New York

The Polygon and the Avalanche: How the Gilgo Beach Suspect Was Found

They called it the polygon.

Using phone records and a sophisticated system that maps the reach of cell towers, a team of investigators had drawn the irregular shape across a map of tree-lined streets in the Long Island suburb of Massapequa Park. By 2021, the investigators had been able to shrink the polygon so that it covered only several hundred homes.

In one of those homes, the investigators believed, lived a serial killer.

A decade before, 11 bodies had been found in the underbrush around Gilgo Beach, a remote stretch of sand five miles away on the South Shore. Four women had been bound with tape or belts or wrapped in shrouds of camouflage-patterned burlap, the sort that hunters use for blinds. They had worked as escorts and had gone missing after going to meet a client.

Each, shortly before she disappeared, had been in contact with a different disposable cellphone. Investigators eventually determined that during the workday, some of the phones had been in a small area of Midtown Manhattan near Penn Station, and at night they pinged in the polygon, mirroring the tidal movements of the 150,000 Long Island residents who head into Manhattan each day.

Last Friday, Suffolk County authorities announced that they had arrested a man who they believed had killed the four women: Rex Heuermann, a 59-year-old architect who had an office near Penn Station and lived on a quiet street right where they had expected to find him. He was charged with three of the murders, to which he has pleaded not guilty, and was named as the prime suspect in the fourth.

The arrest ended years of anguish for some of the victims’ families. But the investigation also raised an unsettling question: Could the authorities have solved the case years earlier?

The following account is drawn from a 32-page bail application and interviews with current and former investigators and Suffolk County’s top law enforcement officials.

The case had unfolded fitfully over more than a decade. But it took a new police commissioner and his task force just six weeks to uncover a crucial clue in the sprawling case file.

Working under Commissioner Rodney K. Harrison, the core group of about 10 investigators was drawn from his department, the sheriff’s office, F.B.I. and State Police and worked closely with District Attorney Ray Tierney of Suffolk County and his prosecutors.

They worked in a beige office, its walls covered with maps, photos and a giant timeline, scouring their suspect’s digital and daily life — email addresses, social media accounts, search history.

All the while, Mr. Heuermann was searching, too, asking Google the same question that so many of his neighbors had been asking each other for more than a decade: “why hasn’t the long island serial killer been caught?”

Grim Discoveries

Picking up the trail of a serial killer is an exceptional challenge. The killer often has no personal connection to the victims. If the victims lived on society’s margins, months or years can go by before their disappearances are treated as serious matters — or even recognized as the work of a single murderer.

The realization that a serial killer was hunting on Long Island’s South Shore came in December 2010, when a Suffolk County police officer, John Mallia, and his canine partner, a German shepherd named Blue, were searching for a 24-year-old woman named Shannan Gilbert, who had gone missing in the area.

Instead, over several days they found four other bodies near Gilgo Beach. They had been placed roughly 10 yards from Ocean Parkway, the main east-west thoroughfare that traverses a barrier island off the South Shore. After they discovered the bodies, investigators searched for evidence nearby with meticulous care — “sifting the sand like gold miners around each body,” one investigator recalled.

Ms. Gilbert’s corpse and other remains, including those that the authorities described as a man wearing women’s clothing and a toddler, would be found along the same roadway over the following year. The grisly discoveries riveted the region as the police speculated that the killings might be the work of more than one person.

But the first four bodies — all petite women in their 20s who had gone missing in the previous four years — seemed linked. Investigators surmised they had been killed by the same man, in part because of the way the bodies were wrapped and their proximity. And there was reason to believe that a witness might have gotten a look at the man.

The last of the four to disappear had been Amber Costello, a 27-year-old with a “Kaos” tattoo on her neck who advertised on Backpage and Craigslist. Shortly before she was last seen in September 2010, a would-be client contacted her from a disposable cellphone and visited her at the West Babylon house she shared with three roommates, parking in her driveway, according to court papers filed after Mr. Heuermann’s arrest. He drove a vehicle with a distinctive look: SUV in the front, pickup in the back.

The driver was just as distinctive: hulking, in his 40s, with bushy dark hair and 1970s-style eyeglasses. A witness described him as an ogre.

But as soon as the would-be client paid Ms. Costello, a chaotic scene unfolded. A man “pretending to be the outraged boyfriend” rushed in, part of a ruse to steal the money, according to the court papers.

Startled, the hulking man rushed out of the house.

He did not disappear for long, though. He texted Ms. Costello asking for “credit for next time” and arranged another meeting, according to the court papers. Ms. Costello was last seen alive the next night walking out of her home, apparently to meet the man.

Not long after, a witness reported seeing a dark truck drive by.

The description of the vehicle in the driveway, a dark, first-generation Chevrolet Avalanche, ended up tucked away in the case file, the authorities said.

Sifting the Signals

The fact apparently lay buried for years among hundreds of thousands of pages of interviews; telephone, travel and credit records; and endless tips as the Suffolk County police department and district attorney’s office endured years of turmoil.

James Burke, the swaggering police chief who had been running the department since 2012, was arrested in 2015 and later convicted on federal civil rights and obstruction of justice charges. He had beaten a suspect who had been arrested after stealing cigars and a bag containing pornography and sex toys from Mr. Burke’s sport utility vehicle. The subsequent cover-up ensnared the district attorney at the time, Thomas J. Spota, who also landed in prison.

The federal investigation into Suffolk County’s top lawmen spanned years during the Gilgo Beach case, a period during which both Mr. Burke and Mr. Spota had spurned help from the F.B.I.

After Mr. Burke’s arrest, the new head of the Suffolk County police, Tim Sini, redoubled the department’s efforts. Mr. Sini, a former Manhattan federal prosecutor, focused on tracking the disposable cellphones, hoping there were more clues to be gleaned.

F.B.I. agents in 2012 had already identified the area where coverage from four cell towers overlapped in Massapequa Park. By mid-2016, Mr. Sini had secured a court order for “tower dumps” — information on every phone that connected to particular towers in a given window of time.

Technology and software had advanced. And Mr. Sini had invested in a system that allowed investigators to “take the relevant areas,” as he told Newsday, and “shrink them to extremely manageable spaces.”

They whittled down the area to what they came to call the polygon, which left them with several hundred homes around First Avenue in Massapequa Park, law enforcement officials said.

A pattern emerged from the disposable phones used to contact the victims: In the evening, nighttime and predawn hours, some were in a small area of Massapequa Park, a person with knowledge of the investigation said. That’s also where the phone of one victim, Megan Waterman, was last logged at 3:11 a.m. on June 6, 2010, shortly before she disappeared, according to court papers.

During the day, the phones were used in Midtown Manhattan.

Among other communications that investigators scrutinized were sadistic, taunting calls someone made from the cellphone of one victim, Melissa Barthelemy, to her teenage sister shortly after she had disappeared in 2009. “Do you think you’ll ever speak to her again?” the person had asked in a bland, calm voice.

Those calls were also linked to cell towers near Penn Station, the court papers said.

For years, investigators looked for suspects who worked in Manhattan and had lived in the polygon. The going was slow, and though investigators expressed optimism they would find their man, they had little to show.

Suddenly, a Suspect

The big break came in March 2022.

Just weeks after the formation of the task force, an investigator found the witness’s description of the Chevrolet Avalanche in the case file, authorities said. Using a database that can search for vehicles by make and model without license-plate numbers, the investigator found an Avalanche linked to Mr. Heuermann in 2010, the year Ms. Costello went missing.

His name had never come up in the investigation as a suspect, officials said. His physical description matched that of the ogreish man who had rushed out of her house shortly before she disappeared: He was 6-foot-4 and heavyset. His office was in the patch of Manhattan identified by the sophisticated cellphone mapping.

And he lived in what investigators believed was their serial killer sweet spot: the part of Massapequa Park where they had begun drawing their polygon.

The Avalanche lead, said Mr. Tierney, the district attorney, had been “known pretty much from the beginning.” Mr. Tierney, who took office in 2022, said he did not know why investigators had not pursued it. He suggested that perhaps the detail hadn’t been deemed credible or had sunk in significance amid what seemed like more promising leads.

“There are piles of evidence,” he said. “What is credible, what’s not, what seems likely, what’s not — so it’s not as simple as it seems.”

But crimes are often solved by tracking down a vehicle, and cases often start with a car description. David Berkowitz, known as Son of Sam and perhaps the state’s most notorious serial killer, was arrested in the 1970s after the police found that he owned an illegally parked Ford Galaxie that had received a parking ticket near one of the shootings.

In the Gilgo Beach investigation, the critical clue had fallen through the cracks.

“If they knew about it then, a major mistake was made in not tracking down this car earlier,” said Rob Trotta, a former Suffolk County detective and a current county legislator, who said he expects to make an official inquiry into what happened.

Dominick Varrone, the former chief of detectives who oversaw the first year of the investigation, questioned whether the Avalanche clue had actually been in the case file, but added, “I will feel very, very badly if our team missed something.”

“I’ll tell you right now: No suspect vehicle was on our radar when I was still there,” he added.

When investigators did finally link the Chevrolet Avalanche to Mr. Heuermann, the investigation entered its critical phase. Investigators began exploring every aspect of his life, using 300 subpoenas and search warrants.

They examined his Tinder account and several email addresses — all fictitious names — that led to additional disposable phones that Mr. Heuermann was using to contact massage parlors and women working as escorts, the court papers said. They found internet searches for child pornography.

The more investigators learned about Mr. Heuermann, the more convinced they were.

So much time had passed since the killings that precise locational data from Mr. Heuermann’s personal cellphone — registered to his architectural business — no longer existed. But his billing records showed the general location of the phone when calls were made, the court papers said, putting it in New York City around the same time in 2010 that the cruel and taunting calls were made on Ms. Barthelemy’s cellphone.

Investigators learned that several of the murders had occurred when Mr. Heuermann’s wife and children were out of town, according to prosecutors. One coincided with a trip his wife took to Iceland; another took place when she was in Maryland and a third when she was in New Jersey.

But they had nothing to put the burner phones that had been in contact with the victims in Mr. Heuermann’s hands.

Nor did they have any physical or forensic evidence directly linking him to the crimes.

That would soon change.

The Tipping Point

In the investigation’s early days, at least five hairs were discovered on the victims or stuck to the burlap or duct tape that enveloped them. They were deemed unsuitable for detailed DNA analysis.

Forensic science moved ahead: In the past three years, two outside laboratories were able to generate thorough DNA reports, according to court papers.

Now, investigators needed genetic material from Mr. Heuermann. Last July, an undercover detective rooted through his recycling for empty bottles. In January, Mr. Heuermann tossed a pizza box into a sidewalk garbage can outside his office in Midtown. A surveillance team fished it out, and the ragged crusts inside gave them what they needed.

Investigators concluded that most of the hairs found on the victims were likely to have come from Mr. Heuermann’s wife. One was a potential match for Mr. Heuermann himself.

One laboratory compared the DNA profile from the fifth hair to the genetic material found on Mr. Heuermann’s pizza. It found enough markers in common to conclude that while 99.96 percent of the population could be excluded as a match, Mr. Heuermann could not, the authorities said.

Mr. Tierney learned of the results in June.

He read the report again and again — perhaps dozens of times, as if trying to convince his brain of what his eyes were seeing.

Investigators believed they now had direct evidence linking Mr. Heuermann to the killings.

But investigators knew something else: Mr. Heuermann was scouring the internet for information about what they were doing.

Internet searches linked to his anonymous accounts included more than 200 queries in the past 16 months about serial killers generally and the investigation into the Gilgo Beach victims specifically. “Why could law enforcement not trace the calls made by the long island serial killer” was just one.

Mr. Tierney had grown increasingly worried that more victims would drop on his watch. He said that Mr. Heuermann had been visiting massage parlors — and contacting women working as escorts.

Mr. Tierney said he was sleeping badly, bedeviled by tension and worry. Last week, he decided the case had reached a tipping point.

So on the evening of July 13, detectives in suits and ties approached Mr. Heuermann after he walked out of his office building.

Mr. Heuermann, prosecutors said, had methodically covered his tracks and closely monitored the investigation.

But when the detectives arrested Mr. Heuermann after more than a dozen years of pursuit, Mr. Tierney said, his reaction was simple and instinctive: genuine surprise.

New York

Read the Justice Department’s Epstein Filing

Case 1:19-cr-00490-RMB Document 61 Filed 07/18/25

Page 3 of 4

4.

“It is a tradition of law that proceedings before a grand jury shall generally remain secret.” In re Biaggi, 478 F.2d 489 (2d Cir. 1973). “[T]he tradition of secrecy,” however, “is not absolute.” In re Petition of Nat. Sec. Archive, 104 F. Supp. 3d 625, 628 (S.D.N.Y. 2015). Although Rule 6(b)(3) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure generally lists the exceptions to grand jury secrecy, the Second Circuit has recognized that “there are certain ‘special circumstances’ in which release of grand jury records is appropriate even outside the boundaries of the rule.” In re Craig, 131 F.3d 99, 102 (2d Cir. 1997); see also Carlson v. United States, 837 F.3d 753, 767 (7th Cir. 2016) (“Rule 6(e)(3)(E) does not displace that inherent power. It merely identifies a permissive list of situations where that power can be used.”). One such “special circumstance” is historical interest by the public. In re Craig, 131 F.3d at 105. Under In re Craig, this Court retains discretion to determine “whether such an interest outweighs the countervailing interests in privacy and secrecy[.]” Id.

5.

Public officials, lawmakers, pundits, and ordinary citizens remain deeply interested and concerned about the Epstein matter. Indeed, other jurists have released grand jury transcripts after concluding that Epstein’s case qualifies as a matter of public concern. See Order Granting Plaintiff’s Motion for Reconsideration of the Trial Court’s February 29, 2024 Order, CA Florida Holdings, LLC v. Dave Aronberg and Joseph Abruzzo, 50-2019 CA-014681 (15th Cir. July 1, 2024).³ After all, Jeffrey Epstein is “the most infamous pedophile in American history.” Id. The facts surrounding Epstein’s case “tell a tale of national disgrace.” In re Wild, 994 F.3d 1244, 1247 (11th Cir. 2021) (discussing the plea agreement secured by Epstein in Florida). The grand jury records are thus “critical pieces of an important moment in our nation’s history.” In re Petition of Nat. Sec. Archive, 104 F. Supp. 3d at 629. “The time for the public to guess what they contain

3 https://www.mypalmbeachclerk.com/home/showpublisheddocument/4194/638554423710170000.

3

New York

Read Thomas Donlon’s Lawsuit

New York

Video: Inside Rikers Island: A Suicide Attempt as Guards Stand By

This is the inside of a psychiatric unit on Rikers Island. It’s the morning of Aug. 25, 2022. And soon, this inmate, Michael Nieves, will attempt to commit suicide by cutting his own throat. He’ll bleed out for 10 minutes as officers stand by and wait for medical help. But Michael Nieves is just one of many cases of preventable harm on Rikers Island that ultimately led a federal judge to strip control of the jail from the City of New York in May. Soon, an independent manager will be appointed. After almost three years of filing Freedom of Information requests and lawsuits, The New York Times has now obtained videos of incidents that contributed to this decision, including that of Nieves. They take us inside Rikers, a place rarely seen by the public, and show serious lapses in the care of inmates. A long-serving member of an independent oversight body, who we’ll hear from later, told us that the case of Michael Nieves is characteristic of the problems inside the jail. Here’s what happened. It’s around 11:30 a.m., and a search of Michael Nieves’s cell fails to turn up a shaving razor he was given to use in the shower that morning. Capt. Mary Tinsley, the supervisor in charge, instructs Officer Beethoven Joseph, whose body camera footage we see here, to take Nieves for a body scan to see if he is hiding the razor. But Tinsley grows impatient with Nieves. Officers close the door and walk away. This is one of a series of mistakes that play out. These officers are trained to work with severely mentally ill detainees like Nieves, a once-gifted student who was later diagnosed with bipolar and schizophrenia disorders. Like most inmates on Rikers, Nieves was awaiting trial and had not yet been convicted of a crime. He was arrested on burglary and arson charges in 2019, but was deemed unfit to stand trial and held in forensic psychiatric facilities before being sent back to Rikers. Nieves had a long history of suicide attempts. And even though officers suspect he has the razor, he is left alone for 12 minutes while they search the cell of another inmate. Then Joseph returns, followed by Tinsley. She radios for help. The scene is disturbing, but we’re showing it briefly to illustrate what the officers could see. Nieves has cut his neck and is bleeding heavily onto the floor. Pressure needs to be applied to the wound immediately, and he needs to get to a hospital. At first, Nieves doesn’t respond. And the officers and Captain Tinsley don’t intervene. Officer Joseph faces a complex situation. Jail guidelines do not clearly say he should treat a severely bleeding wound. And officers are advised to use caution when they might be lured into danger. But state law does require him to render care in life-threatening situations. It’s unclear if he recognizes it as such. No one enters the cell. Instead, they offer Nieves a piece of clothing. Five minutes have passed. Officer Joseph asks about the bleeding. Eight minutes have passed. Nieves slides down to the floor. Officer Joseph shows concern, but remains by the door. After 10 minutes, the medics arrive on the ward and enter the cell. But there’s been a communication breakdown. The medics aren’t aware that Nieves is bleeding profusely, and they don’t have the right supplies. As they spring into action, the medics berate the correction officers. As medics render aid, Officer Joseph goes to review his notes and talks with another staff member. About an hour after Nieves was found bleeding, over a dozen medics, staff, and E.M.T.s are treating him on site. Shortly after, he was taken to a nearby hospital, declared brain dead and removed from life support five days later. “This was preventable.” Dr. Robert Cohen is a member of the Board of Correction, which monitors Rikers, and agreed to speak about the jail and the Nieves case in a personal capacity, not on behalf of the board. He retired shortly after this interview. “He should not have been left alone once they believed that he was in possession of a razor. By policy, he should have been taken immediately to the body scanner.” “He was bleeding to death. The correction officer should have gone into the room, assessed what was going on and should have applied pressure to the area where the blood was coming from.” A city medical examiner found that the officer’s inaction contributed to Nieves’s death, but that he could have died even with emergency aid. The state attorney general’s office therefore declined to charge the officers. Their report also found that the officers lacked clear protocols and might not have had training on severely bleeding wounds. It recommended that officers be required and trained to act in these situations in the future. Dr. Cohen says that what happened to Nieves is characteristic of chronic problems inside Rikers. “Since I’ve been on the board, these deaths have happened multiple times. Jason Echevarria swallowed a number of soap balls. He was screaming all night long. Jerome Murdough was put in a cell where there was a heating malfunction, baked to death. Mercado had diabetes. He was trying to get help. He never received insulin. Nicholas Feliciano hung himself. Seven officers were completely aware of this, and they did nothing — 7 minutes and 51 seconds passed. He did not die, but he has severe brain damage.” Nieves’s death occurred two years into the Covid pandemic, a time when Rikers was facing acute challenges and a staffing crisis that watchdogs say led to a spike in preventable deaths. “Many deaths over the past five years and the reports of deteriorating conditions were instrumental in moving us to the point right now where the judge is going to take over the island with an independent manager.” But even after that happens, New York’s next mayor will be tasked with trying to close Rikers. The original plan was to replace it with smaller jails and in four New York City boroughs by 2026. But after years of delays, here’s what those sites look like today. They’re nowhere near done. Oversight bodies, and even the former Manhattan U.S. attorney, have said that Rikers remains unsafe for detainees. The Department of Correction told The Times that a new medical emergencies curriculum is still being developed. A spokesperson for the Correction Officers Union said they followed regulations and have been vindicated. And the Captain’s Union, which represented Captain Tinsley, said she also followed protocol. Nieves was one of three brothers. His family is now suing the city.

-

Iowa1 week ago

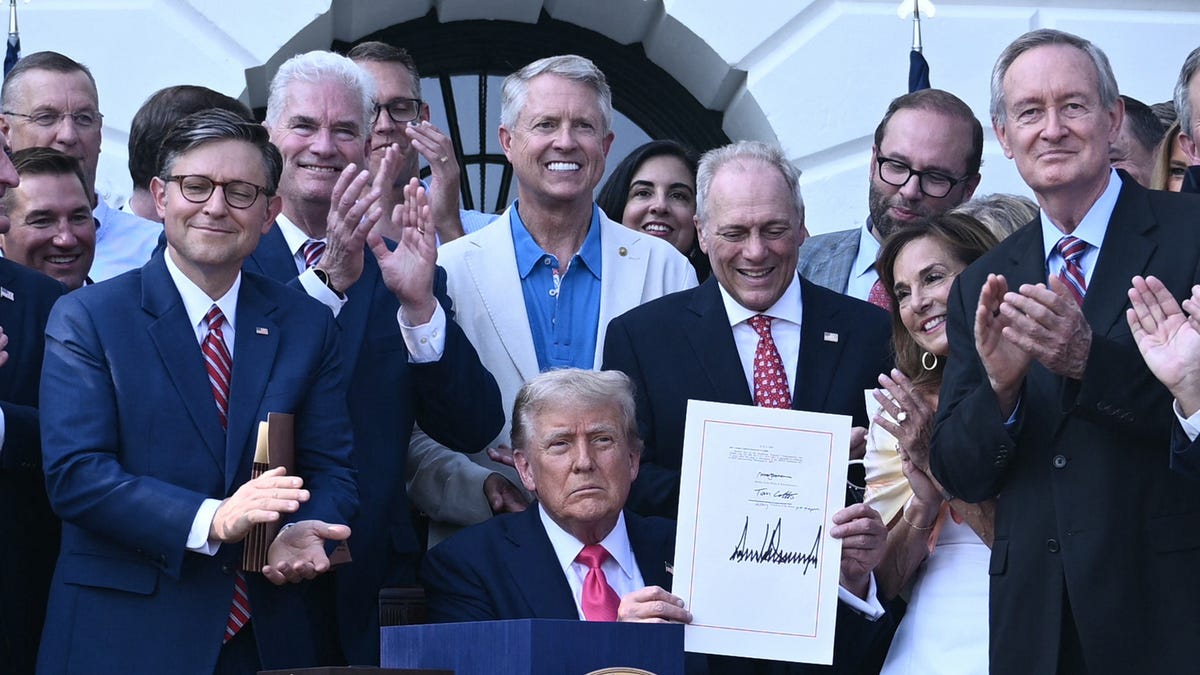

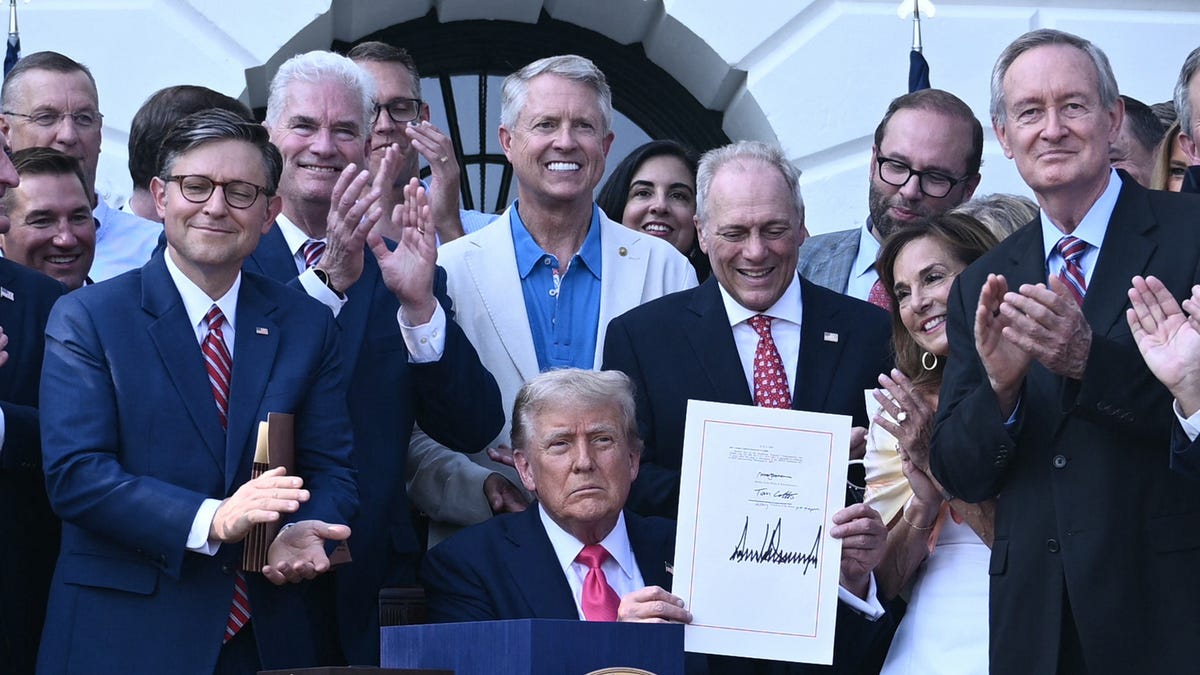

Iowa1 week ago8 ways Trump’s ‘Big, Beautiful Bill’ will affect Iowans, from rural hospitals to biofuels

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoConstitutional scholar uses Biden autopen to flip Dems’ ‘democracy’ script against them: ‘Scandal’

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDOJ rejects Ghislaine Maxwell’s appeal in SCOTUS response

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoNew weekly injection for Parkinson's could replace daily pill for millions, study suggests

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSCOTUS allows dismantling of Education Dept. And, Trump threatens Russia with tariffs

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTest Your Knowledge of French Novels Made Into Musicals and Movies

-

Business1 week ago

Musk says he will seek shareholder approval for Tesla investment in xAI

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoEx-MLB pitcher Dan Serafini found guilty of murdering father-in-law