My mother’s romance with her second husband hardly looked promising at first due to their language barrier. He was from Wisconsin and spoke only English. She was from Colombia and spoke only Spanish.

Yet in 1986, shortly before I turned 11, they married. Overnight, Glenn Hovde, a carefree bachelor who enjoyed playing golf, became a father to five girls, ages 4 to 19. Only my two oldest sisters spoke English, because they had each spent a year in the United States with our aunt. It was while visiting her sister that my mother first met my future father.

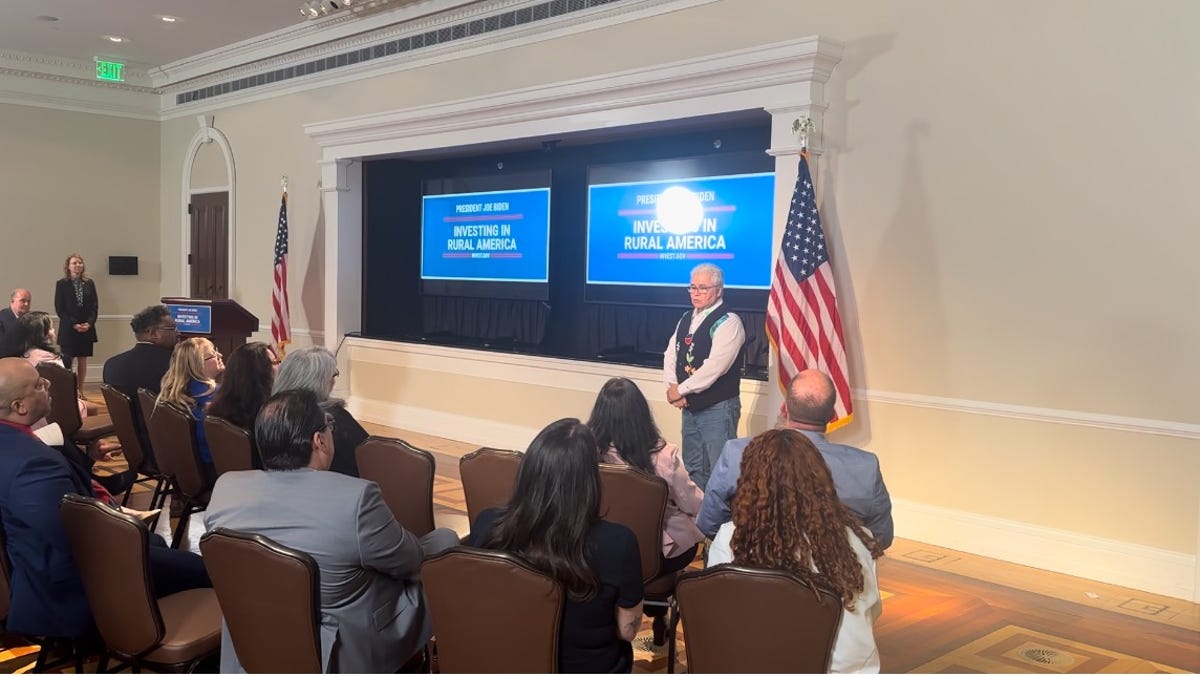

Adriana Mateus

Early on, Mom and Glenn resorted to sign language and a dictionary to communicate. My sisters and I helped each other connect with our new father, translating and using nonverbal cues as we adjusted to a new home and culture in Madison. But Glenn’s warmhearted personality, in providing the support and protection we craved, quickly won us over.

People are also reading…

So did our newfound liberation. Colombia in the 1980s was challenging and, at times, violent. Glenn, dressed casually and padding around in Birkenstocks, encouraged us to ride bikes, swim in the lake near our home and play tennis in the park.

During that first year, Glenn did most of the cooking. New aromas and scents became familiar, including the lightly spiced sloppy joes that made frequent appearances at our dining room table. Another item had an unusual flavor. “It’s just potatoes,” I suspect Glenn told us when we inquired. Colombia has a variety of potatoes, including ones used in many traditional dishes. While I was not a potato connoisseur, I was disappointed to learn they came from a Betty Crocker box.

Glenn Hovde, center, is surrounded by his large family in 2006. They include, back row from left: Lucia Mateus, Andrew Hovde and Elizabeth Guzman. In the middle row, from left, are Adrian Mateus, Myriam Hovde, Hovde and Constanza Mateus. Cristina Daza is in front.

By the time our maternal grandmother, whom we called Lita (from Abuelita), joined us after her immigration papers were complete, we had a good grasp of English, though we still spoke Spanish to Mom and, of course, to Lita. She and Glenn, too, used nonverbal language as they bonded over cooking and eating, caring for family and laughing at funny mistakes, such as when Glenn purchased the wrong ingredients Lita had tried to tell him she needed.

In 1995, a few years after the birth of our baby brother, and when we had outgrown the gray family van, Glenn bought a bus. He had it turned into an RV and painted military green. One of our first destinations was the Black Hills of South Dakota to visit historic Mount Rushmore.

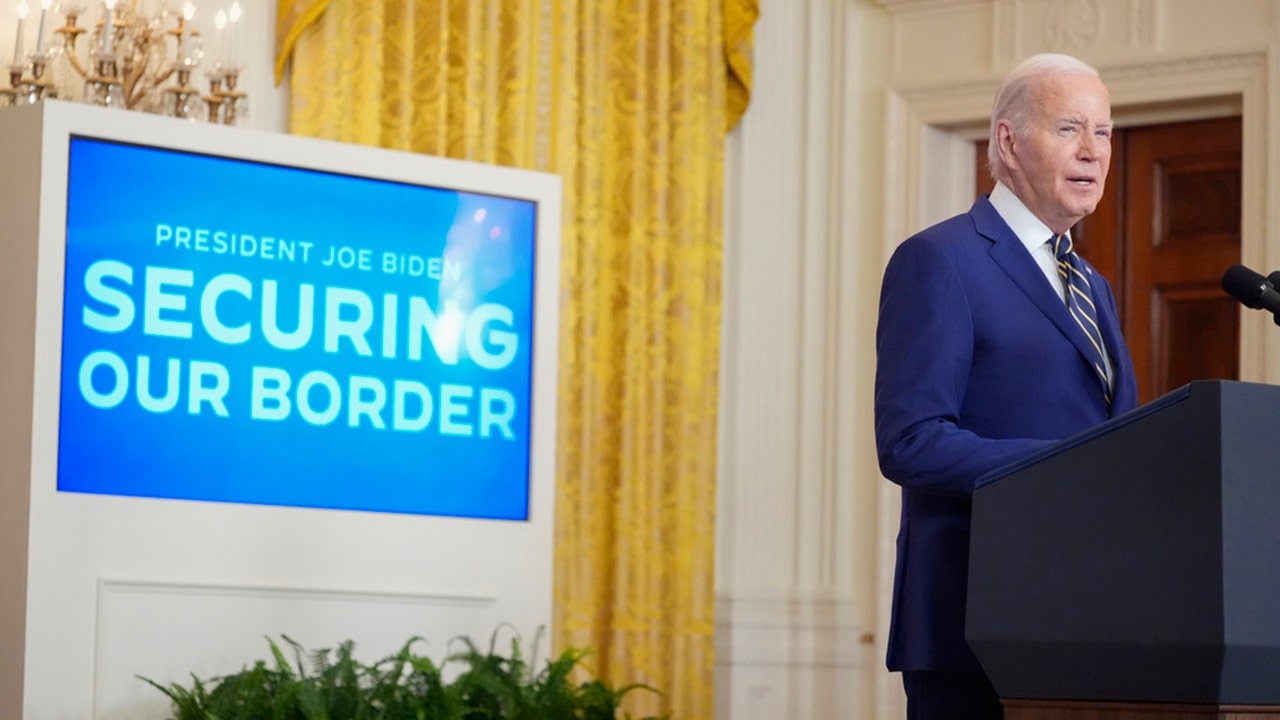

Glenn Hovde sits at the wheel of the “Patagonia,” a bus named for the place his mother-in-law threatened to move their large family became too much to manage.

Mom was initially against buying the bus, but Glenn insisted it was the only way we could travel comfortably as a family. We dubbed the bus “Patagonia,” a name inspired by the place Lita threatened to move to if we became too much to manage. We had the time of our lives on those bus trips — no small feat given that my sisters and I were tidy, girly and not outdoorsy.

Not that Glenn didn’t try to change that. He insisted we take golf lessons and go hunting. And he refused to cave to our squeamishness about creepy-crawly things. Once, when I spotted a bug in my bedroom and called for help, Glenn came to the rescue. He whacked the bug with a newspaper, making it bounce. He then popped it in his mouth, saying, “It tastes pretty good.” I screamed in horror and remained mad at him for days after learning that he had put a sunflower seed on the carpet simply to freak me out.

After an inchworm fell on Lita’s plate of eggs and bacon during a bus trip to upper Michigan, our camping days ended. But not our family time. Often, we gathered around the piano that had belonged to Glenn’s mom or played board games. When we performed modeling and dancing shows in the living room, our dad was always an enthusiastic audience, cheering and applauding.

Glenn always met our challenges with calm and encouragement. I arrived in the U.S. as a talkative fifth grader who loved to tell stories, but I became much quieter given my limited English. The first school my younger sister and I attended didn’t have a program for English as a second language. But thanks to the advocacy of a family friend, we were quickly transferred to a school with an excellent program.

It was reassuring when I won my school’s spelling bee less than a year after our arrival, going on to compete at the Madison All-City contest. Thanks to my mom’s influence, I was an avid reader but, of course, mostly in Spanish. Even after being elected high school class president for four years or accepted to my dream journalism school, nothing seemed to matter as much to Glenn as that spelling bee.

I think it was because he wanted us to feel at home. Glenn’s siblings and other relatives visited frequently as we were growing up. We five enthusiastic girls always joyfully welcomed them with open arms, which Glenn’s less demonstrative Norwegian family happily embraced. Glenn’s dad, Grandpa Inky, lived nearby and resided with us briefly, regaling us with stories about fishing, hunting and some of his near-death experiences.

For years, Glenn referred to himself as the family chauffeur, driving us to different schools and extracurricular activities. When we became citizens and were old enough to vote, he insisted we do so and that we stay updated on local news. For years, our family volunteered at Fourth of July community and fireworks events near our home.

My father will turn 80 this July 4, and he no longer believes, as his father told him when he was growing up, that the fireworks displays are to celebrate him. I am thankful to live close enough to visit him and Mom frequently in Madison. They continue to bask in the love and laughter of a larger family with spouses and grandchildren sit around the dining room table sharing stories in English, Spanish or Spanglish.

Of the many gifts my siblings and I have received from our father, I am most grateful for his sense of humor and how he uses it to teach us important life lessons. Moreover, I am thankful for his graciousness and patience as he helped integrate our families and cultures, welcoming cousins who lived with us for months at a time so they, too, could learn English. It never ceases to amaze me how our blended bicultural family came together, and how Glenn has never ceased to be the dependable, selfless father we can count on in times of joy and in times of need.

Mateus is a writer who lives in Fitchburg.