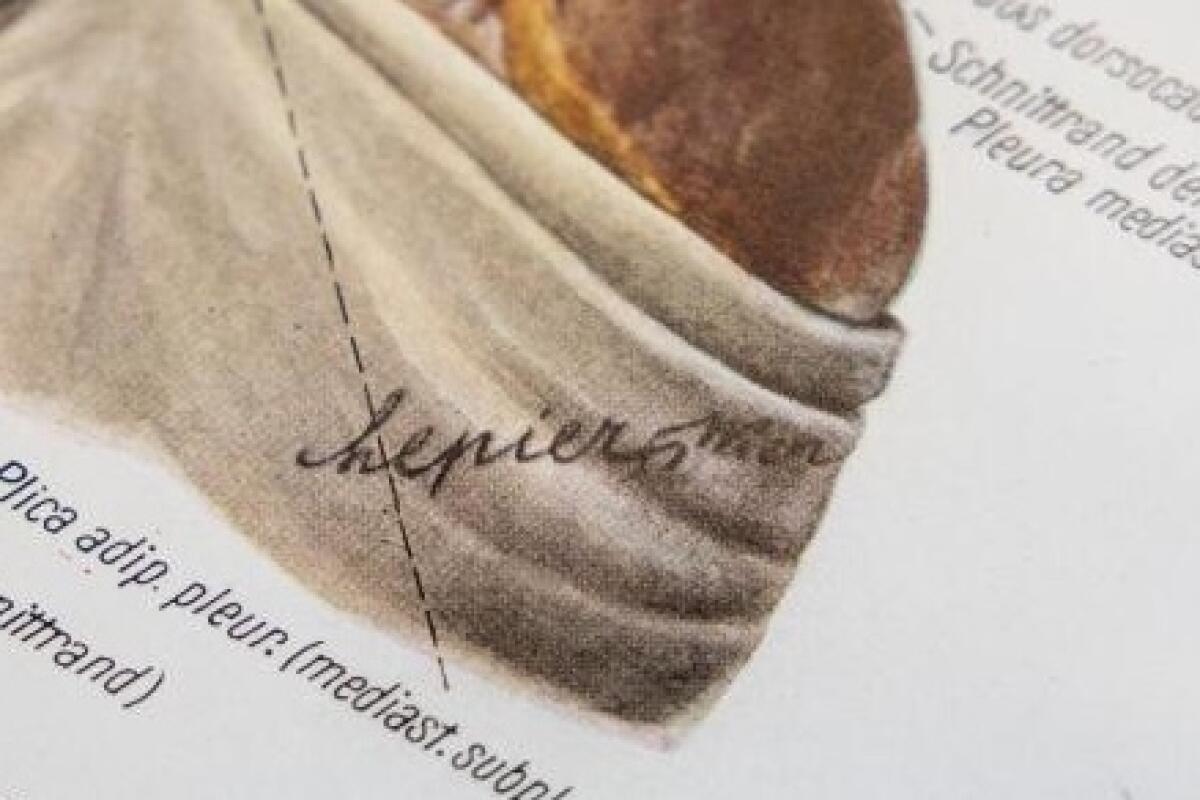

1. A stack of volumes of the Pernkopf atlas on a shelf in Dr. Kalyanam Shivkumar’s UCLA office. 2. Erich Lepier, one of the Pernkopf atlas illustrators, repeatedly included a swastika after the cursive R in his signature. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Yet use of the atlas persisted. Hildebrandt said that a decade ago, dental students in her classes “were basically giving each other thumb drives with bootlegged copies of the head and neck.”

Other anatomical atlases exist, but these illustrations had especially fine details, including of the nerves extending beyond the brain and spiral cord. One survey of nerve surgeons found that 13% of respondents were using the atlas. Among those who have publicly grappled with it is Dr. Susan Mackinnon, a surgery professor at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis known as a pioneer in nerve regeneration.

“I used this textbook for years before I knew the history of it,” she said. “My brain is contaminated with that. I can’t undo that.”

Mackinnon sought ethical guidance. Rabbi Joseph Polak, a Boston University assistant adjunct professor of health law who survived the concentration camps as a child, said one dilemma involved a patient in excruciating pain.

Polak recalled that the patient had told Mackinnon that “if you can’t find the nerve to stop the pain, then I want my leg amputated.” The rabbi walked through Jewish teachings that applied to the ethical quandary and conferred with other experts, penning a set of recommendations called the Vienna Protocol.

Among his urgings to doctors: If you use these drawings, make it clear to patients where they came from.

The Third Reich wanted “to extinguish them and to extinguish eventually all memory of them,” the rabbi said of Holocaust victims, speaking at a recent forum about the atlas. But when a doctor tells patients about what happened to the people depicted in the drawings, he said, “they’re being called out of that darkness.”

Mackinnon now keeps the atlas locked away. In the rare cases she feels she needs to consult it to operate, she tells patients and co-workers about the man behind it. His firings of Jewish doctors. The grim details in its pages — shorn hair, emaciated bodies — that began to raise suspicions about its terrible origins.

The only reason to use it, she said, is to save someone from misery — and only if “nothing else will help you.”

“Could we be better” than Pernkopf? Shivkumar asked. “Could we not be making something that’s completely untainted?”

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Shivkumar said his goal is to eliminate the need to consult those pages at all. Inside UCLA’s Center for the Health Sciences in Westwood, he showed off a donated heart, prepped and ready for its close-up in a corner of the lab outfitted with a black backdrop and brilliant lights.

A spent heart normally wilts like a deflated balloon, but this one had been pumped with chemicals to imitate the fullness of life. The team first puts the organs to use in research, then carefully dissects them for imaging.

Bringing out a bisected piece of a heart, Dr. Shumpei Mori displayed how its inner architecture could be captured on camera, threading a catheter through the organ as a co-worker snaked in an endoscope.

“The internal structure is really fine and delicate,” said Mori, a specialist in cardiac anatomy who had jumped at the chance to do something new in the field.

“Even Pernkopf simplified the anatomy” in its drawings, Mori said. “What we are doing is more complicated.”

Dr. Shumpei Mori holds a detailed model of a heart. “Even Pernkopf simplified the anatomy,” he said. “What we’re doing is more complicated.”

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The camera is far from their only tool: The team has generated 3-D images to illustrate the dimensions of the inner structures of the heart; done CT scans to produce hand-held models; and used sophisticated imaging from a microscope to reveal the lattice of nerves connecting to the organ — part of the signaling system that Shivkumar calls “the internet of the human body.”

In another lab, Mori carefully unzipped a bag on a metal gurney to reveal the stripped-down interior of a cadaver diligently dissected over a year and a half, its rib cage cracked open like a weighty book. Shivkumar pointed out the pale web of nerves stretching up through the neck. Mori had painted them yellow by hand.

The human body might seem like well-traveled territory, but as physicians work to find less invasive ways of healing, such as attacking a cancer with ultrasound, Shivkumar said there is “a volcanic desire for this kind of information.” Snip the right nerve, he said, and you can avert the need for a heart transplant.

“Pernkopf never did nerves like this,” he said with pride.

Amara Yad is also an act of “moral repair” meant to honor the victims, said Dr. Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, a UCLA cardiologist and evolutionary biologist who helped support the project. The Nazi atlases “were like documents of death. The atlases that Shiv is creating are really living, interactive tools to support life.”

When Shivkumar decided to launch the project, he had been inspired by the words of USC emeritus professor of rheumatology Dr. Richard Panush, who had pushed to set the atlas aside in the library of the New Jersey medical center where he had worked, moving it to a display case that explained its history.

Panush said the old atlas should be preserved only as “a symbol of what we should not do, and how we should not behave, and the kind of people that we cannot respect.”

Doctors need to know that history to understand their own moral fallibility, Hildebrandt said. Physicians in Nazi Germany “still thought they were doing the right thing,” she said, even as they failed to see some people as human.

Rabbi Polak stressed that doctors at the time “had the deepest, most profound respect of the masses.”

Yet when the Nazis took power, “it turned out that a vast proportion of them were moral sleazeballs,” Polak said. “They were the first to join when they saw that it could promote their careers.”

Model hearts line a bookshelf at UCLA. The Amara Yad project is working with other universities to tackle other parts of human anatomy.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Shivkumar said that beyond making new tools for physicians, the Amara Yad project is working with Oxford University to develop an accompanying curriculum that will explore ethical failures in medicine. Pernkopf’s anatomy book is only one example.

The history of the atlas “invites the contemplation of how doctors and medical scientists and anatomists are related to a regime,” said Sari J. Siegel, who heads the Center for Medicine, Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Cedars-Sinai. Thinking about it underscores that “medicine is political.”

“It can’t be divorced from the larger contexts in which it exists.”

Shivkumar, born to a Hindu family in the southernmost state of India, is used to people wondering why he became “possessed” with this project. He recalls first learning about the Holocaust from a photographer friend of his grandfather, a former newspaper editor once imprisoned for sedition against the British Empire.

He was 11 when the photographer showed him images dating to World War II, and it chilled him “to see that human beings could be so brutal to other humans.” As a child, his parents had told him they owed the world because their part of India was lucky to be long spared from such conflict.

In Amara Yad, we “get a rare opportunity in history to correct an unbelievably depressing stain that was placed in our field,” he told the Heart Rhythm Society.

It irritates him to think of the abundant resources that a Nazi had at hand to do this sort of work. “Imagine having five Shumpeis!” he exclaimed at one point, gesturing at his colleague who hand painted the nerves. At UCLA, the project has piggybacked on ongoing research and relied on donations. He is hoping to garner $500,000 annually to continue and expand the work.

But Shivkumar likes to quote the Emperor Ashoka on that point: “To do good is difficult. One who does good first does something hard to do. … Truly, it is easy to do evil.”

Science

After rash of overdose deaths, L.A. banned sales of kratom. Some say they lost lifeline for pain and opioid withdrawal

Nearly four months ago, Los Angeles County banned the sale of kratom, as well as 7-OH, the synthetic version of the alkaloid that is its active ingredient. The idea was to put an end to what at the time seemed like a rash of overdose deaths related to the drug.

It’s too soon to tell whether kratom-related deaths have dissipated as a result — or, really, whether there was ever actually an epidemic to begin with. But many L.A. residents had become reliant on kratom as something of a panacea for debilitating pain and opioid withdrawal symptoms, and the new rules have made it harder for them to find what they say has been a lifesaving drug.

Robert Wallace started using kratom a few years ago for his knees. For decades he had been in pain, which he says stems from his days as a physical education teacher for the Glendale Unified School District between 1989 and 1998, when he and his students primarily exercised on asphalt.

In 2004, he had arthroscopic surgery on his right knee, followed by varicose vein surgery on both legs. Over the next couple of decades, he saw pain-management specialists regularly. But the primary outcome was a growing dependence on opioid-based painkillers. “I found myself seeking doctors who would prescribe it,” he said.

He leaned on opioids when he could get them and alcohol when he couldn’t, resulting in a strain on his marriage.

When Wallace was scheduled for his first knee replacement in 2021 (he had his other knee replaced a few years later), his brother recommended he take kratom for the post-surgery pain.

It seemed to work: Wallace said he takes a quarter of a teaspoon of powdered kratom twice a day, and it lets him take charge of managing his pain without prescription painkillers and eases harsh opiate-withdrawal symptoms.

He’s one of many Angelenos frustrated by recent efforts by the county health department to limit access to the drug. “Kratom has impacted my life in only positive ways,” Wallace told The Times.

For now, Wallace is still able to get his kratom powder, called Red Bali, by ordering from a company in Florida.

However, advocates say that the county crackdown on kratom could significantly affect the ability of many Angelenos to access what they say is an affordable, safer alternative to prescription painkillers.

Kratom comes from the leaves of a tree native to Southeast Asia called Mitragyna speciosa. It has been used for hundreds of years to treat chronic pain, coughing and diarrhea as well as to boost energy — in low doses, kratom appears to act as a stimulant, though in higher doses, it can have effects more like opioids.

Though advocates note that kratom has been used in the U.S. for more than 50 years for all sorts of health applications, there is limited research that suggests kratom could have therapeutic value, and there is no scientific consensus.

Then there’s 7-OH, or 7-Hydroxymitragynine, a synthetic alkaloid derived from kratom that has similar effects and has been on the U.S. market for only about three years. However, because of its ability to bind to opioid receptors in the body, it has a higher potential for abuse than kratom.

Public health officials and advocates are divided on kratom. Some say it should be heavily regulated — and 7-OH banned altogether — while others say both should be accessible, as long as there are age limitations and proper labeling, such as with alcohol or cannabis.

In the U.S., kratom and 7-OH can be found in all sorts of forms, including powder, capsules and liquids — though it depends on exactly where you are in the country. Though the Food and Drug Administration has recommended that 7-OH be included as a Schedule 1 controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act, that hasn’t been made official. And the plant itself remains unscheduled on the federal level.

That has left states, counties and cities to decide how to regulate the substances.

California failed to approve an Assembly bill in 2024 that would have required kratom products to be registered with the state, have labeling and warnings, and be prohibited from being sold to anyone younger than 21.

It would also have banned products containing synthetic versions of kratom alkaloids. The state Legislature is now considering another bill that basically does the same without banning 7-OH — while also limiting the amount of synthetic alkaloids in kratom and 7-OH products sold in the state.

“Until kratom and its pharmacologically active key ingredients mitragynine and 7-OH are approved for use, they will remain classified as adulterants in drugs, dietary supplements and foods,” a California Department of Public Health spokesperson previously told The Times.

On Tuesday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state’s efforts to crack down on kratom products has resulted in the removal of more than 3,300 kratom and 7-OH products from retail stores. According to a news release from the governor’s office, there has been a 95% compliance rate from businesses in removing the products.

(Los Angeles Times photo illustration; source photos by Getty Images)

Newsom has equated these actions to the state’s efforts in 2024 to quash the sale of hemp products containing cannabinoids such as THC. Under emergency state regulations two years ago, California banned these specific hemp products and agents with the state Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control seized thousands of products statewide.

Since the beginning of 2026, there have been no reported violations of the ban on sales of such products.

“We’ve shown with illegal hemp products that when the state sets clear expectations and partners with businesses, compliance follows,” Newsom said in a statement. “This effort builds on that model — education first, enforcement where necessary — to protect Californians.”

Despite the state’s actions, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors is still considering whether to regulate kratom, or ban it altogether.

The county Public Health Department’s decision to ban the sale of kratom didn’t come out of nowhere. As Maral Farsi, deputy director of the California Department of Public Health, noted during a Feb. 18 state Senate hearing, the agency “identified 362 kratom-related overdose deaths in California between 2019 and 2023, with a steady increase from 38 in 2019 up to 92 in 2023.”

However, some experts say those numbers aren’t as clear-cut as they seem.

For example, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that in a number of recent L.A. County deaths that were initially thought to be caused by kratom or 7-OH, there wasn’t enough evidence to say those drugs alone caused the deaths; it might be the case that the danger is in mixing them with other substances.

Meanwhile, the actual application of this new policy seems to be piecemeal at best.

The county Public Health Department told The Times it conducted 2,696 kratom-related inspections between Nov. 10 and Jan. 27, and found 352 locations selling kratom products. The health department said the majority stopped selling kratom after those inspections; there were nine locations that ignored the warnings, and in those cases, inspectors impounded their kratom products.

But the reality is that people who need kratom will buy it on the black market, drive far enough so they get to where it’s sold legally or, like Wallace, order it online from a different state.

For now, retailers who sell kratom products are simply carrying on until they’re investigated by county health inspectors.

Ari Agalopol, a decorated pianist and piano teacher, saw her performances and classes abruptly come to a halt in 2012 after a car accident resulted in severe spinal and knee injuries.

“I tried my best to do traditional acupuncture, physical therapy and hydrocortisone shots in my spine and everything,” she said. “Finally, after nothing was working, I relegated myself to being a pain-management patient.”

She was prescribed oxycodone, and while on the medication, battled depression, anhedonia and suicidal ideation. She felt as though she were in a fog when taking oxycodone, and when it ran out, ”the pain would rear its ugly head.” Agalopol struggled to get out of bed daily and could manage teaching only five students a week.

Then, looking for alternatives to opioids, she found a Reddit thread in which people were talking up the benefits of kratom.

“I was kind of hesitant at first because there’re so many horror stories about 7-OH, but then I researched and I realized that the natural plant is not the same as 7-OH,” she said.

She went to a local shop, Authentic Kratom in Woodland Hills, and spoke to a sales associate who helped her decide which of the 47 strains of kratom it sold would best suit her needs.

Agalopol currently takes a 75-milligram dose of mitragynine, the primary alkaloid in kratom, when necessary. It has enabled her to get back to where she was before her injury: teaching 40 students a week and performing every weekend.

Agalopol believes the county hasn’t done its homework on kratom. “They’re just taking these actions because of public pressure, and public pressure is happening because of ignorance,” she said.

During the course of reporting this story, Authentic Kratom has shut down its three locations; it’s unclear if the closures are temporary. The owner of the business declined to comment on the matter.

When she heard the news of the recent closures, Agalopol was seething. She told The Times she has enough capsules of kratom for now, but when she runs out, her option will have to be Tylenol and ibuprofen, “which will slowly kill my liver.”

“Prohibition is not a public health strategy,” said Jackie Subeck, executive director of 7-Hope Alliance, a nonprofit that promotes safe and responsible access to 7-OH for consumers, at the Feb. 18 Senate hearing. “[It’s] only going to make things worse, likely resulting in an entirely new health crisis for Californians.”

Science

There were 13 full-service public health clinics in L.A. County. Now there are 6

Because of budget cuts, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health has ended clinical services at seven of its public health clinic sites.

As of Feb. 27, the county is no longer providing services such as vaccinations, sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment, or tuberculosis diagnosis and specialty TB care at the affected locations, according to county officials and a department fact sheet.

The sites losing clinical services are Antelope Valley in Lancaster; the Center for Community Health (Leavy) in San Pedro, Curtis R. Tucker in Inglewood, Hollywood-Wilshire, Pomona, Dr. Ruth Temple in South Los Angeles, and Torrance. Services will continue to be provided by the six remaining public health clinics, and through nearby community clinics.

The changes are the result of about $50 million in funding losses, according to official county statements.

“That pushed us to make the very difficult decision to end clinical services at seven of our sites,” said Dr. Anish Mahajan, chief deputy director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Mahajan said the department selected clinics with relatively lower patient volumes. Over the last month, he said, the department has sent letters to patients about the changes, and referred them to unaffected county clinics, nearby federally qualified health centers or other community providers. According to Mahajan, for tuberculosis patients, particularly those requiring directly observed therapy, public health nurses will continue visiting patients.

Public health clinics form part of the county’s healthcare safety net, serving low-income residents and those with limited access to care. Officials said that about half of the patients the county currently sees across its clinics are uninsured.

Mahajan noted that the clinics were established decades ago, before the Affordable Care Act expanded Medi-Cal coverage and increased the number of federally qualified health centers. He said that as more residents gained access to primary care, utilization at some county-run clinics declined.

“Now that we have a more sophisticated safety net, people often have another place to go for their full range of care,” he said.

Still, the closures have unsettled providers who work closely with local vulnerable populations.

“I hate to see any services that serve our at-risk and homeless community shut down,” said Mark Hood, chief executive of Union Rescue Mission in downtown Los Angeles. “There’s so much need out there, so it always is going to create hardship for the people that actually need the help the most.”

Union Rescue Mission does not receive government funding for its healthcare services, Hood said. The mission’s clinics are open not only to shelter guests, up to 1,000 people nightly, but also to people living on the streets who walk in seeking care.

Its dental clinic alone sees nearly 9,000 patients a year, Hood said.

“We haven’t seen it yet, but I expect in the coming days and weeks we’ll see more people coming through our doors looking for help,” he said. “They’re going to have to find help somewhere.” Hood said women experiencing homelessness are especially vulnerable when preventive care, including sexual and reproductive health services, becomes harder to access.

County officials said staffing impacts so far have been managed through reassignment rather than layoffs. Roughly 200 to 300 positions across the department have been eliminated amid funding cuts, officials said, though many were vacant. About 120 employees whose positions were affected have been reassigned; according to Mahajan, no one has been laid off.

The clinic closures come amid broader fiscal uncertainty. Mahajan said that due to the Trump administration’s “Big Beautiful Bill,” Los Angeles County could lose $2.4 billion over the next several years. That funding, he said, supports clinics, hospitals and community clinic partners now absorbing patients who previously went to the clinics that closed on Feb. 27.

In response, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors has backed a proposed half-cent sales tax measure that would generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually for healthcare and public health services. Voters are expected to consider the measure in June.

Science

Mobile clinic brings mammograms to women on Skid Row

Sharon Horton stepped through the door of a sky-blue mobile clinic and onto a Skid Row sidewalk. She wore a yellow knit beanie, gold hoop earrings and the relieved grin of a woman who has finally checked a mammogram off her to-do list.

It had been years since her last breast cancer screening procedure. This one, which took place in City of Hope’s Cancer Prevention and Screening mobile clinic, was faster and easier. The staff was kind. The machine that X-rayed her breast was more comfortable than the cold hard contraption she remembered.

Relatively speaking, of course — it was still a mammogram.

“It’s like, OK, let me go already!” Horton, 68, said with a laugh.

The clinic was parked on South San Pedro Street in front of Union Rescue Mission, the nonprofit shelter where Horton resides. Within a week, City of Hope, a cancer research hospital, would share the results with Horton and Dr. Mary Marfisee, the mission’s family medical services director. If the mammogram detected anything of concern, they’d map out a treatment plan from there.

Naureen Sayani, 47, a resident of Union Rescue Mission, left, discusses her medical history with Adriana Galindo, a medical assistant, before getting a mammogram on last week.

(Kayla Bartkowski / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s very important to take care of your health, and you need to get involved in everything that you can to make your life a better life,” said Horton, who is looking forward to a forthcoming move into Section 8 housing.

Horton was one of the first patients of a new women’s health initiative from UCLA’s Homeless Healthcare Collaborative at Union Rescue Mission. Staffed by third-year UCLA Medical School students and led by Marfisee, a UCLA assistant clinical professor of family medicine, the clinic treats mission residents as well as unhoused people living in the surrounding neighborhood.

The new cancer screening project arrives at a time of dire financial pressures on county public health services.

Citing rising costs and a $50-million reduction in federal, state and local grant and contract income, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health on Feb. 27 ended services at seven of 13 public clinics that provide vaccines, tests and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases and other services to housed and unhoused county residents.

Although Union Rescue Mission’s own funding comes mainly from private sources and is less imperiled by public cuts, the 135-year-old shelter expects the need for its services to rise, Chief Executive Mark Hood said.

Even as unsheltered homelessness declined for the last two years across Los Angeles County, the unsheltered population on Skid Row — long seen as the epicenter of the region’s homelessness crisis — grew 9% in 2024, the most recent year for which census data are available.

For many local women navigating daily concerns over housing, food and personal safety, “their own health is not a priority,” Marfisee said.

Those whose problems have become too serious to ignore face daunting obstacles to care. Marfisee recalled one patient who came to her with a lump in her breast and no identification.

In order to get a mammogram, Marfisee explained, the woman first needed to obtain a birth certificate, and then a state-issued identification card. Then she needed to enroll in Medi-Cal. After that, clinic staff helped her find a primary care physician who could order the imaging test.

Given the barriers to preventative care, homeless women die from breast cancer at nearly twice the rate of securely housed women, a 2019 study found. Marfisee’s own survey of the mission’s female residents found that nearly 90% were not up to date on recommended cancer screenings like mammograms and pap smears, which detect early cervical cancer.

To address this gap, Marfisee — a dogged patient advocate — reached out to City of Hope. The Duarte-based research and treatment center unveiled in March 2024 its first mobile cancer screening clinic, a moving van-sized clinic on wheels that it deploys to food banks and health centers, as well as to companies offering free mammograms as an employee benefit.

“In true Dr. Mary fashion, she saw the vision,” said Jessica Thies, the mobile screening program’s regional nursing director. After working through some logistical hurdles, the mission and City of Hope secured a date for the van’s first visit.

The next challenge was getting the word out to patients. Marfisee and her students walked through the surrounding neighborhood, went cot to cot in the women’s dorm and held two informational sessions in December and January to answer patients’ questions.

At the sessions, the team walked through the basics of who should get a mammogram (women age 40 or older, those with a family history of breast cancer) and the procedure itself. (“Like a tortilla maker?” one woman asked skeptically after hearing a description of the mammography unit.)

The medical students were able to dispel rumors some women had heard: The test doesn’t damage breast tissue, nor do the X-rays increase cancer risk. Others questioned a mammogram’s value: What good was it knowing they had cancer if they couldn’t get follow-up care?

On this latter point, Marfisee is determined not to let patients fall through the cracks.

Thirteen patients received mammograms at the van’s first visit on Wednesday. Within a week, City of Hope will contact patients with their results and send them to Marfisee and her team. She is already mentally mapping the next steps should any patient have a situation that requires a biopsy or further imaging: working with their case manager at the mission, calling in favors, wrangling with any insurance the patient might have.

“It’ll be a good fight,” Marfisee said, as residents in the adjacent cafeteria carried trays of sloppy joes and burgers to their lunch tables. “But we’ll just keep asking for help and get it done.”

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling