Wisconsin

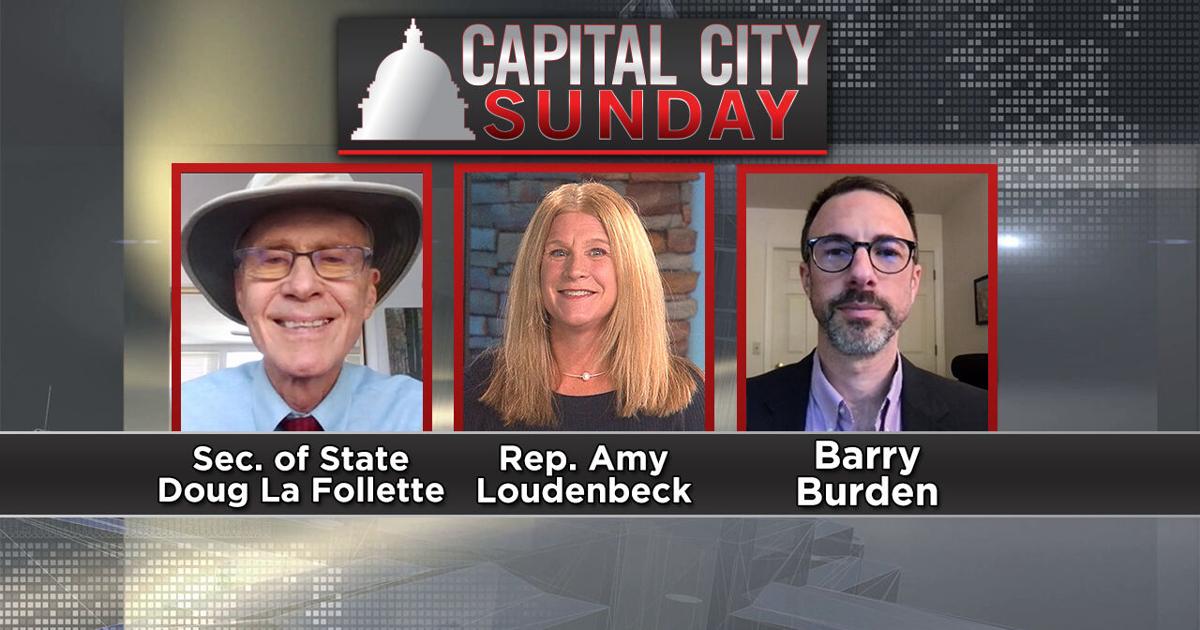

Capital City Sunday: What to make the secretary of state; what Wisconsin should know about direct democracy

We acknowledge you are trying to entry this web site from a rustic belonging to the European Financial Space (EEA) together with the EU which

enforces the Normal Information Safety Regulation (GDPR) and subsequently entry can’t be granted right now.

For any points, contact information@wkow.com or name 608-274-1234.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin chef shares tips to ensure your apples don’t go to waste

Laurel Burleson, a Dane County chef, thinks ugly apples make the best dishes.

One of her goals as a chef and restaurant owner is to save usable produce from the waste bin.

“I know how hard (Wisconsin farmers) work every day, making these products that are delicious and nutritious and for anything to get thrown away just because it’s not aesthetically perfect is just outrageous,” said Burleson, owner of Ugly Apple Cafe.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The latest fruit monitoring report from the University of Wisconsin-Madison shows many parts of the state having great harvests, although northeastern Wisconsin orchards suffered from a cool spring. But most apple orchards are busy with the fall harvest. So what do you do with that abundance of apples?

Burleson shared some recipes and her philosophy on cooking with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rob Ferrett: What do you like to do with apples apart from just eating them?

Laurel Burleson: One that I really like to do is making apple marmalade. That is shredding apples and preserving them in sugar so that they keep their structure. It’s kind of the opposite of making applesauce.

But we also make a lot of apple sauce and apple butter. That’s a good way to use a lot of apples all at once.

RF: What goes into making apple butter?

LB: Very basically you make applesauce, so just cook down your apples and blend them up. Then you take that applesauce and cook it extremely slowly, either in a slow cooker or in the oven. Cook it down until it’s dark and rich and more closely resembling a peanut butter than applesauce.

From there, you can put in whatever spices you want: cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, bay leaf. You just have to be careful because whatever you start with in the big batch will get super concentrated and reduced in your end product.

RF: With applesauce or apple butter, do we have to be fussy about the type of apples? Or can we mix and match?

LB: I like to mix and match, especially because the apple season starts really early. Some years you can get the first season apples in July.

They don’t hold very long and they’re very juicy, so they break down really easily, but they are very tart. I like to get some of those early season apples and make them into applesauce and freeze them and then when I have other sweeter varieties later I mix them and then reduce that all down into butter.

RF: You shared a savory recipe with us for pork chops with apple bacon cabbage. Tell us a little bit about this recipe.

LB: It’s really fun for the fall and even into the winter. You can kind of use any kind of variety of apple that’s a little bit tart and it’s OK if it breaks down and blends in because the cabbage is going to maintain its structure.

If the onions and apples melt away into a delicious sauce it’s just fine. But also, if you end up with some apple pieces, then it’s a nice little surprise like a little sweetness.

The Ugly Apple Cafe operates cafes inside the Dane County Courthouse and the City County Building in Madison and sells its products at the Monona Farmers Market.

Wisconsin

Former Wisconsin transfer scores 43-yard touchdown in Indiana’s big win over Illinois

While the Wisconsin Badgers struggle on the football field, sitting at a disappointing 2-2 through four weeks, some of the program’s former transfers continue to find success.

One of those players is tight end Riley Nowakowski, who transferred to Indiana this offseason after five years with the Badgers. The Milwaukee, Wisconsin, native originally walked on to the program as an unranked outside linebacker. After playing sparingly during his first few seasons with the Badgers, he flipped over to fullback in 2022, then out to tight end after Phil Longo arrived in 2023. Nowakowski totaled 18 receptions for 131 yards and a touchdown from 2023-24; his two years as a primary offensive contributor.

The former Badger is already making significant progress toward those totals, now just four games into his Indiana career. He has four catches for 72 yards and a touchdown, plus one carry for a one-yard score. The versatile fullback/tight end delivered the highlight play of his career during Indiana’s blowout win over Illinois on Saturday, taking a 1st-down screen pass 43 yards to the house.

Wisconsin, meanwhile, has received solid contributions from Montana State transfer tight end Lance Mason. The veteran has 14 catches for 177 yards and two touchdowns to date, leading the team in each of those respective categories.

While Mason has been one of the Badgers’ few bright spots through four weeks, it’s hard to ignore Nowakowski’s emergence as one of Indiana’s dependable offensive playmakers.

Contact/Follow @TheBadgersWire on X (formerly Twitter) and like our page on Facebook to follow ongoing coverage of Wisconsin Badgers news, notes and opinion

Wisconsin

Southeast Wisconsin weather: Dry Today, Warm Workweek Ahead

Get ready for an overall warmer stretch of weather as we head into this upcoming workweek. After some fog lifts this morning, we’ll have plenty of sunshine today with highs in the mid to upper 70s along the lake and low 80s inland.

Tonight will be dry with lows in the low 60s lakeside and upper 50s inland.

Monday through Wednesday should be very similar, with upper 70s to near 80 near the lake and low to mid 80s inland with plenty of sun.

We’ll start to bring in chances of showers or a T’storm starting Thursday right on into the weekend.

WATCH: Southeast Wisconsin weather: Dry Today, Warm Workweek Ahead

Southeast Wisconsin weather: Dry Today, Warm Workweek Ahead

TODAY: Any fog lifting through the morning, then becoming mostly sunny.

High: 77 lakefront… 83 inland.

Wind: E 5-10 MPH.

TONIGHT: Mostly clear.

Low: 62.

Wind: ESE 3-8 MPH.

MONDAY: Mostly sunny.

Highs: 78 lakefront… 83 inland.

Wind: ESE 5-10 MPH.

TUES: Mostly sunny and warm.

High: 80 lakefront… 84 inland.

WEDS: Mostly sunny and warm.

High: 81 lakefront… 85 inland.

THUR: Partly cloudy with a chance of a shower

or T’storm.

High: 80.

It’s about time to watch on your time. Stream local news and weather 24/7 by searching for “TMJ4” on your device.

Available for download on Roku, Apple TV, Amazon Fire TV, and more.

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoReimagining Finance: Derek Kudsee on Coda’s AI-Powered Future

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSyria’s new president takes center stage at UNGA as concerns linger over terrorist past

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThese earbuds include a tiny wired microphone you can hold

-

North Dakota1 week ago

Board approves Brent Sanford as new ‘commissioner’ of North Dakota University System

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTest Your Memory of These Classic Books for Young Readers

-

Crypto1 week ago

Crypto1 week agoTexas brothers charged in cryptocurrency kidnapping, robbery in MN

-

Crypto1 week ago

Crypto1 week agoEU Enforcers Arrest 5 Over €100M Cryptocurrency Scam – Law360

-

Rhode Island1 week ago

Rhode Island1 week agoThe Ocean State’s Bond With Robert Redford