New York

Decades Ago, Columbia Refused to Pay Trump $400 Million. Note That Number.

Donald Trump was demanding $400 million from Columbia University.

When he did not get his way, he stormed out of a meeting with university trustees and later publicly castigated the university president as “a dummy” and “a total moron.”

That drama dates back 25 years.

Today, these two New York City institutions — the ostentatious billionaire president of the United States and the 270-year-old Ivy League university that has cultivated 87 Nobel laureates — are locked in an extraordinary clash. The future of higher education and academic freedom dangle in the balance.

But the first battle between Mr. Trump and Columbia involved the most New York of New York prizes — a lucrative real estate deal, according to interviews with 17 real estate investors and former university administrators and insiders, as well as contemporaneous news articles.

Some former university officials are quietly wondering whether the ultimately unsuccessful property transaction sowed the seeds of Mr. Trump’s current focus on Columbia. His administration has demanded that the university turn over vast control of its policies and even curricular decisions in its effort to quell antisemitism on campus. It has also canceled federal grants and contracts at Columbia — valued at $400 million.

The Trump Organization and the White House declined to comment.

Lee C. Bollinger, the former president of Columbia who eventually opted not to pursue the property owned by Mr. Trump and foreign investors, chose instead to expand the Columbia campus on land adjacent to the university. “I wanted for Columbia a much more ambitious project than the Trump property would permit, and one that would fit with the surrounding properties, that would blend in with the Morningside campus and the Harlem community,” he said in an interview.

The clash had its roots in the late 1990s, when Columbia was facing a common challenge in New York: Situated in one of the most expensive and congested cities in the world, it wanted more space. The federal government was supercharging the budget of the National Institutes of Health, and to compete with other universities for research grants, Columbia needed room to house more scientists and labs.

Expanding its footprint beyond its Morningside Heights campus into neighboring Harlem would be complicated. In 1968, the university began construction on a gymnasium in Morningside Park. The design, construction delays and limited access to Harlem residents resulted in “cries of segregation and racism,” according to a Columbia University Libraries exhibit. Tension between the university and community leaders in Harlem persisted for decades.

Columbia officials and trustees hoped to mend the relationship, but they knew they also needed to look for alternatives.

Enter Mr. Trump. Not yet a reality television star, he was then a brash real estate developer, with a love of tabloid press attention. He offered a home for a Columbia expansion, an undeveloped property on the Upper West Side between Lincoln Center and the Hudson River. It was known as Riverside South before he rebranded it Trump Place.

The property was at the southern tip of a much larger 77-acre site Mr. Trump had owned since the early 1970s, a former freight yard that was once the largest undeveloped parcel in Manhattan. In the early 1990s, Mr. Trump had made no progress in developing the site after amassing more than $800 million in debt, most at very high interest rates, and couldn’t afford bank payments on the property.

But in 1994, two Hong Kong investors came to his rescue. They agreed to finance his vision of high-rise residences, with Mr. Trump remaining the public face of the project. He would also seek $350 million in federal subsidies.

Yet Mr. Trump was struggling to decide what to develop on the southern edge. He pursued buyers, including CBS. He boasted that the network was close to a deal for a 1.5 million-square-foot studio on the property.

But CBS eventually balked, deciding in early 1999 to stay put in its studios on West 57th Street.

A few months later, Mr. Trump was hyping the property every chance he could. “My father taught me everything I know, and he would understand what I’m about to say,” Mr. Trump said at the wake of his father, Fred Trump. Then Mr. Trump touted his plans for Trump Place. “It’s a wonderful project,” he said.

By 2000, Mr. Trump had set his sights on a new partner: Columbia, which he had heard was looking for space. A development there would have been a departure for the university. It was more than two miles from Columbia’s campus and relatively small, requiring it to be built up, with towering buildings.

Still, the idea captured the attention of several trustees and some top administrators. For more than a year, they discussed what could become of the land, mostly with officials at the Trump Organization and sometimes with Mr. Trump himself. Mr. Trump even coined a name for the potential development: “Columbia Prime.”

But in negotiations, he frequently changed his demands, even as reports would appear in Mr. Trump’s favored tabloid, The New York Post, claiming that Columbia was close to buying it.

In private, he tossed around numerous prices, topping out at $400 million, according to a Columbia official from that era, a figure that an anonymous source leaked to The Post a few times.

No matter the amount, Mr. Trump said to Columbia officials, the university would be getting such a great deal that it should also rename its business school the Donald J. Trump School of Business.

An administrator rebuffed Mr. Trump’s request. The university does rename buildings, the person told him, noting that its engineering school had been recently named for a businessman who had donated $26 million. If Mr. Trump wished to make such a gift, the person said, there were other officials at Columbia who would be eager to meet. Mr. Trump did not make a donation.

As the discussions dragged on, many people from Columbia grew frustrated with their dealings with Mr. Trump. Still, the two sides set up a meeting in a Midtown Manhattan conference room with the intention of moving a transaction forward.

A few trustees and administrators arrived with a report prepared on their behalf by a real estate team at Goldman Sachs, which attended every meeting between Columbia officials and representatives of the Trump Organization. It outlined what the investment bank considered a fair value for the land.

Mr. Trump showed up late, was informed of the university’s property analysis and became incensed.

Goldman Sachs had assigned a value in the range of $65 million to $90 million, according to a person who was in the room. In an attempt to soothe Mr. Trump, a trustee offered that the university would be willing to pay the top of the range.

It didn’t matter. A furious Mr. Trump walked out less than five minutes after the meeting had started.

The university did not formally abandon a possible expansion on Mr. Trump’s property until after Mr. Bollinger took over as president in 2002. At that time, Columbia had been considering two options: an expansion onto the Upper West Side plot or a move north into West Harlem, where Columbia had started to buy properties.

In his inaugural address, Mr. Bollinger spoke about the university’s need to expand, calling the school a “great urban university” that is the “most constrained for space.”

“This state of affairs, however, cannot last,” he added. “To fulfill our responsibilities and aspirations, Columbia must expand significantly over the next decade. Whether we expand on the property we already own on Morningside Heights, Manhattanville, or Washington Heights, or whether we pursue a design of multiple campuses in the city, or beyond, is one of the most important questions we will face in the years ahead.”

He evaluated the Trump option for a satellite campus and also began to have conversations about mending the fissure with Harlem’s community leaders, and expanding westward, creating a contiguous footprint.

He quickly determined that Harlem, not Donald Trump, was Columbia’s future. “This is an opportunity in Manhattanville to create something of immense vitality and beauty,” Mr. Bollinger told The Times in 2003. “This is not to just go in and throw up some buildings.”

Mr. Trump’s West Side property was eventually developed after the Hong Kong billionaires who owned a majority stake in it sold the entire site for $1.76 billion.

Yet Mr. Trump was outraged. He accused the investors of selling it for far less than what he could have. He sued them for $1 billion in damages. The case was dismissed, with the judge pointing out that the development had sold for $188 million more than its latest appraisal.

If he was underwhelmed by the success of the Riverside South, Mr. Trump had another asset that was appreciating: his own fame.

“The Apprentice” made its television debut in January 2004, and became an instant hit.

But Mr. Trump’s mega-stardom did not make him forget about the failed deal with Columbia.

In 2010 — about eight years after Mr. Bollinger contacted Mr. Trump to tell him the school would be expanding into Harlem — two Columbia student journalists who had written a profile of the university president received in the mail a gold-embossed letter on thick paperstock from a displeased reader, Donald J. Trump.

He included a copy of a missive he had recently sent to Columbia’s board of trustees, in which he called the Manhattanville campus “lousy” and Mr. Bollinger “a dummy.”

“Columbia Prime was a great idea thought of by a great man, which ultimately fizzled due to poor leadership at Columbia,” Mr. Trump wrote.

He signed it with a black marker and scribbled, “Bollinger is terrible!”

Mr. Trump also shared his indignation in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. “Years after the deal fell through,” the newspaper said, “Trump is still irate. ‘They could have had a beautiful campus, right behind Lincoln Center,’” Mr. Trump told the reporter and called Mr. Bollinger a “total moron.”

Mr. Trump was perhaps staying true to principles outlined in “How To Get Rich,” an advice book he co-wrote a few years after his deal with Columbia went sour.

One chapter is titled “Sometimes You Have to Hold a Grudge.”

Maggie Haberman contributed reporting.

New York

The Disaster to Come: New York’s Next Superstorm

This is what rain can do in New York City.

In July, Jessica Louise Dye was on the subway when she recorded a video of a “cascading wall of water coming at us.” Scenes like these are becoming more and more common. They also hint at what’s to come.

The next hurricane could inundate the city in a far worse way than Superstorm Sandy in 2012, according to new projections. Much of that increase has to do with extreme rain.

The largest city in the country is mostly a cluster of islands. Its inlets and rivers rise and fall with the tides.

Sandy produced a deadly storm surge, and in 2021, the remnants of Hurricane Ida introduced the damage of extreme rainfall. The next hurricane could bring both.

It would not have to be a major one. A weaker hurricane, dumping sheets of rain and moving in a northwest direction from the ocean, would wreak havoc, experts said.

First Street, a climate risk group in Manhattan, created a model of the damage a storm on such a track could have. In this example, a Category 1 hurricane would make landfall in New Jersey at high tide like Sandy, amid rainfall of four inches per hour — one of the more extreme scenarios.

The results showed a 16-foot storm surge, two feet higher than Sandy’s, which when combined with a torrential downpour, could put 25 percent of the city under water.

Today, such a storm is not impossible. It could happen about once every century, said Jeremy Porter, who leads the group’s climate implications research. “But it will become more normal with the changing climate,” Dr. Porter said.

Some of Manhattan’s most iconic spots would be submerged. Downtown, that would include parts of Chinatown, SoHo and the financial district.

In the Bronx, Yankee Stadium would be nearly surrounded by water, up to 11 feet in places.

Highways that hug Manhattan would see up to 10 feet of flooding, while farther north, a part of the Cross Bronx Expressway that dips before an underpass could be submerged up to 47 feet.

But Manhattan and the Bronx would largely fare better than the boroughs that border the ocean. Brooklyn, Staten Island and Queens, with miles of low-lying neighborhoods and dire drainage problems, would bear the brunt – over 80 percent – of the flooding.

Property damage across the city could exceed $20 billion, twice as much as Sandy caused, according to First Street.

Here are some of the neighborhoods, starting inland and moving toward the coast, that would see the worst of the destruction.

Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, could see as much as 11 feet of stormwater.

A large hilly ridge cuts through the middle of Staten Island, Brooklyn and Queens. Its natural elevation provides some of the city’s most spectacular views.

Bedford-Stuyvesant, in Central Brooklyn and north of the moraine, could see as much as 11 feet of stormwater, including along tree-lined streets with brownstones worth millions. Ground-floor apartments that can rent for as much as $4,000 would fill up like cisterns.

South of the moraine, East Flatbush could see nearly eight feet of water.

Four years ago, rains from Ida flooded the streets here.

“Water was gushing in from everywhere,” said Renée Phillips, 62, a 50-year resident. “That storm was something I’d never seen in my lifetime,” Ms. Phillips said. “And I hope and I pray that I never see it again.”

This October, Ms. Phillips’s street flooded again. Her 39-year-old neighbor drowned in his basement apartment. Ms. Phillips outside her home. Though she rents out apartments on the first floor, maintaining them is difficult because of water damage.

Based on First Street estimates, her house could face up to six feet of flooding in the next storm.

After Ida, Ms. Phillips escaped by wading through her flooded street while carrying two dogs and a cat. Her waterlogged property grew mold and the first floor had to be gutted.

She did not have flood insurance because she did not live in a designated flood zone. Ms. Phillips took out a loan for $89,000 to replace her boiler and fix the first floor. She was just beginning to consider repairs on the rest of her property when the deluge this fall set her back again. The boiler she had installed after Ida was destroyed, leaving her without heat.

“I’m distraught,” said Ms. Phillips, who was grieving her next door neighbor, and panicked about her finances.

“I feel like I have no control over the situation,” she said.

Kissena Park, a residential neighborhood in East Flushing, Queens, could get over 19 feet of storm water.

Ida flooded basement and first-floor homes here, killing three people.

Three years later, in 2024, at a community meeting, Rohit Aggarwala, the city’s climate chief and the commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection, explained the reasons to residents.

“The area is a bowl,” he said. Kissena Park also was built over waterways and wetlands, he added.

But there was a third factor, Mr. Aggarwala said: A major sewer artery was there, responsible for 20 percent of storm and wastewater in Queens. When the sewer got overwhelmed, it created a bottleneck in Kissena Park.

All of these forces were at work during Ida.

Michael Ferraro, 32, who works in information technology, was returning from moving his car to higher ground, when he discovered that his street had turned into a raging river.

“I tried to swim, but the currents were taking me down,” he said, explaining that grabbing onto a fence saved his life.

Michael Ferraro’s home was inundated during Ida. His neighborhood flooded again this fall.

Based on First Street estimates, his house could be completely submerged during the future storm they projected.

Upsizing the sewer for Kissena Park would cost billions and take decades, according to the city’s Department of Environmental Protection.

Hamilton Beach, just west of Kennedy Airport, was built over coastal wetlands. The neighborhood could see up to nine feet of flooding.

Southeast Queens was once mostly salt marsh, which provided crucial protection against flooding. But over the years, city leaders filled the marshes in to build neighborhoods, highways and Kennedy Airport.

The water frequently returns.

In Hamilton Beach, when the tide is higher than usual, water pours into the neighborhood from a nearby basin and up through the sewers.

This August, on a clear evening, it flooded again. Some residents moved their cars to higher ground. Others, walking home from work, borrowed plastic bags from neighbors to wrap around their shoes. Sump pumps wheezed, and garbage bags floated through the streets.

Roger Gendron, 63, a retired truck driver and neighborhood flood-watch leader, took it in from his second-floor porch. “A storm that is hundreds of miles off the coast is doing this,” he said. “Just imagine what a direct hit would do.”

In August, tidal flooding, a regular occurrence in Hamilton Beach, forced residents to roll up their pants and move their cars.

Roger Gendron at his house in Hamilton Beach. Water could rise to his second-floor porch in a storm, according to First Street projections.

Hamilton Beach and other areas surrounding Jamaica Bay, the largest wetland in New York City, are prone to compound flooding, when heavy rain and coastal flooding combine.

The Department of Environmental Protection, which oversees the city’s water systems, has a 50-year plan to build out such a network. It is 10 years in and has spent over $1.5 billion so far. The work includes a major sewer expansion north of Kennedy Airport.

“If the airport were still a wetland, we wouldn’t have to build a gigantic sewer under the highway,” said Mr. Aggarwala, the head of the department, on a recent tour of the work site.

In 40 years, once the entire system for southeast Queens is complete, the pipes here and in other parts of the network will be able to transport over one billion gallons of storm water to the bay.

And this is just one corner of the city. It will take at least 30 years and about $30 billion to improve the parts of the sewer system that are the most vulnerable to storm water, Mr. Aggarwala said.

Throughout New York, city leaders are reckoning with decisions that were made some 100 years ago to build infrastructure on wetlands.

“The work is endless,” said Jamie Torres-Springer, president of construction and development for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, during a recent tour of a subway yard.

The 30-acre subway yard in the eastern Bronx — the city’s third largest — was built over a salt marsh, where a tidal creek used to flow. Of the transit system’s 24 subway yards, which maintain and store thousands of train cars, 13 are vulnerable to storm surge.

The city’s two biggest yards now have flood walls, drainage improvements and other protections. Work on the eastern Bronx yard is scheduled for next year.

In Brooklyn, Coney Island would be under up to six feet of water, with bridges and roads washed out.

Sandy devastated the Brooklyn peninsula.

“We’re afraid every day that it’s going to happen again,” said Pamela Pettyjohn. During the superstorm, a sinkhole opened under her home.

She and other residents are concerned that the new developments, some of which include higher sidewalks and elevated bases that encourage water to flow under, around or through them, could worsen flooding in lower-lying areas, while taxing an already-overburdened sewer system.

And, with few ways on and off the peninsula, the addition of thousands of residents here could make a hurricane evacuation even more perilous.

Pamela Pettyjohn placed a flood barrier outside her home before a storm this summer.

Her house could face nearly six feet of flooding.

After Sandy, Ms. Pettyjohn, a retiree, spent her savings rebuilding her home. She is living without heat because salt water from the storm slowly rusted out her boiler. The soaring cost of flood insurance keeps her from buying a new one, she said.

During Sandy, many bungalows in Midland Beach flooded, and they have since been repaired and put up for sale. Some are so inexpensive that New Yorkers can own them outright. Two neighboring bungalows, for example, are on sale as a package deal for $325,000, in a city where the median price for one home is about $800,000.

Without a mortgage, though, there is no mandate to buy flood insurance. Some homeowners could lose everything in the next hurricane.

“People are still deniers here,” Mr. Tirone said. They will continue to snatch up real estate deals in flood zones, he continued, until the government dictates to them otherwise.

He added: “The question is, ‘What’s that going to take?’ ”

Methodology

The 3-D base map in this article uses Google’s Photorealistic 3D Tiles, which draw from the following sources to create the tiles: Google; Data SIO; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; U.S. Navy; National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency; General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans; Landsat / Copernicus; International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean; Vexcel Imaging US, Inc.

Times journalists consulted the following experts: Phil Klotzbach, Colorado State University; Paul Gallay, Klaus Jacob, Jacqueline Klopp and Adam Sobel, Columbia University; Franco Montalto, Drexel University; Amal Elawady, Florida International University; Ali Sarhadi, Georgia Institute of Technology; Kerry Emanuel, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Lucy Royte and Eric W. Sanderson, New York Botanical Garden; Zachary Iscol, New York City Emergency Management; Andrea Silverman, New York University; Fran Fuselli, Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition; Bernice Rosenzweig, Sarah Lawrence College; Brett Branco and Deborah Alves, Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay, Brooklyn College; Philip Orton, Stevens Institute of Technology; Jorge González-Cruz, University at Albany, SUNY; Stephen Pekar and Kara Murphy Schlichting, Queens College, CUNY; Tyler Taba, Waterfront Alliance.

New York

Driver Who Killed Mother and Daughters Sentenced to 3 to 9 Years

A driver who crashed into a woman and her two young daughters while they were crossing a street in Brooklyn in March, killing all three, was sentenced to as many as nine years in prison on Wednesday.

The driver, Miriam Yarimi, has admitted striking the woman, Natasha Saada, 34, and her daughters, Diana, 8, and Deborah, 5, after speeding through a red light. She had slammed into another vehicle on the border of the Gravesend and Midwood neighborhoods and careened into a crosswalk where the family was walking.

Ms. Yarimi, 33, accepted a judge’s offer last month to admit to three counts of second-degree manslaughter in Brooklyn Supreme Court in return for a lighter sentence. She was sentenced on Wednesday by the judge, Justice Danny Chun, to three to nine years behind bars.

The case against Ms. Yarimi, a wig maker with a robust social media presence, became a flashpoint among transportation activists. Ms. Yarimi, who drove a blue Audi A3 sedan with the license plate WIGM8KER, had a long history of driving infractions, according to New York City records, with more than $12,000 in traffic violation fines tied to her vehicle at the time of the crash.

The deaths of Ms. Saada and her daughters set off a wave of outrage in the city over unchecked reckless driving and prompted calls from transportation groups for lawmakers to pass penalties on so-called super speeders.

Ms. Yarimi “cared about only herself when she raced in the streets of Brooklyn and wiped away nearly an entire family,” Eric Gonzalez, the Brooklyn district attorney, said in a statement after the sentencing. “She should not have been driving a car that day.”

Mr. Gonzalez had recommended the maximum sentence of five to 15 years in prison.

On Wednesday, Ms. Yarimi appeared inside the Brooklyn courtroom wearing a gray shirt and leggings, with her hands handcuffed behind her back. During the brief proceedings, she addressed the court, reading from a piece of paper.

“I’ll have to deal with this for the rest of my life and I think that’s a punishment in itself,” she said, her eyes full of tears. “I think about the victims every day. There’s not a day that goes by where I don’t think about what I’ve done.”

On the afternoon of March 29, a Saturday, Ms. Yarimi was driving with a suspended license, according to prosecutors. Around 1 p.m., she turned onto Ocean Parkway, where surveillance video shows her using her cellphone and running a red light, before continuing north, they said.

At the intersection with Quentin Road, Ms. Saada was stepping into the crosswalk with her two daughters and 4-year-old son. Nearby, a Toyota Camry was waiting to turn onto the parkway.

Ms. Yarimi sped through a red light and into the intersection. She barreled into the back of the Toyota and then shot forward, plowing into the Saada family. Her car flipped over and came to a rest about 130 feet from the carnage.

Ms. Saada and her daughters were killed, while her son was taken to a hospital where he had a kidney removed and was treated for skull fractures and brain bleeding. The Toyota’s five passengers — an Uber driver, a mother and her three children — also suffered minor injuries.

Ms. Yarimi’s car had been traveling 68 miles per hour in a 25 m.p.h. zone and showed no sign that brakes had been applied, prosecutors said. Ms. Yarimi sustained minor injures from the crash and was later taken to a hospital for psychiatric evaluation.

The episode caused immediate fury, drawing reactions from Police Commissioner Jessica Tisch and Mayor Eric Adams, who attended the Saadas’s funeral.

According to NYCServ, the city’s database for unpaid tickets, Ms. Yarimi’s Audi had $1,345 in unpaid fines at the time of the crash. On another website that tracks traffic violations using city data, the car received 107 parking and camera violations between June 2023 and the end of March 2025. Those violations, which included running red lights and speeding through school zones, amounted to more than $12,000 in fines.

In the months that followed, transportation safety groups and activists decried Ms. Yarimi’s traffic record and urged lawmakers in Albany to pass legislation to address the city’s chronic speeders.

Mr. Gonzalez on Wednesday said that Ms. Yarimi’s sentence showed “that reckless driving will be vigorously prosecuted.”

But outside the courthouse, the Saada family’s civil lawyer, Herschel Kulefsky, complained that the family had not been allowed to speak in court. “ They are quite disappointed, or outraged would probably be a better word,” he said, calling the sentence “the bare minimum.”

“I think this doesn’t send any message at all, other than a lenient message,” Mr. Kulefsky added.

New York

Video: What Bodegas Mean for New York

new video loaded: What Bodegas Mean for New York

By Anna Kodé, Gabriel Blanco, Karen Hanley and Laura Salaberry

November 17, 2025

-

Business1 week ago

Fire survivors can use this new portal to rebuild faster and save money

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoFrance and Germany support simplification push for digital rules

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoCourt documents shed light on Indiana shooting that sparked stand-your-ground debate

-

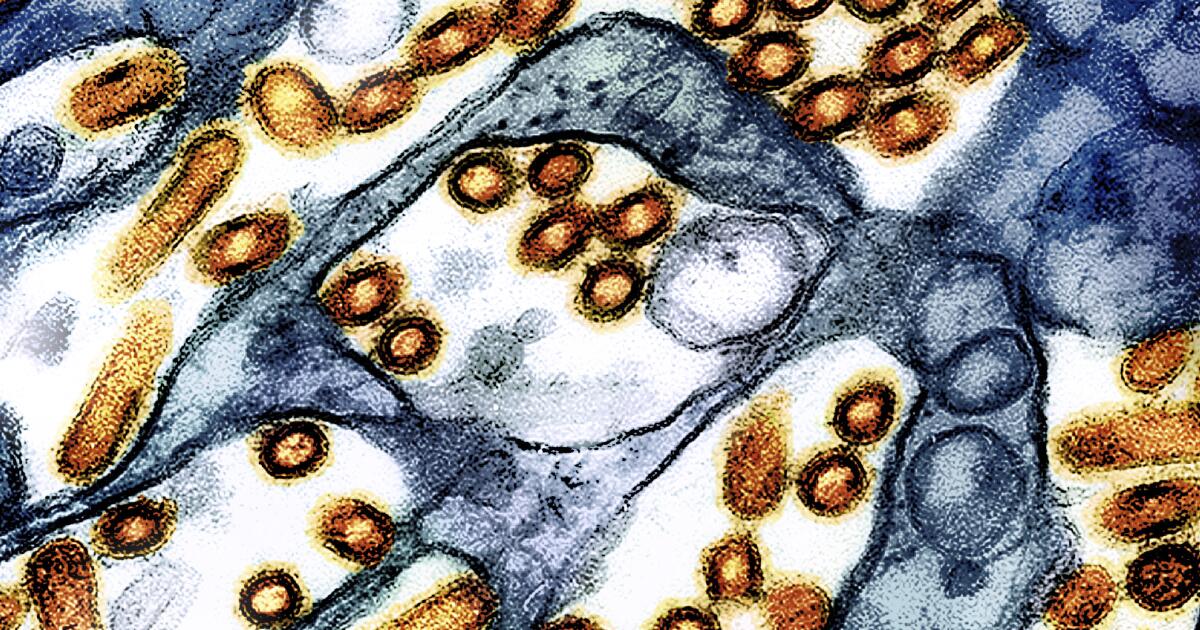

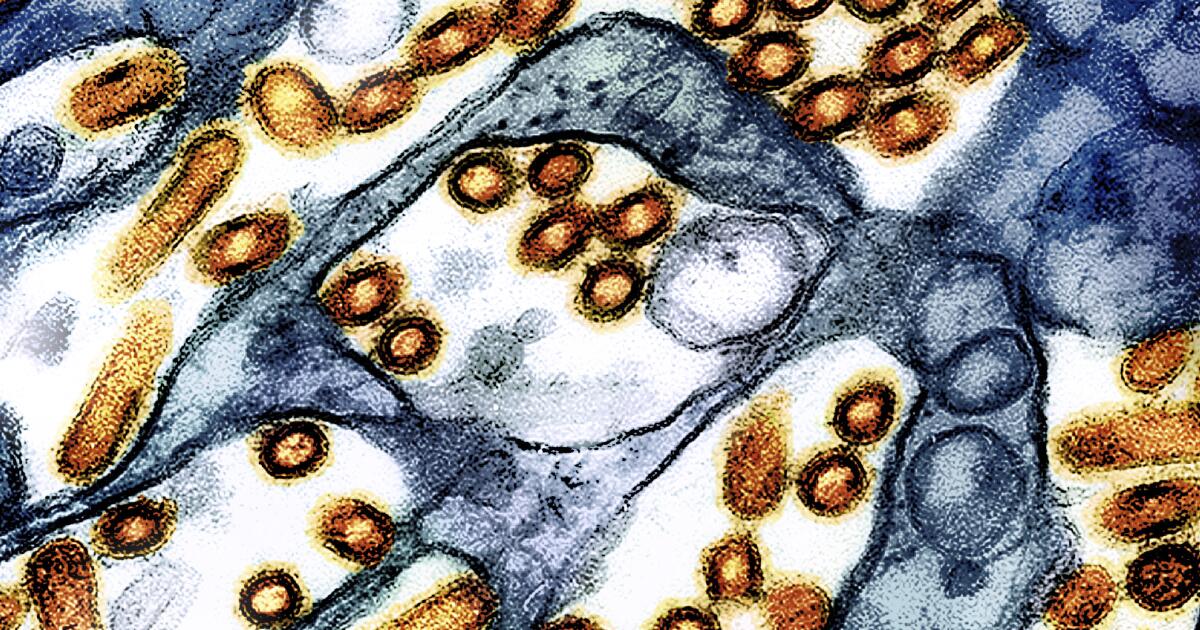

Science4 days ago

Science4 days agoWashington state resident dies of new H5N5 form of bird flu

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSinclair Snaps Up 8% Stake in Scripps in Advance of Potential Merger

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCalls for answers grow over Canada’s interrogation of Israel critic

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDuckworth fires staffer who claimed to be attorney for detained illegal immigrant with criminal history

-

Business1 week ago

Amazon’s Zoox offers free robotaxi rides in San Francisco