News

Who Can Achieve the American Dream? Race Matters Less Than It Used To.

Lawrence Cain Jr., a Black millennial in Cincinnati, did not have a comfortable upbringing. His family didn’t have much money. They took few vacations. But Mr. Cain did have a strong community — which he said taught him entrepreneurship and showed him he could dream big. His mom took double shifts at nursing homes. She and her father ran their own businesses. Mr. Cain worked at his grandfather’s deli starting at 11 years old.

Mr. Cain, 35, got a two-year degree in business management and first worked as a bank teller and financial adviser. In 2015, he was ready to forge his own path. He started a financial coaching business, Abundance University. Business is booming. Today, Mr. Cain identifies as solidly middle-class. He and his wife, a teacher, can support themselves, their three children and then some. They take holidays around the country. “My kids are spoiled,” he joked.

Mr. Cain in many ways reflects the trends captured by a new Harvard study. It looked at two groups: a Gen X cohort born in 1978 and a millennial cohort born in 1992. The researchers combed through decades of anonymized census and tax records to which the federal government gave them access. The data covered 57 million children, which offered the researchers a more detailed view into recent generations than previous economic studies had. Adjusting for inflation, they then measured these groups’ ability to rise to the middle and upper classes — their economic mobility.

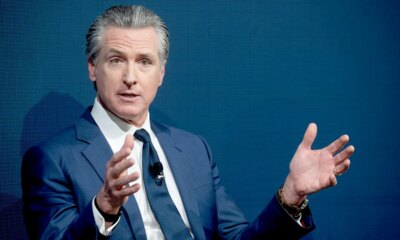

Lawrence Cain Jr. of Cincinnati did not have an easy upbringing, but today identifies as middle-class.

Asa Featherstone, IV for The New York Times

The researchers found that Black millennials born to low-income parents had an easier time rising than the previous Black generation did. At the same time, white millennials born to poor parents had a harder time than their white Gen X counterparts. Black people still, on average, make less money than white people, and the overall income gap remains large. But it has narrowed for Black and white Americans born poor — by about 30 percent.

The community you come from has a huge effect on your economic mobility. For centuries, this meant a tremendous advantage for white Americans, even those born into low-income families. But in a surprising shift, the study suggests that advantage is not as large as it once was.

On the flip side of Mr. Cain is someone like Derek Brown, a white millennial in Cincinnati. His parents were separated, and he was raised in two worlds, one middle class and one poor. His dad worked at a General Electric factory, a steady job that provided a more middle-class life. His mom worked long hours at gas stations, Mr. Brown said, but she struggled. Sometimes, she couldn’t pay the bills, and their power was cut off at home. “It was never the dream,” he said.

Unlike Mr. Cain, Mr. Brown did not have a strong sense of community, as he bounced between his mother, his father and his grandparents. Watching his mother, he came to believe that hard work does not necessarily lead to a better life. He once hoped to become a journalist when he grew up, but he gave up that dream to pursue what he believed would be a more realistic way to pay the bills.

The Northside neighborhood in Cincinnati has crime rates that are higher than the national average.

Asa Featherstone, IV for The New York Times

About five miles south of Northside, the Over-the-Rhine district is known for its dining and culture.

Asa Featherstone, IV for The New York Times

Today, Mr. Brown, 34, feels that he is behind where his father was. He works as a hairstylist at Great Clips. He lives paycheck to paycheck. He currently has a $3,000 medical bill that his insurance didn’t cover, and he doesn’t know how he’ll pay for it. He’s always scared of the next big cost. “I have really bad financial anxiety,” he said. “I don’t even want to drive to places. What if my car breaks down?”

“It’s instilled in your head: Anything is possible if you work hard for it,” Mr. Brown added. “What no one tells you is that for some people there is a glass ceiling, and you just don’t see it until you hit it.”

As the Harvard study shows, the difference in outcomes between Mr. Cain and Mr. Brown is increasingly typical. But the racial differences weren’t the only findings. Over the decade and a half of the study, the opportunity gap between white people born rich and those born poor expanded by roughly 30 percent. One possible interpretation: “Class is becoming more important in America,” while race is becoming less so, Raj Chetty, the study’s lead author, told me.

Let’s look at how class has dictated outcomes. For white Americans in particular, changes in mobility significantly differed between those born poor and those born rich.

Imagine four white children: a rich one and a poor one born in 1978, and the same pair born in 1992.

At 27 years old, the poor white millennial would make less money on average than the poor white Gen X-er. The white Gen X child born rich, unsurprisingly, could expect to make much more.

And while poor white millennials do worse than their predecessors, rich white millennials do better.

The change has widened class divides in the United States.

The data didn’t just show that people’s lives were guided by immutable facts like class and race. It suggested that a person’s community — the availability of work, schooling, social networks and so on — plays a central role.

Imagine a thriving American community. What makes it successful? Jobs are an important factor. So are effective schools, nice parks, low crime rates and a general sense that success is achievable. In a thriving place, people not only get good jobs, but they also know that those jobs can lead to better lives, because they see and feel it all the time. “Our fates are intertwined,” said Stefanie A. DeLuca, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins University who was not part of the Harvard study. “The fortunes of those around you in your community also impact what happens to you.”

On an individual level, Lawrence Cain Jr. benefited from both his mother’s jobs and his family’s support and entrepreneurship. They helped plant the idea that he could work hard and become a business owner. “If your networks are doing well, you may think that you can do well, too,” said David B. Grusky, a sociologist at Stanford who was also not part of the Harvard study.

The inverse is also true. Derek Brown said that his childhood was too chaotic for him to develop strong social roots. Across a community, bad events can cascade and cause things to fall apart. Consider a neighborhood in which crime rises. Businesses move to safer locations. The tax base shrinks, and infrastructure deteriorates along with schools. People flee, and social networks splinter. A sense of despair takes over among the people who remain.

Real-world effects

A cookout in the Northside neighborhood.

Asa Featherstone, IV for The New York Times

Why did things get worse for poor white people and their communities, but not for their Black counterparts? One explanation focuses on the availability of jobs. The researchers found that community employment levels are an important predictor of differences in economic mobility.

In the real world, the situation might have played out like this: Over the past few decades, globalization and changes in technology have caused many jobs to go from the United States to China, India and elsewhere. These shifts appear to have pushed white people out of the work force, while Black people found other jobs.

There are several explanations for the racial disparity. White workers might have had more wealth or savings to weather unemployment than their Black counterparts did, but at a cost to their upward mobility. They might also have been less willing to find another job. A steel mill that shut down could have employed not just one worker but his father and grandfather, making it a family occupation. People in that situation might feel that they lost something more than a job — and might not settle for any other work.

The places where Black workers live were generally less affected by job flight than the places where white workers live. And compared with earlier generations, Black workers today are less likely to face racial prejudice in the labor force, making it easier for them to find work. While a white worker might have a generational connection to a steel mill job, a Black worker often does not, because segregation kept his parents and grandparents out.

These trends add up to decades of lost economic progress for low-income white people and the opposite for Black Americans.

Share of children born low-income who are no longer low-income at age 27

Source: Opportunity InsightsChange in persistence of poverty

The findings do not show that Black opportunity took away from white opportunity. In fact, the study found that white mobility had deteriorated least in the places where Black mobility had improved most.

In some ways, the research might prove politically controversial. Conservatives have long argued that white working-class Americans fell behind, while liberals have emphasized helping minority groups through policies like affirmative action. The left points out that Black and brown people remain far behind their white counterparts and therefore need more help from social programs. The right believes that’s outdated thinking, if it was ever correct. The study provides fodder for both sides.

“The left and the right have very different views on race and class,” said Ralph Richard Banks, a law professor at Stanford who wasn’t involved in the research. “The value of the study is that it brings some unimpeachable evidence to bear on these questions.” He added, “There’s something in it for everyone.”

For their part, the Harvard researchers feel optimistic about one major finding: Economic mobility can change relatively quickly. It improved in Charlotte, N.C., since 2014, after an earlier study by the Harvard group drove the city to make new investments. Local leaders got nonprofits and businesses, including Bank of America, which is based there, to provide job training, education, housing and other services to poorer residents. The researchers hope the results persuade other policymakers around the country to make similar investments.

“It actually is possible for opportunity to change in a serious way, even in a relatively short time frame,” said Benjamin Goldman, one of the Harvard researchers.

These trends don’t apply evenly to every part of the country. Some places had bigger or smaller gains for Black Americans and bigger or smaller losses for white Americans, as this map shows:

Source: Opportunity Insights

Note: Maps show expected incomes at age 27 in counties with at least 250 children in each relevant group. Counties shown in gray do not have estimates due to insufficient data.Expected income at age 27 for children born poor, by county

Mr. Cain believes his story shows that hard work can make a better life possible. He saw just how much his mother, as a Black woman, needed to do to get by. He faced his own doubts and troubles, including racism and discrimination, growing up. But he always remembered what his mother and grandfather taught him — that he could achieve his version of the American dream.

“I can chase that feeling every day of doing things for me, doing things with people I love and making an impact on the community,” Mr. Cain said. “That’s success for me.”

How common are stories like Mr. Cain’s where you live? You can see how economic mobility has changed in your county through this interactive:

Expected income at age 27

Black

White

Comparing incomes for Black and white children born poor, by county

News

Mass shooting at Austin, Texas bar leaves at least 3 dead, 14 wounded, authorities say

Gunfire rang out at a bar in Austin, Texas, early Sunday and at least three people were killed, the city’s police chief said.

Austin Police Chief Lisa Davis told reporters the shooter was killed by officers at the scene.

Fourteen others were hospitalized and three were in critical condition, Austin-Travis County EMS Chief Robert Luckritz said.

“We received a call at 1:39 a.m. and within 57 seconds, the first paramedics and officers were on scene actively treating the patients,” Luckritz said.

There was no initial word on the shooter’s identity or motive.

Davis noted how fortunate it was that there was a heavy police presence in Austin’s entertainment district at the time, enabling officers to respond quickly as bars were closing.

“Officers immediately transitioned … and were faced with the individual with a gun,” Davis said. “Three of our officers returned fire, killing the suspect.”

She called the shooting a “tragic, tragic” incident.

Austin Mayor Kirk Watson said his heart goes out to the victims, and he praised the swift response of first responders.

“They definitely saved lives,” he said.

Davis said federal law enforcement is aiding the investigation.

News

A long-buried recording and the Supreme Court of old (CT+) : Consider This from NPR

News

2 Survivors Describe the Terror and Tragedy of the Tahoe Avalanche

The blizzard blew so fierce that the skier at the head of the line kept disappearing into a whiteout. The winds were gusting over 50 miles per hour. Almost four feet of fresh powder had piled up and more was falling every minute.

At the back of the line was Anton Auzans, trudging behind 12 other backcountry skiers climbing through a clearing high in California’s Sierra Nevada. He had his hood pulled low against the pelting wind.

Then came a single word yelled by a ski guide somewhere ahead: “Avalanche!”

Mr. Auzans looked up in time to see a wall of white dotted with strange blurs of color. In the moment before it reached him, he realized that the colors were the tumbling skis and clothing of the other skiers.

He dove behind a dead tree for protection, but the snow was surging down the mountain like a raging river. It poured around the trunk, dragged him away and swallowed him in darkness.

Hundreds of thousands of pounds of snow rushed into the clearing, slowing as it spilled over flatter ground, and settled into a dense pile and a terrible silence. The slide had buried everyone in the group. Almost.

Two men from the group had fallen behind.

Back in the woods, Jim Hamilton was struggling with a sticky ski binding that had refused to lock onto his boot and caused him to fall behind. He was cursing his bad luck.

He was hustling to catch the group, following their ski track through the woods. With him was a ski guide. Mr. Hamilton expected to catch sight of the others at the next clearing. Instead, their track abruptly ended at a rough berm of snow debris, as if a giant plow had driven through.

Mr. Hamilton had been too far behind to hear the warning or the rush of snow. For a second he was mystified. Where was everybody?

Then he heard Mr. Auzans yell. “Major avalanche! Major avalanche! We have people buried!” Mr. Auzans’s head had just poked out of the snow.

Anton Auzans and Jim Hamilton are two survivors of the deadliest avalanche in modern California history. This account is based on a number of interviews with the two men conducted over several hours, in which they offered the first eyewitness telling of what happened.

The Feb. 17 avalanche killed nine skiers who were among 15 people on a guided trip high in the mountains near Lake Tahoe, including six women who were all close friends.

The two men, both lifelong skiers who had never met before the trip, said that as the storm beat down, conditions steadily grew worse, but their guides largely stuck to an itinerary laid out long before the storm, and led the group beneath steep terrain where a massive slide buried nearly everyone. The few skiers who were free dug desperately to save the others, but were overwhelmed by the number of people trapped, and by the unrelenting blizzard that threatened to cause another deadly slide.

In the days since, many in the public, including some veteran backcountry skiers, have raised questions about why four experienced guides left a protected backcountry hut during a historic storm and led their group across avalanche terrain, while not spreading skiers out so that one avalanche would not take out the whole group.

Those questions remain largely unanswered. The Nevada County Sheriff’s Office and California’s workplace safety agency, Cal-OSHA, are investigating whether there were safety violations or criminal negligence by the company that led the trip, Blackbird Mountain Guides. No findings have been announced.

There were four other survivors: One ski guide, two women in the group and a third man who had signed up for the trip. The surviving women declined to comment through a spokeswoman, as did the other ski client. The guide, a man, could not be reached for comment.

In a statement after the accident, Blackbird Mountain Guides, asked people not to speculate, adding, “It’s too soon to draw conclusions, but investigations are underway.”

A Welcome Forecast of Heavy Snow

The trip started on a blue-sky day.

Mr. Auzans and Mr. Hamilton arrived at Donner Pass, where Interstate 80 cuts through a gap in the mountains, on the morning of Sunday, Feb. 15. The weather was mild and snowy peaks were shining under a clear sky.

Sunday: Groups skied to huts

The plan was to ski three miles over a high mountain ridge east of the highest summit in the area, Castle Peak, to a hidden subalpine basin called Frog Lake. There, at 7,600 feet, sat a cozy collection of backcountry huts that would provide the skiers with hot meals, warm beds and a launching point for human-powered climbs up remote mountains to ski untracked slopes.

A monster winter storm was set to move in that night and drop up to eight feet of snow over four days. The local avalanche forecasting office warned of possible “widespread avalanche activity” and slides large enough to bury people in the days ahead. But the skiers viewed the weather not as a concern, but as a stroke of good luck.

For six weeks the region had gone without a significant storm, leaving the snow thin and crusty and not much fun to ski. The storm promised to bring what the skiers had hoped for, what they had each paid almost $1,500 for: bottomless fresh powder.

At the pass, the two clients were greeted by their guides from Blackbird Mountain Guides, — Andrew Alissandratos, 34, and the guide who survived — and by the third man.

A second group had also hired Blackbird to head to the huts that day: Eight friends, all women in their 40s or early 50s, who had been taking backcountry trips together for years. Many of them also liked to surf. Most had high-powered jobs and impressive résumés. Both groups were led by Blackbird, and had signed up for the same hut trip, but each group had their own pair of guides.

The four guides from Blackbird all had extensive experience and formal training. They checked that everyone had the required safety gear — an avalanche beacon for locating people who are buried; a long, folding probe to pinpoint them under the snow; and a shovel for digging them out. Mr. Auzans and Mr. Hamilton had both taken basic avalanche safety classes, but neither had experienced an avalanche before.

When the topic of the impending storm came up, Mr. Hamilton said the guides told him not to worry, they knew how to pick safe terrain. They would have to stay on treed slopes and avoid the steep inclines that many skiers love, but he said one guide told him there would be so much powder that no one would care.

The groups put climbing skins on the bottom of their skis to grip the snow and climbed up to a ridge on the side of Castle Peak, about 1,700 feet above the freeway.

Mr. Hamilton snapped pictures of views that spilled out seemingly forever. He was 65, a software engineer and grandfather, and had moved to California from Massachusetts a year before. He had only been backcountry skiing four times and would never have attempted a trip like this without expert guides. But he wanted to experience the renowned deep Lake Tahoe backcountry powder, so he had looked online and found the Frog Lake trip on Blackbird’s website. There was one slot left.

“Wow,” he had said to himself, “it’s meant to be.”

On the ridge, the skiers took off their climbing skins for a long ski down an open bowl to a steep snow gully called Frog Lake Notch that cut beneath a granite summit called Perry’s Peak.

On a big powder day, Frog Lake Notch would be a natural avalanche path, but that Sunday, the old snow was firm and safe. By early afternoon, they had reached the huts at Frog Lake.

It was just the kind of experience Mr. Auzans was hoping for.

A 37-year-old electrician in the Bay Area with a young son, he had grown up snowboarding at nearby resorts and in recent years had grown increasingly interested in the backcountry.

He loved the serenity and beauty of the mountains. In summer he backpacked and camped. In winter, backcountry skiing offered the same solitude and grandeur, with the added bonus of primo powder.

At the same time, he knew there was added danger. On the handful of backcountry day trips he had taken, he always went with guides because he did not completely trust himself.

A Rising Danger

Frog Lake’s main hut had a fully stocked kitchen and big leather chairs set in front of a crackling fire. After a dinner of ravioli, the men settled in by the hearth.

Mr. Auzans cracked open the book he had brought on the history of the Donner Party. He was, by his own admission, obsessed with stories of disaster and survival, and wanted to learn about the group of pioneers, who in 1846, tried to cross the Sierra Nevada and got trapped by heavy snowfall. Nearly half of them died and some, stranded for months by deep snow, resorted to cannibalism. Donner Pass still bears their name.

The book sparked a discussion around the fire about the disaster, then other historic disasters.

As they talked, one of the men observed that most disasters aren’t caused by just one thing, but by a series of small events that led to a catastrophe.

On Sunday night it started to snow hard. By the next morning, the huts were covered by nearly a foot of fresh powder and it was still dumping.

The three male clients and the group of women gathered in the main hut for breakfast. While they ate, the four guides met in a separate room to make a plan for the day.

Early Monday, the Sierra Avalanche Center, which forecasts backcountry snow conditions in the region, posted an update: “Avalanche danger is rising. Backcountry travelers could easily trigger large avalanches today.” The center added: “Consider avoiding avalanche terrain in areas where clues to unstable snow are present.”

The forecast now said that the hazard, on a scale of 1 to 5, had increased to Level 3, with “considerable” danger, up from Level 2, with “moderate” danger, on Sunday. But the center continued to warn that, by Monday night, the hazard could increase to Level 4, with “high” danger.

Whether the guides checked those forecasts or conferred with Blackbird headquarters is unclear, the two men said in interviews, because the guide meeting happened behind closed doors. Mr. Hamilton said that the huts did have an internet connection. Blackbird Mountain Guides said in a statement, “Guides in the field are in communication with senior guides at our base, to discuss conditions and routing based upon conditions.”

Most avalanches occur on slopes between 30 and 45 degrees. The guides told the group that they would climb about 800 feet through the trees on the east side of another nearby summit, called Frog Lake Peak, and ski a 25-degree slope that would be safe.

The guides did not ask for feedback or if anyone had misgivings, Mr. Hamilton and Mr. Auzans said, and no one spoke up.

Avalanche prediction has improved dramatically since the 1980s, but knowing when snow is likely to slide has not led to a drop in fatalities. Many backcountry users continue to go into dangerous terrain, even when advised of the risk.

That has caused avalanche safety experts in recent decades to recognize that accidents have as much to do with failures in human decisions as they do with failures in snow layers. In response they have shifted education toward helping people spot human factors that push them to take dangerous risks.

Backcountry users are taught to recognize a group of human decision-making traps that can make getting caught in an avalanche more likely, said Sara Boilen, a psychologist in Montana, an avid backcountry skier and a snow safety researcher who regularly gives an avalanche safety talk.

People skiing familiar terrain — such as experienced guides on home turf — are more likely to assume a familiar route is safe. Skiers who see an opportunity as scarce or fleeting — such as a long-awaited trip or fresh powder — are more likely to downplay the danger. Individuals wanting to fit in with the group may be reluctant to speak out. Novices are prone to defer to someone they see as an expert, and not question their decisions.

In groups of six to 10, statistics show, the risk grows substantially, as numbers give the illusion of safety and unspoken competition pushes the tolerance for risk.

Over time, Dr. Boilen said, taking risks can become normalized.

“It’s very hard to avoid. I’ve seen it in my friends, I’ve seen it in myself,” she said. “You can creep past a red line you would never intentionally step across.”

The ski from the Frog Lake huts on Monday turned out to be fantastic. The guides chose enjoyable runs. The snow was deep and soft. There were no signs of avalanches. Both groups returned to the huts wet, tired and happy, Mr. Hamilton said.

“It was everything you thought it would be. Just epic. And I never once felt like we were in danger,” he said. “I remember watching the women fly by me and they are having a blast.”

Fleeing Into a Storm

By Monday night the snow was hitting harder than ever.

At midnight, the wind started blowing steadily from the southwest, gusting over 40 m.p.h. It howled through the trees and shook the huts.

Monday: Strong winds caused snow to drift

The wind drove snow across the bare peaks above Frog Lake, depositing tons of loose powder on northern slopes in deep, unstable piles. On Perry’s Peak, just above the huts, a pile started to accumulate on a bare slope with an angle of about 35 degrees. It was prime avalanche terrain. It was also right above the path the skiers would take to try to get back to their cars on Donner Pass.

When the skiers woke on Tuesday, the chance of avalanches had increased from possible to likely, according to the Sierra Avalanche Center forecast.

The guides once again held a morning planning meeting in a separate room while their clients had breakfast. When they came out, they told the skiers the groups had to cancel a planned ski lap and leave before conditions got worse.

“‘We have to get out of here now,’” Mr. Auzans recalled them firmly telling the groups.

Returning the way they came in, through Frog Lake Notch, was a no go. The steep slopes were now too dangerous. That left several alternatives, some seemingly riskier than others.

The website for the Frog Lake Huts offered an alternative path down a tree-covered slope to the southeast. There was also a one-lane road to the huts, closed in winter, that went east through safe terrain. Both routes were longer, and would have left the skiers far from their cars.

Tuesday: Skiers returned to trail

A third possibility was to stay in the huts, which had food and water and plenty of room. But the guides never mentioned the option, the men said. Instead, a fourth alternative was chosen by the guides. The groups would head for the cars, retracing much of their path in, but would avoid Frog Lake Notch by going around the back of Perry’s Peak.

Why the guides chose that course of action was not clear to the two men. There was no discussion with clients, Mr. Hamilton and Mr. Auzans said, and no clients openly raised concerns.

“I didn’t say anything,” Mr. Auzans recalled. “I’m not an expert and so I decided to trust the plan.”

An Attempt to Get Out

Winds were gusting at over 50 m.p.h. when they left. At times the skiers could not see more than a few feet.

The women’s and men’s groups combined into one party with four guides, and started zigzagging up a gentle slope to the ridge of Perry’s Peak, 500 feet above the huts.

The snow was hip deep without skis on. The guides took turns in the lead, packing a trail for the others to follow, but it was slow going. An hour later, they had covered less than a mile.

As they trudged uphill, skiers naturally bunched up behind the leader. At points on the climb the guides stopped the group and sent skiers one at a time across steeper slopes.

At around 10 a.m. they reached the ridge, stopped in the howling wind to pull off their climbing skins, and skied down the north side.

Mr. Hamilton watched the women, all veteran powder skiers, slip along effortlessly. He was not as graceful. He fell and struggled to get up. By the time they regrouped at the bottom, it was about 10:45 a.m.

The group now faced a mile-long climb up a gentle valley beneath Perry’s Peak. Beyond it was a long downhill glide to the cars. No part of the path crossed steep slopes. The group appeared to be home free.

The women put on their climbing skins ahead of the men and left with the lead guide to break trail. Mr. Auzans and the third client soon followed.

Mr. Hamilton tried to hurry, but could not get his boot into his binding. The guide at the rear of the group waited with him. Finally, they heard it click into place and moved up the trail.

Tuesday: Minutes before avalanche

A Scream, and Then Silence

At about that moment, the wind-piled mass of snow on the north side of Perry’s Peak failed. Untold tons rushed down like a tsunami, picking up speed as it tumbled the equivalent of 40 stories.

What triggered the avalanche may never be determined. The careful investigation that might provide answers, experts say, would be difficult because the storm and efforts by rescuers to stop further avalanches likely covered signs in the snow that could have provided clues. But the impact was immediately clear.

Directly in the path of the avalanche, the other 13 skiers were climbing a gentle slope through a clearing. Nearly all of them were bunched up behind the lead guides who were breaking trail. Mr. Auzans was last in line.

The skiers were not spread out to cross avalanche terrain. The clearing did not pose an obvious danger. The slope was only about 20 degrees — not steep enough for snow to slide. It remains unknown if, in the blowing snow, the guides realized that a steep slope towered just above them to the left.

“Avalanche!” was all Mr. Auzans heard.

By the time he looked up, the rest of the group had already been swallowed. The snow pushed him over and dragged him down. As he was being buried, the survival stories he loved to read flashed in his mind and he put his hands over his face to try to make an air pocket.

Everything went black. He was packed too tightly to move. He knew from his training that he had to get out soon or he would likely die.

If people buried in an avalanche are rescued within 20 minutes, accident data shows, 90 percent live. But in the next 15 minutes, carbon dioxide from their own breathing builds up in the snow, the heat of their breath can form an ice shield that blocks all air, and the survival rate drops to 30 percent. It then drops steadily as time goes on.

Trapped in the snow, Mr. Auzan thought about his 3-year-old son and never seeing him again. He said a rage built up inside him and gave him the strength to push his hands free. Suddenly, he was looking at daylight.

He struggled to make the hole bigger, broke through and sat up. He was expecting to see a commotion of rescue activity. There was only silence.

“This is bad,” he thought.

Moments later, Mr. Hamilton and the guide that was at the rear came through the trees.

“We have people buried!” Mr. Auzans shouted. He pointed to the last spot he had seen anyone.

The guide pulled his avalanche beacon from his jacket, unfolded his probe and hurried toward the signal.

Mr. Auzans was stuck — his boots were still attached to his skis, which were buried in the snow. He dug to work himself free.

Mr. Hamilton spotted a ski pole sticking up from the debris. It started to wave. He skied over and saw an arm of the third male client. He had made an airway with one arm, and was able to talk through the hole.

Don’t worry about me, I’m OK, Mr. Hamilton remembers him saying. Go look for other people.

Minutes were ticking by. Mr. Auzans dug himself out, grabbed his shovel and went to help the guide whose probe had found a skier about four feet under the snow.

The digging was hard. The slide had compacted the snow into something less like powder and more like cement. It took a number of minutes to get down to the skier.

They uncovered the face of a woman. As they brushed away the snow they kept asking if she was OK. She only moaned, but that meant she was breathing. The guide and Mr. Auzans immediately moved to try to find more skiers, leaving all but the area around the woman’s face still buried.

A few feet away the probe found a second skier. They dug steadily, hacking at the hard snow. As they dug, Mr. Hamilton went back to the other male client and began to dig him out, hoping he could help with the rescue.

About four feet down, the guide and Mr. Auzans found a second woman. Brushing the snow from her face, they saw her eyes blink. She moaned. Breathing. They told her they needed to go look for more survivors.

Somewhere in the blur of digging, Mr. Auzans called 911. It was 11:30 a.m. He reported a slide with multiple people buried. Rescuers immediately went into action.

At least 30 minutes had passed since the slide, Mr. Auzans estimated. Time was running out.

While shoveling to the second woman, they had encountered someone’s leg and another person’s backpack. The group seemed to all be buried close together.

Within minutes they had uncovered the head of a third skier. It was one of the male guides. But when they tried to revive him, they got no response.

Without stopping, they dug down to a fourth skier. A woman. She, too, appeared lifeless.

‘We Had to Save the People We Knew Were Alive’

Now the men above the snow faced a bleak decision.

It was about noon. About an hour had passed since the slide. There were seven people still unaccounted for, but the chances of finding them alive seemed slim.

The storm was still hitting with savage force. Another avalanche could hit at any moment. The two women who were alive were still mostly buried. They seemed to drift in and out of consciousness as snow blew in on their faces.

The men knew if they did not rescue the women and move to safety that they all might die. They made the decision to stop the search.

“We were all in danger. We did as much as we could. We pushed until we started finding people that were deceased. Making the decision to stop the search was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do,” Mr. Auzans said afterward. “What are our priorities? We had to save the people we knew were alive.”

The group turned their efforts to freeing the women. When they pulled the first one up to the surface, she slumped over and mumbled that she just needed to sleep. Mr. Auzans got her standing, but found that she could barely walk.

The guide pulled the second woman out, and she started to cough up blood.

They knew they had to move out of the avalanche path. They led the women into the woods, leaving the clearing and the people buried there.

The decision has weighed on both men in the days since.

“I honestly tried my best. I tried my best,” Mr. Auzans said in an interview from his home on Monday, less than a week after the avalanche. “I was buried. I helped to save three people.”

He said he wished they could have saved them all, adding, “My heart goes out to all the families of the deceased.”

Tuesday: Waiting for rescue

At about 12:30 p.m., Mr. Auzans texted 911 that they were moving to safety. The guide dug a snow pit, then laid a tarp over the top to make a crude shelter and put the women inside in sleeping bags. They began a long wait.

Rescuers knew where the group was, but with the storm, a helicopter was not an option. Snowmobiles and snowcats could not reach them. The group thought there was a good chance they would have to spend the night.

They put their water in their jackets to keep it from freezing. They built a larger snow pit where everyone could stay warm.

For hours they waited in the storm. Some kept their emotions at bay by keeping busy, others broke down, overwhelmed by the enormous loss and the thought of the devastation ahead for the many loved ones of the dead.

At about 5:30 p.m., just as it was getting dark, about a dozen rescuers arrived on skis.

With avalanche conditions still high and daylight fading, the rescuers decided the priority was to get the survivors out.

The only way was on skis. The women had regained enough strength to move on their own. The rescuers found skis for them in the pile of debris.

In the dark, using headlamps, the rescuers led the five survivors back over to the ridge on Perry’s Peak, and down to the huts, where snowcats and an army of other rescuers were waiting.

Left behind on the dark mountain were the six friends who traveled together: Carrie Atkin, Liz Clabaugh, Danielle Keatley, Kate Morse, Caroline Sekar and Kate Vitt. And the three veteran guides: Andrew Alissandratos, Nicole Choo and Michael Henry.

It would be days before the storm relented and rescuers could return to retrieve them.

Methodology

The positions of the skiers and the extent of the avalanche path are approximate based on survivor accounts, an avalanche report from the Sierra Avalanche Center and avalanche experts. New York Times journalists built the 3-D model of the area using a 2021-2022 laser scan from the United States Geological Survey.

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Denver, CO4 days ago

Denver, CO4 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT