Science

A Powerful Climate Solution Just Below the Ocean’s Surface

They can bolster the coastlines, break the force of hurtling waves, provide housing for fish, shellfish, and migrating birds, clean the water, store as much as 5 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide, and pump oxygen into the ocean, in part making it possible for life on Earth as we know it.

These miracle machines are not the latest shiny tech invention. Rather, they are one of nature’s earliest floral creations: seagrasses. Anchored on the shorelines of every continent except Antarctica, these plants (and they are plants, not algae, that sprout, flower, fruit and go to seed) are one of the most powerful but unheralded climate solutions that already exist on the planet.

Restoring seagrass is one tool that coastal communities can use to address climate change, both by capturing emissions and mitigating their effects, which is among the topics being discussed as leaders in business, science, culture and policy gather on Thursday and Friday in Busan, South Korea, for a New York Times conference, A New Climate.

Around the world, scientists, nongovernmental organizations and volunteers are working to restore seagrass meadows, if not to their original glory, then to something far more expansive and majestic than the barren, muddy bottoms left behind when they are damaged or destroyed.

In Virginia, parts of Britain and Western Australia, among other places, with the helping hands of committed researchers and citizen scientists alike, seagrass meadows are coming back. They’re bringing with them clearer waters, stabler shores, and animals and other organisms that used to thrive there. And yet, seagrass doesn’t get the attention it deserves, its partisans say.

It’s impossible to know exactly how much seagrass has been lost, because scientists don’t know how much there was to begin with.

Only about 16 percent of global coastal ecosystems are considered intact, and seagrasses are among the hardest hit. It’s estimated that a third of seagrass around the world has disappeared in the last few decades, according to Matthew Long, an associate scientist in marine chemistry and geochemistry at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “Globally, a soccer field of seagrass is lost every 30 minutes,” Dr. Long said, “and we lose about 5 to 10 percent at an accelerated rate every single year.”

“Seagrasses are adversely affected by global stressors: deoxygenation, ocean acidification and warming temperatures,” Dr. Long said. But local stressors also have played a role in their withering, mainly in the form of nutrient pollution, largely from agricultural runoff and wastewater, and subsequent algal blooms and die-offs, which first choke out other plants like seagrass (a process called eutrophication) and then, as they decompose, take up all the oxygen in the water (hypoxia).

While the effects of climate change and growing human impacts have accelerated seagrass loss in the last few decades, it’s not a new story.

On the Eastern Shore of Virginia, a strong storm in August 1933 that followed a wasting disease and overharvesting of bay scallops, wiped out what remained of once vast eelgrass meadows. (Eelgrass is a type of seagrass.) For decades, there was no eelgrass on the shore’s ocean side, said Bo Lusk, a scientist with the Nature Conservancy’s Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve, though some remained on the part of the coast lapped by the Chesapeake Bay.

Dr. Lusk, who grew up in the region, heard stories as a child of lush green carpets of eelgrass from his grandmother, who remembered that the shores teemed with life — until they didn’t. But then, in 1997, someone reported seeing some patches of eelgrass on the shore’s oceanside, likely from seeds that happened to drift south from Maryland and settled in a hospitable neighborhood in Virginia.

After several years of experiments, Robert J. Orth, a scientist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, devised a highly successful method of restoring seagrass, similar to methods used around the world: In the spring, scientists and hundreds of volunteers collect seeds, which they count and process over the summer and plant in the sediment in the fall.

Since 2003, when the restoration effort in the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve began, scientists and others have planted around 600 acres of seeds, and seagrass now covers 10,000 acres, according to Dr. Lusk. Later this year, the Nature Conservancy is hoping to sell the first validated blue carbon credits for seagrass, based on this restoration effort, said Jill Bieri, the director of the reserve.

However, the success of the Virginia project has been somewhat difficult to recreate around the world. “You can’t do this just anywhere,” Dr. Lusk said. “If the Nature Conservancy hadn’t started this land protection work 50 years ago, buying up parts of the coast to preserve it, the odds are we wouldn’t have the water quality we have now, and this wouldn’t have been so successful.”

Seagrass restoration will take decades of commitment, Dr. Lusk said. Richard Unsworth, an associate bioscience professor at Swansea University in Wales and the founder and chief scientific officer of Project Seagrass, a British NGO that works on seagrass restoration, said that an important part of the work was the long-term promise made to the whole ecosystem — the seagrass meadows, but also the people in the community.

“The actions of fishermen, the views of boat owners, the problems of water quality — they can all be part of a complex social-cultural situation, and in the long term it will be an amazing success, but it’s a slow process, not some silver bullet where you plant something and then you’ve saved it,” Dr. Unsworth said.

Community engagement has been a necessary part for seagrass success since it takes a lot of work to collect and plant millions of seeds. For Project Seagrass, that has also meant the development of a website and app, Seagrass Spotter, which allows users to upload photos of seagrass in the wild (which is then verified by scientists), to help researchers fully map the extent and types of seagrasses around the world, since mapping of seagrass globally is rather patchy.

But one place it’s well mapped is Shark Bay, a remote section of the coast in Western Australia, where seagrass from 10 different meadows was discovered to be actually just one plant, possibly the biggest in the world.

There, seagrass has been growing and accumulating carbon in its plant matter, but also in the sediment, for more than 3,000 years, said Elizabeth Sinclair, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Western Australia.

But during an extreme marine heat wave from 2010 to 2011, about a third of the seagrass canopy (what is visible above the sand) died, releasing as much as nine million tons of carbon, according to one estimate.

Over the last decade or so, Dr. Sinclair and her colleagues have been studying the recovery of the seagrass — the places where it’s come back naturally and where it likely never will, without some assistance from scientists as well as the Malgana people, Indigenous Australians who work as rangers.

Despite warming temperatures and changing ocean chemistry, which make complete restoration impossible, it’s still work worth doing, said Dr. Lusk, whether it’s on the crooked waterways of the Virginia coast, the rocky shores of Wales, or the sweeping, endless bays of Western Australia.

“There are so many logical reasons we should do this,” Dr. Lusk said. “The carbon storage is great, shoreline protection, all of this other stuff is great, and you can know that in your head but until you get in the water and spend some time really within this system, you don’t have the emotional connection.

“I would keep doing this if there was no carbon stored. It just feels right to be out there.”

Science

NASA’s JPL cuts 550 jobs in latest round of layoffs at La Cañada Flintridge facility

Layoff notices went out Tuesday to 550 employees at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in response to ongoing budgetary chaos at the legendary La Cañada Flintridge facility.

The layoffs reduced the employee headcount by more than 10% and affected teams across the institution, according to multiple sources not authorized to speak publicly.

A reorganization for remaining staffers will be announced on Wednesday.

“This week’s action, while not easy, is essential to securing JPL’s future by creating a leaner infrastructure, focusing on our core technical capabilities, maintaining fiscal discipline, and positioning us to compete in the evolving space ecosystem,” JPL Director Dave Gallagher said in a statement Monday.

The cuts were part of a reorganization that began in July, he said, and are not related to the federal government shutdown that began on Oct. 1.

JPL staffers are employed by Caltech, and none have been furloughed since the standoff between Democrats and Republicans in Congress began. But the research facility started preparing for a leaner future even before President Trump took office, and is enduring one of the most challenging stretches in its nearly 89-year history.

“The morale has been as low as anyone has seen in decades, maybe ever,” an employee spared by the layoffs said. “The uncertainty is very unsettling. … We expect more people will leave in the coming months due to continued uncertainty on the type of work that may or may not come.”

Layoffs and attrition have reduced JPL’s overall staffing by about one-third in the last two years, sources at the organization said, from roughly 6,500 to around 4,500 after this week’s reduction. JPL endured three rounds of layoffs last year alone, prompted by massive federal budget cuts for its beleaguered Mars Sample Return mission.

The Eaton fire came perilously close to the campus in January, forcing some 20% of the agency’s workforce to evacuate their homes. About 210 employees lost their homes in the fire, and dozens more were displaced for months.

Then in May, the Trump administration proposed a $6-billion cut from NASA’s $24.8-billion budget for the coming fiscal year, a 24% drop from its current allocation.

While both the House and Senate appropriations committees would largely keep the agency’s overall funding intact, their budgets reallocate money within the space agency in ways that could profoundly affect JPL’s work.

The House appropriations bill would keep NASA’s funding steady but cut about $1.3 billion from NASA’s $7.3 billion Science Mission Directorate, which funds many of the missions that JPL manages. The Senate bill, in contrast, would maintain the science program’s funding.

It’s not yet clear how the most recent layoffs will affect JPL’s work on drought, fire and climate change. No missions have yet been canceled or paused. But with no end in sight to the stalemate, JPL’s future remains in limbo.

“JPL is a national asset that has helped the United States accomplish some of the greatest feats in space and science for decades,” Rep. Judy Chu (D-Monterey Park) said. “Taken together with last year’s layoffs, this will result in an untold loss of scientific knowledge and expertise that threatens the very future of American leadership in space exploration and scientific discovery.”

Times staff writer Hayley Smith contributed to this report.

Science

The key health bills California Gov. Newsom signed this week focused on how technology is impacting kids

New laws signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom aim to make the artificial intelligence and social media landscape in California safer, especially for minors.

Senate Bill 243, sponsored by state Sen. Steve Padilla (D-Chula Vista) will require AI companies to incorporate guardrails that prevent so-called “companion” chatbots from talking to users of any age about suicide or self-harm. It also requires that all AI systems alert minors using the chatbots that they are not human every three hours. The systems also are barred from promoting any sexually explicit conduct to users who are minors.

The law, to be enacted on Jan. 1, follows several lawsuits filed against developers in which families allege their children committed suicide after being influenced by an AI chatbot companion.

In the same vein, Newsom signed Assembly Bill 316, which removes a civil legal defense that some AI developers have been using to make the case that they are not responsible for any harm caused by their products. They have argued that their AI products act autonomously — and so there is no legal case to blame the developers.

In a bill analysis meant for legislators, Assemblymember Maggy Krell (D-Sacramento) wrote that this change will force developers to vet their product better and ensure that they can be held to account if their product does cause harm to its users.

Another bill, AB 621, increases civil penalties for AI developers who knowingly create nonconsensual “deepfake” AI pornography. The maximum penalties go from $30,000 to $50,000, and from $150,000 to $250,000 in cases where the courts determine that the actions were done with malice.

The author of the bill, Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan (D-Orinda), has pointed out how this technology has been used to harm minors. “In one recent instance,” she noted in an analysis supporting the proposed legislation, “five students were expelled from a Beverly Hills Middle School after creating and sharing AI generated nude photos of their classmates.”

Another AI bill, Sen. Scott Wiener’s (D-San Francisco) SB 53, was signed into law by Newsom in late September. It will require large AI companies to publicly disclose certain safety and security protocols and report to the state on critical safety incidents. It also creates a public AI computing cluster — CalCompute — that will provide resources to startups and researchers developing large AI systems.

Bauer-Kahan also was the author of AB 56, which will require social media companies to place a warning label on their platforms for minors starting in 2027. The warning label must tell children and teens that social media is associated with mental health issues and may not be safe.

“People across the nation — including myself — have become increasingly concerned with Big Tech’s failure to protect children who interact with its products. Today, California makes clear that we will not sit and wait for companies to decide to prioritize children’s well-being over their profits,” Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta, who sponsored the bill, said in a news release. “By adding warning labels to social media platforms, AB 56 gives California a new tool to protect our children.”

Other bills recently approved by Newsom look to challenge the Internet’s grip on young people and their mental health.

AB 1043, for example, will require app stores and device manufacturers to take age data from users in order to ensure that they are complying with age verification requirements. Many tech companies, including Google and Meta, approved of the bill, which was written by Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland).

AB 772 will require grade K-12 schools in the state to develop a policy by mid-2027 on handling bullying and cyberbullying that happens off campus. “After-school bullying follows the pupil back to school and into the classroom, creating a hostile environment at school,” author and Assembly Speaker Pro Tem Josh Lowenthal (D-Long Beach) wrote in a bill analysis.

Proponents at the Los Angeles County Office of Education wrote in an earlier analysis that because students these days are constantly connected to the internet, bullying does not stop when school lets out. In addition, social media and texting can broadcast instances of bullying to larger audiences than ever before, according to the analysis.

The California School Boards Assn. opposed AB 772, saying that it wasn’t appropriate for school officials to take responsibility for student actions outside of school. Newsom signed the bill last weekend and included it in a larger package of bills meant to protect children from the effects of social media.

“Emerging technology like chatbots and social media can inspire, educate, and connect — but without real guardrails, technology can also exploit, mislead and endanger our kids. We’ve seen some truly horrific and tragic examples of young people harmed by unregulated tech, and we won’t stand by while companies continue without necessary limits and accountability,” Newsom said in a news release Monday. “We can continue to lead in AI and technology, but we must do it responsibly — protecting our children every step of the way. Our children’s safety is not for sale.”

Science

Man, machine and mutton: Inside the plan to prevent the next SoCal fire disaster

Nine months after one of the worst fires the region has seen in recorded history, a helicopter carrying two of the most consequential politicians in the fight against Southern California’s wildfires soared over the Santa Monica Mountains. Rows of jagged peaks slowly revealed steep canyons. The land was blotchy: some parts were covered in thick, green and shrubby native chaparral plants; others were blackened, comprised mostly by fire-stricken earth where chaparral used to thrive; and still others were blanketed by bone-dry golden grasses where the land had years ago been choked out by fire.

Amid this tapestry was a scattering of homes and businesses with only a handful of roads snaking out: Topanga. The dangers, should a fire roar down the canyon, were painfully clear at a thousand feet.

“If there are any issues on the Boulevard…” County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath said into her headset, trailing off.

“The community is trapped,” said Wade Crowfoot, California Secretary for Natural Resources, finishing the thought.

Over the same mountains where the Palisades fire roared, the supervisor and secretary were observing the state’s nearly 675-acre flagship project to stop the Santa Monica Mountains’ next firestorm from devouring homes and killing residents.

Crews from the Los Angeles County Fire Department and the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, a local land management agency, were cutting a miles-long web of fuel breaks in the Northern Santa Monicas between Topanga and Calabasas. In the spring, they hope to perform a prescribed burn along the break. Just northwest, on the other side of Calabasas, Ventura County Fire Department deployed 500 goats and 100 sheep to eat acres of invasive grasses that are prone to conflagration.

A fire crew walks in the Santa Monica Mountains during a wildfire risk reduction project on Oct. 8.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

It’s just a fraction of the work state leaders and local fire crews hope to someday accomplish, yet the scale and speed of the effort has already made some ecology and fire experts uneasy.

(The goats, however, have enjoyed virtually universal praise.)

While many firefighters and fire officials support the creation of fuel breaks, which offer better access to remote areas during a fire fight, fire ecologists warn that if not done carefully, fuel breaks can make the landscape even more fire-prone by inadvertently replacing chaparral with flammable invasive grasses.

Yet, after the Palisades fire last January, many state leaders and residents in the Santa Monicas feel it’s better to act now — even if the plan is a bit experimental — given the mountains will almost certainly burn again, and likely soon.

Goats help clear vegetation in the Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve as part of a wildfire risk reduction project.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

In March, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order streamlining the approval process for these projects. Instead of seeking multiple permits through separate lengthy processes — via the California Environmental Quality Act, Coastal Act, Endangered Species Act, and Native Plant Protection Act (among others) — applicants can now submit projects directly to the California Natural Resources Agency and California Environmental Protection Agency, which ensures compliance with all of the relevant laws.

Consequently, the state has approved well over 100 projects in mere months. Before, it was not uncommon for projects to sit in limbo for years awaiting various approvals.

In April, the state legislature and Newsom approved the early release of funds from a $10 billion climate bond that California voters approved last November for these types of projects. The Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, which received over $31 million of that funding, awarded just over $3 million to L.A. County and Ventura County fire departments and the MRCA to complete the project.

On Oct. 8, Horvath and Crowfoot watched from a ridgeline northwest of Topanga as crews below maneuvered a remote-controlled machine — named the Green Climber after its color and ability to navigate steep slopes — to chew up shrubs on the hillsides. Others used a claw affixed to the arm of a bright-red excavator to rip out plants.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath flies over the Malibu coastline during a tour of a wildfire risk reduction project in the Santa Monica Mountains.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

The goal was to create a new fuel break on a plot of land that is one of the few areas in the Santa Monicas that hasn’t burned in the last seven years, said Drew Smith, assistant fire chief with the L.A. County Fire Department. “Going into the fall, our biggest vulnerabilities are all this right here.”

Left alone, chaparral typically burns every 30 to 130 years, historically due to lightning strikes. But as Westerners began to settle the region, fires became more frequent. For example, Malibu Canyon — which last burned in the Franklin fire, just a month before the Palisades fire — now experiences fire roughly every eight years.

As the fire frequency chokes out the native chaparral ecosystem, fast growing, extremely flammable invasive grasses take over, making it even more likely that a loose cigarette or downed power line will ignite a devastating blaze. Scientists call this death spiral the human-grass-fire cycle. Stopping it is no simple task. And reversing it, some experts fear, may be borderline impossible.

The state’s current approach, laid out by a panel of independent scientists working with California’s wildfire task force, is three-pronged.

First: home hardening, defensible space and evacuation planning to ensure that if a monster fire starts, it causes the smallest amount of death and destruction.

Second: Techniques to prevent fire ignitions in the first place, such as deploying arson watch teams on high-wind days.

Third: Creating a network of fuel breaks.

Fuel breaks are the most hotly debated, in part because fuel breaks alone do little to stop a wind-driven fire throwing embers miles away.

But fire officials who have relied on fuel breaks during disasters argue that such fuel breaks can still play “a significant tactical role,” said Smith, allowing crews to reach the fire — or a new spot fire ignited by an ember — before it blows through a community.

A Los Angeles County Fire Department excavator with a claw grapple clears vegetation in the Santa Monica Mountains.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

But Dan Cooper, principal conservation biologist with the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains, said there’s little scientific evidence yet that indicates fuel breaks are effective.

And because creating fuel breaks harms ecosystems and, at worst, can make them even more fire prone, fire ecologists warn they need to be deployed strategically. As such, the speed at which the state is approving projects, they say, is concerning.

Alexandra Syphard, senior research scientist at the Conservation Biology Institute and a leading Southern California fire ecologist, noted that the fuel break the Santa Monica Mountains team is creating near Topanga seems to cut right through healthy chaparral. If the fire crews do not routinely maintain the fuel break, it will be flammable golden grasses that grow back, not more ignition-resistant chaparral.

A remote controlled masticator — called the “Green Climber” — mulches flammable vegetation in Topanga to keep flames at a low height.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

And the choices land managers make today can have significant consequences down the line: While fire crews and local conservationists are experimenting with how to restore chaparral to grass-filled areas, in the studies Syphard has looked at, once chaparral is gone, it seldom comes back.

For Cooper, the trade-offs of wildfire risk reduction get at a fundamental tension of living in the Santa Monicas. People move to places like Topanga, in part, because they love the chaparral-dotted vistas, the backyard oak woodlands and the privacy of life in the canyon. Yet, it’s that same environment that imperils them.

“What are you going to do about it? Pave the Santa Monicas? A lot of the old fire guys want to make everything grass in the Santa Monicas because grass fires are just easier to put out,” he said. “We need to learn how to live with fire — in a lot more sober way.”

-

Augusta, GA5 days ago

Augusta, GA5 days ago‘Boom! Blew up right there’: Train slams into semi in Grovetown

-

Wisconsin7 days ago

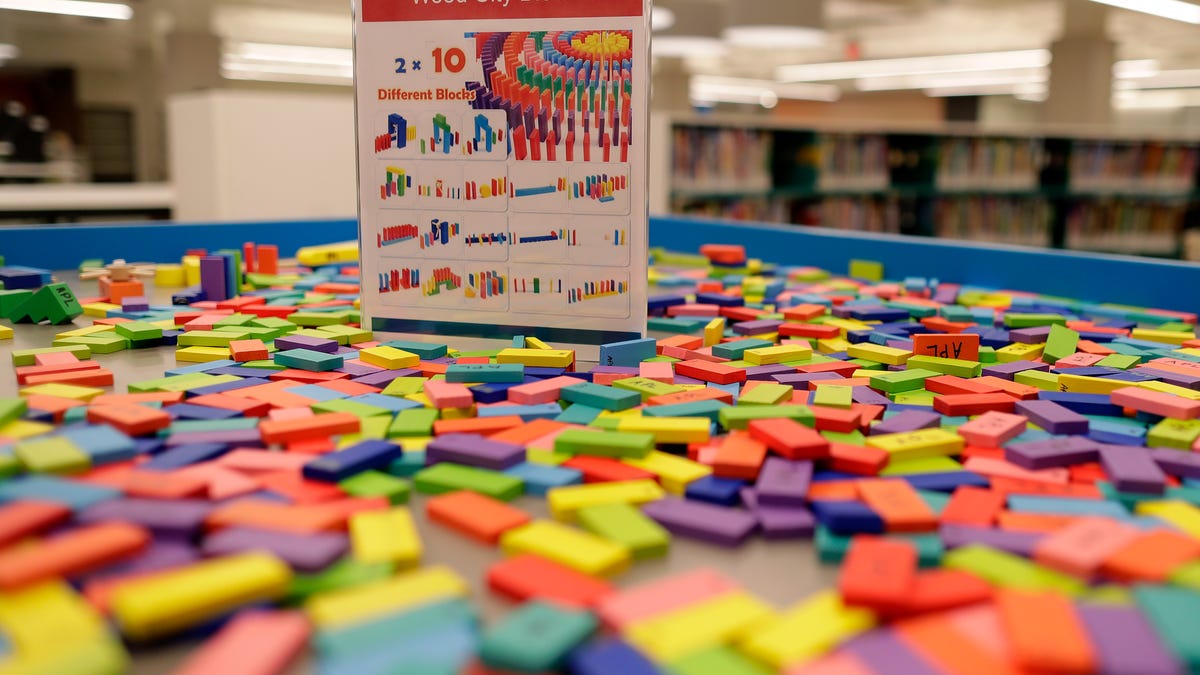

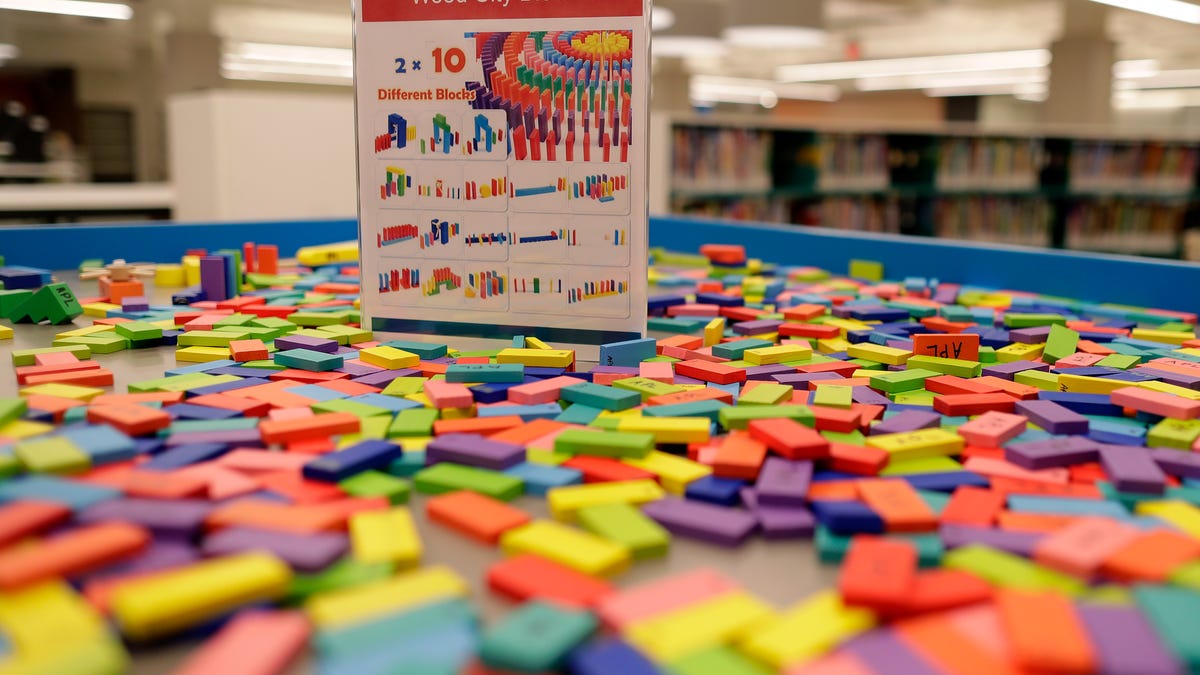

Wisconsin7 days agoAppleton Public Library wins 2025 Wisconsin Library of the Year award for distinguished service

-

Business6 days ago

Los Angeles Times Media Group takes step to go public

-

Virginia7 days ago

Match 13 Preview: #8 Virginia

-

Vermont7 days ago

Vermont7 days agoFeds: Springfield dealer ran his drug business from Vermont jail

-

West Virginia1 week ago

West Virginia1 week agoWest Virginia eatery among Yelp’s “outrageous outdoor dining spots”

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWhat we know about the charges against New York’s Attorney General Letitia James

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoSpanberger refuses to urge Jay Jones to exit race, dodges questions after ‘two bullets’ texts